There was a revolution in police handguns happening in the 1980s, as American police officers increasingly said goodbye to their double action revolvers and replaced them with semiautomatic pistols.

The semiautomatic certainly wasn’t new to policing. A number of agencies had issued or approved them for duty use prior to this time, but it was in the 1980s that the slow trickle of police autopistols became an unstoppable torrent, and changed the face of American policing.1

TWIN TRAGEDIES

At the time, there was a growing contention in police circles that officers were being “outgunned” by domestic terror groups, drug traffickers, and hardened criminals armed with superior weapons. The concerns alone were enough to prompt some police administrators and civic leaders to support a rearmament program, but in other locales, it took actual line-of-duty deaths (LODDs) to generate the necessary inertia for change.

Two such influential losses were the murders of New Jersey State Trooper Philip Lamonaco, and New York City Police Officer Scott Gadell. The deaths of these men promoted change within their respective organizations, and are worthy of our attention, not only to understand the history behind the revolver-to-auto transition, but for the officer safety lessons they provided.

GROUND RULES

We’ll focus on the Lamonaco shootout in this installment, and will look at the Gadell shootout in the next.

However, before we begin, it’s important to note that while the analyses of these gunfights may be critical of the officers’ actions at times, and highlight errors in tactics and decision making, my sole intent is to be constructive. Nothing I say should be construed as a personal attack on the involved officers or their legacies. I have the greatest respect for these men, their families, and their fellow officers, and aim to educate with these observations, not insult.

In my experience and opinion, the greatest insult to these officers would be to ignore the lessons that their sacrifices highlighted. If we fail to learn from them, then we have failed them. As such, I’ll “call ‘em as I see ‘em,” and will rely on you to receive and use the information in the spirit that’s intended.

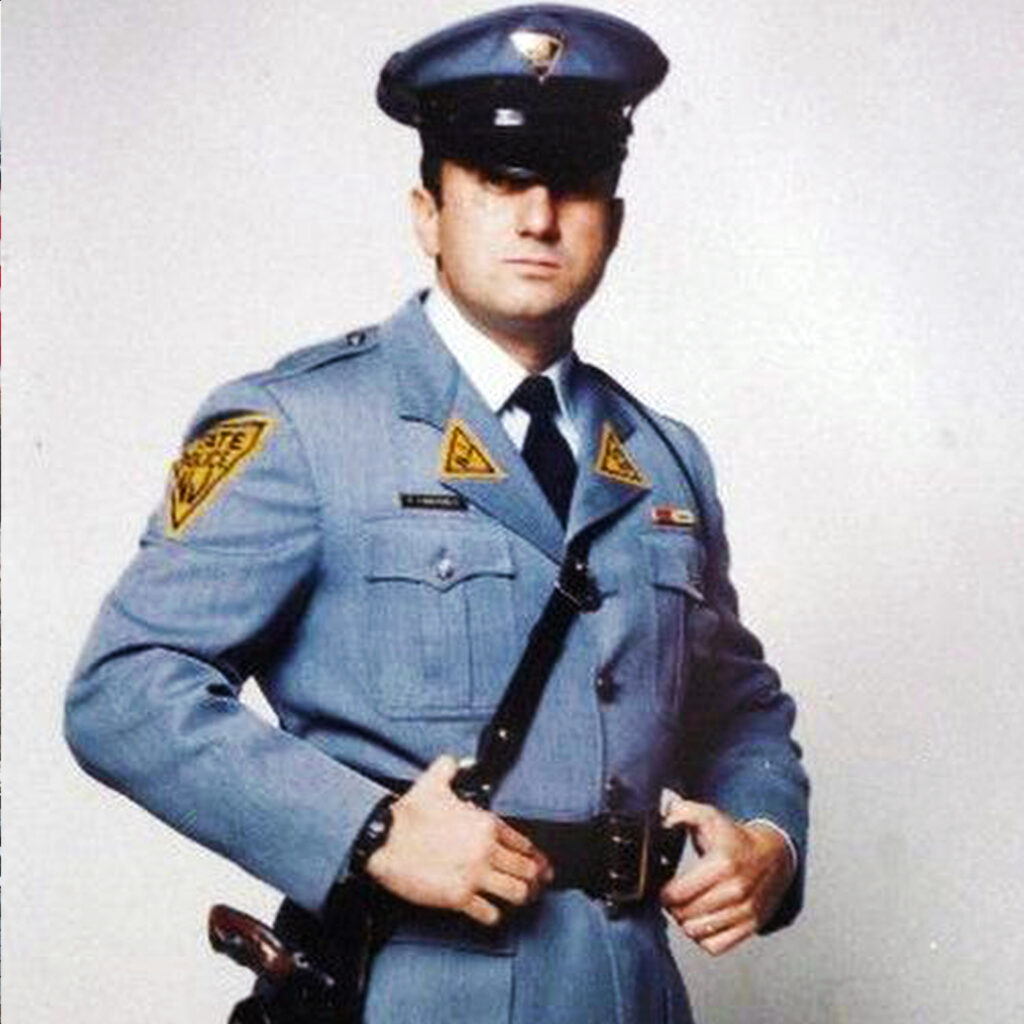

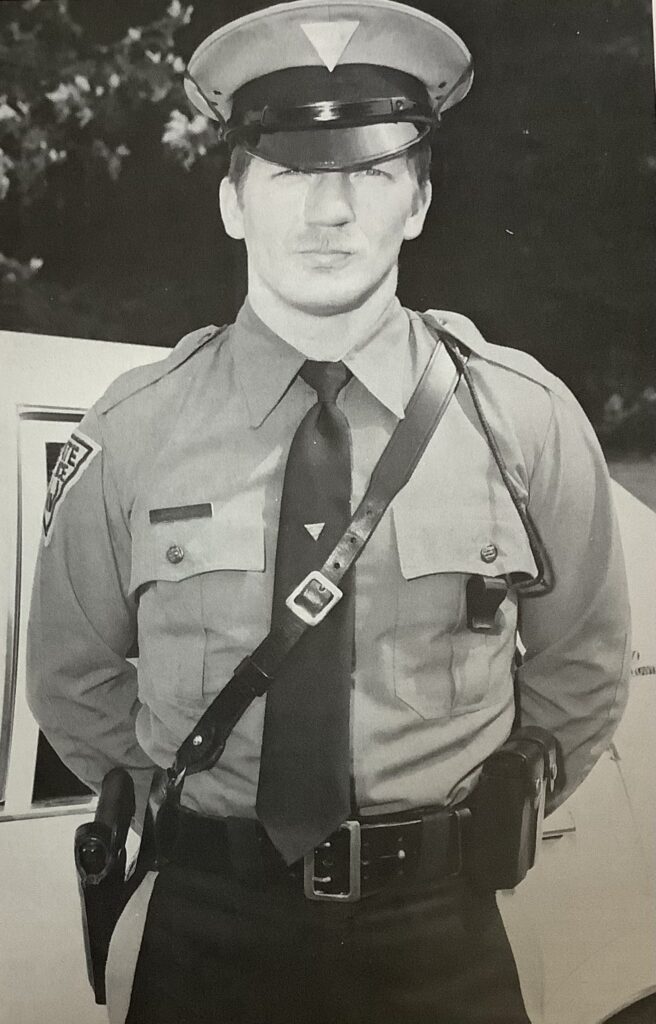

A TROOPER’S TROOPER

Trooper Philip Lamonaco was an eleven-year veteran of the New Jersey State Police, assigned to the barracks in Blairstown Township (since relocated to Hope Township). He was greatly respected by his peers and supervisors as an aggressive, hardworking Trooper with a knack for picking bad guys out of the traffic flow. 2

In 1979, he’d been honored by the state as the “Trooper of the Year,” with his citation proclaiming that Trooper Lamonaco was, “responsible for initiating 44 separate patrol related investigations, resulting in the arrests of 66 persons, and the seizure of illicit contraband valued in excess of $500,000.” The awards board noted his courage, as part of the award. 3

Trooper Lamonaco was also singled out as “one of 82 state residents who bear watching in 1982” by the New Jersey Monthly magazine, who called him a “Super Trooper” in their coverage. The magazine credited Lamonaco with making more than 200 arrests in the last three years, and participating in two major roundups of drug suspects in Warren County. He was also credited with assisting in the recovery of $2.5 million in stolen property. 4

Lamonaco was one of the most-decorated troopers in the state, so when he made a plea to union leadership in late 1981 to fight for increased manning–“Mr. President, we need more manpower out there, we need more backups, because someone is going to get shot and killed”—he had everyone’s attention.5

Ironically, he would be murdered on duty a month later, just four days before Christmas—the first trooper shot in the line of duty since 1973.6

A FATAL STOP

Trooper Lamonaco was an expert at intercepting suspicious vehicles along New Jersey’s Interstate 80 corridor, frequently discovering stolen vehicles, drug runners, and a variety of mobile criminals, so it was probably no accident that he pulled over the blue, 1977 Chevrolet Nova with Connecticut license plates, around 1615 on 21 December 1981.

Inside the car were two members of the Sam Melville-Jonathan Jackson Unit (SMJJU), a radical, domestic terror group whose members committed approximately 19 terror bombings and 10 bank robberies between 1975 and 1984.7 The driver, Thomas Manning, was a violent ex-con and one of the founders of the group, while the passenger, an ex-con named Richard Williams, was a relatively new recruit to the SMJJU.8

The stop occurred on Interstate 80 in Warren County, about four miles east of the Delaware Water Gap, at the foot of an exit ramp from the westbound lanes.9 It’s not clear why Trooper Lamonaco made the stop—perhaps it was for speeding, or some other “routine” reason, or perhaps his finely-tuned senses “hit” on the car full of armed terrorists. Either way, he didn’t call in the stop to dispatch.

