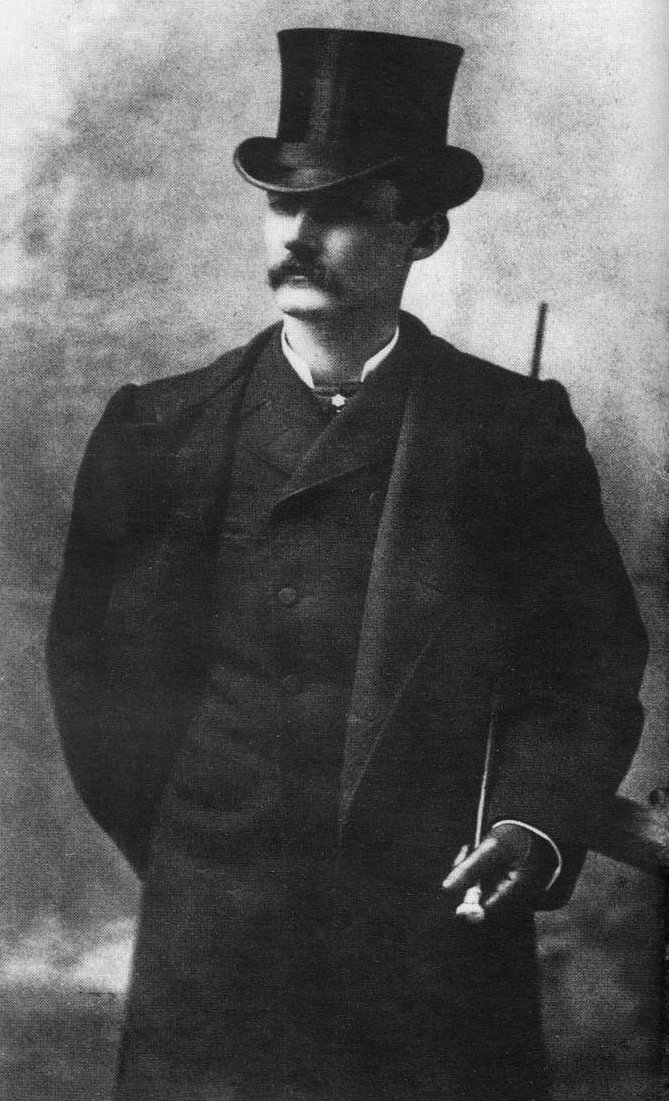

Like many Old West characters, real and imagined, the two men soon to be involved in the deadly fracas had pursued a variety of occupations, some questionable and others outright crooked. And to the casual observer, the two were physically mismatched: a dapper and diminutive fellow versus a much larger, bullying lout and a veritable Old West gangster. The bigger man had also been a marshal, ranch foreman, hitman in New Mexico, private detective and racketeer, just to name a few of his occupations. There were also rumors of his sadism, for instance, maiming opponents while serving as a lawman and ranch foreman.

About the worst that can be said about the little guy was he had been an illegal whiskey peddler to Native American tribes, a well-known gambler, saloon owner, an all-around “sporting man” with a quick eye for the main chance. He was also well-versed in “triggernometry”, having already dispatched several men who were trying to murder him. But he wasn’t by temperament a ruthless killer—unless he was sorely provoked.

