One thing all firearms have in common is the need to be fed if you have a desire to enjoy them to their full potential. If you have more money than you know what to do with, then you can comfortably order ammunition on line – assuming it’s even available, as witnessed by this year’s run on munitions of nearly every caliber. For the rest of us, there is either the choice to shoot less, or reload your own.

Editor’s Note: I’d like to welcome my very knowledgeable friend, and long-time RevolverGuy reader, Stuart Bond to our pages as a writer. I was excited when he volunteered to write this article about reloading, and hope we’ll be able to twist his arm into doing more articles here, because Stuart is one of those guys who really knows his stuff! -Mike

If you are new to the notion of reloading your own ammunition, before you even think of spending any money on equipment or components, get a good reloading manual. Get several manuals, such as from Speer, Hornady, Sierra, Nosler, as well as the powder manufacturers. Hodgdon and Alliant are the two major powder suppliers in the U.S. VihtaVouri is an excellent powder from Finland, and is most definitely worth consideration. All suppliers publish load data for their powders for more cartridges than one can imagine.

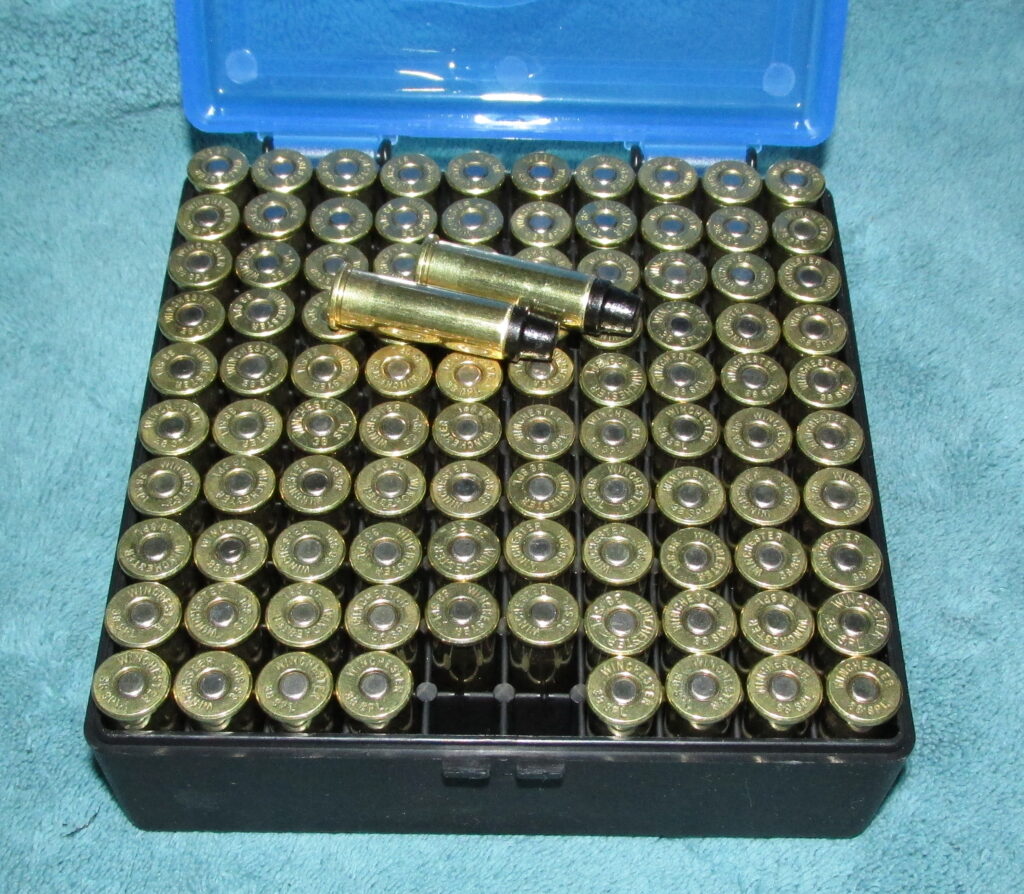

Study each one of these manuals, as well as the online loading data provided by the powder manufacturers, and see how variations of components and powders might affect your decisions. For those who might be new to shooting, unfamiliar, or even unsure about what all is involved with the process of reloading your own ammunition, let us start with a process and component overview. The essential steps to reloading any cartridge involves having all your components at hand: empty brass, a sufficient number of primers, gunpowder, and bullets.