At Lamonaco’s request, Manning produced a (false identity) driver’s license, which would later be recovered from the top of the vehicle’s dashboard. As Lamonaco interviewed Manning on the shoulder of the interstate, he noticed the butt of a 9mm pistol in his waistband. Lamonaco reportedly removed Manning from the vehicle, disarmed him, and tucked the pistol behind his Sam Browne belt, to secure it.10

As Trooper Lamonaco continued his search of Manning, Williams leapt from the passenger side of the car with his own 9mm pistol and fired at the trooper. Lamonaco fell to the ground, probably after being pushed by Manning, then got to his feet, and moved from the driver’s side door around the front of the Nova, to get a better angle on Williams at the right front passenger door.11

Lamonaco fired all six rounds from his 4” Ruger Security Six revolver at Williams, as he moved around the front of the vehicle. Several of the Winchester-Western, 110 grain, .38 Special +P JHP rounds impacted the hood of the car–perhaps early shots, as Lamonaco tracked his weapon upwards from the holster, towards Williams. The windshield was struck at the bottom, center edge, possibly by a ricochet from one of the rounds that struck the hood, as the hole it left behind in the glass was enlarged and oblong.

Additionally, the windshield was struck several more times–perhaps as many as three–in a tight cluster, near the upper corner on the passenger side. The passenger side door window was also shot out by Lamonaco’s gunfire, and the car’s rear window was shattered, perhaps by one of the rounds that penetrated the windshield, passed through the passenger compartment, and punched through the window from the inside, out.12

Although Williams was wounded by Lamonaco’s return gunfire, he still managed to fire an estimated eight to twelve rounds of 9mm at the ambushed trooper.13 Three of those rounds struck Lamonaco in the chest, but they were stopped by his early-design, Point Blank body armor.14 When the trooper fell to the ground, Williams fired an additional two rounds which struck Lamonaco in areas unprotected by the vest, including a fatal round that entered his chest through the left armpit.15

As Lamonaco lay dying on the side of the road, Manning retrieved his pistol from the downed trooper, then drove away from the scene with Williams. They abandoned the car about six miles from the shooting scene, after it got stuck in a snowbank on rural, Station Road in Knowlton Township, and fled on foot.16

A passing motorist stopped to check on the apparently abandoned State Police car, and found Trooper Lamonaco face down in the snow. He used the car’s radio to summon help for the badly injured trooper, and troopers from the barracks and surrounding patrol areas rushed to the scene, where they found Lamonaco and his empty revolver. Trooper Lamonaco was transported to the Pocono Medical Center, where he later died.17

Roadblocks were established and the surrounding areas were canvassed to identify and catch the suspects. A motorist gave the police information about seeing a blue Chevy Nova drive away from the scene, providing the first useful lead. The car was located several hours later, with bullet holes in the hood and glass, bloodstains on the inside of the passenger side door, the passenger side armrest, and the passenger side headrest, and an empty holster inside. Police also found the fake driver’s license on the dash, which eventually helped them to identify Manning.18

Manning and Williams were eventually caught and tried for Trooper Lamonaco’s murder. Manning was sentenced to life in prison for the murder (and 53 years for domestic terrorism), and died there in 2019. Williams was acquitted for the murder, but imprisoned for committing domestic terror acts, and died in prison in 2005.19

CATALYST FOR CHANGE

The Lamonaco shooting prompted an outcry from the members of the New Jersey State Police, who had previously suffered the death of one trooper at the hands of domestic terrorists armed with semiautomatic pistols (Trooper Werner Foerster, in 1973—See Endnote #6), and now had lost a second, under the same circumstances.

The murder of Trooper Lamonaco was especially chilling, given his sterling reputation. Thomas Iskrzycki, the president of the New Jersey State Police Fraternal Association, recounted later that, “there was a terror that went through every man and woman in this organization. We said . . . when one of the best guys we have gets shot, that means any one of us can be taken down.”20

Despite their shock and grief, Iskrzycki and his troopers knew they had an opportunity that had to be seized. “We more or less capitalized on it as a psychological advantage,” said Iskrzycki, who noted that, “within two months we got everything we were asking for.” 21

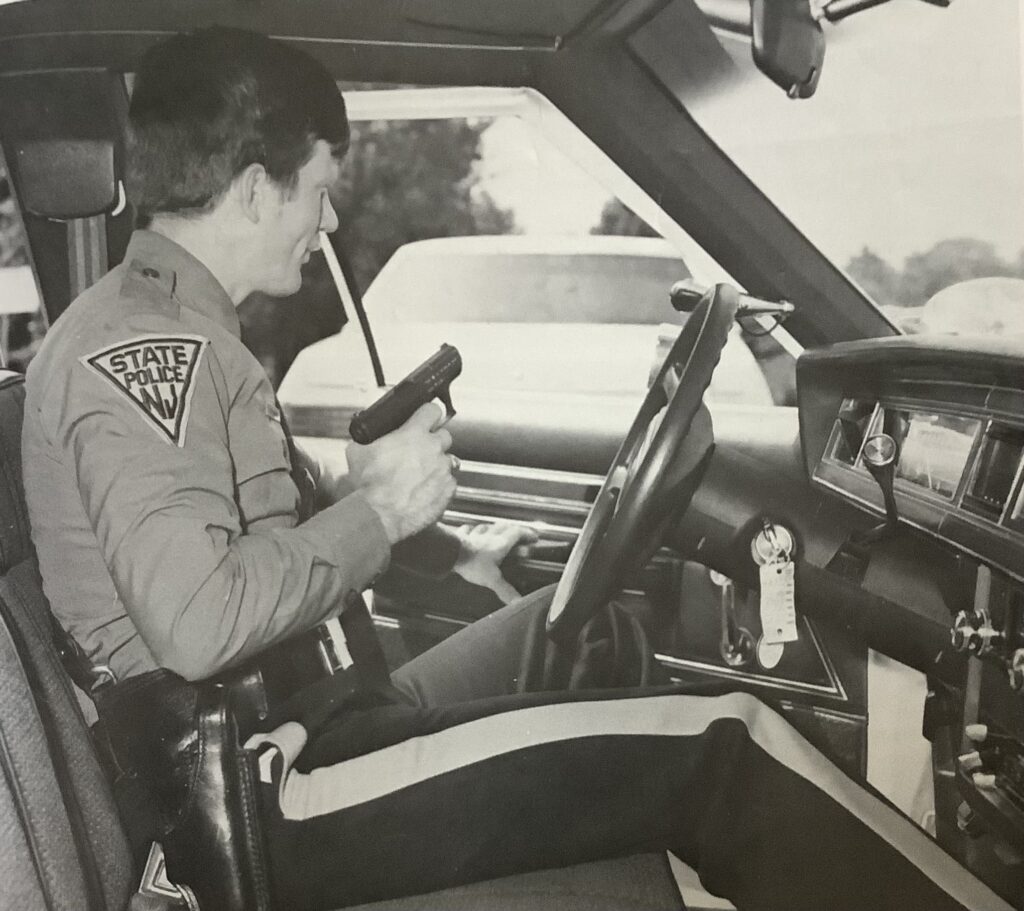

The troopers and their union found a sympathetic audience in New Jersey State Police Superintendent Clinton Pagano, who reportedly took Lamonaco’s murder personally. Colonel Pagano ordered a test and evaluation program almost immediately after Trooper Lamonaco’s death, and by early 1982, the NJSP had selected the 9mm Heckler & Koch P7M8 to replace their Ruger Security Six (GA-34) revolvers. Troopers would carry the new, 9-round pistol (8+1) with four additional 8-round magazines, for a total of 41 rounds on tap, in their duty configuration. Previously, the troopers had carried 30 rounds of spare ammunition for their revolvers, in a pair of cartridge loops mounted above the duty holster. 22

A PAUSE, FOR CRITICAL ANALYSIS

We certainly don’t begrudge the troops in New Jersey from using the Lamonaco shooting as ammunition for desired equipment changes, because the exercise seems to be an inescapable part of the dynamic of military and law enforcement professions.23

We also won’t argue against the sentiment that the time had come for the greater American law enforcement community to embrace the autopistol. The revolver served generations of American lawmen well, but times had changed, and the case for the auto as a general issue service weapon was strong, and getting stronger.24

However, in the interest of accuracy and officer safety, it would not be fair to lay the blame for Trooper Lamonaco’s death solely at the feet of his issued equipment. It would be intellectually lazy to blame his death chiefly on the limited capacity of his revolver, as the law enforcement community chose to do. Additionally, it would be a waste of Trooper Lamonaco’s sacrifice to ignore the other important officer safety lessons from his deadly encounter with Manning and Williams.

LESSONS

There are numerous officer safety lessons we can learn from Trooper Lamonaco’s example that don’t have anything to deal with ammunition capacity. Some of these include:

-

- Communication. Trooper Lamonaco did not report the vehicle stop to Dispatch, which potentially robbed him of assistance. We’re not sure why Lamonaco chose to stop the vehicle—was it for a “routine” matter, like speeding, or did he detect something more serious? Had he reported the stop to Dispatch as a high-risk stop, it likely would have generated backup for him. Even if he only reported a low-risk, “routine” stop, other unoccupied troopers may have done a drive-by, just to check on him—a common occurrence, then and now.

Reporting the stop may also have triggered Dispatch to send an officer to check on him, when he didn’t return on the air in a reasonable amount of time. It was wonderful that a concerned citizen eventually came to his aid, but an earlier discovery of the wounded trooper may have improved his chances of survival.

Lastly, reporting the stop might have allowed Lamonaco’s fellow troopers to more quickly locate the suspects, after they fled. It took a while for the troopers to get a lead on the type of vehicle they were looking for, but if they had started with that information, it’s possible they could have caught Manning and Williams quickly, before they escaped, and recovered evidence that would have made it easy to convict both of them for Lamonaco’s murder.