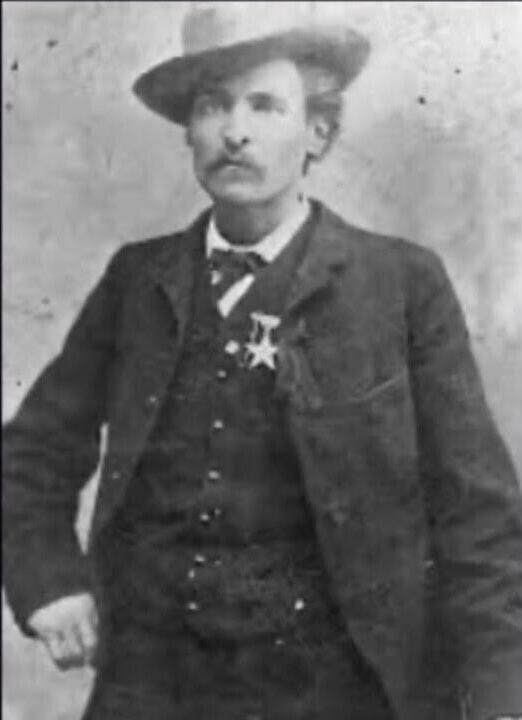

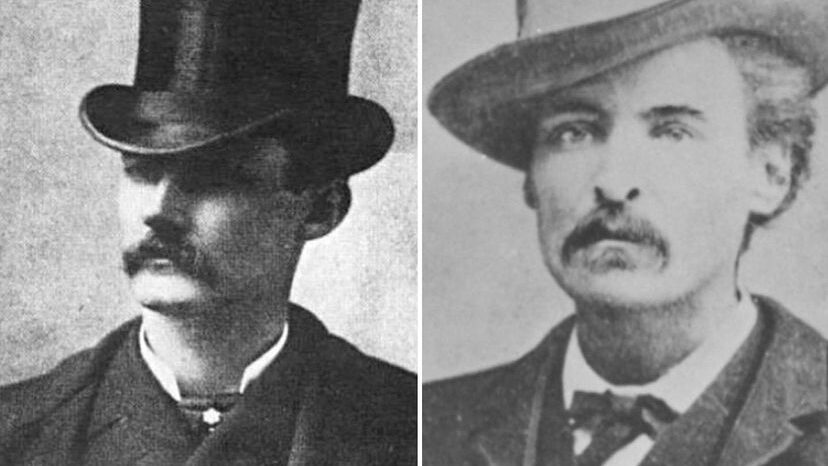

Still and all, looks can be deceiving: mild-mannered, quiet fellows sometimes can be shockingly deadly when pushed too far. The appropriately named Luke Short was such a gentleman and he didn’t mince words when menaced.1 On the other hand, his antagonist, “Long Hair” Jim Courtright seemed to revel in threatening people and flaunting his reputation as an enforcer and killer, possibly as a shake down technique.2 He also was running a protection racket scam on local businessmen. As far as lethality went, both men were experienced gunfighters and “lightning fast” on the draw.

How It Went Sideways

One night in early 1887, the preliminary terminal encounter between the dangerous pair occurred inside Luke Short’s White Elephant Saloon, situated in Fort Worth, Texas’s “dangerous Hells Half Acre”.3 For some time, Long Hair Courtright had been running his extortion scam in the city and extorting local businessmen. Readers can perhaps imagine Courtright, not so subtlety, warning his merchant prey that serious harm might come to their health or property if they didn’t cough up a financial contribution on demand. Why people didn’t band together and oppose the extortion is not clear. However, complaining to local law enforcement and courts in those days may not have helped as the authorities were often openly corrupt and took dirty money from powerful criminals like Long Hair Jim.4 It was probably thus that Courtright was getting away with his swindles.

Hence, without warning, on that night in 1887, the headstrong and venal Courtright burst into the White Elephant, confronting Short and demanding “protection money”. Because he was unwilling to be so crassly ripped off, Short replied that he didn’t need any protection and told Long Hair Jim to “go to hell.” Bully that he was, Courtright didn’t take it kindly that his smaller victim probably had mouthed off to him in front of an audience.

At this point one might wonder if Courtright was missing an unmistakable cue–the outraged smaller man was without a doubt girding himself for major-league hostilities. But Courtright had a reputation for provoking fights in public places so he could murder his opponents, believing his superior pistol skills and speed would carry him through. Strangely enough, Long Hair Jim knew of Short’s history of efficient revolver work, yet Courtright apparently thought himself the better gunman. Whatever his thoughts, Jim departed the White Elephant in a volcanic rage. Trouble of the shooting kind seemed guaranteed to follow very shortly.

Their Respective Smoke Wagons

Despite their physical differences, motives and personalities, both men went “heeled” with similar handguns: .45 single-action, six-shot Colt Peacemakers, albeit with some differences. It’s worth remembering that ammunition of that era was stoked by black powder. The standard .45 Colt cartridge then was topped off with a soft lead bullet of about 255 grains that, measured with today’s electronic devices, could clock over 900 feet per second from a revolver. Even by our modern ballistic criteria this was very respectable performance in a handgun.

Conversely, Luke Short’s carry handgun at that time was not the full-sized Peacemaker; its barrel had been cut down to snub-nose size and fitted with a gold front sight. To tote that piece, he “had his suits especially cut so that the pistol would fit, hidden, in a hip pocket and be covered by a longer vest than usual.”5 Such a concealable and powerful handgun could be jerked and fired very quickly by a practiced gun toter like Short.