Before I start, I need to make a disclaimer. I will mention and even recommend certain products or brands by name. I get no remuneration from any manufacturer, supplier, or distributor. My recommendations are based on my experience of reloading my own ammo for the last (almost) 50 years. I have used nearly every loading tool, powder, and other components along the way, and have come to appreciate superior product performance when I find it.

Having stated this, a good place to start is Midway USA (formerly Midway Shooter’s Supply). I have ordered product from them for the last 30 years and have always had excellent customer service. Do a search for reloading components, and you’ll find a seemingly endless list of choices in bullets, primers, powdered, and even unprimed new brass. The Midway site will let you see what loading manuals are available, as well as give a visual frame of reference to what components look like. Keep in mind that in the current political climate, most ammunition and many of the components are pretty much wiped out. What is available is usually going for prices that one expects during a crisis. Many of us stocked up over the past three years because the proverbial political handwriting was already on the wall.

BRASS

Cartridge brass is the one element that requires the most attention and preparation. Some folks are not particularly choosy about the headstamps on their brass, while others, such as myself, can be downright snobbish. Personally, I sort all brass for a given cartridge by headstamp. I also separate nickel-plated cases from plain brass.

If you are shooting military surplus made outside the U.S. beware of Berdan primed cases as well as steel cases. Steel case ammunition remains very common in the former Soviet Union. The pre-Soviet Russians managed to perfect their process for making steel cartridge cases. That and the cost efficiency has kept the Berdan primed steel cartridge case alive and well. Berdan primed cases can be reloaded, but it requires equipment not commonly found in the U.S. or Canada. Trying to load a Berdan primed case with normal reloading equipment can cause serious damage to your dies and press.

Cartridge brass starts its life as a slug of brass in the shape of a cup. It is then extruded in sizing presses until it gets to its sort-of-general size and shape. The case head is shaped and stamped with the manufacturer’s name and caliber of the cartridge. Military cases have a totally different headstamp protocol. Military cases are usually identified by the manufacturer’s initial, usually two or three letters, and the year of production. Once the case is finished into its desired configuration, it goes for a form of heat treating. Brass must be tempered to be elastic enough to be able to expand in the firing chamber, contract sufficiently to facilitate extraction and ejection, and strong enough to survive the loading, firing and extraction process. It is a lot to ask of this metal, and preparing it properly will only extend its service life. Once you have all your cases collected, it’s time to clean them.

Cleaning the brass is essential for a number of reasons. One is to clean out any loose residue that might be inside the case, and secondly, it is to clean the exterior of the case. This is not for cosmetic purposes. It is being kind to your rather expensive reloading dies. Dies are not cheap, and care will guarantee long life. Dirt is very abrasive and will very quickly score the sizing die’s compression ring and leave scarring on every case you reload from then on.

Cleaning the brass involves the use of a vibratory case tumbler, such as available from sources like Dillon Precision, Midway USA, and Frankford Arsenal, just to name a few. You will need at least one type of tumbling media that is available in bulk online. For really dirty brass, ground walnut shell media is the abrasive that is needed to scrub the dirt and tarnish off. After tumbling in walnut shell media, tumbling your brass in ground corn cob media will give it a lustrous shine. If your brass is relatively clean to begin with, the ground corn cob media brings a shine to brass rivaled only with commercial brass cleaners. Polish solution should be added to the media. Probably the best liquid case cleaning polish on the market for reloaders is available from Dillon Precision, and can be ordered online. Used sparingly, you will get surprising results.