It’s important to note that Trooper Lamonaco’s only radio was in the car. In just a few years, portable radios would become common in law enforcement, but once Trooper Lamonaco moved forward to the suspects’ vehicle, he had no ability to radio for assistance —a factor which made his decision not to report the stop even more critical. In these circumstances, good risk management would suggest making an early advisory call to Dispatch.25

There’s no way to know if anyone would have arrived in time to help Lamonaco during the gunfight, if he had called for help, but by failing to call in the stop, Lamonaco guaranteed he’d fight it solo;

-

- Tombstone Courage. One of the founding fathers of the “Officer Survival” movement in the 1970s was LAPD Homicide Detective Pierce R. Brooks, who wrote his seminal work, Officer Down, Code Three, in 1975. In Officer Down, Brooks identified his list of “deadly errors” committed by policemen, one of which was “tombstone courage,” which he defined as, “the unnecessary risks and acts often committed by police officers in the line of duty.”

It would be easy to write this off as a simple function of hubris or ego, but that’s not necessarily the case. The odds are excellent that Lamonaco had a number of “close calls” in his eleven years as a trooper, where he made mistakes or was overwhelmed by conditions while working alone, but managed to retain or regain control, and escape serious harm, by a combination of wit, skill, and luck. Perhaps Lamonaco’s successes, and the experience he gained from them, eventually made him feel comfortable with assuming too much risk, because he’d always managed to pull it off, before.

Trooper Lamonaco had a demonstrated history of aggressive policing, which produced excellent results. He was widely admired for his confidence, courage, tenacity, and self-sufficiency—qualities that made him an excellent and successful trooper, and brought him a fair degree of recognition.

Yet, those same qualities may have led him to assume more risk than he should have in the stop of Manning and Williams. Once again, we don’t know why Lamonaco made the stop, but it’s not unlikely that his finely-tuned cop senses told him something was “off” with this pair of terrorists masquerading as motorists—maybe not early in the stop, but certainly as it developed. Did he hear a voice warning him that these guys were up to no good, and did he dismiss it because he felt like he could handle it by himself? Did he feel like it would have been cowardly for a “Super Trooper” like himself to ask for additional help on a suspicious stop that could turn out to be nothing?

We’ll never know for sure, and it would be just be speculation to guess, but it would have been consistent with his history of service to tackle difficult jobs by himself, and it wouldn’t have been the first time that an officer put himself at undue risk in a display of tombstone courage. It’s certainly a consideration for other officers to think about;

-

- Agency Culture. It’s also worth pondering if the culture of the NJSP encouraged Trooper Lamonaco to handle the stop by himself, without reporting it on the radio.

It’s common for troopers, highway patrolmen, game wardens, and rural deputies to operate in areas where there is often no immediate backup available, and these lawmen are frequently expected to handle their duties without assistance. In circumstances like these, it can become part of the ethos or culture of an organization, and part of an officer’s expectations of himself, to tackle calls alone, even when backup is available and/or advised.

We know from his testimony at the union meeting that Trooper Lamonaco was concerned about the NJSP’s manning, and we also know he had a long history of handling calls alone, as troopers of the era were expected to do. Perhaps this conditioning primed him to handle the traffic stop alone, without calling it in, because he figured backup would be unavailable anyhow, and it was “just part of the job.”

Based on Trooper Lamonaco’s example, today’s officers would be well-advised to consider how the culture they work in may encourage bad tactics, decisions, and outcomes, and be prepared to combat it;

-

- Tactical Withdrawal. Whatever the reason for the stop, it should have been immediately clear to Trooper Lamonaco that things were starting to deteriorate, when he saw the gun on Manning. If the investigators were correct in their belief that Lamonaco spied the gun in Manning’s waistband as he sat in the car, then removed Manning from the car to disarm him, we have to consider how things may have gone if Lamonaco had chosen not to press the contact at that time and place.

If Trooper Lamonaco had coolly returned the driver’s license, and sent the pair on their way with a verbal warning to “watch their speed,” he could have followed them at a safe distance and enlisted help to stop the pair again at a time and place downstream that was more advantageous to the troopers. Alternatively, if he had left the men seated in the car, and returned to his vehicle to call for assistance, seek better cover, and possibly have access to a better weapon (like a shotgun), he would have been in a better tactical position to fight, if Manning and Williams had decided to attack while he waited for backup.26

Either of these options to temporarily withdraw would have given Trooper Lamonaco time, distance, resources, and opportunities that he voluntarily surrendered when he chose to remove Manning from the car and disarm him, by himself;

-

- Arrest and Control. We’re given to understand that Trooper Lamonaco chose to remove Manning from the car, disarm him, and place him against the suspect’s car for an additional search and handcuffing, while Williams remained inside.

This procedure was destined to overwhelm Trooper Lamonaco and make it impossible to monitor and control Williams, as he handled Manning. As we discussed, it may have been better to conduct a tactical withdrawal, and wait to disarm and hook Manning until backup arrived, but even if the circumstances led Trooper Lamonaco to believe that he needed to disarm Manning immediately, there were other tactics he could have used to enhance his safety.

Lamonaco could have shifted to a one-man version of a high risk stop, returned to his patrol car, and commanded Manning to exit his vehicle and move back to the patrol car for disarming, searching, and cuffing. This would have given him a reactionary gap to deal with Williams, if Williams chose to exit the car, shooting. It would also have given him some useful cover and concealment to fight from. If Manning failed to comply with the commands, it would have been very clear to Lamonaco that he needed additional help, and he would have been in the best tactical position to deal with the suspects as he waited for it.

Alternatively, Lamonaco could have disarmed Manning after he exited, immediately ordered him to his knees with his hands on his head, then moved back to his patrol car, to monitor both Manning and Williams from a distance, as he called for help. There was no need to spend the extra time “in the hole” with Manning, at the driver’s door, to search and cuff him alone, especially since Williams was just feet away, and could not be seen or monitored by Lamonaco as he stood outside the vehicle, dealing with Manning.

It’s also suggested that if Manning had been disarmed first, then immediately cuffed, then searched more thoroughly after he was cuffed, it would have simplified things for Trooper Lamonaco when Williams came out shooting. When Williams popped out of the car, Manning was still being searched and had his hands free. He was able to shove Lamonaco to the ground, which put the trooper in a terrible tactical position—unable to move “off the X,” unable to draw his weapon quickly, and unable to get into the fight. By the time Lamonaco was able to get up, start moving, and start shooting, he was already being fired upon by Williams, and had possibly been struck several times by Williams’ gunfire. To make matters worse, he had to split his attention between Williams and Manning, who was still loose and still a threat.

Had Manning been handcuffed first, after his weapon was taken away, and then subjected to a more thorough search, Trooper Lamonaco would have been in a better position to respond when Williams came out shooting. He may not have been pushed to the ground, and he may have been able to focus on Williams more exclusively. As a result, Trooper Lamonaco might have been able to land a better hit on Williams, before he was mortally wounded, himself.

A NOTE ABOUT CAPACITY

Because it was claimed that Trooper Lamonaco was outgunned by an attacker whose weapon held more rounds, it’s necessary to take a harder look at this element of the shooting.

The truth is that there’s insufficient evidence that ammunition capacity was a factor in Trooper Lamonaco’s death. It’s true that Trooper Lamonaco fired all his rounds without stopping his attacker, but it’s not clear whether additional rounds in the gun would have saved him.

Recall that Trooper Lamonaco had already been shot and driven to the ground by Williams’ gunfire, when Williams fired the final rounds of the shootout. Investigators suspected that Trooper Lamonaco was driven to the ground by three hits to his chest that were stopped by his vest, and Williams then took the opportunity to fire the two killing shots that struck in areas unprotected by the vest.

It’s not clear that Trooper Lamonaco could have continued firing, even if his gun still contained ammunition, after falling and taking the fatal round through his left armpit. We can’t dismiss the possibility outright, but it seems speculative, at best, to claim that Trooper Lamonaco was jeopardized by a weapon that only held six rounds. It’s just as likely that he only fired six rounds because he ran out of time before he could fire more. Had he been armed with a semiautomatic pistol, he may have died with six of his casings on the deck, and ammunition still left in his gun.

It’s helpful that the appellate court record of defendant Thomas Manning indicates that Trooper Lamonaco had a fully-loaded, five-shot, .38 Special Smith & Wesson revolver on his person. This seems to reinforce the argument that Trooper Lamonaco was no longer physically capable of firing additional rounds after he expended his first six. If he’d been capable of continuing the fight, he certainly would have gone for that backup gun when his service weapon ran dry.27

Regrettably, and most importantly, while Trooper Lamonaco had the time to fire six rounds, none were delivered with the level of precision necessary to stop his attacker. This was likely the result of a rushed or panicked mental state, generated by the close range ambush. It’s common in these surprise ambushes for officers to rapidly fire a salvo of “get off me” rounds, as they attempt to “catch up” from their tactical and mental deficit, but this kind of shooting rarely produces the desired results.

The suspect definitely has an advantage in an ambush, as he is several steps ahead of the officer’s OODA cycle, but the best way to interrupt his plans and “reset” the cycle in the officer’s favor, is to deliver accurate hits on target. We recognize this is easy to say from the safety and comfort of hindsight, and much harder to do in the moment, but there’s no changing the fact that what Trooper Lamonaco needed to do was make one good, deliberate shot, instead of firing six fast shots that missed their mark. There’s nothing to indicate that having more ammunition on tap would have allowed him to do that—his critical resource was time, not ammo.

