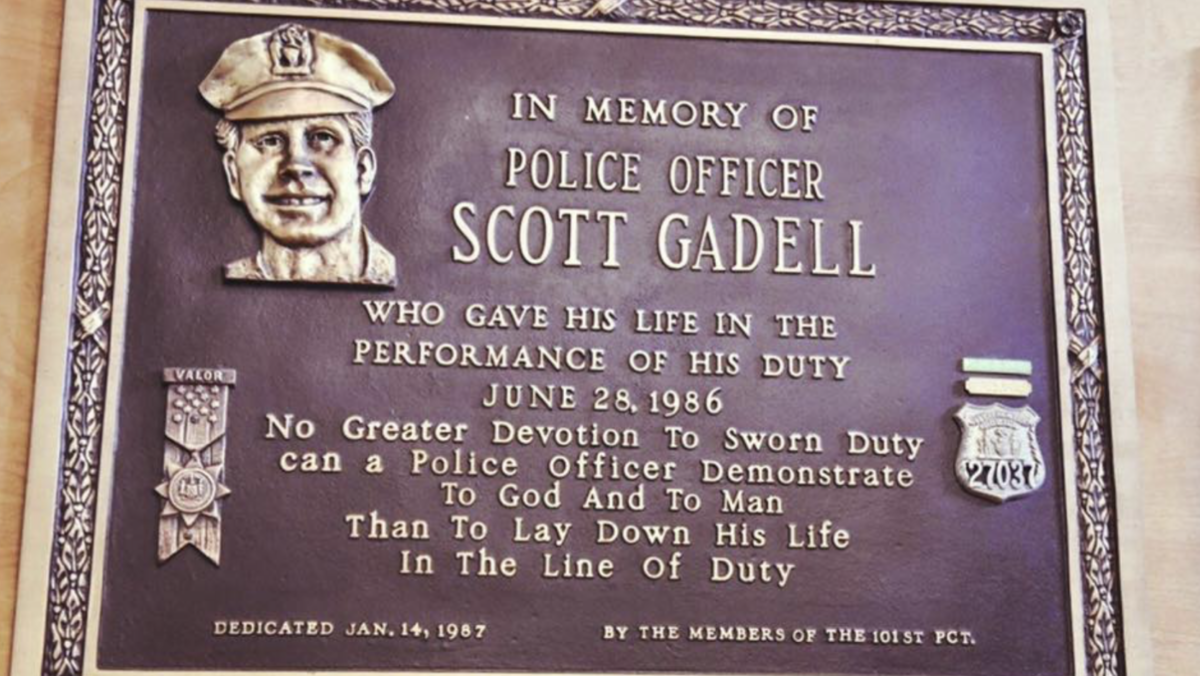

Having previously discussed the murder of New Jersey State Trooper Philip Lamonaco, and its influence on that agency’s decision to make the switch from revolvers to autopistols, we now turn our attention to the similar murder of New York City Police Department Officer Scott Gadell.

Like Trooper Lamonaco’s, Officer Gadell’s murder would have an immediate influence on his agency’s firearms policies, but it would take many years for the full effect to be witnessed. The story provides RevolverGuys and law enforcement officers some unique lessons and insights about the history of the revolver-to-auto conversion in American law enforcement, officer safety, and the nature of change in institutions like the New York City Police Department (NYPD).

GROUND RULES

We discussed this previously, in the Lamonaco analysis, but it bears repeating, once again.

The analysis of this gunfight may be critical of the officers’ actions at times, and highlight errors in tactics and decision making. My sole intent is to be constructive, and nothing I say should be construed as a personal attack on the involved officers or their legacies. I have the greatest respect for these men, their families, and their fellow officers, and aim to educate with these observations, not insult.

I believe the greatest insult to Officer Gadell would be to ignore the lessons that his sacrifice highlighted for us. If we fail to learn from his death, then we have failed him, so I won’t hesitate to be direct when necessary, and expect the audience to understand and appreciate the context in which these remarks are made.

“ROUTINE PATROL”

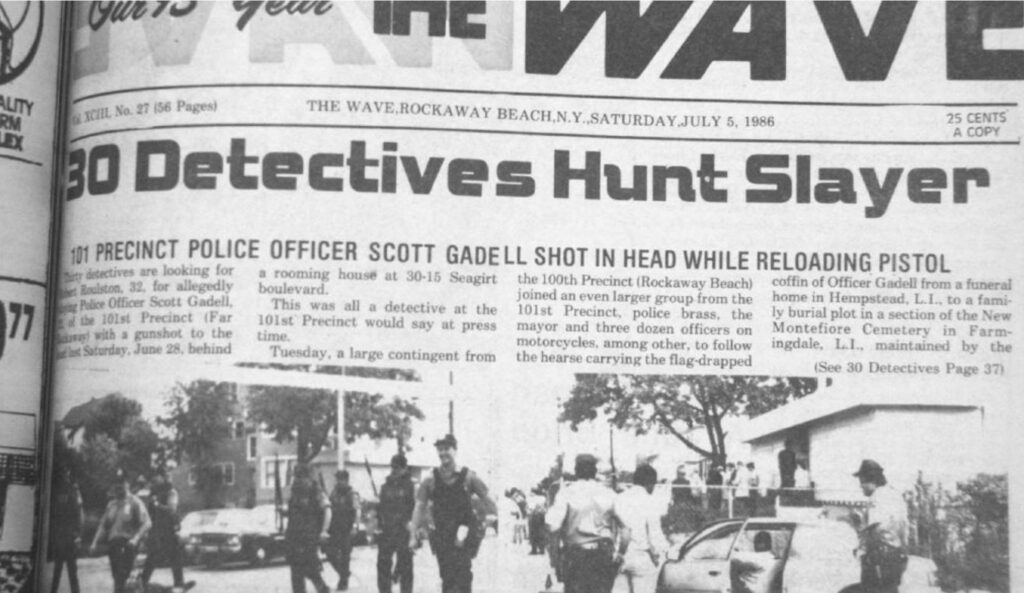

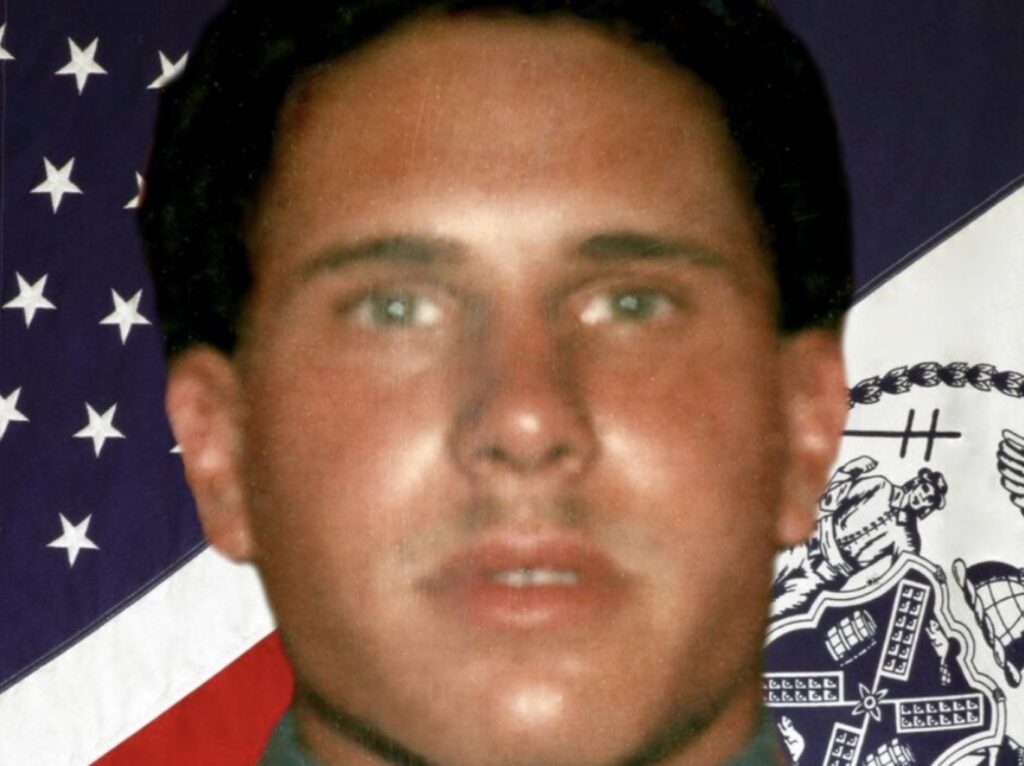

On the 28th of June, 1986, New York City Police Officer Scott Gadell was on patrol with his partner, Officer James Connolly, in the “Boy Sector” of the 101st Precinct.1 Both Gadell and Connolly were rookies—Gadell had been on the force for just under a year, having joined the NYPD on 8 July 1985, and Connolly only had a few more months of experience, as an April 1985 hire.2

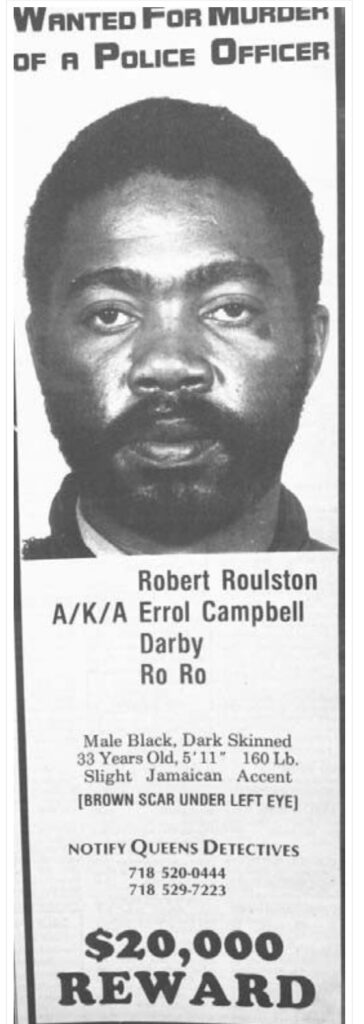

As the two officers drove through the Queens neighborhood of Far Rockaway, they were flagged down by a man named Gerald Gunter, who reported he had just been shot at by a man that would later be identified by police as Errol Campbell.3 Contemporary newspaper reports indicate that Campbell had been visiting with Gunter’s sister at the Deerfield Avenue home she shared with Gunter, and when her unhappy brother (and his male friend) confronted Campbell and told him to leave, an argument ensued. As Gunter and his friend followed Campbell outside, Campbell pulled a 9mm pistol and fired two shots at Gunter (both missed), then fled the scene. Gunter and his friend jumped into a car to track Campbell down, and in the process, they stumbled upon Officers Gadell and Connolly six blocks away, as they drove by in their RMP (Radio Motor Patrol car).4

THE SEARCH COMMENCES

Connolly and Gadell reported the job and provided a description of the suspect, then told Gunter and his friend to jump into the back of the RMP to go looking for him. With the pair’s help, the officers located the suspect and chased him for two blocks on foot, but lost him in a cluster of bungalows and rooming houses, and returned to their car to resume the search.

