EDITOR’S NOTE:

RevolverGuy is exceptionally proud to present Mr. Mike Hipple, and his firsthand account of the first Leatherslap contest.

Serious RevolverGuys know the Leatherslap as a significant waypoint in the journey of combat handgun training and competition. Some would describe it as the post-war origin of the effort, and shooting great Elden Carl would describe it as, “arguably modern combat pistol shooting’s most famous event.” Subsequent Leatherslap competitions would eventually morph into the Southwest Combat Pistol League (later, the South West Pistol League) and International Practical Shooting Confederation, and introduce the shooting world to influential pioneers like Carl, Jack Weaver, John Plahn, Thell Reed, and Ray Chapman, among others.

It’s unquestionable that the Leatherslap’s founder, Lt. Col. Jeff Cooper, had a disproportionate effect on the trajectory of combat handgun training and competition. While Cooper didn’t “invent” or “discover” all the components of what would eventually become the Modern Technique of the Pistol, he did assemble and codify them as the Modern Technique, and shared them with the world through his writing and his schools.

So, the story of the first Leatherslap is important history for RevolverGuys, and a detailed report from one of its participants is invaluable. I was excited to receive it from Mr. Hipple, but after reading his manuscript for the first time, I realized his story was important for reasons well beyond the historical aspects, because his is also a story about values, camaraderie, friendship, mentors, honor, leadership, responsibility, respect, inner strength, and the road to maturity. These elements resonated with me in a way that very few authors can achieve, and I know you’ll feel the same way, because he’s one of us. His values are our values, and his story is also our story, in many ways.

It’s a beautiful tale, and perhaps the best story to grace these pages, yet. I’m especially proud and grateful that he shared it with us. I know you’ll enjoy and appreciate it as much as I did.

-Mike Wood, Senior Editor, RevolverGuy.com

*****

AUTHOR’S NOTE:

I need to explain something here. This was 1956, which was just ten years after the most inhuman, unbelieveably brutal world struggle in written history. Every adult you would encounter had been living through the terror of horrific world war for years. There was no confusion about the right of arms and every adult I met in the gun world found it just second-nature to look after the youngsters. No one coddled me that day, but everyone on that hill made sure I felt welcome to this table. This was the America I first opened my eyes to and this is the America I salute when I hear Taps for the last time.

-M.C. Hipple

*****

In the spring of 1956, I was 16 years old, in high school, and living with my folks in Burbank, California. Dwight Eisenhower was the president of the United States, Morris Poulson was the mayor of Los Angeles, Bill Parker was chief of the LAPD, and Gerald Goldberg was my friend. At this point in my life, the most beautiful things I had ever laid my eyes on were Annette Funicello and any Colt Single Action Army revolver.

Gerald was about a year and a half older than me and a fellow gun enthusiast. We had witnessed the rise of the awesome birth of the Arvo Ojala holster and the incredible wave of popularity the concept of quick-draw science was having in the media. At the time this all began, I was making do with my three-screw Ruger Single Six and a rig I threw together with an army web belt and a Nudie’s holster. I had never fired a live round from a combat stance in my life. This was strictly a Hollywood path.