This is not intended as a criticism of Trooper Lamonaco, but as an observation, and a challenge. We understand a lot more about the science of human response to stress, and the emotional, psychological, and physical reactions of humans engaged in combat, than we did in Trooper Lamonaco’s era. Police firearms training was still rudimentary in his time, and trainers didn’t have access to the knowledge we have today. Trooper Lamonaco did the best he could in a difficult situation, but there was little-to-nothing in his police firearms training that could have prepared him for the realities of the gunfight that killed him; Nothing which would have prepared him to make the kind of speedy, but “mentally unflustered” shot that frontier lawman Wyatt Earp described.

Trooper Lamonaco needed better training more than he needed additional ammo, that night. We have the knowledge and ability to deliver this kind of enhanced training today, which provides realistic experience, enhances decision making, and improves an officer’s resistance to the debilitating effects of stress, but many public safety agencies continue to use the outdated practices and methods of Trooper Lamonaco’s era. We can do better than that, and Trooper Lamonaco’s sacrifice demands it.

FORWARD!

The murder of Trooper Philip Lamonaco was an evil and wicked act that cost his family a husband, father, and son, and his agency a courageous, dedicated, hardworking trooper. The NJSP, and the community they served, were poorer for his loss.

The Lamonaco shooting was also an important milepost in the history of American law enforcement. It turned the New Jersey State Police into an early adopter of autopistols, and encouraged other agencies around the nation to follow suit. Before long, all state police and highway patrol agencies in the union would be issuing autos to their troops, as well. That makes it a notable historical event for RevolverGuys interested in this transition period.

It’s important though, to keep all the lessons of the Lamonaco shooting in our crosscheck. We can’t afford to typecast the shooting solely as a lesson about capacity, especially since the support for the argument is weak. Instead, we owe it to Trooper Lamonaco to pay attention to all the officer safety lessons that he bought and paid for with his life.

To do any less, would waste his sacrifice.

So pay attention to what you’re doing, be safe out there, and God bless you all.

*****

Note: This article was updated, post publication, on 11 July 2023, to include new information from the appellate court record of Thomas Manning.

ENDNOTES:

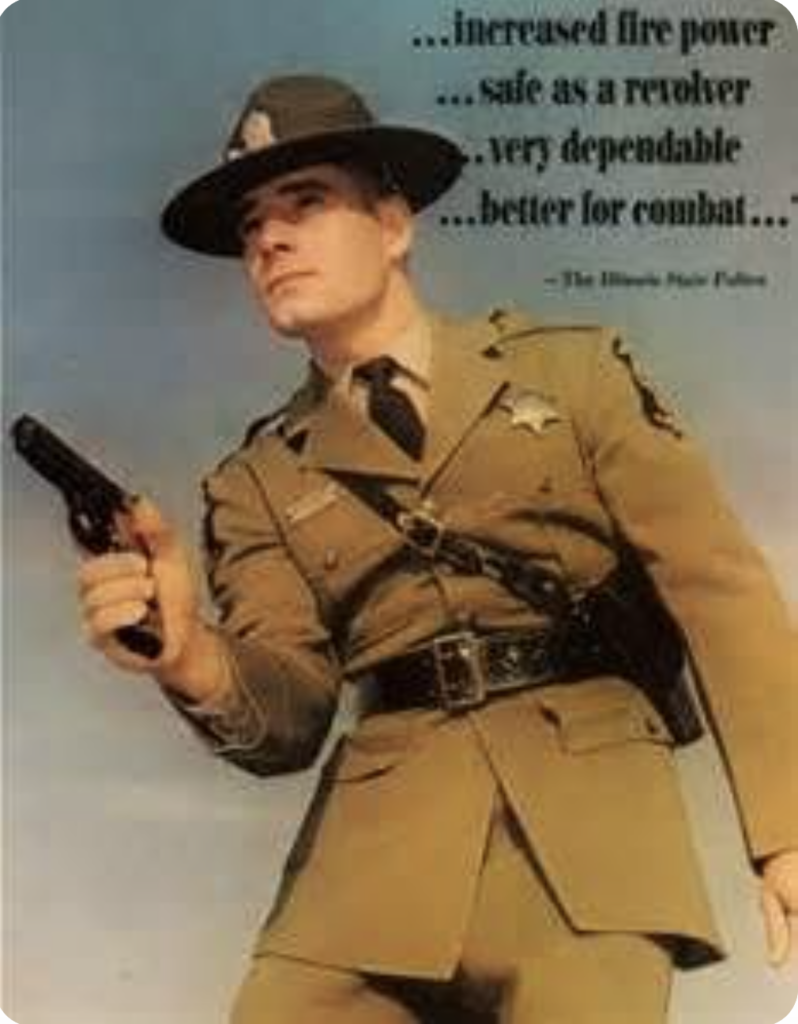

1. The Colt 1911 had seen a lot of use in Texas and the greater desert Southwest, of course, and even filled a lot of big city and federal holsters, during the 20s and 30s. It saw service in some of the county motor squads that predated the formation of the California Highway Patrol in 1929. “Old Slabsides” was also pretty popular with officers in a variety of Southern California agencies in the 60s and 70s (such as El Monte PD), at a time when the Illinois State Police was busy wringing out the Walther-inspired, S&W M39.

Some agencies, like the Salt Lake City, UT, Police Department, and Dobbs Ferry, NY, Police Department, gave the auto a try and went back to revolvers (S&W M59 to M66, in the case of Salt Lake) in the 70s and early 80s. By the early 1980s though, the autopistol train was really building a head of steam, and most agencies were clamoring for autos, not dumping them. Agencies like the Connecticut State Police (1981—Beretta 92) got the ball rolling, and many others would soon follow. Even those who had tried the auto, then returned to the revolver, were looking to try the auto again, by the close of the decade;

2. Narvaez, Alfonso A., “Why Trooper Died Despite His Vest,” The New York Times, 27 Dec 1981, and; Novak, Steve, “Remembering the N.J. Trooper Slain 25 Years Ago on I-80,” LehighValleyLive.com;

3. Hanley, Robert, “Highly Decorated Jersey Trooper Slain on I-80,” The New York Times, 22 Dec 1981, and; Website of the Office of the Attorney General, New Jersey State Police;

4. Hanley, 22 Dec 81;

5. Glading, Jo Astrid, “State Police Made Changes After Trooper’s Shooting,” AP News, 11 Jan 1987;

6. New Jersey Trooper Werner Foerster was murdered, and Trooper James Harper was wounded, by members of the radical, revolutionary, Black Liberation Army (BLA) during a traffic stop on the New Jersey Turnpike on 2 May 1973.

Trooper Harper had stopped a car with Vermont plates for speeding, which contained three BLA members—a male driver (Clark Squire), a male back seat passenger (Zayd Shakur), and a female front seat passenger (Joanne Chesimard). Trooper Foerster backed up the call, to assist.

When Trooper Harper noted a discrepancy with the registration provided by the driver, Squire, he asked him to step to the rear of the vehicle, where Trooper Foerster would interview him. As Harper continued with his investigation, Foerster found a pistol magazine on Squire. When he announced the discovery to Trooper Harper, Chesimard used the distraction to draw her own pistol, and shoot Trooper Harper in the shoulder. Harper drew his own gun, shot both Chesimard and Shakur inside the car, then stumbled away.

Meanwhile, in the chaos, Squire produced his own gun, and shot Trooper Foerster with it. When the autopistol jammed, he overpowered Trooper Foerster, took his revolver, and shot him in the head with it twice, killing him immediately.

Trooper Harper ran for the Turnpike Authority building (which was also the local State Police Barracks), located two hundred yards to the south, as the three BLA members drove off. Squire ditched the car five miles south of the scene, on the side of the turnpike, and ran off into the woods, where he was captured the next day. Chesimard was found beside the car, bleeding from a chest wound, and Shakur was found dead inside the car. Two jammed automatic pistols were recovered at the scene of the shooting.

Squire was convicted for Trooper Foerster’s murder, and was sentenced to Life in prison, in 1974. He was granted parole in 2022, at the age of 85.

Chesimard, a darling of the Radical Left, was also convicted of Trooper Foerster’s murder, and sentenced to “Life, plus 26-33 Years,” but was freed from the poorly-secured, Clinton, NJ, Reformatory For Women, in a daylight raid conducted by armed members of the BLA and other allied domestic terror groups. Chesimard eventually fled to Cuba, where she is suspected to remain, today. She is listed as one of the FBI’s Most Wanted Terrorists;

7. The terrorist group was named after two radical revolutionaries. Sam Melville was serving time in prison for eight, 1969 terror bombings in New York City when he was killed by police during the Attica (NY) Prison Riot in September 1971. Jonathan Jackson was killed by police during the courthouse kidnapping of Marin County (CA) Judge Harold Haley. Jackson was the younger brother of radical revolutionary, and Black Guerilla Family founder, George Jackson, who was one of three inmates charged in the death of Soledad Prison (CA) Corrections Officer John Mills. Jonathan Jackson and two accomplices kidnapped Judge Haley and held him hostage (along with a deputy district attorney and three jurors), demanding the release of George Jackson and the other two “Soledad Brothers” suspected of killing Corrections Officer Mills. Jackson, the accomplices, and the judge were all killed when the kidnappers tried to drive away from the courthouse with their hostages.