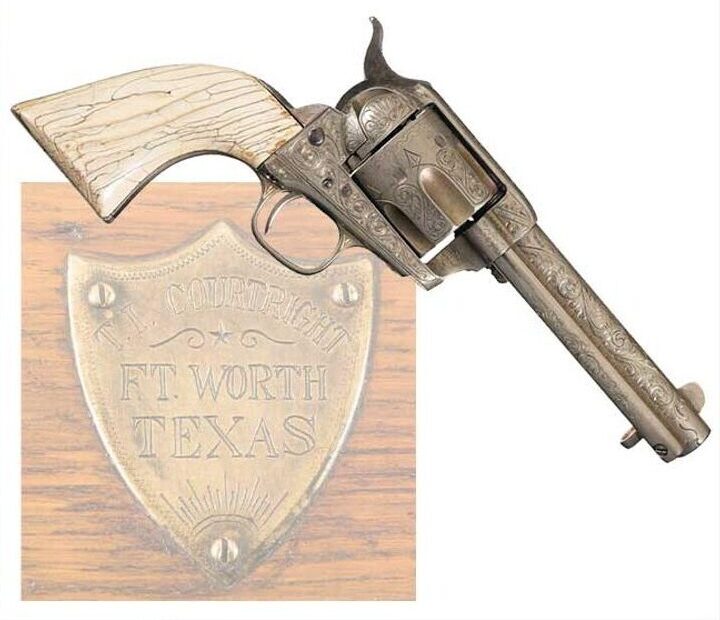

Courtright, on the other hand, apparently favored more conventionally sized Colt Peacemakers, that is, those with 4-and-3/4-inch barrels. But if the example depicted below is one of the pair that he carried late in life they were heavily engraved, apparently silver plated and sported ivory grips. Nonetheless, that size Colt would have been much easier to draw from a holster or special pocket than the standard longer-barreled model. Giving himself an extra edge, Jim carried his Colts “butts forward” either in holsters, pockets or a sash, depending on his mood.

All in all, though, both men were well armed for that time period and they were expert with their weapons. A betting man who knew their reputations might think the outcome of a shooting scrape between the antagonists would come down to a flip of a coin.

Quicker on the Trigger

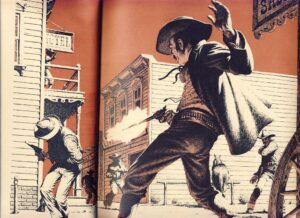

A short time later that night, a livid Courtright returned to the saloon, armed with his two Colt .45s “visibly holstered in his pockets” and bellowed for Short to come out. Soon Short did, and a couple of his friends–one of whom was Bat Masterson–accompanied him. The other friend, Jake Johnson, attempted to persuade Courtright to settle down. Instead, the adversarial gunmen wandered down the street, further debating Courtright’s demands. The hopping mad Courtright then accused Short of being armed, though Short fibbed and denied it. Without warning, Courtright snaked out a Colt when he and Short were within bad breath distance of each other.6 Not to be outdone, the swift Luke Short yanked his roscoe and center-shot Courtright once, and as Courtright flopped backwards into the dirt street, Luke pumped several more rounds into him until poor Jim shed his mortal coil.7

An Unsettled Controversy

Life in so many ways was simpler way back then, in particular when adjudicating fatal shooting frays. Luke Short was arrested but was soon let go because the authorities ruled that he was rightfully defending himself against a man who tried to kill him. Except for a half-hearted mob that clamored to hang Short—a common reaction in the Old West by the unwashed rabble–that was the end of it. No throngs of agitated do-gooders and whirling dervishes wailed about the sanctity of life and rampant violence. No years of half-baked criminal proceedings by bloviating prosecutors with dubious political agendas. And no dodgy wrongful death lawsuits were filed either. Edgy harmony, if there were such a thing then in old Fort Worth, was restored. In fact, upon hearing the shocking news about the demise of Long Hair Jim there may have been some very relieved local business people who secretly didn’t miss having Courtright around to plague them anymore.

Yet a question remained: Why didn’t Jim Courtright get off at least one shot? By reputation, the man was a fast gunslinger and seemed to be evenly matched with Luke Short. Several explanations surfaced: Short’s first shot blew off Courtright’s thumb holding his Colt. Or Short’s first shot hit Courtright’s revolver and disabled it. Or Courtright’s gun got snagged on his pocket watch chain. But after all this time we’ll never know for sure.