Just before 1445, the officers saw him again, running outside of a three-story rooming house at 30-15 Seagirt Boulevard, on the corner of Beach 31st Street. In their hurry to chase him, neither officer made a radio call to notify Dispatch and other officers about the unfolding pursuit.5

Connolly and Gadell exited the car to chase Campbell on foot, and Campbell fired a shot at the officers, which missed. At this point, the officers made a decision to split up, with Connolly going around the building on one side, and Gadell entering the alley on the other side of the building.6

As Gadell reached the alley, the suspect began firing at him from a recessed basement entry. Gadell moved towards the cover of a nearby stoop, and returned fire with his .38 caliber revolver. The two men were approximately ten to twenty feet from each other as they fired, according to court documents.

The suspect fired approximately seven rounds from his 9mm pistol at Gadell, and Gadell fired all six rounds in his revolver back at the suspect, hitting him in the arm. When his revolver ran dry, Gadell accessed the spare ammunition in his department-mandated dump pouch and began to reload his revolver, but his effort was cut short by an additional shot from the suspect, which struck him on the left side of the forehead, just above his ear.7

As the wounded suspect fled the scene, Officer Connolly ran around the building, found his wounded partner, and reported the gunfight on the police radio. He loaded Officer Gadell into the RMP and rushed him to Peninsula General Hospital, a mile away, but the wounded officer died on an operating table at 1817 that evening.8

PRESSURE BUILDS FOR CHANGE

The members of NYPD had been clamoring for more effective arms for patrol, like shotguns and semiauto pistols, since the early 1970s, but their requests had been routinely dismissed by police and civic leaders.9 The Gadell shooting breathed new life into those demands, however, and the bosses were finally forced to address them.

Yet, while the pace of life in New York City is accelerated, the NYPD–like many police organizations, large and small–doesn’t move quite as fast. There was still considerable resistance within the NYPD hierarchy to issuing autopistols to the troops, even after the Gadell shooting.10 Understandably, some of it was rooted in budgetary and logistical considerations, as the NYPD fielded some 27,000 officers at the time of Officer Gadell’s murder (as compared to the NJSP’s mere 2,000 troopers, at the time of Trooper Lamonaco’s death). The expense to re-equip the large body with new semiautomatic pistols, and the expense and difficulty of conducting the necessary training for a group that size, was daunting.

However, there were other factors at play in New York, as well. The bias against handguns ran deep in the city, with prohibitive laws like the 1911 Sullivan Act creating a vacuum of knowledge and experience about handguns that extended to the police department. Many of the decision-makers in the NYPD were afraid of semiautomatic pistols because they were raised in a culture that was inherently hostile towards them, and they were ignorant about the guns. 11

The mayor’s office was equally afraid of semiautomatic firearms, and joined the commissioner in his concern that officers equipped with such guns would shoot more rounds and recklessly endanger the extremely dense, urban population.

So, in the immediate aftermath of the Gadell shooting, the best that New York police officers could attain was a change in policy that allowed them to carry speedloaders, in lieu of dump pouches filled with loose rounds. The NYPD had finally caught up with agencies like the California Highway Patrol, which authorized the same equipment for its officers sixteen years prior, after the watershed Newhall gunfight.12

NOT TAKING “NO” FOR AN ANSWER

The pressure from the rank and file only continued to build, however, and when it was revealed that Police Commissioner Benjamin Ward and the Chief of Department were carrying the Glock pistols they had prohibited everyone else from using, they were forced to budge. In a face-saving effort, a limited test and evaluation program began in 1986-87, with 200 Glock pistols going to some specialized units (including members of the commissioner’s protective detail), and a number of Beretta 92D pistols going to the Emergency Services Unit. The first crack in the revolver dam had formed.13

The department dragged its feet however, and it took a concerted campaign from the Police Benevolent Association before a test and evaluation program for Patrol was finally launched by Commissioner Lee Brown, in 1991. The test was limited in scope though, and it took Brown’s reluctant replacement, Commissioner Raymond Kelly, several more years before he finally authorized NYPD Members of the Service (MOS) to carry semiautomatic pistols on patrol, in August 1993.14 But, even then, the pistols (S&W, Sig, and Glock) were modified to double action only, with a nominal twelve-pound trigger pull, intended to discourage negligent discharges from officers habituated to heavier revolver triggers. Additionally, they were issued with reduced-capacity, ten-round magazines, filled with full metal jacket ammunition.

The new guns, as originally issued, weren’t perfect, but at least the troops finally had them, and the situation would improve soon.15

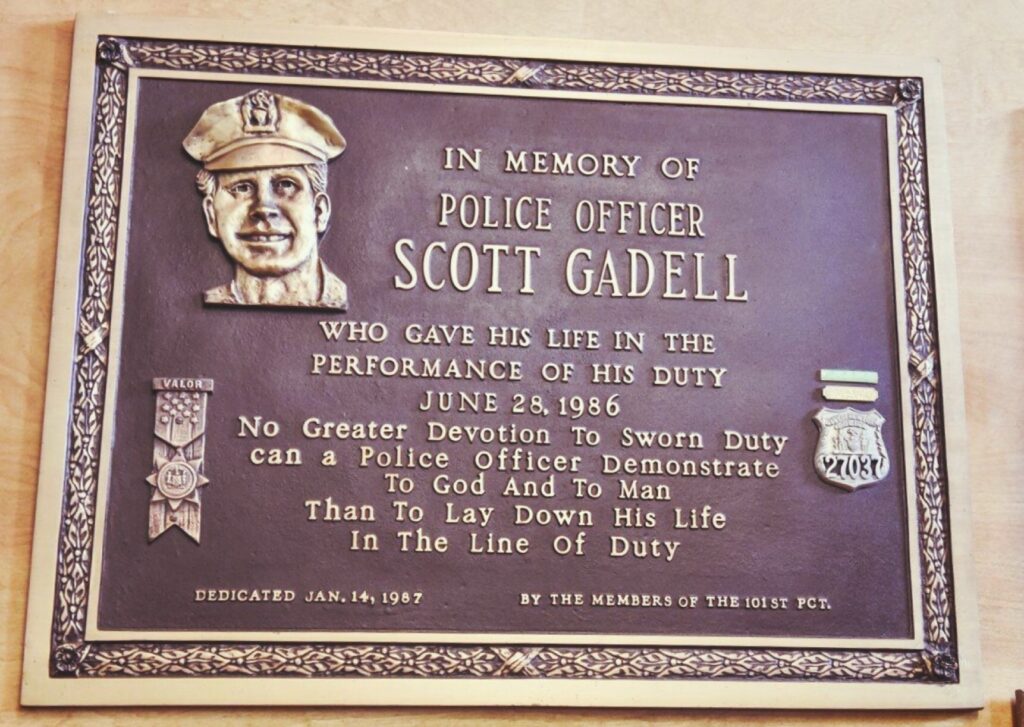

A legacy

It took seven years after Officer Gadell’s murder to get the autopistols the troops had been demanding. It had been a tough battle, but many officers believed Scott Gadell’s sacrifice marked a critical turning point in the effort. The speedloaders were the first change in the wake of his murder, but one could argue that the autos were Scott’s final legacy.16

The autos were a positive change for the members of the department, but a careful analysis of the Gadell shooting indicates that equipment issues were only part of the story, and perhaps not even the most important part.17 While the shooting would largely be remembered as a warning about the dangers of substandard equipment, there are other lessons that have been overlooked, which are worth our attention.