Estimates of the group’s terror activities vary. A Wikipedia entry claims 20 bombings and 9 bank robberies. The New Jersey State Police website estimates the group was responsible for “eighteen bombings and numerous bank robberies,” while a University of Pennsylvania study says the group was “accused of nineteen bombings and attempted bombings, plus ten bank robberies.” No matter how you slice it, the group was highly active in its nine years of existence. (Burrough, Bryan, Days of Rage, Penguin Books, 2015, and; Office of the Attorney General, New Jersey State Police, and; University of Pennsylvania, Case-Study of U.S. Domestic Terrorism, The United Freedom Front);

8. In the aftermath of the shooting, both Manning and Williams insisted that Williams was not present. Manning claimed to have dropped him off at a rest stop, prior to the shooting, but law enforcement and the prosecution team were sure, based on fingerprints, bloodstains, and other evidence, that Williams had been in the car when it was stopped. Manning’s own associates would later tell journalists that they believed Manning was just covering for Williams with his story—possibly to protect him from his fellow SMJJU terrorists, as Williams was increasingly viewed as an unacceptable liability, due to his problematic heroin addiction. The addiction put a financial strain on the group, made Williams an untrustworthy, operational risk, and brought undue attention to the “underground” group that was desperately trying to maintain its false cover. (Burrough, Bryan, Days of Rage, Penguin Books, 2015, p.518, and; Novak);

9. Hanley, 22 Dec 81, and; Unknown author, “Radical Link Probed in Trooper Slayings,” The Morning Call, 13 May 1984

10. Officer Down Memorial Page website, and; The FBI Files, “Radical Agenda,” Season 6, Episode 4, original air date 15 October 2002, and; The Morning Call, 13 May 1984;

11. Law enforcement investigators and the prosecution team would have to recreate the action from the evidence recovered at the scene, since Manning’s testimony was not entirely credible. Manning claimed he was alone that day, and had been placed against the car by Trooper Lamonaco, who searched him and soon realized that Manning was a fugitive. Manning claimed that Lamonaco began firing at him, and he reflexively pushed the trooper to the ground, rushed around the car to the passenger side, retrieved a weapon from the glove box, then began firing at Lamonaco in self-defense, killing him. Manning’s story was disproved with physical evidence that showed he was not alone, and a dash of common sense. It’s possible Lamonaco fell to the ground while moving away from Williams’ gunfire, or stumbled when he was hit, but it’s equally likely that Manning actually told the truth about pushing him down. (Unknown author, “Shooting Was a Turning Point for Radicals,” The Morning Call, 4 Jan 1987);

12. Lieutenant Richard Ryan, quoted in The FBI Files, “Radical Agenda,” and; Hanley, 22 Dec 81, and; The Morning Call, 13 May 1984;

13. Initial reports in the New York Times indicated that police believed eight rounds had been fired from Williams’ pistol, but in a subsequent interview for a television production that aired in October 2002, investigator Lt. John Mendraes (unverified spelling) stated that twelve 9mm cases were recovered from the snowbank adjacent to where the car had been parked at the time of the shooting. A newspaper story from 2006 indicated that Lamonaco had been shot a total of nine times (see Endnote #15). Investigators also found Williams’ bloodstains inside the Nova on the passenger side of the vehicle. (Officer Down Memorial Page, and; The FBI Files, “Radical Agenda,” and; Hanley, 22 Dec 81, and; Narvaez, and; Novak);

14. The vest was one of 400 purchased by the NJSP using a federal grant. The NJSP had an estimated 1,900 troopers at the time, so not every trooper had an issued vest. Early reporting indicated that some of the 9mm rounds may have penetrated through the vest, but this was later corrected–the vest worked properly, and stopped the rounds which struck its ballistic panels. (Narvaez);

15. New Jersey State Police Superintendent Colonel Clinton Pagano told reporters, “The trooper was shot and fatally wounded as he lay on the ground.” Investigators believed the rounds which impacted Lamonaco’s vest knocked him to the ground, where Williams shot him again with the bullet that penetrated through the unprotected armpit area.

The appellate court record for Thomas Manning includes the following accounting of the shots fired at Trooper Lamonaco:

According to the doctor who performed the autopsy, Lamonaco had been shot nine times, but because he was wearing a “bullet-proof” vest not all the bullets entered his body. One went through only his clothing, never touching his skin; one dented his vest and his skin at his left breast-pocket level; one struck the muscle of his right upper arm, which was not protected by the bullet proof vest; another entered his right leg just above the knee, and another entered and exited his left fourth finger, which was wrapped around his flashlight. (No witness testified to seeing a flashlight in the trooper’s hand, only a gun). The fatal bullet struck his upper left arm, then entered his chest, passed through his lung, his heart and the other lung, and exited through the right side of his chest, getting trapped between his skin and his clothing. Three other bullets had been fired in a cluster into the trooper’s back, at his right shoulder. They were fired, according to the pathologist, at the same 30-degree downward angle while the “target” was “prone” and “stationary.” The bullets were fired from a nine millimeter Browning high power semi-automatic pistol.

(Justia.com, and; Narvaez, and; Lt Richard Ryan-unverified spelling-quoted in, The FBI Files);

16. Novak;

17. Ibid;

18. Ibid, and; The FBI Files;

19. Gray, Matt, “Domestic Terrorist Convicted in Murder of N.J. State Trooper Philip Lamonaco Dies in Prison,” NJ.com, 1 August 2019, and; Novak, and; University of Pennsylvania, Case-Study of U.S. Domestic Terrorism, The United Freedom Front;

20. Glading;

21. Ibid;

22. Pagano, Colonel Clinton L., “The 9mm Auto as Police Sidearm,” The Police Marksman, January/February 1984, Volume IX—No. 1;

23. Sadly, LE-MIL organizations are renowned for their failures to preemptively support, equip, train and protect their troops. It seems there’s always energy, funds, and commitment for these things after tragedies and failures, but not before.

Another example of this trend, from the Lamonaco era, was the 9 May 1980 Norco Bank Robbery shootout, which cost the life of Riverside County (CA) Deputy James Evans, and resulted in at least 11 officers being wounded. “Norco” was instrumental in launching the law enforcement patrol rifle movement in California, encouraging multiple Southern California agencies, and even the California Highway Patrol, to adopt them (primarily Ruger Mini-14s) for patrol use. The urban chaos of the preceding decades had long ago demonstrated the need for rifles in patrol cars, but it took Deputy Evans’ death to turn it into a reality for many SoCal agencies.

The effort didn’t gain significant national traction though, until the 28 February 1997 North Hollywood Bank shootout, which resulted in dozens of injured officers and citizens. In the wake of this televised, high-profile shootout, agencies all over the United States finally clamored for rifles. Many agencies received “free” M-16 rifles through the DoD’s 1033 program, but most simply purchased or approved AR-pattern rifles. Many of the early, Mini-14-equipped departments upgraded to the AR platform during this period, as well.

The officers of the Los Angeles Police Department used the North Hollywood opportunity to successfully lobby for both patrol rifles, and a long-delayed authorization to carry .45 ACP pistols on patrol, which had previously been denied by department and civic leaders. The .45s would have made no difference in North Hollywood, but the officers, like their NJSP brethren in 1982, realized they had to make their move while the momentum had temporarily shifted, in their favor;

24. Just a few months before the Lamonaco murder, members of a domestic terror group that combined elements of the Black Liberation Army and Weather Underground Organization killed two police officers and one Brinks armored car guard, and wounded two guards and one officer, using shotguns and automatic weapons (M-16 rifles) in New York. Seven weeks after the Lamonaco murder, another member of the SMJJU (or United Freedom Front, as they rebranded themselves) engaged Massachusetts State Troopers Michael Crosby and Paul Landry in another shootout, while armed with a 9mm semiautomatic pistol.

For a period, the officers in the greater New England area had good reason to believe they were under assault from an army of domestic terrorists armed with increased capacity weapons. Other events from around the nation echoed the theme, such as the May 1980 Norco Bank Robbery, involving automatic weapons and explosives, and a host of 60s and 70s-era engagements with various revolutionary groups like the Black Panthers, Symbionese Liberation Army, Black Liberation Army, and others, who used explosives and automatic weapons in their attacks on police.

As part of their autopistol study, the NJSP reviewed data from the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Reports on Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA). According to the NJSP, the FBI LEOKA data for 1980-1982 indicated:

. . . the incidents of officers killed with 9mm handguns has increased 200 percent. This increase has occurred at a time when the data not only demonstrated a corresponding 50 percent decrease in the use of .38 caliber revolvers, and a 37 percent decrease in the use of .357 Magnum revolvers, but more importantly, reflected a 17 percent decrease in the total figure for officers killed by means of handguns. Such a dramatic escalation of the use of the 9mm’s further enhances the reliability of reports from intelligence sources indicating the exclusive use of such weaponry by terrorist groups . . .

Aside from the apparent pattern established by terror groups, the drug wars of the 1980s were already in full swing as well, bringing heavily-armed drug traffickers in contact with police forces that were still predominantly armed with revolvers. (Pagano);

25. Indeed, it appears the NJSP later came to the same conclusion, and changed their policy for calling in vehicle stops. At the time of the Lamonaco shooting, troopers were only required to report vehicle stops conducted at night, but in the wake of Lamonaco’s death, troopers would now be required to call in vehicle stops made during daylight hours, as well. (Hanley, Robert, “Manhunt Still Intense in ‘81 Slaying,” The New York Times, 21 Dec 1983);

26. It appears that Trooper Lamonaco did not have access to a shotgun, since NJSP cars were not equipped with them, yet. The NJSP Weapons Committee was established in 1982, at the direction of the Superintendent, in response to the Lamonaco shooting. The Committee’s work led to adoption of the HK P7M8 pistol, and also led to placing shotguns in Troop cars (Remington 870s).

Interestingly, the California Highway Patrol (CHP) had taken the same path, almost twenty years before. The CHP didn’t begin to issue shotguns to their officers until Officer Glenn Carlson was killed by shotgun-toting bank robbers, on a traffic stop in 1963. After Carlson’s death, a state senator pushed the CHP into putting shotguns in patrol cars. The CHP was hesitant, and only equipped a portion of the fleet at first, but the 1965 Watts Riot accelerated the process, and soon, every CHP patrol car was equipped with a Remington 870.