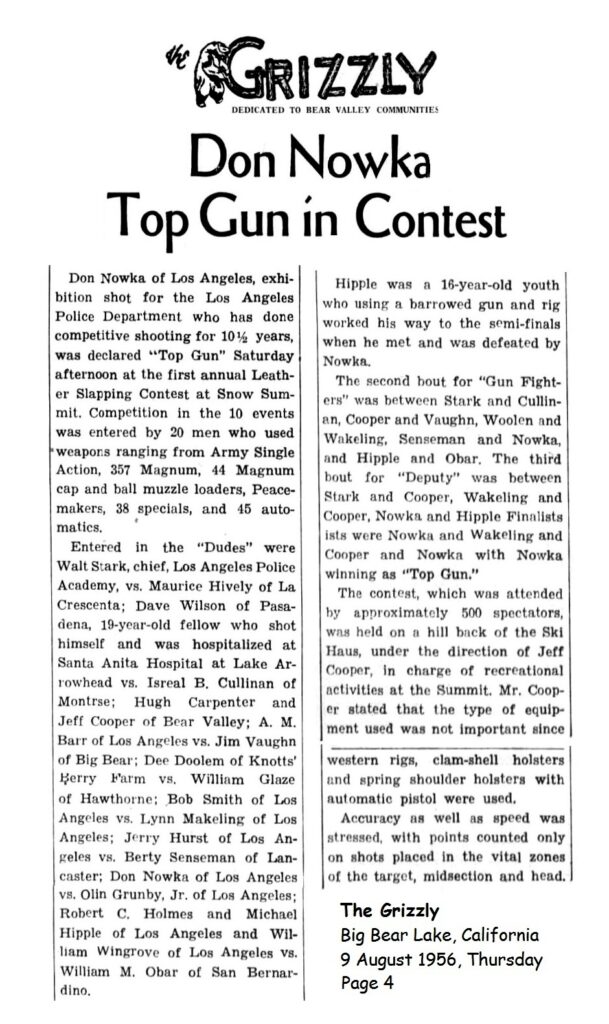

Gerald’s mischievous obsession with adventure would change all that when he encountered a poster that was promoting a pistol competition as part of the annual “Miners’ Days” festival in Big Bear, California. The big print said it was “The First Big Bear Miners’ Day Leatherslap contest” and the smaller print noted only factory ammunition would be acceptable for the shoot.

He couldn’t wait to show it to me. The document declared entitlement to anyone who showed up with a functioning pistol of power equal to .38 Special or above, a serviceable holster or rig, a ten-dollar bill, and age-verification of 16 years. There was not a whiff, a speck, a hint, or even a whisper of Hollywood in the flyer. There were no stipulations as to historical authenticity of the guns. Nor were there limitations on the rig of choice other than the gun had to be housed in something other than a pocket. Ten dollars would buy a chance at a hundred-dollar pot in a live-ammo shoot. The event was magically real. Gerry and I thought it was possible there had not been a shoot like this in the past 50 years; Or ever, for that matter!

I was hesitant. Gerald persisted. I had no gun. A gun and ammo would be provided on trust. Big Bear was a hundred miles across the Mojave from Burbank. No problem, Gerry had a Buick V8 convertible. I had no gun. Don’t worry. And so it went, every week, until we gassed up the Buick.

THE JOURNEY BEGINS

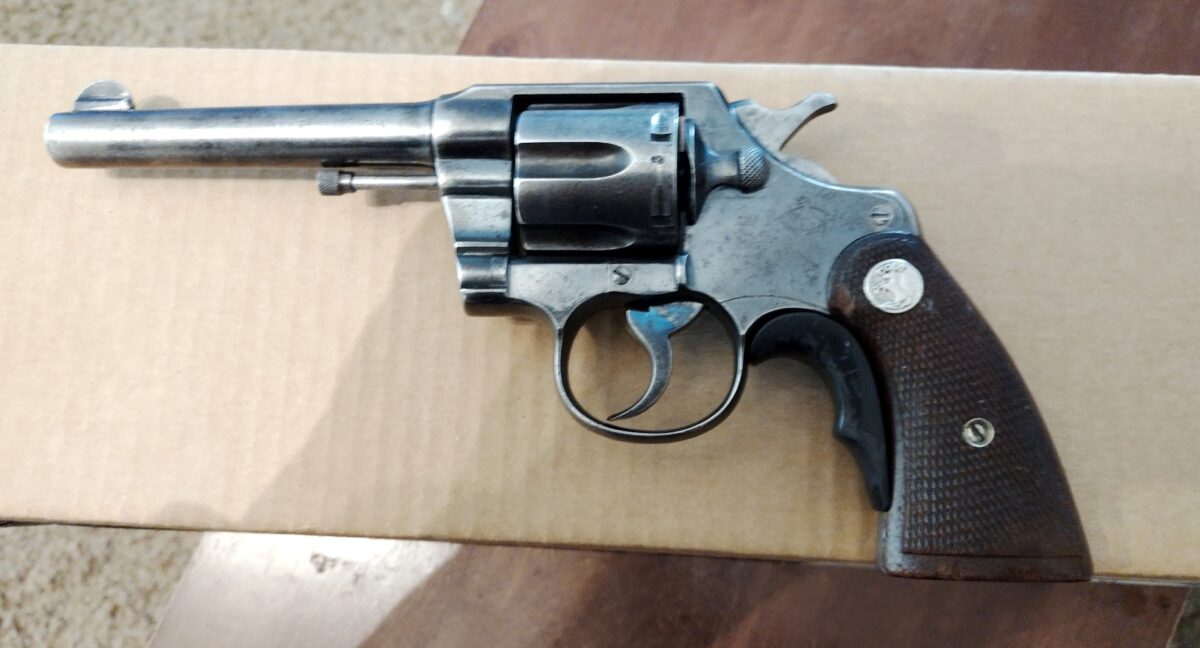

I met the Colt Army Special when we were on the way to Big Bear. We were on the road before sunup and Gerry pulled off the desert road right after dawn so I could check out the pistol. This was supposedly the smart thing to do but the real reason was to avoid public embarrassment in the presence of seasoned shooters (i.e., any grownups who could, might, or by any stroke of destiny, actually meet my mom and dad). The only good thing that came out of this orientation was losing the worry that I might shoot myself in the foot.