LESSONS

Some of the more important lessons of the Gadell shooting include the following:

-

- Warning signs. Campbell was known to be armed, and was obviously prone to violence, as someone who settled a verbal altercation with two gunshots. He was also demonstrably street savvy, having previously eluded the officers in their first chase of him. There were plenty of indicators that Campbell was not some ordinary suspect, but rather a determined adversary that demanded additional respect and caution from the officers. Yet, whether it was their inexperience as police officers, their youthful energy, the intoxicating spirit of the chase, or a mix of all the above, it appears that Officers Connolly and Gadell didn’t heed the warning signs. They didn’t request additional help, didn’t slow things down, and took on more risk than they could handle, with tragic consequences;

-

- Communication. It appears that Officers Connolly and Gadell did not make a radio call before initiating their second foot chase of Campbell. As a result, nobody knew they were engaged in a foot pursuit with an armed and dangerous subject. The first time anyone knew that Connolly and Gadell were in trouble and needed help was after Gadell had already been shot. The officers’ failure to communicate at the beginning of the pursuit also made it easier for the suspect to escape after he shot Gadell—had backup officers been on the way to the scene, they may have intercepted Campbell as he fled;

-

- Slow it down. Knowing when to go fast, and when to slow things down, is a critical officer safety skill. If Campbell’s previous activities hadn’t provided enough warning for the officers, the shot he fired at them as they got out of the RMP should have given them sufficient reason to slow things down. A radio call for help, establishing a containment perimeter, and conducting a slow and methodical search for the armed subject would have been appropriate in this circumstance. Instead, the officers seem to have rushed headlong into another chase, and Gadell probably entered the alleyway in a manner that was inappropriate for chasing an armed and dangerous suspect that he had already lost sight of–running blindly around the corner, in the open, rather than using available cover, and deliberately “pieing” the corner by degrees;

-

- Team tactics. There are advantages to splitting up a team, but disadvantages as well. In their attempt to locate the lost suspect, or trap him in a pincer movement, the two officers placed themselves in a situation where neither could provide immediate assistance and support to the other. Had Connolly and Gadell not split up, there would have been two guns firing on Campbell, instead of one, and that could have made the difference. It’s easy to “armchair quarterback” their decision now, in the aftermath, so it’s not fair to be too critical of the rushed decision, but it does provide an opportunity to highlight the dangers of splitting up a team, especially while hunting an armed and dangerous subject. Perhaps the advantage of mutual support outweighs the advantage of covering more territory in that situation? There are no easy or universal answers to most tactical situations, but “don’t leave your partner” seems like a pretty good baseline to start from, in most cases. If Connolly and Gadell were worried about cutting off additional avenues of escape, or expanding the search area, using the radio to summon additional help would have been a better option than splitting up;

-

- Use of cover. Officer Gadell apparently moved to the cover of a stoop when he came under fire from Campbell. This was probably an excellent choice in the moment, and it kept him in the fight for a longer period of time. However, the cover was soon inadequate to protect him from Campbell’s fire. Perhaps Gadell was too big to effectively hide behind it, perhaps he didn’t use it properly and allowed himself to remain exposed as he concentrated on reloading, or perhaps Campbell negated the cover by moving to another position.18 Whatever the case, it was not a permanent solution for Officer Gadell. This provides a useful lesson about not “getting attached” to cover, and realizing that every piece of cover has a timer attached to it. Officers should always be looking to improve their position, and this may require them to leave a position of cover to find a better one. In some cases, staying behind a piece of cover for an extended period may invite more risk than moving away from it, even if that travel is in the open, as it’s harder to hit a moving target than one which is immobilized;19

-

- Backup guns. Officer Gadell was certainly handicapped by his department issue dump pouches, because that reloading method is the slowest of all, and the most prone to error. He would have been much better off accessing a second weapon than trying to reload his primary weapon from the troublesome dump pouches while under fire—something that officer survival instructors of the era had been actively preaching since California Highway Patrol Officer James Pence was killed in similar circumstances, sixteen years prior, in the Newhall gunfight.

New York City police officers were authorized to carry backup weapons during this period and many savvy officers did, so it’s not clear why Officer Gadell was not armed with one of these lifesaving tools (or, if he was, why he didn’t use it). While many officers would later point to Gadell’s experience as an example of why revolvers were unsuitable duty weapons, due to their limited, six-round capacity, the truth is that Gadell could have quickly returned to the fight if he’d drawn another loaded revolver. A backup gun with five or six shots could have allowed Gadell to maintain continuity of fire and prevail–or at least stay in the fight long enough for Connolly to come to his aid, and tip the scales in their favor.

A semiautomatic with a higher capacity would certainly have been useful to Gadell as well, but would have offered no guarantees, either. Unfortunately, Officer Gadell’s situation was compromised by numerous tactical issues, and ammunition capacity was just one of them.

FORWARD!

We’re now more than three and a half decades downstream of the Gadell shooting, and it’s no longer necessary to seek examples to justify the use of semiauto pistols for law enforcement duties, as they’ve been the standard in policing for just about as long.

So, perhaps it’s time for us to view the Gadell shooting through a new lens, and focus on something other than the “capacity argument” that has come to characterize the tragic loss of Officer Gadell. There are so many other tactical lessons from the gunfight that are worthy of our attention, and it would be a different kind of tragedy if the same mistakes were repeated by a new generation of officers, who remained ignorant of them.

So, spread the word, focus on the software more than the hardware, and be safe out there.

*****

ENDNOTES:

1. Officer Connolly’s name was spelled differently in some newspaper accounts of the period, with an “e” in lieu of the “o”—Connelly. The police sources we reached out to indicated the “o” was correct, and it’s also the spelling used by the court in Campbell’s appellate decision, so that’s what we will use here. (Casetext.com, McFadden, Schwach);

2. It’s notable, but not unusual, that the pair of officers were rookies. It’s common in law enforcement agencies for rookie officers to be paired together on shifts that more senior officers prefer not to work. Unfortunately, this can lead to situations where inexperienced officers are left to deal with complex problems without the benefit of having more experienced officers to assist and guide them. That’s not desirable from a tactical standpoint, but it’s an inescapable part of a seniority-based system;

3. Campbell was a Jamaican drug dealer known to some as “Robert Roulston.” He was also known by his street names, “Darby” and “Ro Ro.” (Fried, McFadden);

4. The appellate court decision in People v. Campbell describes the initial confrontation between the parties differently than the newspapers did. According to the decision, Campbell had an argument with Gunter and his friend, then followed the pair as they left in a vehicle. When they stopped the vehicle, Campbell approached and fired two shots at them from a distance of three feet. Gunter and his friend attempted to flee, and Campbell initially chased them, but stopped when he saw the pair approach Officers Connolly and Gadell to report the shooting. While the sequence and details are different between the two sources, the core complaint is the same–Campbell attempted to murder Gunter and his friend, or at least committed an assault with a deadly weapon, by shooting his handgun twice at them. (Casetext.com)

5. It’s a little uncertain whether a radio call was made by the officers at this point, but the most detailed news report of the incident indicates this second foot pursuit wasn’t broadcast until after Officer Gadell was wounded. In response to a reporter’s inquiry, police investigators took the unusual step of explaining that, “it was usually up to an officer in the heat of a chase or a gunfight to decide at what point to summon backup help,” and that “no police procedures had been violated” by the officers. It’s unlikely police officials would have been compelled to make these statements unless they felt it was required to defuse accusations that the officers had committed some kind of policy or tactical violation, by not reporting the foot chase sooner. (McFadden)

There are many plausible explanations for why this second foot pursuit was not broadcast, at the start. It’s possible the officers didn’t want to lose the suspect a second time, so they rushed to exit the car and chase the suspect before they lost sight of him, again. It’s also possible that Campbell’s subsequent gunfire made them hurry to exit the car before making a radio call.

In the rush to jump out and chase Campbell, the officers may have accidentally left their portable radios behind in the car. Since the NYPD’s portable Motorola radios were large and heavy (officers jokingly called them “the brick,” since they were about the same size, shape, and weight), it was common for NYPD officers to to eschew the large, bulky, leather cases that were designed to carry them on the belt, and simply stuff the radios in a back pocket, when required. This made the officers much more comfortable, and saved valuable real estate on the belt, but also created an opportunity for the radios to get left behind on the seat of the car, when officers left in a hurry. (Personal interview with retired MOS)

We cannot discount the possibility that Connolly and Gadell chose to delay reporting the second foot pursuit, at the start, because they were worried about being embarrassed a second time. Everyone on the frequency probably knew they’d lost Campbell once before, so when they spotted him a second time, they might have chosen to wait until they had the “cat in the bag,” just in case. When subsequent events didn’t go as planned, it would have been too late to recover from the error.

All speculation aside, the important point is that it appears nobody else knew they were in pursuit of Campbell as the incident unfolded, so there was no backup on the way to help them;

6. In some reports of the incident, Campbell fired at the officers as they exited the vehicle, while other reports omit this detail. Similarly, in some reports (including the appellate court decision in People v. Campbell), Campbell is alleged to have fired a single shot at Officer Connolly during the incident, but the sequence is not made clear. Adding these fragments to the other things we know about the timeline, the author speculates that Campbell probably did fire at Connolly and Gadell as they exited the vehicle, and they made the decision to split up and chase him (possibly because they didn’t know where he had gone, in the confusion of getting shot at, or possibly as a conscious tactic to improve their odds of finding him, and cutting off his escape path).

The only other time Campbell could possibly have fired at Connolly was as he fled from the scene, but since the contemporary reporting indicates that Connolly didn’t know which direction Campbell had run off, after shooting Gadell, this seems unlikely. Apparently, the police were only able to reconstruct Campbell’s escape path with the assistance of witnesses and by following the blood trail from his wound.

So, with a little analysis and a healthy dose of speculation, the author is inclined to trust the reports that Campbell fired at Connolly and Gadell as they exited the RMP to give chase, and this was the only shot fired at Connolly during the confrontation. (Casetext.com, McFadden);

7. Not surprisingly, the accounting of shots fired by the suspect is a little sloppy, in the reporting of this incident. A New York Times article, published the following day, on the 29th of June, quoted police spokesman, Sgt. John Venetucci, as saying the suspect “fired seven times from a 9 mm automatic,” and Officer Gadell shot back, “firing six times.” However, the total number of shots fired by the suspect was updated to nine shots in a succeeding New York Times article on the 30th of June, “as indicated by shells found at the scene.” Succeeding reports from other sources also quote the total number of shots fired by the suspect as nine, and the tribute to Officer Gadell on the city’s website says nine shots were fired at him, specifically (not nine total, but nine fired at Gadell).