Even though Trooper Lamonaco didn’t have had access to a better weapon back at his car, retreating to the vehicle still would have offered him substantial cover, access to the police radio, and an improved reactionary gap. These factors would have made it a better course of action, than dealing with Manning at the driver’s door. (Office of the Attorney General, New Jersey State Police)

27. Thanks to RevolverGuy reader James Ferris for providing the information and link! (Justia.com)

REFERENCES

Books:

Brooks, Pierce R., Officer Down, Code Three, Motorola Teleprograms, Inc., 1975, pp. 171-3;

Burrough, Bryan, Days of Rage, Penguin Books, 2015, pp. 246-48, 518-21, 523, 544.

Magazine Articles:

Pagano, Colonel Clinton L., “The 9mm Auto As Police Sidearm,” The Police Marksman, January/February 1984, Volume IX—No. 1.

Newspaper Articles:

Glading, Jo Astrid, “State Police Made Changes After Trooper’s Shooting,” AP News, 11 Jan 1987, located at: https://apnews.com/article/4c1bbe998d14bfce6dda3c9511049cc1 ;

Gray, Matt, “Domestic Terrorist Convicted in Murder of N.J. State Trooper Philip Lamonaco Dies in Prison,” NJ.com, 1 August 2019, located at: https://www.nj.com/warren/2019/08/domestic-terrorist-convicted-in-murder-of-nj-state-trooper-philip-lamonaco-dies-in-prison.html ;

Hanley, Robert, “Highly Decorated Jersey Trooper Slain on I-80,” The New York Times, 22 Dec 1981, located at: https://www.nytimes.com/1981/12/22/nyregion/highly-decorated-state-tropper-slain-on-i-80.html ;

Hanley, Robert, “Manhunt Still Intense in ‘81 Slaying,” The New York Times, 21 Dec 1983, located at: https://www.nytimes.com/1983/12/21/nyregion/manhunt-still-intense-in-81-slaying.html ;

Hill, Amy Hearth, “Police Turning to 9mm Guns to Fight Crime,” The New York Times, 12 Mar 1989, located at: https://www.nytimes.com/1989/03/12/nyregion/police-turning-to-9-mm-guns-to-fight-crime.html ;

Johnson, Richard J. H., “Squire Sentenced to Life for Killing State Trooper,” The New York Times, 16 March 1974, located at: https://www.nytimes.com/1974/03/16/archives/squire-sentenced-to-life-forkilling-state-trooper-special-to-the.html ;

Johnston, Richard J., “Trooper Recalls Shooting on Pike,” The New York Times, p. 86, 14 February 1974, located at: https://www.nytimes.com/1974/02/14/archives/trooper-recalls-shooting-on-pike-testifies-squire-was-in-car-with.html ;

Narvaez, Alfonso A., “Why Trooper Died Despite His Vest,” The New York Times, 27 Dec 1981, located at: https://www.nytimes.com/1981/12/27/nyregion/why-trooper-died-despite-his-vest.html ;

Novak, Steve, “Remembering the N.J. Trooper Slain 25 Years Ago on I-80,” LehighValleyLive.com, located at: https://www.lehighvalleylive.com/warren-county/2016/12/35_years_trooper_killed_on_i-8.html ;

Sullivan, Joseph F., “Panther, Trooper Slain in Shoot-Out,” The New York Times, p.1., 3 May 1973, located at: https://www.nytimes.com/1973/05/03/archives/panther-trooper-slain-in-shootout-woman-sought-in-killing-of.html ;

Unknown author, “Radical Link Probed in Trooper Slayings,” The Morning Call, 13 May 1984, located at: https://www.mcall.com/news/mc-xpm-1984-05-13-2414162-story.html ;

Unknown author, “Shooting Was Turning Point for Radicals,” The Morning Call, 4 Jan 1987, located at: https://www.mcall.com/news/mc-xpm-1987-01-04-2569398-story.html ;

Waggoner, Walter H., “Jury in Chesimard Murder Trial Listens to State Police Radio Tapes,” The New York Times, p.83, 14 February 1977, located at: https://www.nytimes.com/1977/02/17/archives/jury-in-chesimard-murder-trail-listens-to-state-police-radio-tapes.html ;

Videos:

The FBI Files, Season 6, Episode 4, “Radical Agenda,” Original Air Date 15 October 2002, located at: https://youtu.be/lAoI07dVzv4 ;

Websites and Online Resources:

Federal Bureau of Investigation, Most Wanted, Most Wanted Terrorists, located at: https://www.fbi.gov/wanted/wanted_terrorists/joanne-deborah-chesimard

Justia.com, State v. Manning, 234 N.J. Super. 147 (1989), located at: https://law.justia.com/cases/new-jersey/appellate-division-published/1989/234-n-j-super-147-0.html

Office of the Attorney General, New Jersey State Police, located at: https://www.nj.gov/njsp/trooper-of-year/1970s.shtml

And:

https://www.nj.gov/njsp/about/history/1980s.shtml

Officer Down Memorial Page, located at: https://www.odmp.org/officer/7835-trooper-ii-philip-joseph-lamonaco

University of Pennsylvania, Case-Study of U.S. Domestic Terrorism, The United Freedom Front, located at: https://www.personal.psu.edu/faculty/j/p/jpj1/uff.htm

Thanks Mike, for an excellent article. I can not wait for the second installment.

As far as someone taking exception to the analysis of the incident I don’t think that would happen. Of course there are those few who look for anything to take exception to.

A critical analysis of an OIS is no different than studying any type of loss or tragedy with the perpetual effort to improve human safety. Air craft , automobile , sports, medical practices and many other areas of life that sometimes results in death all benefit from after event study.

Thank God for the folks who study these events with the aim of preventing them when and where possible.

Thank you Sir, much appreciated. The only way we learn and advance is by asking hard questions and being free to discuss them.

Mike,

What a chilling account!

There are clearly lessons learned here… all officers in Ohio are taught to call in their stops immediately, and to cuff then search. I’m sure that’s true most other states too.

As far as equipment, I would still carry a revolver as a duty weapon, another for backup(NY reload in this case), if allowed. Since I’m not, I carry a Sig P365XL as backup to my M&P (common caliber). It’ll do.

I wonder if you could tell me what ammunition Trooper Lamonaco was using, and where Williams was hit? If issued .38 special, maybe a magnum load would have fared better, particularly through window glass… but nothing is guaranteed of course.

As always, thank you for enlightening us.

Thanks Riley. He was shooting Win .38 Spl. 110 +P, which doesn’t do that great through a windshield. I did my best to learn more about Williams’ wounds but couldn’t find any info. I believe they were minor, possibly just from frag.

I was actually frustrated by the lack of good information on this shooting, and my sources came up dry, and couldn’t help. I have many questions I’d like answered, but had to do the best I could with the info I had available. If a reader has better info, or a better source, I hope they’ll reach out. I reserve the right to be corrected, pending better info!

Thank you, Mike, for a superbly detailed examination of a tragic event. Much like Newhall, in hindsight, fatal mistakes were made, yet in so many cases, the lessons were quickly covered over by other agendas, in this case the desire for autoloading pistols.

It is interesting to note that even at that late date, NJSP did not seem to make use of the portable repeater radio such as the Motorola HT-220. We had those coming into use in the late 1970s after an agency wide shift from HF to VHF and later UHF radio frequencies. Yet even with portable radios, dispatch did not know where we were unless we advised them.

I can attest that all it takes is one close call to realize you ain’t John Wayne, and you definitely ain’t RoboCop, and Adam-12 was a pipe dream. ( In the South, ain’t is short for aresn’t … like t’aint is short for that is not ).

LEOs today have SO many more coms at their disposal, from mobile GPS tracking to portable radio and telecom, to video and computer terminals in the cars. There should never be a ‘Car 54 Where Are You?’ event in daily LE operations.

Guys – watch your 3-6-9 as well as 12, and always call in any contacts you make.

Thank you Sir, I appreciate the solid advice from someone who’s been there, done that.

Hubris, and other failings, can cloud the judgment of more than police officers while in dangerous situations. The terrible event described in this article also has lessons for citizens, especially those who legally possess firearms.

When reading articles about people who employ guns to defend themselves and others, a common fault I’ve noticed is when someone (e.g., the “good guy”) choses to leave a place of safety (i.e., a house, workplace, vehicle) to confront a criminal, often with dire results for the citizen.

Thanks Spencer. While the article is definitely more LE-focused than most RevolverGuy fare, there’s still plenty of valuable lessons in it for good guys who don’t carry badges. I thought that made it a good fit.

Once again, this site remains a top source of firearms information,

particularly revolvers, than any other. Always factual, informative

and needed in the discussion of firearms.

And this article helps clarify some notions in the sometimes silly

debate of auto vs. revolver. Thank you!

Thanks Mike, for the detailed analysis on Trooper Lamonaco’s incident. Your study and observations help keep his sacrifice meaningful and relevant for another generation of officers around the country. God bless his family, especially his son Sergeant First Class Lamonaco- who chose to follow in his father’s footsteps.

Thank you Sir! I sure hope it helps somebody out there, in uniform. God bless them all!

You know, it occurs to me that “tombstone courage” kind of falls in with cop personalities. We are, many of us, thrill seekers. I myself was a paratrooper and still love roller coasters.

There’s no doubt that the profession often attracts a certain kind of personality. It was the same in the military, and that’s honestly a good thing—you couldn’t do the job well without it.

“The thrill of it” is what attracted most of us to flying, and particularly military flying. Along the way to becoming a professional airman, though, you begin to realize that the job is about managing risk. You accept that risk will always be a part of it, and you do your best to mitigate it, while still getting the mission done. You take on additional risk when it’s necessary to accomplish the mission, but only with consideration. You certainly don’t act recklessly or haphazardly, because that only jeopardizes the mission, the people you work with, and the equipment you’re responsible for.