The lock work was tight and the gun was chambered in .38 special. The double action trigger pull, however, was proof that God does indeed have a sense of humor. Let me be clear. I was sixteen years old and weighed 140 pounds with rocks in my pocket. The Army Special lock work is a direct copy of the big Colt New Service .45s. To this day, I don’t know how I dragged that trigger for shot after shot during that match.

My brain raced as I loaded the big handgun. The whole idea was blood real, especially for a novice like me. This would not be blanks, or wax bullets. The match flyer had reached a hundred miles westward to the San Fernando Valley and God knows where else, or how far. It was the uniqueness of it, the rare animal blood challenge of it, that demanded respect. I didn’t know it then, but there would be other similar challenges in my future and every time I said, “Yes,” it was the, “Yes” of that morning, in that spot of the Mojave Desert. And the voice of it, every time, right up to this day, was the sound of the first round from the muzzle of that pistol.

We put up a can in a greasewood bush and I drew and fired six times. Parts of the bush were a little shorter, but the can never moved. Gerry held out the box of .38s but I just shook my head and told him to save it. He didn’t argue; It was clear that twenty more minutes of practice wouldn’t make the braids on this girl any longer. We would have ninety-four rounds for the shoot. Apprehensive or not, there would be no backing out. I was committed to playing out the hand.

About an hour later we were standing in front of the sign-up table and I was looking at Jeff Cooper and company for the first time.

THE MATCH SETUP

I submitted my gear for inspection at the table and handed over my sacred ten-dollar bill to an old timer with a tin box. My youthful appearance drew notice, but if Cooper was concerned, he didn’t show it in his critique. He had a forward-biased tone for explaining the standard range requirements and the match process. His voice put me instantly at ease and I felt a great deal of compassion coming from my fellow shooters and the match support judges and volunteers that were gathered around. In a few short years I would associate the natural calm in his manner with leadership, and there would be other faces to go with this voice.

The shooting would take place at the bottom of a hill adjacent to the summit lodge. A flat patch had been cut out of the hill and two posts had been erected seven yards in from the shooter line. Full-size, FBI-style, black silhouette targets were attached to each post. Then, at the beginning of each shoot-off, an inflated 12” balloon would be attached to the target to represent the “vitals.”

Shooter pairs would align side-by-side on a line in the ground and ready their sidearms. Each shooter had an assigned judge to supervise their actions and there was a third judge stationed between the combatants to call the hits. This guy would also signal the “draw” with a police whistle. The first shooter to break his balloon won the bout. A shooter had to win three bouts before his opponent to win the event and go forward up the ladder. You can see that with this system there would be no ties, but there would be room for “inconclusive”–a phrase that meant, “Do it again!”

The array of sidearms and rigs was unbelievable. Colt and Smith double actions were dominant, but there was a notable cowboy single action presence, also. Gerry said he saw one guy with a 1911 and at least one cap-and-ball thumb buster, but I don’t think they were in the match. I saw at least one Luger and a Broomhandle Mauser 96, and Gerald noted some guy with a Bergman-Bayard! Rigs represented included a few Hunter practical models, to drop loop western styles, to modern quick-draw rigs, to spring-actuated clamshells, and standard and spring-clip shoulder rigs. Very little costume clothing was in the match.

Although there were a few outdoor-style picnic tables with benches scattered around the parking lot between the lodge and the shooting arena, there was no place to sit other than around the signup area. Someone on the volunteer team had the compassion to see to a few galvanized tubs with iced down soda pop and beer. The sun was up and hot, and the call for shooters went out. Gerald peeled off to the spectator area with the other support folks, and I joined the shooter pool.

There is so much of this I cannot remember clearly at all, and some things I just never forgot. Everything started and stopped by the judges. They would confer and then call a pair of shooters. Each combatant would take his place and load his sidearm, and then signal the judges he was ready. There was a distance requirement for the gun hand but I don’t remember what it was in inches. Nobody had a ruler there, anyway. Courtesy was the sovereign coin of the day. At the whistle, you did your best to break your balloon before the other guy, and judgement was eyes and ears. In order to win, you had to really, really win. It became a very long day.