After the brass is tumble cleaned, it needs to be separated from the media, and once again, there are several sources for a separation strainer and media capture. The recovered tumbling media can be reused many more times than one might think.

PRIMERS

This tiny little device is the ignition source that makes your ammo go ‘bang’. It is to firearms what the spark plug is for a gasoline engine. To fully appreciate the very important role this tiny part plays in making small arms ammunition work, it helps to understand how we got to the primers of today.

Early percussion caps were developed in the early 1820s. Initially they were used on converted flintlock rifles by hunters that wanted instant ignition that would not spook game animals the way the traditional flintlock did. No longer did one have to put loose gunpowder in an open pan and hope that striking a flint against the frizzen (what at that time was called the hammer) would ignite the powder in the pan, and in turn ignite the powder charge in the barrel. Moreover, the percussion caps could be carried in a pouch to keep them dry. The concept spread faster than bad office rumors of the boss and under-age sheep. It was not long before the percussion cap was used in nearly every black-powder-era firearm around: By the 1850s, flintlocks were relegated to hanging over the fireplace as relics of a time gone by. Revolvers, pistols, rifles, and shotguns all now used the percussion cap to ignite the black powder charge in the muzzle loading weapons of the era. The percussion cap enabled Samuel Colt to come up with his design of the revolver. No sooner had the percussion cap become the standard than work was already being done to move the primer from the gun itself to the cartridge.

Two inventors came on the scene who changed the game. Col. Hiram Berdan was an American who devised a small brass cup filled with priming compound that would fit into a pocket in the head of a cartridge. Inside Berdan primed cases, there was an anvil made into the case itself to support the priming compound. Berdan received a patent for his primer in 1866. Meanwhile, in England, Col. Edward M. Boxer was an inventor with the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich, England, and his version was similar to Hiram Berdan except for one aspect which would be significant. The Boxer designed primer had a support anvil inside the cup itself. This self-contained anvil held the priming compound in place and facilitated even ignition. The irony is that the Berdan primer, invented by an American, became the standard in Europe, Asia, the UK, while the Boxer primer became the standard in the United States and Canada. The Boxer primer was patented in England in 1866, and in the United States in 1869. We should be thankful that the Boxer primer is our standard as it makes reloading so much easier.

With these two primer types more or less perfected, work commenced almost immediately on the self-contained cartridge and moving the percussion cap from a nipple on the cylinder or receiver to the cartridge itself. Much of this was spearheaded in the United States by Smith & Wesson. By the late 1860s, the centerfire cartridge had come into being, again from Smith & Wesson. The roadblock to how we know the revolver today came from S&W. They held the Rollin White patent on the bored-through cylinder, and it was not until 1872 that the patent expired and all revolver technology broke loose. The Colt Single Action Army and the S&W Model #1 top break became the revolvers of both the U.S. Army as well as the rest of Americana with both using self-contained cartridges. For us revolver guys, the rest as they say is history.

As wonderful as these new self-contained primers were, they had a serious drawback. They used fulminate of mercury, potassium chlorate, sulfur and charcoal. While far more reliable than the flintlock and percussion lock, they were still somewhat unstable, and highly corrosive on gun steel. Cartridge brass was not viably reloadable since the mercury in the primers made the cartridge case brass brittle. Every time you shot your firearm, you had to clean it if you did not want to find it pitted beyond use. Despite formulation changes, the fundamental problems with chlorate primers would not change until the German company RWS substituted the potassium chlorate with barium nitrate. Lead styphnate was now used instead of fulminate of mercuric as the main explosive component giving the first ‘rust free’ primer. This was patented in 1928 under the name Sinoxid. Thus, the non-corrosive primer was born.