That doesn’t mean you don’t appreciate the thrill of it. We’ve all got a bit of adrenalin junkie in us, but we strive not to let it cloud our judgement, and encourage us to be reckless.

I know the same concepts apply to our LE brothers. You can’t run from risk in that job, but it pays to avoid unnecessary risk. There will always be enough thrills that naturally come with the territory—no need to chase them, if you want to grow old!

Great article. I have one of the same vintage belts these officers are wearing in those photographs though without the chest strap. I wonder if it would be worth anything or if anyone would be interested in it?

Mike, thank you for the article.

America suffers from weak prosecution of some violent criminals, weak support for law enforcement in some jurisdictions, and weak application of serving full sentences for crimes committed by some violent criminals.

My “weak” and “some” serve only to not condemn all in one stroke. However, weaknesses in criminal apprehension, aggressive prosecution, and full no-slack punishment gets innocent civilians and police officers injured, crippled, or killed far too often.

Troopers Philip Lamonaco and Werner Foerster might be alive today if the career criminals encountered in their final stops had stayed locked up for crimes committed prior to killing two New Jersey law enforcement officers.

Amen, brother, and it’s only getting worse. This can’t last much longer, though. Americans are starting to realize that soft-on-crime policies are ruining their communities, and I’m hopeful they will start kicking these weak DAs out of office, and change these weak and destructive policies on bail, sentencing, etc.

Are you going to discuss that, even though Trooper Lamonaco was carrying over thirty rounds of spare ammo, they were in individual leather loops? Those would make for the slowest method of reloading that there was. Speed loaders existed at the time. Even a dump pouch would have been faster.

Thanks Misfit. That was certainly a poor setup, but since he never got the opportunity to reload, it had no bearing on the fight and I didn’t feel the need to address it.

There was no excuse for any agency to mandate loops at that late date, eleven-plus years after Newhall, but as we’ll see in the next story to follow, NJSP certainly wasn’t alone in that regard. There was actually a shocking number of agencies that kept dump pouches and loops (I’d rather have those than the dump pouches, myself) until switching to autos. As I discussed in the story, there’s always money available to fund improvements after tragedy strikes, but institutional inertia can be difficult to overcome, prior to that.

The troopers definitely improved their lot, from the standpoint of capacity and rapid reloads, with the P7M8.

(This is kind of a remake of a comment I made a few days ago, that seems to have never reached you, plus a few more observations.)

One of the reasons for the slow adoption of autopistols was the fact that in the 80s, the 9mm had a very poor reputation as an assailant-stopper. (The 9mm round the Illinois SP adopted in 1967 was a FMJ and was chosen for its good penetration through auto bodies.) Back in the 80s, every LEO in the country heard (usually third- or fourth-hand) stories about 9mm rounds not stopping offenders. The 1980 Calibre Press book “Street Survival” had a photo of a deceased offender who had been shot with 33 9mm rounds by Cook County, IL, officers. and the failure of the Winchester Silvertip in the 1986 Miami FBI shootout didn’t help the 9mm’s reputation any. It wasn’t till the 90s that more reliably-expanding 9mm bullets were common enough that the caliber caught on as a viable LE round.

Regarding the loops on the holsters: They were there because they looked cool. The people who run paramilitary organizations get fascinated by uniforms, and when they find something that strikes their fancy, they stick with it, no matter the consequences. Retired LAPD SWAT officer Scott Reitz, in his “Uncle Scotty Stories” series of Youtube videos, states that LAPD forbade speedloaders for its uniformed officers for years because sergeants wanted to look down a line of officers at attention and not see any bulges blocking their view of the whole line. Not sure if it’s true, but my experience with bureaucracies and the idiots who run them certainly doesn’t make me disbelieve it. (By the way, “Uncle Scotty” tells some great stories.)

Thanks 1811! Your first comment is a little lower in the stack, I think. Look down below—is that it?

Yes, it is. Sometimes when I visit your site I don’t get the whole comment section. Just now I originally got “18 comments” and after I rewrote my original, I revisited your site and got all 30 comments (at the time). I don’t know if this only happens to me or if it happens to others, too. In either case, I blame climate change.

Hah! I’ll buy that.

In regards to carriage of extra ammunition and department idiocy:

Illinois didn’t provide for carrying extra magazines for the first few years of the Model 39. Pistols were issued with the two that came in the box and no more. (That was common for agencies issuing the 39 and 59.) That second magazine often rode in the ash tray. A single open magazine pouch was added to the back of the holster flap in the early 70’s.

Upon the adoption of a special Safariland border patrol holster in about 1976, no magazine pouches were provided. Troopers were not even allowed to buy their own. Back again to pockets and ash trays.

Uniformity above all else.

That went on until a 1980 firefight documented by Ayoob where a trooper wearing an unauthorized magazine pouch saved the day.

Thank you Sir, GREAT to see you here in the comments!

That kind of silliness continues, to one degree or another. A few years ago, I had some students who were police officers for a public school system in SoCal who were prohibited from carrying any more magazines than the three pistol mags issued by their department (one in the gun and two in the pouch). They were likewise prohibited from carrying any spare mags for their patrol rifles—only the single magazine in the long gun was allowed. The reason? Appearance and uniformity.

We had been discussing the idea of having an Active Shooter “Go Bag” with extra ammo and first aid gear, when they explained department policies prohibited from carrying the extra ammo. I’m sure the administrators liked the idea, but they probably didn’t think it through before issuing the decree.

I was going to make substantially the same comments regarding Illinois SP’s extra-mag policy, but my posts were already too long. Another piece of ISP bureaucratic idiocy in action: In the 70s, Illinois troopers didn’t wear dedicated gunbelts; their holsters were on their pant belts. They also didn’t have cuff cases; their cuffs were just stuck down between their belts and their pants, with the second cuff hanging outside. I remember in the early 80s seeing Illinois troopers for the first time wearing overbelts with keepers, and their holsters, mag pouches (finally!), and cuffs in cases. (All the leather was patent leather (Cordovan?) that shone like a mirror; no using darkness for concealment in the ISP!) (I think they went full-belt-and-cuff-cases when they switched to the 59-series pistols.)

One of the things to remember about the slow change from revolvers to autos is that in the 80s, the 9mm had a very poor reputation for stopping assailants. In fact, the Illinois SP’s original duty round was a FMJ, which was picked because of its better penetration through automobile bodies. The first 9mm JHPs that were issued to LE, like the Winchester Silvertip and the Remington 115-grain JHP, were not well received, especially after the Silvertip’s well-known failure in the 1986 Miami FBI shootout. The Silvertip also suffered at least one failure in an Illinois SP shooting at about the same time. It wasn’t till the 90s that more modern designs gave the 9mm the reputation that it has today. (Although to be fair, the original Silvertip appears to have been better than its reputation.)

The Illinois Silvertip failure [if it was that] was in 1980, and then the lack of penetration – from a round designed for minimal penetration – was the issue.

Illinois satisfactorily used other brands of hollow point 9 mm before and after. The WW +P+ 115 gr. JHP came in about 1985.

It’s also a myth that the original WW 100 grain FMJ was picked for penetration. The light bullet at high velocity was touted for its stopping power with less penetration and a shorter danger zone. Avoiding the anti-police “Dum Dum” attacks of the time was surely an unstated reason for the adoption of a FMJ bullet.

Yes Sir, that was absolutely a big concern for police administrators and the next article in this series will explore that a bit more (consider that a preview of coming attractions!).

Re: the Silvertip, that bullet did exactly what it was designed to do, and I always thought it got a bit of a bum rap. The Relative Incapacitation Index study promoted by the NIJ LEAA (see Here and Here) encouraged the development and use of lightweight, fast, shallow-penetrating bullets, and the Silvertip was considered one of the best in that arena. Unfortunately, there were occasions where this “ideal” police bullet was less than ideal for the circumstances, and good guys were killed. Regrettable, but not the bullet’s fault.

Yep. The later 9mm ammo that the ISP used was pretty good. My Federal agency issued the ISP +P+ rounds in the 80s. It was kind of funny, because the box read: “Not for Retail Sale. For Illinois State Police use only.” I think WW’s lawyers had a hand in that.

I read that the FMJ bullet was picked for its auto body penetration in a source I trusted, so that’s why I said it. If you have different information, I’m not gonna contradict. I well remember the “dum-dum bullet” controversies (I should say “nonsense”) in that era, and the various ways agencies tried not to get tarred with that brush. In the late 70s my own agency issued JSPs instead of JHPs for its agents who carried .357s.

I was told by an ISP pistol instructor that the reason ISP went to the Glock around 2000 was that the +P+ rounds shot the 5900-series Smiths apart fairly quickly. Again, don’t know if it’s true.

I’m just a mutt but knew many fine troopers and a couple of good brick agents. We’re all friends here.

..

Penetration was a factor considered in the choice of bullet for the 9 mm according to the “white paper” ISP put out for other agencies and published in Law & Order, et.al. but not in the sense of wanting more penetration than what they had before.

.

=================================================

.

We further decided that any weapon not capable of delivering a bullet with foot-pounds of energy approximately 400 F.P.E. [Foot-Pound Energy] to the “right address” would not be a satisfactory service weapon.

.

This foot-pound energy, we felt was a “must,” so an attempt was made to utilize a medium size 4-inch [102- millimeter] revolver by lightening the projectile and lessening the recoil. To do this, it was necessary to increase the velocity for compensation.

.

4. Lighter bullet weight (100 gr.) permits more velocity (1380 feet per second [420.6 meters per second]) within working ranges (100 yards [91.4 meters] or less), then loses speed and range rapidly, and further reduces extreme ranges (¾ mile [1.2 kilometer]) and dangerous richochets. Thus, it is safer than the 158 or 200 grain .38 Special service loads (900 F.P.S.) with one and one-half mile [2.4-kilometer] range.