NEAR TRAGEDY

This was especially true for Dave Wilson, who shot himself in the leg in his first bout. A spectator crowd from other Miners’ Days events had begun to gather, and without seating, the vision plane was “two pairs of shoulders.” Gerald brought the word and said a ham radio message went out, and an ambulance was on its way. Meanwhile, Dave was laid out on one of the picnic tables with a couple of volunteers for company. The match continued.

Dave was using a single-action but I don’t think anyone knows what happened except the judges. Total tragedy was avoided by the EMT crew, but everyone felt sorry for Dave’s bad luck. I reflected that if I’d have done that, my pop would revoke my gun privileges until I was in my thirties.

SHOOTING THE MATCH

On the record, I was first paired with Bob Holms. I don’t remember much at all about Bob but I did not stumble getting into position and I didn’t drop my gun when loading up. Thusly, memory lays naked my process of being for those moments. I was deathly self-conscious about how green I was. Without training, I shot without style of any kind; Just a yank and shoot right out of the leather. I scored three out of three, and won my first event. When I cleared my brass one of the judges patted me on the shoulder and said, “Good shooting, kid.” I don’t remember any effect at all over my winning shot, but the friendship in that man’s voice sticks with me sixty-seven years later.

It was clear that I was very quick. But there was no way around the trigger pull; I simply couldn’t maintain control of any kind for more than three shots. I left the first event with a vengeance commitment to three-shot strings the rest of the match. The sun was hot, there was precious little shade, and the gunfire had attracted about a hundred spectators by this time. Gerald had found us some cold soda pop. I was building a really nice, “You got me into this!” grudge, but swallowed it with the first pull of that A&W. The hot sun, the sweat, the noise, and the aches and pains would become a familiar zone for me, for the rest of my life. I would have many first-times in my life, and being the new kid would become a trademark.

Bill Obar and I shot it out four times. My three-shot strings proved handy because the inertia landed the third shot for me. But I lost some control and that cost me a target on one round. It was troublesome, but again, there was a “Good shooting, kid” endorsement, and I brushed off the worry and stepped away to a crowd of several hundred spectators. At this point, the only people who could see anything but each other were the shooters and the judges. The Leatherslap was a success.

I squirmed close enough to the action to see a little of what’s going on, and Gerald joined me for company, when one of the shooters, a single-action guy, had a problem getting out of the leather. His opponent killed his balloon a full second before our guy, and he was so absorbed in his struggle to get off a shot, that, with industrial-grade frustration, he fanned-off six rounds machinegun-fast way after the bell. The crowd went completely silent for about 10 seconds, and then from the back came, “Is he dead, Mr. Dillon?” I’m sure that people all the way in San Bernardino wondered what the fun was all about.

THE FINAL SHOWDOWN

The laughter shattered the tension and I was feeling pretty good when I stepped up to the plate with Don Nowka. Maybe I should have hung onto my tight competition grip, but I don’t believe now, and I did not believe then, that it would have made a difference. Don was a trained gunman, and a better shot. Determination can get you pretty far down the road, but you gotta know how to drive, if you want to finish first. We shot it out six times. Two for Don, two for me, one inconclusive, and the final kill shot for Don. And, again, there was the friendly nudge from the judges after I cleared my brass.

Gerry and I stepped to the edge of the crowd to get some breathing room and take an attitude check. The next day, the Big Bear Grizzly newspaper would claim a crowd of 500 people attended the shooting event. Speculation was that the gunfire lured them away from other events. I don’t think anyone in that gathering considered they had witnessed a small part of history. I know Gerald and I didn’t.

GOING HOME

It was late in the day and we were more than a hundred miles from home. We beat the crowd out of the parking lot and headed down hill toward the Mojave, and the San Fernando Valley beyond. This was years before standard air conditioning in cars, and we put the top down. We were both jazzed but the post-game downer settled in after a half-hour on the road, and our conversation dragged to a stop most of the way home. My mind spent most of the drive wondering what mom was planning for dinner and what part of this day my dad might find interesting. When Gerald dropped me at my house the rig went with me and the gun went with Gerald.