What Goes Around…

A mere two years later, again in Fort Worth, Luke Short participated in his last gunfight. His opponent was a fellow gambler named Charles Wright who had had a falling out with Short about a gambling debt. The dispute led to Short, revolver in hand, entering the Bank Saloon and searching for Wright. Likely aware of Short’s martial prowess, Wright ambushed him with a shotgun, badly wounding him in the leg and left hand. The shot to the hand supposedly blew off Short’s thumb, which may have been the genesis of the tale about what had led to the late Jim Courtright’s demise.

As it turned out, Luke Short’s earthly candle was beginning to gutter out. He passed away in September 1893 from kidney disease at age thirty-nine and was buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Fort Worth. His nemesis, Long Hair Jim, was also interred there and his headstone is inscribed, “Jim “Longhaired” Courtright 1845-1887 U.S. Army Scout, U.S. Marshal. Frontiersman, Pioneer, Representative of a Class of Men now passing from Texas, Who, Whatever their Faults, were the Type of that Brave, Courageous Manhood which commands Respect and Admiration”. Short’s gravestone has no epitaph, but a fitting one might be “Beware: small packages can be deadly.”

*****

Endnotes:

1.) Most of his early “kills” occurred while he was an Army scout fighting Native Americans. In two subsequent contretemps, Short badly wounded a gambler in Leadville, Colorado, and later killed another gambler, Charlie Storms, who had attacked him in Tombstone, Arizona.

2.) His actual birth name is a little cloudy. It was either Timothy Isaiah Courtright or James Timothy Isaiah Courtright. Contemporary written accounts refer to him as “Long Haired” Jim, “Longhair” Jim and “Big Jim”. Accounts disagree about his hair length, some claim that at times it reached his shoulders while others indicate it was not that long.

3.) The tavern still exists, though how much of it is original to the late 19th century is debatable. It was moved from its original location “to the Historic Stockyards in the 1970’s and has been one of Fort Worth’s premiere tourist attractions ever since.”

4.) Courtright served as the Fort Worth marshal from 1876 to 1879 and likely had the inside track on lots of opportunities, many of them unsavory.

5.) In the early 1880s, El Paso, Texas, formidable marshal Dallas Stoudenmire also carried a cutdown revolver, “a .44 Richards-Mason Army”, in addition to his twin .44 S & W No. 3 Americans.

6.) Gunfighters in those bygone days mostly preferred ambushing their adversaries, often by backshooting them from cover. Not very sporting by modern Hollywood sensibilities but a lot safer and surer for the shootist. “Wild Bill” Hickok, during his lawman career in Kansas cow towns, avoided certain parts of those places because he was aware that disgruntled Texas cowboys would try to bushwhack him.

7.) Modern readers might take a dim view of Jim Courtright, but in his day, he was popular with a lot of folks. His funeral procession was very large.

Sources:

Arnold, Jeff, “Luke Short the Gambler”, https://jeffarnoldswest.com/2021/06/luke-short-the-gambler/, Jeff Arnold’s West, June 11, 2021.

Harris, Karen, “Big Jim Courtright: 9 Things 1883 Didn’t Tell Us about the Old West Lawman”, https://www.oldwest.org/jim-courtright/, Old West, October 20, 2023.

Hutchcroft, Joel J, “Gunfighter Longhair Jim”, https://www.shootingtimes.com/editorial/gunfighter-longhair-jim/99411, Shooting Times, August 14, 2018.

Taffin, John, “Taffin Tests: The .45 Colt”, http://www.sixguns.com/tests/tt45lc.htm, John Taffin’s Sixguns.com., undated.

Rosa, Joseph G., The Taming of the West: Age of the Gunfighter, Smithmark Publishers Inc., New York, NY, c. 1993.

Venturino, Mike. “Big Bore Snubbies: Good Idea or Waste of Time?, https://americanhandgunner.com/handguns/big-bore-snubbies/, American Handgunner, undated,

White Elephant Saloon, https://whiteelephantsaloon.com/, undated.

*****

Lead Image From: https://www.youtube.com/live/RccXwilyLW8

There are few historians who can turn a phrase like that, Spencer. I sure enjoyed this one–beautifully written! Thanks for sharing your talent with us!

Thank you, Mike.

The more I research the Old West the more convinced I am of the corruption and explosive violence that happened frequently in that vast region. But when you mixed together rotgut booze, bad impulse control, psychopathy –and then tossed in little to no law enforcement–terrible repercussions were to be expected.