.

5. Due to the light jacketed bullet at high speed, penetration through auto bodies, seats, and rubber tires is comparable to the .357 Magnum. Yet, the 9 mm with 385 foot pounds of energy will only penetrate eight inches [203.2 millimeters] of flesh.

………

The full report is included in Allen P. Bristow’s The Search for an Effective Police Handgun with is available free at archive.org.

.

For sure, the 9 mm Smith’s were worn out by the end.

If you and I are talking about the same incident, the offender was a biker who was wearing a leather jacket and heavy clothes under it (it was wintertime), the hollowpoints filled with leather and cloth and didn’t expand, and the bullets acted like FMJs and just carved tunnels. The story I heard about it for years was that the rounds expanded too soon and didn’t go deep enough, so 9mm is crap, so there! It wasn’t till I read the Ayoob article that I learned what seems to be the real story, and it makes sense, since JHPs are still known to sometimes fill up with clothing and not expand.

I’m directing this at “cm smith,” since he (she?) seems to have close ties to the Illinois State Police, and may even be a retired trooper:

All my criticisms here are directed at bureaucrats and their policies, and nobody else. In the 30 years I worked Federal LE in the Chicago area I worked with a lot of Illinois troopers, from road troops to special agents to a major, and you’d have to go pretty far to find a more professional group of people. They were always a pleasure to work with, and I can’t speak highly enough of them. It’s some of their bosses that were idiots. (We never had such problems in the G; all our bosses were geniuses. Just ask them.)

Thanks 1811. Yes, the 9mm has certainly benefited from advances in engineering, technology, and manufacture. The older JSP and JHP duty ammo of the 60s – 80s was not nearly as capable as today’s duty ammo, and there were legitimate reasons to be a little skeptical of it. The guns were certainly part of that equation too—it took a few decades to really debug the S&W 39 and 59-series guns, and cops of the era had good reason to put more faith in their revolvers. The guns and the ammo eventually got much better, but in the meantime, the reliability and performance of the revolvers (and their ammo) kept them in the mix.

If I can ever catch up on RevolverGuy, I might actually have some time to finish my Miami book, which will discuss this in greater detail.

Good job, great article.

Thank you Sir!

Thanks Mike

I lived through those times 1970-80s , carried old slab sides most of the time.

And some wheel guns also, we had to provide are own weapons and gear. The brass thought I was over prepared 😉😉😉 Shotgun and HK 91 in the trunk

The books you mentioned should still be mandatory reading for all. Coppers

You would of believe the junk some guys had in their holsters.

Thanks Dave. I don’t think anyone would have poked fun at you for the extra firepower if there had been a call where it was needed! Better to have it and not need it . . .

Brooks’ book should still be mandatory reading in all police academies! It’s timeless.

Yeah, I would . . . I saw a bunch of it !!

Mike, as always…I appreciate your objective approach to these “blood lessons” which have paved the way for continued efforts to improve officer safety concerns and training over the years. These tragedies you discuss have provided profound insight and valuable lessons for guys like me to utilize in my own career to improve my personal safety, as well as, providing insight for the “why” in training. Though unfortunate for the families of the fallen, murdered LEO’s, like Trooper Lamonaco, their sacrifices have provided valuable information for those of us following in their footsteps to utilize to protect ourselves and hopefully prevent similar, life-ending mistakes. Like your “Newhall” book, I appreciate the insight provided here. Continue to stand in the gap brother!

Thank you Sir! I’m humbled by your kind words, but proud that I can contribute something meaningful to helping our LEOs stay safe. Sometimes it seems like we’re destined to repeat the same mistakes over and over, but dedicated trainers like you are the circuit breaker to interrupt that process. I’m glad I could give you some ammo for that fight.

Stay safe brother! Looking forward to seeing you in November!

Thanks for this write up! I was a young a boy in NJ at the time of Trooper Lomonico’s murder and I remember the shock in our small shore town and the Trooper on the face of every newspaper. Our town was very close knit and we knew all the cops and they wanted “autos” to protect themselves with. Just to add some background here even in the early 80s where we lived policing was very archaic and way behind the times, we were the only part of our family that moved out of NYC and we had family on the job and could see the stark differences, it was not unusual for only one PO to be working thr graveyard shift alone and if he needed backup he would request it, though dispatch, from one of a few surrounding, and also small towns, who usually only had one PO per midnight shift themselves! Additional backup could be requested from the NJSP who had a small troop near the Garden State Parkway that would take some time getting to the request for help if they weren’t busy! One town over there was a notoriously bad area of bars called San Juan Hill where a mix of 1% bikers and gang bangers would start street fights almost on schedule and it wasn’t uncommon for 4 or 5 surrounding PDs to send their 1 man patrol to back up that towns PD and would result in max maybe 4 or 5 POs plus maybe 1 or 2 Troopers to handle a couple dozen plus drunken thugs! By 1985 I was a Police Explorer in my town and we were being taught , for our own safety, those hard learned lessons and we learned about the Lamonaco murder and we still carried a Joanne Chesimards photo in our cars every shift, by 1986 our town would still routinely assign one PO on the 12-8 shift with an occasional second, due to budgets of course! I was there to see the transition from revolvers to semi’s and that department chose the S&W 4906? It was a small, compact, metal frame 9mm with a 12 round magazine and those guys would get 2 spares! Part of the problem in that area was the false sense of security even the POs had that would eventually wake them up as well. We responded to a fight call one night where there was a very large party a our two POs were quickly overtaken and were in a full knock down, drag out fight. I was in the patrol car surrounded by a bunch of drunks who tried getting to me however I just remained calm and called for backup and….no surrounding towns could back us up because their POs were also on priority calls! By the time backup came we got 2 POs from a neighboring town approximately 40 minutes later! And this was “normal” at the time and POs were expected to just take care of it when it came to dangerous/priority jobs. It was rough at times however better training came slowly and while still maintaining friends in that department I seen them transition to the Beretta 92 and their newest sidearm they received in 2013-2014 the P229! I left to join the NYC Housing Police and was part of NYCs transition from the revolver to the semi-auto with politically mandated FMJ ammo that led to the Abner Louima tragedy and then finally getting JHP duty ammo and that debacle in the NYPD….Housing recieved Glock 19s and JHP ammo a couple of years before the NYPD except for their ESU and some undercover units like SNU(street narcotics unit) and SNAG(street narcotics and guns unit) and maybe Street Crimes. I was amazed, at the time, how slow change came to police departments and I hope better change comes faster for the new guys today!

Thanks Bob! I appreciate all the background and also the sneak peek at next week’s story! I hope you’ll chime in after you read it, and let us know what you think of it.

Small town policing has always been tough, and resources have always been scarce. Sadly, things are getting worse, not better, these days. The War on Police marches on, and departments all over America are struggling to keep enough officers on the streets. I have buddies in several major agencies who routinely work their shifts with only about 30% strength, and it’s getting worse, not better. People are getting tired, injured, worn out. They’re looking to flee to other places and agencies that aren’t as screwed up, or they’re just leaving the profession entirely.

It’s not just Patrol falling apart, either. I’m seeing SWAT units and other special teams disbanded for lack of personnel and funding; Detective units so understaffed that they can’t do any investigations, as they barely have enough folks to keep up with taking the new complaints. It’s getting real dangerous out there, and I think most members of the public are oblivious to it . . . until they call for help and nobody comes. With public disorder and property crimes skyrocketing, there’s a wider net of citizens who are starting to feel the pain, but a lot of them still don’t get it, and continue to vote for the politicians, DAs, and ballot propositions that cause the problem.

Good tactics become even more important in times like this. Unfortunately, a lot of the experience is leaving the job, and the younger officers won’t have a veteran around to show them the ropes. We’ve seen this before, and the story doesn’t end good. People will get hurt. The New Newhall is approaching, fast.

I hate to say it, but the quality of new recruits is taking a nosedive, too. Agencies are so desperate to find bodies that they’re hiring lots of folks who simply aren’t qualified to do the work. We’re on the leading edge of that right now, and starting to see the results (think Tyree Nichols, in Memphis), but this will get much worse in the years ahead. Bad recruits make bad cops, and bad cops make lots of bad decisions, bad mistakes. We’re going to be dealing with the fallout from this War on Cops for decades.

Buckle up, folks. Stay frosty. Say a prayer for the good folks in uniform who are still out there, standing between Good and Evil. They need our support, more than ever.

Yes, the 2020 troubles have led to staffing shortages. Not just a bunch of experienced cops retiring or resigning, but also the absolute dearth of applicants. Any intelligent person looking to start a career will turn away from the verbal abuse and hatred that cops endure. Which gets to the heart of what you are saying: standards are lowered, to get bodies on the street. I fear for my children’s safety long after I’m gone.

Amen, brother. This is not the America I know and love. As Tony reminds us, we have a choice: Law & Order, or Anarchy. I pray we get back to the first, quickly!

If anyone needs to get a handle on what a “defund the police” city is really like, come visit where I live: Portland, Oregon. Almost everywhere you look there will be homeless camps overflowing with shiftless vagrants, huge mounds of trash and feces, shrieking crazies roaming the streets and assaulting (and sometimes murdering) citizens, dirty needles piling up in city parks and sidewalks, and open-air illicit drug markets. So, anything goes and it usually does. My plan is to become a former Portland resident.

Hang in there, brother. I know what you’re going through.

Mike, I read your Newhall book and “enjoyed” it. This is a great article about the Lamonaco/Foerster murders. Thanks for doing what you do!!

Thank you Bronze, much appreciated. Preserving this history and passing on these lessons is important. We have much to learn, by looking backwards.