The author resolves the discrepancies in this manner. If police recovered nine (9) fired cases from Campbell’s gun (and they didn’t miss any, at the scene), Campbell likely fired a single shot at both Connolly and Gadell as they exited their RMP, then eight more at Gadell while they fought in the alley, including the fatal one that struck Gadell in the head. (City of New York, Hevesi, McFadden);

8. The suspect was captured by police seven weeks later, at an apartment building in Brooklyn. His attempt to flee via the fire escape was cut short by several detectives, who arrested him after a short struggle. The suspect had a loaded .45-caliber pistol under his shirt, but did not draw it during the confrontation. (Fried);

9. A number of high-profile attacks on NYPD officers by the Black Liberation Army (BLA) helped to prompt the demand for better weapons, during this period.

On 19 May 71, Officers Thomas Curry and Nicholas Binetti were grievously wounded in a drive-by ambush on their RMP, conducted by suspects armed with an automatic, .45 caliber M3 submachinegun. Officer Binetti was struck eight times, and Officer Curry was hit multiple times in the face, neck and chest. Both survived their grievous wounds.

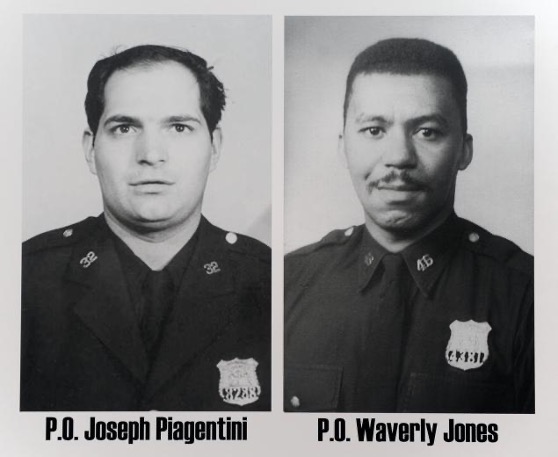

Officers Joseph Piagentini and Waverly Jones weren’t as lucky. They were killed in a planned ambush on 21 May 71, as they responded to a fake disturbance call in the Colonial Park Houses on W. 159th Street. As they were returning to their RMP, Officer Jones was shot in the back of the head with a .45 ACP 1911 pistol from near-contact distance, and another three times in the neck, back and thigh, as he fell. Officer Piagentini was shot to the ground with .38 Special gunfire and a round from the .45 auto that killed his partner. Officer Piagentini pleaded for his life while he was on the ground, but was disarmed by the group and killed with his own service revolver. Officer Piagentini was shot a total of 13 times (12 times with .38 Special, once with a .45 ACP) and suffered 22 entry and exit wounds on his body.

Two of the killers were involved in the murder of San Francisco Police Sergeant John Victor Young, a few months later, on 29 Aug 71. Officer Jones’ stolen weapon was recovered at yet another scene in San Francisco, when BLA members (including Officer Jones’ killer) unsuccessfully tried to ambush and murder another San Francisco police officer with the M3 submachinegun that had previously been used in the Binetti-Curry attack.

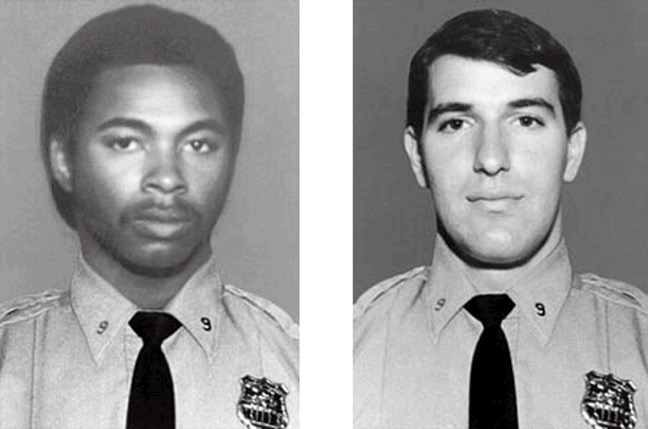

Officers Gregory Foster and Rocco Laurie were also killed in an ambush on 27 Jan 72, while walking their 9th Precinct beat on Avenue B and East 11th Street. A group of three BLA members passed the officers on the sidewalk, then turned and fired upon them from behind with automatic pistols (one .38 ACP, and two 9mms). Officer Foster was shot eight times, and Officer Laurie, six. As the wounded officers lay on the ground, members of the group fired three more shots into Officer Foster’s eyes, and two additional shots into Officer Laurie’s groin, then took their service weapons from them.

One of the suspects in the Foster and Laurie murders was also involved in the earlier murders of Officers Piagentini and Jones, and was later arrested and convicted for those murders. A second suspect was arrested at the scene of a gunfight with St. Louis, Missouri, police on 14 Feb 72, with Officer Laurie’s gun in his possession.

On 25 Jan 73, Officers Carlo and Vincent Imperato were ambushed by a BLA member armed with a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), who fired at least 23 rounds at them on full auto, wounding both.

These, and other “ordinary” assaults on NYPD officers, prompted Edward J. Kiernan, the head of the police union, to call on civic and police leaders to arm the city’s officers with shotguns. When the brass refused, Kiernan encouraged the men to carry their privately-owned shotguns on patrol anyhow, in violation of policy, and many did just that. Some veteran officers from the era report that they carried unauthorized Magnum revolvers and semiautomatic pistols, as well, in response to the spike in anti-police violence. (Burroughs, Conlon, Officer Down Memorial Page, Tannenbaum & Rosenburg, Thee Rant Forum, personal interviews with retired MOS);

10. Captain John C. Cerar, the commanding officer of the NYPD’s Firearms and Tactics Section in 1986, argued that NYPD officers were rarely involved in gunfights where a reload was required—citing only 8 such instances in 1985—and suggested that special teams, like the Emergency Services Unit (ESU), could quickly respond to incidents with more effective weapons, if required. “In a typical situation, a 9-millimeter semiautomatic is not necessary in New York City,” said Cerar.

Cerar also argued that the revolver was inherently more reliable than a semiautomatic pistol, and its .38 Special ammunition was less likely to over-penetrate and injure innocents in dense, urban environments, than 9mm ammunition.

Commissioner Lee P. Brown (1990-1992) would echo the same themes, years later, in a May 1992 report about the selection of firearms for police officers. Commissioner Brown wrote, “ . . . evidence to date shows that [the revolver] is the safest and most effective weapon for the police officers and the citizens of this city,” and that:

“Preliminary indications are that the semi-automatic pistols may increase the danger to both police officers and bystanders. This opinion is based upon a finding that the Glock 9mm semiautomatic has jammed, leaving officers with no defense under fire. Equally disturbing is the greater risk of accidental discharges and the increase in number of rounds fired that would endanger innocent bystanders and police officers.”

It took Commissioner Brown’s replacement to finally approve the use of semiautomatic pistols for general patrol use. (Brown, Hill, and Unknown Author, The New York Times, 27 Sep 86);

11. To illustrate the effect of this ignorance on policy, department leaders instituted a specific ban on Glock pistols in early 1986, prohibiting Members of Service (MOS) and non-sworn, pistol license holders from owning and using the guns within city limits, based on the ludicrous, and easily disproven, fear that the gun’s plastic frame made the gun invisible to metal detectors. (Barrett, p.62);

12. Regarding the tardy speedloader authorization, one former NYPD member wryly quipped:

“If it weren’t so pathetic it would be funny—the NYPD incessantly testing things that have already been proven effective by the rest of the law enforcement world. And, naturally, of the two brands available, it selected the inferior version.”

Some veteran MOS of the period have recalled carrying speedloaders, in contradiction to policy, before they were formally authorized by the department, but the practice was isolated (one veteran MOS estimated that less than 10% of the officers openly carried them on their duty belts, out of policy). It seems that the use of a strip loader (like the popular Bianchi Speed Strip) would have offered an even more discreet way of violating the department policy, while still offering a significant improvement over loading loose rounds from the pouch, but it doesn’t appear that this practice was common in the NYPD, either.

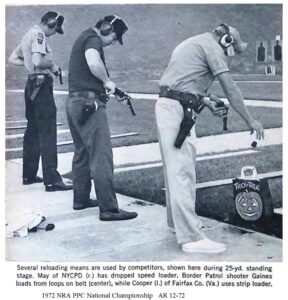

Of special note, the NYPD’s competition shooting team was using speedloaders in matches as early as 1972, fourteen years before Officer Gadell was murdered. In photos from the 11th Annual National Police Combat Pistol Championships, held in October of 1972, in Jackson, Mississippi, NYPD shooter Frank May is shown using a speedloader (which appears to be a Hunt Multi Loader) alongside officers from other agencies that are loading from loops and with Speed Strips. Lt. Frank McGee, the Commander of the Firearms Section of the NYPD, was present at the games, and actually had the honor of presenting the winning medal to the National Champion.

Thus, the NYPD, and the people most responsible for its firearms training, were certainly not ignorant of speedloaders prior to the Gadell shooting. Indeed, they believed the loaders offered such a compelling advantage, that they allowed their shooting team to use them in violation of the “spirit of the games,” which encouraged shooters to compete with reasonable analogues of their duty gear. It’s a damned shame that they didn’t give the troops in the field access to the same advantage in the arena where it counted most—the street.

When the NYPD finally did make the decision to approve the speedloaders, it happened fast. Police sources tell RevolverGuy that the speedloader authorization was the fastest equipment/policy change ever made by the NYPD. Much, if not all, of the bureaucratic red tape that would normally delay such a change was bypassed, as the department hurried to fix the glaring equipment deficiency. (Harris, Thee Rant Forum–22 May 2011, personal interview with retired MOS and police sources);

13. The Glock pistols reportedly went to selected individuals in Narcotics, Homicide, TARU, the Major Case Squad, and the commissioner’s detail, but not to any officers assigned to Patrol. (Barrett, p.64, and GlockTalk Forum, 24 Nov 17).