There were still teething pains with this new compound, and the U.S. military continued the use of corrosive primers until 1945. The exception being ammunition for the .30 M1 Carbine, which was always loaded with non-corrosive primers. The British did not discontinue corrosive primers in military ammunition until the 1960s. The Soviet Union discontinued corrosive primers when they disintegrated in 1991.

Needless to say that World War II caused a pause in non-corrosive primer development. It was found that by adding an itsy-bitsy small amount of ground glass to the priming mixture, it gave it the necessary abrasiveness to now make it totally reliable. A note of caution: surplus ammunition from the former Soviet Union and other Communist countries is highly corrosive and your firearm should be cleaned accordingly. Modern commercial ammunition from Russia uses non-corrosive Berdan primers with steel cases making economical ammo available. Today we enjoy the most reliable and cleanest primers to be found anywhere. Sources such as Federal, Winchester, Remington, and CCI all produce state-of-the-art primers.

Boxer Primers come in many sizes and power ratings. You will find the following common sizes: Small Pistol, Small Pistol Magnum, Large Pistol, Large Pistol Magnum, Small Rifle, Small Rifle Magnum, Large Rifle, Large Rifle Magnum, and those designed for Shotgun shells. Using a magnum primer versus the standard primer will invariably affect ignition temperature and chamber pressures, so you need to follow the reloading guide. Twenty years ago, primers were a penny a piece. Going prices at this writing is about 4 cents a piece in bulk.

GUN POWDER

This choice is based on what cartridge you intend to load and what weight bullet you intend to use. As a rule, faster burning powders are ideal for light target loads, while slower burning powders are better suited for heavier bullets and more powerful loads. The first item you will need to procure is a powder scale. Balance Beam scales are available online from Brownells, Midway, Dillon and others. I’ve used this type of scale for over 40 years and find that it remains absolutely reliable. Simple is sometimes best.

Reference was made in the beginning to loading manuals. Study what type of load you intend on producing and pick your powder of choice. Also choose an alternate in case inventory issues arise. Hodgdon manufactures most of the better-known names in commercially-available powders for reloaders such as all of the Winchester Ball powders, Accurate Arms, and IMR/SR (Improved Military Rifle / Sporting Rifle) powders. Again, Hodgdon also provides loading data for anything their powders are suitable for.

Alliant, formerly known as Hercules, is another excellent manufacturer of powders that fills in some gaps that might exist in other brands. Their line includes long-used names like Unique and Bullseye.

VihtaVouri is based in Finland and makes a variety of powders for handgun, rifle, and military use. Their powders are blended for maximum performance at reasonable chamber pressures. As an example, VV has an excellent powder, 3N37, that was designed specifically for 9mm NATO to give +P+ performance at +P pressures.

Most reloading manuals include handgun data using shotgun powders. This is not a mistype, as several shotgun powders are easily adaptable to higher-power handgun loads. As you go along in reloading, you’ll find you have several different powders you use for various bullets. Don’t worry, it is perfectly normal.

CHOICE OF CARTRIDGE

Since this is addressed to RevolverGuys, I’ll focus on a cartridge that I have been loading since shortly after the Earth cooled: The .38 Smith & Wesson Special.

Much has been written on the history and development of this fabulous cartridge, so I won’t repeat the volumes already written in the public domain. Suffice it to say that the .38 Special is one of the easiest, and perhaps THE most forgiving cartridge for reloaders in existence. It can handle bullets ranging from 90 grains to 180 grains, all with loads ranging from heavy bowling pin busters to featherweight target loads. Much the same can be done for other revolver cartridges such as the .44 S&W Special and the .45 Colt.