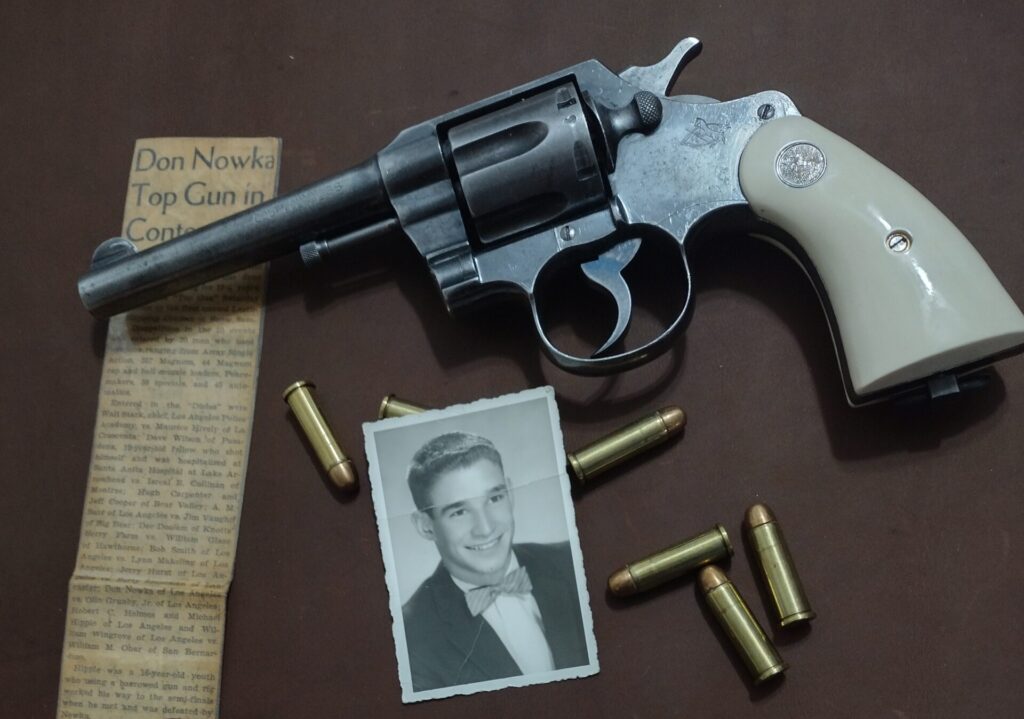

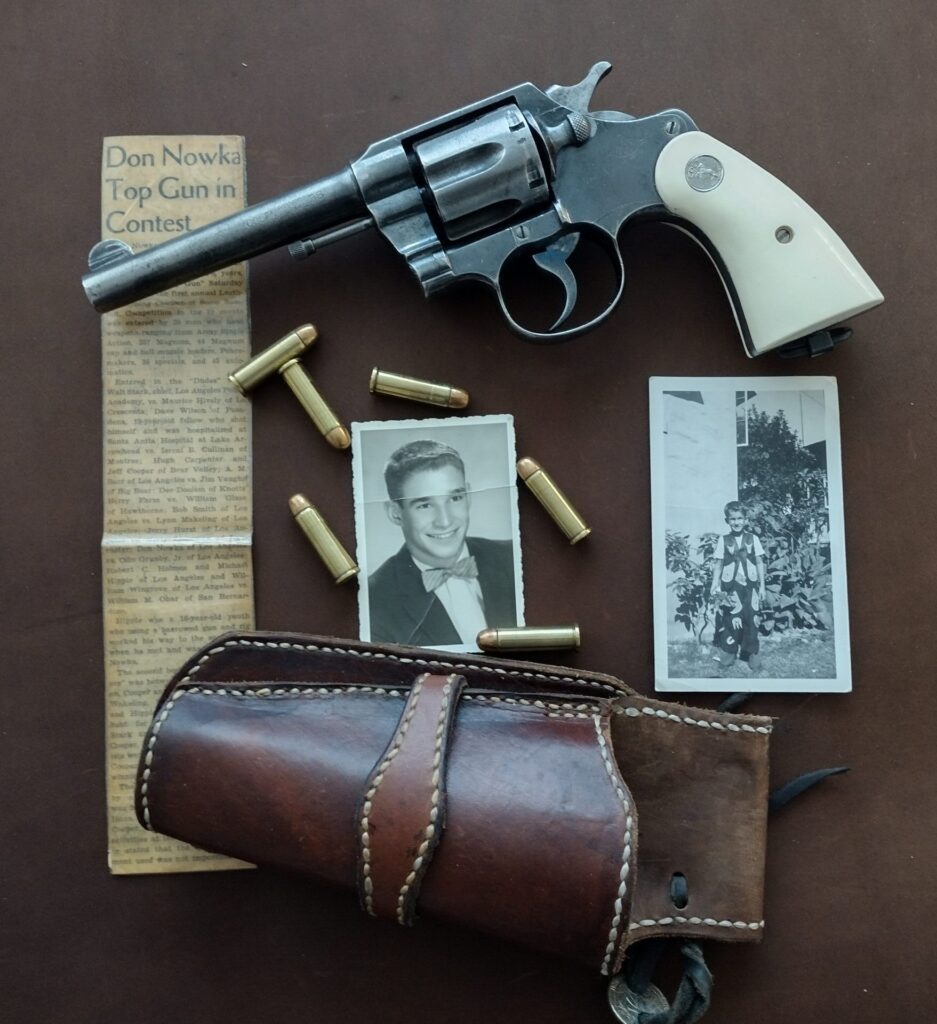

A few weeks later, Gerald scored two copies of The Grizzly that covered the Leatherslap. My mom actually cut out the article and laminated it. Four years after the shoot, I joined the army. A year later, Gerald was drafted. We hung out together for a while after our discharges but by that time, we both were married with kids on the way.

THE LAST VOICE I HEAR

By the end of 1965 we lost track of each other for the next fifty years. Thanks to my wife, I went looking for him in 2014 and we collided on Facebook!

Eventually, I took a Greyhound to Arizona to visit Gerry and his wife, Ellie for a few days. When we had enough time to settle in, I pulled out the old, yellowed clipping encased in plastic for over two generations. I wanted him to have it to put with the old Army Special. He was very touched and excited and said he would mount the pair together when he dug it up. The move to Arizona had been hectic.

The following year his brother died and while Gerald was in California, he gave me the gun. He wanted me to have it. He always felt the gun and I belonged together after the shoot, and hung onto it all these years. We stayed in touch by phone several nights a week until he died in March of 2020. Ellie had died a few months before.

Throughout the two years leading up to his passing, I would bring up the subject of heart surgery and he would change the subject. His main fear was that Ellie would be helpless if things went wrong with his operation. His other concern was the future for his daughter, Denise. He was very successful with both. Ellie had his and her daughter’s company in her last moments, and Denise inherited a decent estate. Gerald died on the table.

There were so many hours of conversation that I can still recall a little of Gerry’s voice, but by the time my granddaughter is in the third grade, it will probably have faded to become company to all the voices we mingled with on that hill, a lifetime ago. But when I take that old chunk of steel with the faded blue job, and the perfect lockup, to the bench and unleash hell at a poor piece of paper that was just minding its own business in a rack, I see that wicked, mischievous smile that showed me a flyer over a half-century ago, and I think, “Good shooting, Kid.”