Gunwriter Ed Sanow dates the timeline slightly differently, with NYPD ESU purchasing its first Beretta 92 pistols in May 1985, the Firearms & Tactics Section starting a Glock test in November 1986, and the first phase of Glock 19 pilot program beginning (with OCCB detectives) in October 1988. Sanow states the second phase began in January 1991, when Commissioner Lee Brown expanded the test to some patrol officers, followed by a Phase Three expansion to a greater number of patrol officers in January 1993. Per Sanow, Commissioner Kelly decided to transition the entire department to 9mm pistols in August 1993. (Sanow)

A RevolverGuy reader, who was assigned to OCCB, and received his Glock 19 as part of the first test phase, provided a copy of the NYPD’s 1990 Firearms Assault Discharge Report, which states the Firearms and Tactics Section commenced Phase One training on April 3, 1989, and in calendar year 1990, 558 MOS had attended the training–353 from OCCB, 125 from the Detective Bureau, and 61 from the Intelligence Division/Police Commissioner’s office. The remaining 19 were assigned to the Firearms & Tactics Section.

14. The details of these programs and authorizations are a study in big city politics and bureaucracy.

Commissioner Kelly reportedly approved semiautomatic pistols for the NYPD Academy class of August 1993, and approved a transition program for all patrol officers, under protest. One version of the story says that Kelly only approved the pistols under pressure from Mayor David Dinkins. Dinkins was losing his reelection campaign to Rudy Giuliani, a candidate who was known for being “tough on crime,” and thought the announcement of a new autopistol program would help boost his crimefighting resume. It’s said that Kelly reluctantly started the transition program, as directed, but added a poison pill, by mandating ten-round magazines.

Another version of the story says that Dinkins was reluctant to approve the semiauto pistols because he was concerned about the negative reaction it would generate in certain segments of the voting public. As a way to duck the issue, and simultaneously appease the pro-law enforcement voters who wanted the change to happen, Dinkins reportedly blamed budgetary restrictions for killing the deal. That worked until his political adversary, Governor Cuomo, called his bluff by offering to pay for the new guns with state funds.

We can’t say for sure how the sausage was made, but however it came about, Kelly signed the August 1993 authorization, but allowed the program to stall out when Mayor Dinkins lost his race, shortly thereafter. The abandoned program had to be revived by Kelly’s successor, Commissioner William Bratton, who had been serving as the commissioner of the New York City Transit Police Department for the previous four years. Bratton had already approved autos for the members of the Transit Police (the separate Housing Authority Police Department officers were also carrying them, already), so it was no surprise when he resumed the NYPD transition program in March of 1994.

Of note, Kelly was still defending his choice of ten-round magazines in the Op-Ed page of The New York Times, years later, in the wake of the Amadou Diallo shooting. (GlockTalk Forum—24 Nov 17, Kelly, Personal interview with retired MOS, Thee Rant Forum—13 Jul 13);

15. The ten-round, limited capacity magazines were quickly replaced with normal capacity, fifteen-round magazines, by the new police commissioner, William Bratton, before any MOS were required to actually carry them on duty. Bratton was allegedly influenced to make the change after NYPD Officer Arlene Beckles ran her 5-shot snub dry in an off-duty shooting involving three suspects. Beckles killed one of them, but was pistol-whipped by one of the others after her revolver ran dry.

Unfortunately, the FMJ ammunition lasted much longer in the NYPD. Even though jacketed hollowpoint ammunition (JHP) had been the industry standard for autopistols for more than a decade (and for revolvers, for almost two decades), the non-gun-savvy civic and agency leaders in New York were hesitant to issue such “controversial” and “unreliable” ammunition to the troops. The decision to replace NYPD’s full metal jacket (FMJ) ammunition with JHP ammo was not made until July 1998, and the transition to JHP had just begun when a high-profile, February 1999 shooting occurred, in which FMJ rounds fired by officers penetrated through a subject and ricocheted back towards the officers. This led some officers in the group to mistakenly believe the unarmed subject was shooting at them, which regrettably prompted more unnecessary police gunfire, in the confusion.

The NYPD accelerated the issue of JHP ammo after the incident, and in March 1999 they fielded the excellent, 9mm Speer Gold Dot 124+P JHP to officers armed with autos, and the .38 Special Federal Nyclad 158+P JHP to officers armed with revolvers. The success of the 9mm Gold Dot prompted the department to request a similar load for revolver-armed MOS, and Speer responded with the excellent, .38 Special Gold Dot 135+P JHP, around 2003. Both of these Gold Dot loads remain in NYPD service, today.

Fortunately, the NYPD’s heavy triggers will eventually sunset. In late 2021, the NYPD began to issue Glock pistols with standard-weight (nominal, 5.5-pound) triggers to new recruits, over concerns that the heavy triggers mandated by the department were negatively affecting officers’ accuracy in line of duty shootings. These concerns had been voiced for a long time, and seemed to reach a pitch after a high-profile shooting in 2012, in which a pair of officers injured nine bystanders with gunfire, while shooting at a single suspect. The wheels still turn slow inside the NYPD however, and it took an additional nine years before the easier-to-shoot guns were issued to new recruits.

Under the current policy, veteran officers are still not able to replace their older duty guns (with heavier, 12-pound triggers) with new, 5.5-pound trigger Glocks. It’s unlikely the department will replace or modify the older guns on the city’s dime, but we can hope that veteran NYPD MOS will eventually be able to purchase their own Glocks with 5.5-pound triggers for duty use. Barring that, the heavy-trigger guns will simply fade away with time, as the officers equipped with them retire. (GlockTalk Forum–24 Nov 17 and 13 Aug 16, and; Personal interview with retired MOS, and; Wilson, Warren, and; Sanow);

16. By 2016, this had become the department’s official position. At a 30th anniversary ceremony honoring Officer Gadell, Chief of Department James O’Neill said, “Scott’s murder prompted the NYPD to use speed loaders [for] revolvers and eventually move into semi-automatic pistols.” (Marcius)

17. In a 31 May 92 New York Times article about arming NYPD officers with semiautomatic pistols, Officer Robert James Evers of the 71st Precinct, in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, told reporters, “Every cop knows about Scott. He’s an example of a cop who did everything he was supposed to, but wound up dying because of second rate equipment.”

Like their military brethren, law enforcement officers frequently distill complex events into simplified narratives that are more digestible for debriefing and training purposes. Unfortunately, some of the educational value associated with these events is lost in the translation, particularly when details are lost as the story gets passed from generation to generation, and survives in institutional memory as little more than an anecdote.

While Officer Evers’ understanding of the Gadell shooting is probably the baseline now in the NYPD, the truth is more complex. Equipment deficiencies are certainly part of the story, but today’s officers would cheat themselves of valuable officer safety lessons if they blamed Officer Gadell’s death solely on his gear. Officer Gadell’s equipment issues were simply the last link in a chain of problems that began with critical tactical mistakes. (Unknown Author, “Memory of a Fallen Officer,” The New York Times, 31 May 1992, reproduced at Thee Rant Forum–22 May 2011);

18. Officer Gadell’s family later indirectly suggested that an NYPD “training scar” regarding the use of cover could have contributed to his death. “They used to teach you to crouch and turn [while conducting a reload],” claimed Gadell’s brother, in a 2016 interview, inferring that this trained response put Gadell in a compromised position. (Mongelli)

There are numerous reports that Campbell sneaked up on Gadell, unnoticed, and shot him at a close distance while Gadell was turned and focused on reloading his gun (indeed, this seems to be the prevailing understanding, particularly among retired MOS who served during the period), but this author has been unable to verify the claim with more than just anecdotal evidence.

It’s certainly possible that Gadell was rushed and killed without seeing Campbell approach because he was turned away, but it’s also possible that he was simply shot in the side of the head as Campbell fired from the basement recess, which was only “ten to twenty feet” away from Gadell (per New York Supreme Court documents).

It’s tempting to go with the widely-accepted “ambush” version as the baseline, but this author is hesitant to do so until more authoritative evidence confirms it, based on his experience investigating these kinds of events. If any RevolverGuy readers can provide better information, I’d be eager to discuss it with them.

It’s important to note that even if Gadell hadn’t reflexively “crouched and turned,” as a result of his training, his cover may have forced him into that position, anyhow. The downward slope of the stoop would have presented the most cover up against the side of the building, and diminishing cover as the distance from the side of the building increased. It’s reasonable to assume that Gadell would have tried to maximize this coverage by trying to hug the side of the building as he reloaded. If he put his back to the building to accomplish this, he would have exposed his left side profile to the suspect. Reflexively hunching over his gun, to focus on the work and make himself “small,” would have caused Gadell’s head and shoulders to move forward and become more exposed, as he leaned away from the building and the high point of the stoop that sloped away from him.

Gadell was in a position where he had to choose between maximizing his cover and maintaining his mobility. Sitting on his bottom or laying down would have lowered his profile, and allowed him to do a better job of staying behind the low stoop, but it also would have left him more vulnerable to a flanking attempt by Campbell, by robbing him of his mobility, and it would have slowed his pursuit of Campbell, if Campbell had chosen to disengage and run away. Again, with the limited information we have, it’s not possible to know what choices Gadell actually made, but it’s not unreasonable to think that Gadell chose to favor mobility over cover, and got hit in the head because of his greater exposure, not because he failed to see Campbell’s assault on his position until it was too late.