The .38 Special is a superb target round. Reloading offers the opportunity to create some excellent training rounds for those that are new to handgun shooting. Loaded with 148 grain wadcutters over 2.5 grains of Winchester W231, it is almost monotonously gentle to shoot. With a different powder charge, or different powder, under a traditional cast or jacketed bullet, you can duplicate factory-loaded ammunition to train with what you would carry on the street. In my earlier years on the job, we were issued S&W .357 Magnum revolvers and used .357 ammunition. I would reload practice magnum rounds that would duplicate the recoil, and point of impact of our issued ammunition. Qualification time was not all that dramatic with that practice method. The combinations of powder charges and bullet design and weights are far too extensive to list here – that’s what your powder and bullet manufacturers’ load data is for. These manuals are not published whimsically. Remember, half the fun of reloading any cartridge is the ability to customize your favorite load. It’s all about creativity.

THE BULLET

This one component has so many variations that it is either a reloader’s dream or nightmare. To someone new to reloading, the vast number of different bullets available in most any caliber can be mind-boggling. Do you want light weight and high velocity, heavy weight with lower velocity, or something to approximate factory loads.

The .38 Special has seemingly endless choices from bullet manufacturers such as Speer, Hornady, Nosler, Remington, Winchester, just to name a few. Factory bullets offer a few advantages, mainly weight and size consistency. All of these manufacturers offer jacketed bullets. The jacketed bullet usually has a lead core with a thin layer of copper plate that forms a cup in which the lead is injected. The advantage of copper jacketed bullets is their ability to be driven at much higher velocities than plain lead. They leave zero lead residue in the cylinder and barrel that makes cleaning much easier. Their downside is cost. You will pay for that cleaner shooting to the tune of an average fifteen to twenty cents per bullet alone. That does not sound like a lot until you add up an afternoon of shooting that tallies 50, 100, or 150 rounds.

Bullets On The Cheaper: There are many companies you can find on line that have commercial bullet casting operations. You can buy these cast and sized bullets in bulk of usually 1000 at a time. They are usually 2/3 to 1/2 of the cost of jacketed bullets. Berry Bullets are renown for offering copper plated cast bullets. These are not copper jacketed like mentioned earlier. These have a very thin copper plating to reduce lead contamination. They are a very cost efficient alternative to conventional jacketed bullets. Another more recent technology pioneered by Federal and their line of Syntech handgun ammunition. The bullet has a synthetic polymer coating that prevents any metal to bore contact. Think of it as polymer powder coating. This technology is used by other bullet manufacturers such as Eggleston Bullets. The coating is available in a host of colors to brighten up your ammunition, or even color code it. I have been loading Eggleston 158 grain lead semi wadcutter polymer bullets in .38 Special with rather good results.

Bullets On The Cheapest: When I started reloading I discovered casting my own bullets. At the time my process was primitive. Along my work route, I arranged for several tire places like Firestone, Goodyear and others, to toss their old wheel weights in a bucket. Wheel weights are already alloyed with enough tin to make them hard enough to withstand their life on vehicle wheels. I would bring them home, wash them all down to get the road dirt and oil off of them, and then melt them into ingots in my Lyman lead furnace to use later. Lyman is an excellent source for equipment and supplies for the bullet caster. You can get nearly any weight and configuration imaginable. With a mold that would create four bullets at a time, a 5 gallon bucket of cold water and a ladle, it was easy to have upwards of 500 or more bullets cast in a lazy afternoon.

Working with lead can be toxic. Lead can be easily absorbed through the skin and respiration, and the end result can be deadly over time. Lead does not naturally purge from your system, and has to be chemically treated in a process called chelation. This process must be done under medical supervision. Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) are the two primary FDA approved compounds used to remove heavy metals from the body. The side effects of chelation therapy include dehydration, low blood calcium, harm to kidneys, increased enzymes as would be detected in liver function tests, allergic reactions, and lowered levels of dietary elements . It is a very long and unpleasant process – ask me how I know! Wear gloves and respirator while casting or working with molten lead, bare lead bullets and tumbling media. Wash yourself (and your clothes) thoroughly after any casting session, any reloading session, and after any range session involving bare bullets – especially if you are frequenting an indoor range. Do NOT ever trust the ventilation at public indoor ranges. The air quality ranges from so-so to totally hazmat conditions.