*****

lead image:

The Colt Army Special used by Mike was made in the first year of manufacture, 1908. When Mike first shot it in 1956, it was in stock configuration, with Colt gutta percha grips. When Mike’s friend Gerald gave him the gun decades later, it was outfitted as shown, with walnut service stocks and a grip adapter. Mike says, “the grip adapter would have been a big help in 1956,” but it sounds like he did plenty fine without it!

A great slice of history and writing that takes me to a time and a place.

Well done Sir! An outstanding account of the hobbies early days and a poignant description of friendship. Who among has not experienced those butterflies being “on stage”, it’s tough.

Thank you and God bless you.

This story instantly brought back to me mid-50s Southern California. Up until the early 60s, I recall witnessing fast-draw, single-action revolver competitors (using blanks, of course) demonstrating their speed in front of the old Gemco store in Fullerton (Orange County, California). Jeez, if that happened today, there might be weeks of college campus unrest.

It takes a lot of work NOT to be friends with someone you shoot with.

What a great story! How cool to have shot in that particular match on that particular day! You and Gerry doing that as teenagers in California just makes me smile. My first centerfire handgun was a Colt Army Special that I bought in a pawn shop as a sophomore in high school, it had a similar trigger. It makes me appreciate how well you did that day- a very respectable showing in front of a bunch of grown men and Jeff Cooper, to boot! Thank you for sharing it, Mr. Hipple.

I want to thank Mike again for his story, and also want to recognize the work of two men who helped to bring it to light.

Gunsite historian Jay Hohenhaus (RIP) and law enforcement historian Craig Smith teamed up to find Mike and get his story and photos on record, and we can’t thank them enough for their efforts.

After considerable effort, Jay located Mike and arranged for him to be interviewed by the Gunsite staff for their upcoming anniversary coverage. Jay had plans to work with Mike on other projects, including the publishing of this story, before Jay’s untimely passing interrupted them.