Of note, after the Gadell shooting, NYPD trainers admonished their students to “Look as You Load,” as a reminder to maintain situational awareness while the gun was out of action. Whether or not Gadell actually made the tragic mistake of failing to watch his opponent as he reloaded, this was a positive change in NYPD training. The new training practice built better habits, and potentially saved other officers from Gadell’s fate. Whether it was born of an actual error or a misunderstanding, it was a good result from a bad situation. (Personal interview with retired MOS, Police Benevolent Association of the City of New York press release, and GlockTalk—24 Nov 17);

19. Police trainer, and officer safety expert, Brian McKenna notes that these important lessons about the use of cover were a direct outgrowth of the “officer survival” movement of the 1970s and 1980s, which was inspired by events like the Gadell murder. “Cops are much better trained in tactics today, than they were in 1986,” notes Brian, “and would be more likely to handle that kind of situation differently, as a result of the improved training.”

Importantly, the working environment has also shifted for today’s officers, many of whom would now be prohibited by department policy from initiating or continuing a foot chase to begin with, particularly if they had lost sight of the suspect. This is, in part, a recognition of the fact that foot chases are high risk activities, which offer a suspect many opportunities to ambush a pursuing officer, as Campbell did to Officer Gadell.

Of course, the present “soft on crime” culture, and law enforcement’s response to it, has also contributed to a significant decrease in foot pursuits. But, if history is any guide, the public will eventually change their minds about policing, and start to demand more aggressive law enforcement again. When they do, a whole generation of cops will have to learn skills they either were never taught, or allowed to atrophy, like how to safely conduct a foot pursuit. The law enforcement profession is not yet finished with learning from Officer Gadell’s sacrifice;

20. Since we’ve spent so much effort chronicling the adoption of autopistols by the NYPD in the wake of Officer Scott Gadell’s death, it makes sense to tell the related story about the fate of the revolvers they replaced, too.

In agencies like the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department (1988) and the California Highway Patrol (1990), when revolvers were finally replaced with autos, all personnel were required to transition to the new equipment—there were no grandfathered exceptions allowed. However, the NYPD, like the Los Angeles Police Department, allowed its officers to retain their revolvers as service weapons if they didn’t want to transition to the new guns, and a mixed fleet of guns patrolled the streets.

By the early 2000s, there were just a few thousand MOS still carrying revolvers as primary service weapons on the NYPD (2,018 as of Fall, 2004), down from more than 30,000 in 1993, when the auto transition began for Patrol officers. The holdouts continued to dwindle in the coming years (reaching 214 MOS, in 2015), as revolver-equipped officers either retired, or agreed to transition to the 9mm.

By late 2017, it had become a logistical and administrative burden to support the few remaining service revolvers, so the NYPD decided to retire them. A department memo directed all remaining revolver-equipped MOS (whose numbers may have dwindled to as low as 29, according to one source) to transition to 9mm autos, starting on 1 Jan 18. Revolvers would no longer be authorized as service weapons starting 31 Aug 18, but MOS who had originally been issued revolvers could opt to carry them off duty, if they did not already have an off duty weapon on file.

Under the new policy, some department-approved revolvers (such as the .38 Special S&W Model 640 and 640-2) would continue to be authorized as backup or off duty weapons, but the service revolver era had finally come to an end on the NYPD. (Messing, and; Wilson, Michael).

REFERENCES:

Books:

Barrett, Paul M., Glock: The Rise of America’s Gun, Crown Publishers, 2012.

Burrough, Bryan, Days of Rage, Penguin Books, 2015.

Tannenbaum, Robert and Rosenberg, Philip, Badge of the Assassin, E.P. Dutton, 1979.

Magazine Articles:

Harris, C.E., “NRA Police Combat Pistol Championships,” The American Rifleman, December 1972;

Pagano, Colonel Clinton L., “The 9mm Auto as Police Sidearm,” The Police Marksman, Jan/Feb 1984.

Sanow, Ed., “Why the NYPD Changed to Hollowpoints,” Handguns Annual, 2002.

Wilson, Warren, “NYPD Should Issue Glocks With a Standard 5-Pound Trigger to All Officers, Not Just New Recruits,” www.police1.com, 1 Nov 2021, located at: https://www.police1.com/patrol-issues/articles/nypd-should-issue-glocks-with-a-standard-5-pound-trigger-to-all-officers-not-just-new-recruits-5iC32Rg8arabmUgV/

Newspaper Articles:

Fried, Joseph, “Man Seized in Slaying of Officer,” The New York Times, New York, NY, 19 August 1986, located at: https://www.nytimes.com/1986/08/19/nyregion/man-seized-in-slaying-of-officer.html

Hevesi, Dennis, “A Rookie Police Officer is Killed in a Shoot-Out in a Queens Alley,” The New York Times, 29 June 1986, located at: https://www.nytimes.com/1986/06/29/nyregion/a-rookie-police-officer-is-killed-in-a-shoot-out-in-a-queens-alley.html

Hill, Amy Hearth, “Police Turning to 9mm Guns to Fight Crime,” The New York Times, 12 Mar 1989, located at: https://www.nytimes.com/1989/03/12/nyregion/police-turning-to-9-mm-guns-to-fight-crime.html ;

Kelly, Raymond W., “The Police Department’s 9-Millimeter Revolution,” The New York Times, 15 Feb 1999, located at: https://crab.rutgers.edu/users/goertzel/9-mill~htm

Marcius, Chelsia Rose, “Queens Ceremony Honors Memory of NYPD’s Scott Gadell, Slain While Reloading Low-Capacity Weapon in 1986,” New York Daily News, 29 Jun 2016, located at: https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/queens/nypd-ceremony-honors-slain-reloading-low-capacity-gun-1986-article-1.2692979

McFadden, Robert D., “Wide Hunt for Killer of Officer,” The New York Times, New York, NY, 30 June 1986, located at: https://www.nytimes.com/1986/06/30/nyregion/wide-hunt-for-killer-of-officer.html

Messing, Phillip, “Dwindling Number of Cops Still Allowed to Carry Six-Shooters,” The New York Post, 8 September 2015, located at: https://nypost.com/2015/09/08/dwindling-group-of-cops-still-allowed-to-carry-six-shooters/

Mongelli, Lorena, “NYPD Remembers Slain Rookie Cop 30 Years Later,” New York Post, 29 June 2016, located at: https://nypost.com/2016/06/29/nypd-remembers-slain-rookie-cop-30-years-later/

Schwach, Howard, “20 Years Later, Rockaway Remembers PO Scott Gadell,” The Wave, Rockaway Beach, NY, 6 July 2006, citing articles from the 5 July 1986, 26 July 1986, and 23 August 1986 editions of the paper, located at: https://www.rockawave.com/articles/20-years-laterrockaway-remembers-po-scott-gadell/

Wilson, Michael, “In New York, Old-School Officers Swear by the Vanishing .38,” The New York Times, 16 December 2004, located at: https://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/16/nyregion/in-new-york-oldschool-officers-swear-by-the-vanishing-38.html

Unknown Author, “Often Outgunned, Police Are Bolstering Firepower,” The New York Times, New York, NY, 27 Sep 1986, located at: https://www.nytimes.com/1986/09/27/nyregion/often-outgunned-police-are-bolstering-firepower.html

Websites and Online Resources:

Brown, Commissioner Lee P., “The Choice of Handguns for Police Officers: Revolvers or Semi-Automatics,” archived by United States Department of Justice, located at: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/145560NCJRS.pdf

Casetext.com, People v. Campbell, 208 A.D.2d 641, 617 N.Y.S.2d 195 (N.Y. App. Div. 1994), Located at: https://casetext.com/case/people-v-campbell-63

City of New York (Website), “Fallen Finest,” located at: https://www.nyc.gov/assets/nypd/downloads/pdf/fallen-heroes/0628_QS_Gadell.pdf

Conlon, Edward, “The War at Home: Remembering Foster and Laurie,” 19 July 2018, located at: https://www.nyc.gov/site/nypd/news/f0719/the-war-home-remembering-foster-laurie#/0

GlockTalk Forum, “Service Revolvers No Longer Authorized,” writer posting as “seanmac45”, 24 Nov 2017, located at: https://www.glocktalk.com/threads/service-revolvers-no-longer-authorized.1682812/page-6

GlockTalk Forum, “News from the NYPD Range,” writer posting as “seanmac45”, 13 Aug 2016, located at: https://www.glocktalk.com/threads/news-from-the-nypd-range.1630602/page-5

Officer Down Memorial Page, entries for Scott A. Gadell, Joseph A. Piagentini, Waverly M. Jones, Gregory P. Foster, Rocco W. Laurie, and John V. Young, located at: https://www.odmp.org/

Thee Rant Forum, “The Great Debate, DaNine,” multiple writers, posting 13 Jul 2013, located at: https://www.tapatalk.com/groups/theerant/the-great-debate-danine-t60356.html

Thee Rant Forum, “06/28/1986 Police Officer Scott A. Gadell,” multiple writers, posting 19 Jun 2008 to 4 Feb 2017, located at: https://www.tapatalk.com/groups/theerant/06-28-1986-police-officer-scott-a-gadell-t6125.html

Thee Rant Forum, “Police Officer Scott A. Gadell – 06/28/1986,” multiple writers, posting 28 Jun 21, located at: https://www.tapatalk.com/groups/theerant/police-officer-scott-a-gadell-06-28-1986-t111813.html

Thee Rant Forum, “5 Gunfights That Changed Law Enforcement,” writer posting as “RetirementIsParole,” 22 May 2011, located at: https://www.tapatalk.com/groups/theerant/5-gunfights-that-changed-law-enforcement-t41467.html

Other Resources:

Police Benevolent Association of the City of New York, Inc., press release, dated 9 June 2021, located at: https://www.nycpba.org/press-releases/2021/as-albany-weighs-parole-changes-another-cop-killer-walks-free

Featured image from: https://www.rockawave.com/articles/remembering-officer-scott-gadell/

While I enjoy the these articles, the endnotes are amazing. Somehow they are even more interesting than the actual topic…. Every single article. Not sure how you doing but keep them coming.