After casting comes final sizing and lubrication. Lyman equipment makes this rather easy to size your .38 Special bullets to their ideal size – .358 inch diameter. The total cost was not measured in the lead – that was free scrap. The cost is measured in time, and cost of bullet lubricant – figure half a penny per bullet.

THE RELOADING PRESS

There are many makes and models of reloading presses available to the consumer, ranging from a simple RCBS or Lee single stage press to Dillon’s advanced progressive loaders. Since my discovery in the early 1990s of Dillon Precision products, I have become a devotee of their progressive presses. I urge you to check them out online. They have everything from basic manual operations to some very sophisticated semi-automatic functioning machines.

My first reloading device was an RCBS single stage press that I still have. The first cartridges I loaded were for a surplus German Mauser Kar98k that my grandfather had given me. It was in the venerable 7.9x57m/m Mauser It was slow going: size all the cases first, the prime them, then add the powder charge, then sit the bullet atop the case mouth, and the seating and crimp die finishes the job. I got to where I could reload all my 40 rounds of brass in about two hours. I still have the very first round for that Mauser that I ever loaded. I used the same press to start loading .38 Specials, and things took off from there.

The Lee 1000 semi-progressive was my next experience with faster reloading of handgun rounds, and while it was a step up from a single stage press, it had more issues than a Russian ZIL on a tow truck. That Lee lasted about a year until I was introduced to Dillon Precision. In 1994, I took the dive and obtained a Dillon XL650 with complete conversion kits, tool heads, and dies for the five cartridges that I reload. I also got the auto case feeder, and spent about half again more than I had planned. I wondered whether it was worth it. It was more than worth it as it paid for itself in a little over a year. I never looked back from that point. My advice is that if you are serious about reloading, get the best unit you can afford, and then go a bit higher. If you plan on doing a lot of reloading, they are well worth the money for the time you will save. Think of it as spending a dollar once instead of a quarter seven times.

The new Dillon XL750 is perhaps the most practical progressive loader on the market. As for the old RCBS single stage press, I still use it for load development when I only need 10-15 rounds of a given powder/bullet combination to test out.

THE PROCESS

Have all the components you will need assembled. Primer supply is staged and ready. Powder measure is calibrated for the load you have chosen, and a tray of bullets is within easy reach. You have calibrated your loading dies, and you are essentially ready to go.

If you are using a progressive loader, when you operate the handle, the rotating case plate is lifted up against the dies in the tool-head, and then on the down-stroke, the case plate is advanced through each stage of the loading process.

First step is putting an empty case into the case plate on stage one. On manually-operated progressives like the Dillon XL550, this is done manually. On those with automatic case feeders, it is done for you – more or less.

The first down-stroke of the operating handle and the cartridge case is lifted and squeezed into the sizing die. The carbide sizing ring does a slight shrink job on the brass to bring the case back to its original size and pops out the spent primer. On the Dillon 550, the case indexing is done manually; on other Dillon machines, it is automatic.

The next stage is to insert a new primer into the case. The priming is done when the case is lowered against the primer ram and you gradually nudge to seat the primer. In nearly all loading machines, there is going to be a learning curve of feeling the right amount of pressure and knowing when the primer has been seated. It is like driving a stick shift vehicle – every clutch feels slightly different.

After priming the cartridge, next is the powder charge. The charge station dispenses a pre-measured amount of power. At the same time, it slightly flares the case mouth to facilitate seating the bullet.

Seating the bullet starts with setting the new bullet atop the case, and carefully guiding it into the seating die. After the bullet is seated, the final stage crimps the case to secure the bullet into place.

You now have your reloaded .38 Special cartridge. Repeat this a couple of hundred times, go wash up, pack your range bag and your favorite .38/.357 revolver and go enjoy the fruits of your labor.