In tribute to his friend Jay and his excellent work, Craig stepped in to help Mike find an audience for his story after Jay’s passing. He contacted me and put the two Mikes together. Besides introducing us, Craig provided other valuable assistance to the project. He obtained images from Mike, and cleaned them up for publication, and also recreated the original Grizzly newspaper report so you could enjoy it, as the reader.

Readers generally don’t get to see all the sausage making that goes on behind the scenes to create the stories they see here at RevolverGuy, but I can guarantee that each one of them is a collaborative effort by friends. I didn’t want to interrupt Mike’s telling of his story more than I already did, so that’s why I’m sharing this in the Comments, but I did want you to know about the folks who helped on this one, because it was a special effort from a group of guys who didn’t want this special story to get left behind.

Although I never had the honor of meeting him, I think Jay would have been very pleased to see how it all turned out. De Oppresso Liber!

Outstanding to see this in the light of day! Now, if we could only get younger shooters today to actually be interested in the history of how we got where we are, things might be better in the industry. The term “living history” applies here.

Roy Huntington

I know that’s one of your forte’s Roy. Glad we could make a contribution to the effort.

Amen!

Really outstanding story! For me, stories like this are the foundation for what “gun culture” means to a lot of us. Early exposure to firearms and support from people that would encourage a continued participation in shooting sports and using firearms for practical purposes is a foundation that so many people misunderstand. Thank you for bringing this story to us!

Amen, Mark. You nailed it.

Well written! Which is not to be taken for granted. Good work, Mike, on publishing this.

Thank you Sir! Mr. Hipple deserves all the credit, though.

I bet you spied the references to the Nudie’s, Hunter, and Ojala holsters right away!

That was a great story. I love reading the origins of “combat shooting” and how it evolved. He was there at the start. The birth.

And as the owner of a Colt Army Special (in .32-20), I have to say how impressed I am with his performance. To have first seen the gun on the way to the Leatherslap? I bow to you, sir.

Excellent article! I can’t wait for the follow up!

Outstanding !! (Yeah, I know, it’s verbose and repetitive). Mr. Hipple’s account exemplifies a treasure that such an experience can be, and what has been lost on the post baby boomer generation. As Spencer pointed out, if that event went down today, between the Karen protestors and the media, the destruction would be beyond digestion. The youngsters want everything now, and do not generally want to share the way Mr. Hipple shared leather and revolver. They can’t pick up an early 1900s Colt Army Special and envision the history the gun had seen.

Growing up in 1950s-1960s central Florida, there were no such events like Leatherslap that us young and budding gunslingers could attend, much less have someone to mentor us. I was fortunate in a way to have had a sergeant with the Orlando PD (at the behest of my late mother) take me under his ‘wing’ and teach me how not to shoot myself in the foot, or leg, or anyone else. The first gun I actually got to fire was his Ruger Blackhawk .357 with department wadcutters. It was a kick in the pants for me and instantly addictive. My maternal grandparents lived in Maine, and g’pa had a collection of British weapons. Over one summer before Khrushchev put missiles in Cuba, he introduced me to his Webley in .38-200, and in .455. I had hit the big time. He had friends in the state police that would conveniently show up from time to time and let me try out things (obviously pre planned, but who cared ).

Meanwhile, back in Orlando, I would periodically get to shoot some real police revolvers, specifically the Colt Trooper and the S&W Model 15. I felt like I was getting to the big time.

All that came to an end in the late 1960s when Uncle Sugar invited me to stand on those yeller footprints.

While I never had any lifelong friends like Mr. Hipple, I came to appreciate that value of someone trusting this kid with a loaded firearm, and actually being able to treat it with deference and respect. As I got into law enforcement and equipment began to change, I did manage to get one of the Orlando P.D. ‘border patrol’ style holsters that I remembered as a child. That and a Model 15-3 will have to be my memory of slapping leather.

Mr. Hipple – THANK YOU for sharing this with us all . . .

I just love how a great story pulls more great stories into the light! Sounds like Mom and Grandpa did a great job of making sure you were exposed to firearms and the proper instruction in handling them. Now I know where your fondness of the .357 Blackhawk started!

Jay’s wife sent a thank you in appreciation for the recognition of Jay’s work.

This was a two year plus project for both of us!

Thank you to Mike Wood from me for everything he did bringing us home.

It was my honor to be a small part of it, Sir! Thanks for all the effort. I know this story will reach well beyond the RevolverGuy audience.

What a cool story!