Thank you! These take a lot of work, but I think it’s worth it, to capture the important lessons. Be safe!

Another excellent analysis of an encounter gone wrong. Once again, we have a version of Newhall repeating itself for the umpteenth time.

Putting rookies together on the street out of an academy is a horrible idea, and NYPD should have (and probably did) known better. My first 3 months post academy in 1972 (A.D., not B.C.) was with a 20 year patrol veteran. His first advice was to forget everything I’d been taught in patrol school because the street was a whole different kind of academy. There was a lot of good things taught in the classroom, but there was an incredible amount of leftover rubbish from the stone age.

There was obviously a mindset within the NYPD of chasing down the bad guy(s) first and thinking about what you’re doing second. Also, New York, among too many other jurisdictions, suffers from hoplophobia. The result is a firearm illiterate pool from which to recruit police, and led by an equally firearm illiterate hierarchy to direct policy. The lack of a gun literate culture results in officers having that one revolver that they carried for 30 years, and have no earthly idea how any other firearm works. After all, the revolver worked for grandpa when he was on the job.

The policies of police brass are too often based upon political appearances rather than what is best for those on the street. Everyone needs to look neat and clean like Adam-12 instead of facing the reality of the job. Most police brass have not seen the inside of a patrol car in so long they can’t tell you what piece of equipment does what, so one can’t expect to have quality of policy.

Policy changes, when they do happen, are usually reactive in nature rather than proactive. The ammunition dump pouches are a classic example of that (my personal pet peeve). The inherent limitations of the revolver was only a part of the problem here, complicated by ridiculously outdated accessories. Strategy, tactics, and thought process is far more critical than the equipment on the belt. You can teach strategy, you can teach tactics, but you can’t teach thought process outside of time and experience, and a lot of close calls.

The Brick – the two way radio, the Motorola HT220 – was apparently not drilled into the minds of recruits as an essential life line to their survival. Getting on the radio early just might have been a significant element in avoiding this tragedy. Sadly, the lessons are slowly learned at the cost of the lives of street cops.

GREAT observations, thank you Sir! “A.D., not B.C.” HA!

I really do think that hoplophobia was a player in all of this. There’s a lot of stunted growth in the Deep Blue regions that influences officer safety.

I think it’s interesting how the pendulum on comms has swung too far the other way. Connolly and Gadell didn’t do enough talking, early on, but these days I think too many cops are talking too much on the radio, and at the wrong times.

Nowadays, we have no shortage of BWC video where officers are prematurely going to the radio, while their gunfight is still in progress. There’s a time to talk and a time to do, and I think too many officers don’t understand the balance. I wrote about it a few years ago: Shoot, Don’t Talk!

I just saw a video this week from Manchester, CT where this was demonstrated. An officer was shooting at an advancing suspect armed with a knife, and trying to talk at the same time. One hand on the radio, another on the gun. The officer apparently missed with six shots as the suspect advanced, then finally connected with the seventh. I think the radio was an unnecessary and dangerous distraction that prolonged this incident.

There’s a time to talk, and a time to do. Know the difference. Another lesson that Gadell’s experience helps to illustrate.

A tip from “Tuco” (played by Eli Wallach in The Good, The Bad and The Ugly): “When you have to shoot, shoot, don’t talk.”

Quoted in the linked article!

Thank you Mike. Another great article. Your careful and studious analysis of LODDs may save many lives in the future. If only one , it is worth the hard work you have put into these articles.

The times you describe in the two articles was a very dangerous and deadly period in history for American Law Enforcement Officers. The worst since that social experiment known as Prohibition.

I fear we are on the cusp of another period of great unrest and deadly times for all of America. The current conditions can not be sustained much longer.

Each of us who understand firearms and the safe and judicious use of them may be tasked with helping our friends and neighbors in the near future.

God please bless this country that was founded as one nation under God and return it to that state if it is Your plan.

I fear you’re right, Tony. I don’t know what the future holds, but I know where I’ll stand, and it comforts me to know that you and our greater RevolverGuy family will be there, with me.

I’d hope Campbell will at least spend the rest of his life imprisoned… even in Ohio we have cop killers looking at parole hearings after a couple of decades- for a capital crime! And we are a good bit more conservative than NY, I think. Sadly, we too frequently find rookies (not even off probation in some cases) riding together in my division. While I admire their enthusiasm they are certainly not learning caution and restraint.

Thank you for keeping Officer Gadell’s sacrifice in our consciousness, Mike. I found the points that you made (and S. Bond added to) about the decision-making environment of great interest. I hadn’t previously considered that the anti-gun culture of the area and the city of New York would color the thinking of NYPD, but it makes sense. You would like to think that “cops are cops”, but that’s not always the case when politics are involved, and bureaucrats are making the decisions. The fact that the commissioner and his boys would carry Glocks while prohibiting the rank and file from doing likewise is the epitome of poor leadership and a shameful example of forgetting from whence they came. Lots of lessons to be learned here.

The 70s and early 80s was a bad time to be the police in NYC. I’ve read several books about the BLA, none of which I still have, and none of whose titles I remember now, or I’d recommend them. I looked on your bibliography and none of them were there. (One of them was “Foster and Laurie,” and one of them was about the murder of Piagentini and Jones and was called “Badge of [something], and told of the manhunt for the killers. Robert Daley also wrote a book about that era of NYPD policing. I read that a long time ago, I don’t remember the title, and I couldn’t find it on Amazon. Maybe, if you’re interested, you’ll have better luck.) (The Daley book might be “Target Blue,” which is available on Amazon.)

When NYPD Capt. Frank Balz and Lt. Harvey Schlossberg, who sort of invented the modern art of hostage negotiation in the 70s, retired, they formed a training company. A friend of mine went to one of their seminars in the 90s, and told me they had this to say about the attitude of NYC’s bosses towards its cops: When an NYPD officer gets killed, they hire another one. But every bullet that a cop fires on the street costs the city $8800. (That was 1990s prices; it’s probably closer to 100 grand now.) So nothing happens till there’s a headline-making tragedy. That is, of course, on top of both bureaucratic inertia and the difficulty of making any big changes in a department that has 30,000 or so officers.

Regarding NYPD and speedloaders: Some time ago I read an article about the last NYPD officers whose revolvers were grandfathered in being told to turn them in and buy autos. (NYPD doesn’t issue pistols; every officer must buy his/her own.) There was an accompanying photo of about five NYPD officers in uniform, and their belts and Jay Pee bucket holsters looked like they’d been dragged behind a car, but the speedloader pouches looked brand new. It was a testament to . . . something.

Thank you Sir! I was unaware of those books, and REALLY appreciate the steer. I just found and purchased all three, and look forward to reading them.

The era from the mid-60s to early-80s was certainly very dangerous for our police. We lost more officers in the early-to-mid 70s than at any other time in our history. Assaults were through the roof. We hadn’t seen that level of violence and lawlessness since the late 20s to early 30s.

And here we are, right back in it. We’re not seeing as many officers killed now, but I believe that’s a function of body armor use, the fielding of trained paramedics/EMTs (which was only just beginning in the 70s), improved trauma/medical care, and advanced first aid/casualty care training and tools for cops. Absent those advances, I suspect we’d be seeing circa-70s numbers of officers killed. Maybe a little less, but close. Definitely closer to the 70s peak, than the low which followed in the 80s, 90s, and early 2000s.

We’ve never had great data on non-lethal assaults on police, and the records from the 60s-80s are pretty poor, but I suspect we’re seeing a comparable number of assaults on police today, too. We still don’t track assaults on officers very well (LEOKA is very incomplete), but I think we’re operating close to 70s numbers—again, maybe just a bit shy of them, but close.

Before the madness of 2020, I was warning cops that the era of the 60s and 70s was on its way back, and they would be wise to study the history of that time and the lessons learned. I was a presenter at national and state level conferences, and more than once I had a young officer give me a funny look when I told them they needed to be ready to defend their police station from attack, or deal with massive urban rioting, or elevated snipers, or radical revolutionaries.

Well, the succeeding years have borne all that out. Welcome back to the 70s, and buckle up. It’s gonna be a rough ride, especially because the greater public isn’t supporting the police like they did back then. If we had 70s-era courts, a 70s-era public, even a 70s-era media, we’d be in much better shape than we are now. This will get worse before it gets better.

That’s a big part of why I think these analyses of older events are still worthwhile. There’s a lot of gold to be mined in these older shootings, much to be learned.

Switching gears . . .

I think I saw the same photos you did, of the older NYPD officers transitioning to the autos. There was a distressing number of dump pouches that were still on those exhausted duty belts.

I did some more research. The Piagentini and Jones book is called “Badge of the Assassin,” by Tannenbaum and Rosenberg. I read it when I was brand-new on the job and was eager to learn everything I could about LE. Then, after I retired, I found a copy in a used bookstore, bought it, and found it so depressing I got rid of it. But it is in fact a very good account of the times. (I should have kept it. Seems like everything old is new again.) (Except me. I’m still old.)

Indeed. The wheel turns.

I believe you’re right that the use of body armor and medical advances are probably primarily responsible for the lower number of LODDs now than there were then. (Many year ago I saw statistics that showed assaults were way up, but deaths were down.) How many times do you read that an officer was “shot in his ballistic vest”? A goodly number of those officers would have been killed without the vests. (Of course, being “shot in the vest” is no fun, either. Backplate deformation can cause serious injuries. I once had a short convo with a medically-retired Detroit officer who had taken a 12-gauge to the chest and his vest. He pulled up his sweatshirt, and he was scar tissue from nips to navel. Being “shot in the vest” for real is nothing like being “shot in the vest” in Hollywood.)