Good article. Reloading is both fun and gives the satisfaction of making your own good quality ammo. Plus you also can play with some odd loads like round ball loads.

Stuart,

Excellent article and advice for anyone considering getting into reloading! I wish I would have read something similar 35 years ago when I was bitten by the reloading bug it would have saved me some headaches. The 7.92×57 was the second cartridge I loaded for. I aquired a surplus Mauser from a friend. Good memories! Hope to see more from you in the future!

Best regards,

Morgan

It’s nice to see a post on reloading here- thank you for the excellent article, Mr. Bond! Loading your own certainly gives some added security in times like these when there’s no ammo to be bought. It’s also a therapeutic pursuit when you’re stuck at home because of this plague and its sanctions. The same can be said about casting bullets. Like Mr. Bond points out, the .38 Special is a natural for homebrewing and it excels with cast bullets. You can get a lot more out of most revolver cartridges by reloading, and custom build ammo to do exactly what you need. Good stuff!

The first thing to do if you are interested in reloading is buy a manual and read it. Ignore the data and read the front of the manual. Read the theory and understand it. Yah I know, I didn’t do this when I started either. I probably reloaded for 10 years before I actually read the front of the book. These manuals are written by very experienced folks who have forgotten more than most folks know. If you do as I suggest you will understand the variables and how to deal with them from the start and you will be much safer.

Excellent advice, Brett. Thanks.

I also liked Stuart’s advice to get SEVERAL good manuals, because it’s useful to compare the loads against each other in different sources.

Very true, Brett. Different manuals approach the same subject matter from slightly different angles. There’s no such thing as too much information when it comes to reloading your own.

I want to take my first dip into the reloading pool but I’d sure be more confident if I had a veteran reloader show me the ropes. Hands on training. A dear friend of mine was that guy but went to be with The Lord recently.

Henry, it’s been my experience that reloaders love to share their hobby. There’s probably a few guys at the range who would love to give you a tour of their setup and coach you along. The hard thing right now is to find primers during this crisis.

I have always wanted to get into reloading. But it has always been an issue of space and time for me. Eventually I will do it. I like the idea of starting with the simple single stage to make small batches for testing and then using the progressivist for mass production. As an on again, off again local competitive shooter I see a lot of bad ammo that was reloaded. Many of them loaded hundreds of rounds before actually shooting them to see how well they worked. Expensive lessons in time and money.

Keith, using a single stage press for experimental loads is just where I started my load workups. Loading 12-18 rounds for the wheel gun and a brief run to the range will tell you very quickly whether you have a good load or a not so good one. If you’re blessed with a chronograph, well, even better.

You have to get on the merry-go-round at some point. : )

Here in Brazil, ammunition is VERY expensive. Training with factory ammo is finnancially impossible.

Centerfire ammunition is sold in Brazil in 10-round blisters, that cost the same that a 50-round box in the USA. Even cracked .38 Special cases are often shortened and transformed in .380 Auto for maximum economy…

Another problem was the recently revoked caliber restrictions. Some Brazilian shooters made abusive reloads to obtain .357 Magnum pressures on .38 Special ammo, with disastrous results. But it’s past now.

Reloading for revolvers is especially rewarding with how much flexibility and options you can choose from. For example, .357 cartridges can have the bullet deep seated to .38 special overall length and use .38 special powder charges to avoid carbon rings in .357 chambers. Rounds can be loaded light for new shooters and for economical range sessions. Rounds can also be loaded much heavier-some Rugers can utilize “Ruger only” loads with heavy bullets for big game hunting applications. Casting your own bullets can allow you to size them perfectly to your individual barrel. You can also build a bullet trap and recast your lead indefinitely. Lots of benefits to revolver owners who reload (and you don’t have to pick up used brass off the ground]!

Thanks Joshua! Those are some excellent points. Glad to have you aboard.