Puts current events in perspective, doesn’t it?

I was under the impression that it was a known fact that Luke Short’s first shot amputated Courtright’s thumb. Shows what I know.

Didn’t they do autopsies, or even look at the bodies of gunfight losers, back then? Didn’t anybody find a thumb lying in the street? Inquiring minds . . .

(By the way, my source for this story is a book called “Triggernometry,” written by a Texan named Eugene Cunningham and originally published in 1934. The chapter on the Courtright shooting is called “The Hammer Thumb,” which pretty much sums up his theory. It’s an interesting book, if you can overlook the casual racism.)

An interesting question, Old 1811. Even in the late 19th century larger and better organized cities conducted autopsies, or had a mortician examine a corpse for cause of death if murder was suspected. How long any of their records, if indeed anything was written, were kept is another matter. In many places administrative and court records eventually disappeared because of the lack of storage space, neglect, places becoming ghost towns, or were destroyed in fires or floods. It’s the bane of historians searching for answers.

After the subject gunfight, Short was arrested and had to appear before a grand jury, which did not indict him. How much time elapsed between the arrest and grand jury decision is not clear, but my guess is it didn’t take long.

If the cause of Courtright’s inability to get off a shot was ever determined by the police or court, I’ve not found any credible record of it.

Good write up Spencer.

A couple of Interesting fellows. See that suspension star on T.I. Courtright’s chest? I spent a lot of digging 30 some odd years ago when I was chasing badges and tracked it to the last family member that owned it.

Thought it was near the end of the chase and then found out it went into a gold melt pot at the local jewelry store.

History lost.

Wow. I’m legitimately impressed that you could track that star as far as you did. I’d have no idea how to even start. I’m glad there are people like you who have the knowledge and willingness to track down historic artifacts like that.

It’s too bad your (and the star’s) story doesn’t have a happier ending.

You hit upon the usual progression, Tony, of what happens to artifacts and written records: most don’t survive the passage of time. Then all that’s left is bad memories, hearsay, malarky and wishful thinking.

Sometimes historians get lucky with a newly found source (i.e., a diary, court record, last will and testament, object, photograph, etc.) that sheds new light on a subject.

Thank you for the excellent read, Mr. Spencer! It’s interesting to see how common the careless destruction of historical documentation occurs for the reasons you mentioned. I recall pulling up to the back of State Police headquarters one day and seeing our historian, Sgt Ron Taylor, literally dumpster diving. He was retrieving several boxes of precious history from decades past that were being thrown away by a new Lieutenant who was “decluttering” a storeroom at HQ. Taylor relocated all the old stuff into his police car and rescued old memos, pictures, directives from past chiefs, and even commission cards dating back to the 1930’s. Unbelievable that something like that happened, but it did more commonly than we would think, I suspect. Thanks for sharing this snapshot of a gunfight with us, Sir.

You’re welcome, Kevin.

Several decades ago I learned of a situation similar to Sgt. Taylor’s when I visited the city’s police museum in Fort Collins, Colorado. (Apparently it doesn’t exist anymore or perhaps it was absorbed by another museum.) The police officer/historian there told me about a prior police chief who had decided to “make space ” in his department’s evidence room. The result was loads of arms seized from bad guys over many years–knives, impact weapons, firearms of all types including three Thompson submachine guns–were tossed in the city dump.

When the police museum was established some retired cops learned of the police chief’s travesty and donated items they had confiscated from crooks and kept that formed the bulk of the museum’s exhibits.

Very interesting article Sir! I couldn’t help but wonder, if this gunfight was one of if not the earliest documented fight involving a “snub”. Im sure small guns had been carried and used prior to this incident but I wonder about full framed revolvers being modified like Short’s revolver . I am not very familiar with the single actions of that era and if they were manufactured with short barrel options.

Without doing some research I couldn’t state with any degree of accuracy when the first recorded “snub” gunfight occurred, Mark, though I’m sure there were more than a few prior to the Short/Courtright incident.

Snub revolvers, cut downs, and pocket revolvers were sometimes modified that way by, or for, their owners and carried well before the American Civil War. Gamblers, stagecoach lines such as Wells, Fargo (founded in 1852), gunfighters (like El Paso marshal Dallas Stoudenmire) and shopkeepers employed cut- down revolvers, often as hideout guns.

Years before revolvers were available, very short-barreled single-shot, cap-and-ball pistols such as those made by Henry Deringer and others were popular, especially with the “sporting crowd”.