I particularly liked the “eyes and ears” scoring method. Kind of a long way from what’s used today.

Being more of a Smith guy, I’d never heard of the Colt Army Special. So besides telling a fun and interesting story, Mr.Hipple taught me some firearm history. Thank you.

Wow, what a great story! Thanks! Jay was a good man and gone much too early.

I so enjoyed Mike’s article for various reasons: Mike and I are of the same age…old! I was also 16 in 1956, don’t like to count how many intervening years have passed. I also grew up in Southern California and took many trips to Big Bear in the San Bernardino Mountains.

The Leatherslap contest really caught my attention. Much like Mike I was enthused about the fast-draw craze in SoCal at the time. I attended Paramount High School and I remember vividly an assembly of the whole student body in the school gym. Thell Reed put on a fast-draw exhibition for the assembly, shooting blanks and hitting weighted balloons released from his shooting hand before the draw. I had never seen a draw so fast.

Just imagine such an exhibition at a school today. Everyone would wind up in jail!

Fantastic, Dick! That must have been a sight to see.

It was quite a sight Mike! I have reflected on that exhibition frequently, comparing the political environment of the 1950’s that allowed such a display of “gunman-ship” at a public high school to the politics of today that wouldn’t even consider such an exhibition. Sad times we live in!

Mike Hipple has a story about Arvo Ojala giving an impromptu demonstration in a gun store range to him and another teen friend. Both were dazzled.

Mike is working on more remembrances that I hope we can share here soon.

Wow! What a wonderful telling of the time when Leatherslap happened! I’m glad it’s preserved here, right where it belongs!

We’re lucky Mike shared it with us all!

This story made me go back to 1957 in my mind. I was having a 9th birthday coming up, in a couple months. One Saturday morning my dad said come on son, go with me. I got in the car, and he took me to Mt Sterling Ky, and we parked on the street across for a Pool Room on the corner of Locust/Maysville Street. We got out and dad and I went across the street and into the Pool Room. Dad ordered him a beer and me an Ale 8 soda pop. Behind the counter/bar was a big mirror and it had long guns all across the front of it. Turned out the establishment sold used long guns.

To my surprise my dad asked the man to see a couple long guns. They were 410 Ga and single shot breakdowns with hammers one had to cock. One was very long, and the other was shorter. It was a Stephens break down single shot that took both 2 3/4 and 3″ shells. It looked new. He asked me which one I wanted kind of in private. I told him the Stephens. He asked the man what he wanted for the guns. They haggled for the longer gun then dad all of a sudden told the guy he like the long one, but would give him 20.00 for the shorter Stephens. The owner thought for a minute then said “Ok” so dad took a 20.00 out of his billfold and paid the man. The owner was asking 35.00 for the Stephens and it amazed me why dad did the flop on the dicker for prices.

We finished our drinks and we left with the little Stephens. I was totally surprised. Here I was 8 years old with my first and own hunting gun for my 9th birthday. We then went to Western Auto and purchased a box of number 6 shot shells for the Stephens.

Later that day, I asked dad why he haggled the way he did, and he told me he wanted the owner to think he wanted the longer gun, so the owner was holding the price up. By making a quick offer on the shorter one the owner would cut to the bear-minimum, on the shorter one. That was one way how one could haggle for the best price. Anyways, it worked.

I am 76 now and am giving my grandkids all of my gun collection so my wife or family will not need to get rid of them after I don’t need them anymore. I gave the little Stephens to my youngest grandboy who lives in S Carolina. Got a movie of him hunting squirrels with the 410, last fall, and his dad said he loved the Stephens. “It totally warmed my heart” to witness the fun Parker was having shooting squirrels with the 410.

Thanks for the great story of the first Leatherslap. Great story Mike.

Pop Pop, it’s GREAT to hear from you again, and I REALLY enjoyed the story! What a neat memory of how you got your first gun! The times sure were different back then, weren’t they?

I’m glad you enjoyed Mike’s story so much, and that it triggered such a fond memory for you. Now we all get to enjoy your story, too. That’s a win-win for all of us.

It makes me smile to think of your grandson carrying your gun afield. What a super tradition to pass on. Your dad is smiling too, I bet.

A great story of a great time. History like this needs to be recorded, thanks

This site has kindled a love for revolvers for me…but this story was absolutely heartwarming for me. I am only getting into guns as of the past few years, but stories like this make me value the history of strong and sharp men such as Mike here. Despite being a millennial, I find the wisdom of the older generations to still hold value. This was absolutely wholesome!