As for the funny looks you got from the young coppers, I always thought the bad times were coming back, too. I was fortunate enough that I started after the previous bad times mostly ended and retired before the new ones will start. And when you’re a prophet of doom and gloom, it sucks to be right, doesn’t it.

Sure does. Wish I could say that I read the tea leaves differently, but it seems pretty obvious where we’re going, because we’ve seen it before. Same story, minor changes in the details.

A couple of weeks ago a bank robber shot an officer in my division with a rifle. Hits were in the leg, pelvis, and chest. The officer survived, though it was very close. The surgeon said the decision to tourniquet and transport without waiting for an ambulance made the difference. A chest hit through a IIIA vest with hard trauma plate is no joke, but that armor also made a difference. Officer is expected to make a full recovery in time.

Thank goodness for that. We all lift up our prayers for this officer and their family, friends, and fellow officers. I know the path to recovery will be difficult, but I’m grateful you’re not planning a funeral. Be safe out there, Sir.

Mike, thank you for researching the murder of NYPD Police Officer Scott Gadell. Your tactful analysis of my brother officer’s final moments, although painful to relive, is respectfully appreciated. I’m not sure why I had to wait several days before reading this article, then I had to take a few more days before I could type up my thoughts. I wish I was as strong as Scott.

I was a field training sergeant in a different borough in 1986. Over a four year period I received 30-35 fresh recruits from the Academy every six months. It was my responsibility to continue their training as probationary police officers by applying their academy training in their uniformed patrol duties. On my Jay-Pee gun belt I wore my regulation dual dump pouch containing a 12 spare rounds of .38 SPL Lead SWC 158 grain (non-hollowpoint/ standard pressure) rounds for my S&W 4” Model 10 Heavy Barrel. I still carry that weapon today but with better self defense ammunition and qualify annually for purposes of LEOSA / HR 218.

In addition, I also wore a S&W Model 36 in an ankle holster. Before my promotion to sergeant I was an Anti-Crime officer, working in plainclothes. Often I had to use my personal auto, a 1971 VW Beetle (reimbursement was five gallons of petrol!) Anti-Crime work was fascinating and exciting. In that line of undercover work I always carried two revolvers plus a two pair of “unauthorized” speed loaders. Precinct A/C officers comprise about 5% of the department yet account for 80-90 % of all arrests. Unfortunately all Anti-Crime units were recently disbanded by NYPD. NYC openly loves criminals!

My rookie officers couldn’t carry speed loaders due to their probationary status and many couldn’t afford the cost of a second gun. In NYC, officers were required to purchase ALL of their equipment, including firearms. The relatively ineffective ammunition was supplied at semi-annual qualification because it was mandated. God help any officer caught using +P ammo or any unauthorized weapon of another calibre!

You touched on so many points that struck a chord with me that I’m not sure where to begin.

RADIOS: RMPs had all radios removed during 1982-83 and only portable Motorola (HT220) handheld units were issued. Often only ONE radio was issued per two man radio car. There were times I had to place officers on foot posts, in the South Bronx, without any radio since I didn’t have enough for each officer. I don’t know if Scott or his partner each had a radio.

Sometimes heavy radio traffic prevents / blocks urgent messages. Three or four precincts shared one frequency.

FIREARMS: After four years of field training I transferred back to plainclothes in the narcotics division and was selected as one of the 200-300 LTs, Sgts or Dets in the Glock pilot project. NYPD clearly stated: Patrol Officers Need Not Apply.

The three day semi-auto transition course consisted of 800 rounds and was followed by quarterly qualification scores of 80% or better.c

Show up one week late or fail by one point and your Glock and the one spare magazine was confiscated. No forgiveness for tardiness or remediation. Yes, only one 15 round spare magazine was authorized. Those 9 mms were loaded with truncated cone FMJ ammo which did a helluva job zipping clear through perps. Just ask my XO would had to investigate a Brooklyn shooting where 11 of the 14 rounds exited the bad guy. The only recourse for those unfortunate few who lost their Glocks were to resume carrying their six shot revolvers.

At least, the pilot project was on track to prove the Department’s point: no need for semi-autos to fight crime in a city with over 2,200 homicides per year. Officers in the Firearms & Tactics Section (FTS) confided in me that the C.O. bitterly wanted the Glock pilot program to fail miserably. Word has it that he advocated for six round magazines! If it wasn’t for P.O. Gadell’s terrible murder, the exposure of “Out of Town Brown” and P.C. Ben Ward carrying personal Glocks, the pilot project would never have seen the light of day. The hypocrisy by the NYPD brass was truly astounding and may have cost many an officer their life. Another lesser known example of double standards by Dept. brass, in the early 1990s at one on my quarterly Glock 19 qualifications an unloaded H&K MP5 was passed around. Since sergeants in OCCB were the first ones through the door while executing search warrants, someone in FTS wisely felt we should have 32 rounds of 9mm handy since the Cocaine Cowboys had oodles of exotic firepower. Naturally, that idea was short lived. Only the bodyguards for the Mayor and P.C. were issued those MP5s.

I’m probably not hiding my rage and anger at those who cowered in 1 Police Plaza very well.

I was present at a shoot out were both officers in an RMP ran completely out of ammunition. My chauffeur and I then utilized our dump pouches to recharge their revolvers. Minutes later we were engaged in a running gun battle with the perps who had commandeered their stolen RMP. Another officer was killed during the pursuit and several seriously injured on the Grand Concourse just north of Yankee Stadium. Unlike us, those perps never ran out of ammunition.

EQUIPMENT: I believe Scott’s father was interviewed on television holding a $10 speed loader asking the reporter/ Mayor / PC if this forbidden device could’ve saved his son’s life? A few weeks later the department reluctantly allowed speed loaders, at the officer’s expense.

A few years earlier rookie officer had the audacity to ask “why aren’t we allowed speed loaders?” I vividly remember the FTS instructor derisively referring to “Jiffy Loaders” as ridiculous. I kept my mouth shut, but I carried them anyway!

The Gadell family is correct about the “Crouch and Turn” method for reloading. Sometime in the late 1980s revolver training was re-taught. Turning to one side to make yourself a smaller, narrower target was suddenly discouraged. As I recall, the reasoning was that many more officers wore bullet resistant vests and a hit in the front (hopefully in the vest) was preferable to taking round in the exposed, unprotected flanks. Kevlar panels (10 layers only) were donated by Police Foundation, a charity organization of major NYC companies. Officers had to purchase the fabric carriers to hold the panels. NYPD wouldn’t even provide vests!

Apparently, I still use a deep crouch and isosceles platform during my LEOSA qualifications, because so many instructors here in the South have commented on my stance. They’re also intrigued that in addition to my Glock 23 I also qualify with a S&W .38 revolver.

I believe PC Bratton deserves credit after learning that P.O. Arlene Beckles had her five shot, off duty revolver run dry when she took action during a violent armed robbery in a beauty parlor. I heard through channels that PC Bratton was mortified when he was informed that only one percent of the department were allowed to carry Glocks. You may remember that Chief Bratton, when in charge of LAPD, authorized patrol rifles after the Bank of America robbery. A film called “44 Minutes” depicted that watershed event.

44. Coincidently, forty four NYPD officers were murdered during my time on the job. I attended many of those funerals. To this day, hearing “Amazing Grace” still brings back those dreadful memories of Inspector’s Funerals.

I continue to pray for P.O. Scott Gadell and his family. Scott’s valiant sacrifice helped make this world safer and undoubtedly brought about positive changes for his fellow officers.

Mike, the lessons you bring to light ought to be required training for current law enforcement officers. Your father must be awfully proud of the service you’ve rendered to our nation and to those who are the tip of the spear safeguarding our society.

That was some incredible reading – thanks for sharing your insights. I’d heard about the limited radios or exhausted batteries still in use before, and it’s an excellent point that their transmissions were jammed out given the amount of radio traffic on that division if they actually did try to put something over.

I knew I’d heard of that stolen RMP, Grand Concourse shootout before. I believe that was in the incident in which Housing PD Officer Gary Peaco was killed in an RMP collision. Video footage of that scene was posted in the last couple of years on YouTube. (This channel has an untold amount of archival/news establishing footage from the era as well.)

Zach, thanks for sharing the video link of the aftermath of the robbery/shootout/chase of stolen RMP 1606/ resulting in the death of P.O. Gary Peaco. I was the first sergeant to respond to the 10-13. What a terribly tragic day.

Like Officer Peaco, I also had young twins.

I attended his funeral and often wonder how his wife and children fared after he was laid to rest.

The mention of his excellency, Dr. Lee Brown, a/k/a Outta Town Brown, by you and Mike has prompted me to bring up his abysmal record as head of Atlanta P.D. where, among other things, he is attributed with the decision to nix the use of hollowpoint ammo in the .38 Special revolvers as a deference to optics.

I was still working in Michigan at the time, and when I heard (and read) about it, I could only sympathize with officers who had to work under this overeducated ( fill in the blanks ). We were already using the .38 Special LSWCHP +P in revolvers chambered for .38 Special (or .357 Magnum). Many years later when I came to Georgia, his legacy still lingered on with many at APD.

Apparently higher education among police brass becomes a substitute for common sense and reality. This dumbness appears to happen with far too many who attend the FBI academy, FLETC, and universities to get that speshul edumakashun, and suddenly become xpurts.

I’m thinking of a few prominent examples from today’s headlines—folks who have left a trail of destruction behind them at a host of agencies, but still continue get hired elsewhere. Rhymes with Magnus and Acevedo.

Opa, thank you Sir. I sincerely appreciate your kind comments about my work, and I’m genuinely humbled. Very humbled.

I prize the exceptionally valuable contributions you made to this story in your personal interviews and your comments, and thank you for them. I’m a little embarrassed that I hadn’t thought to suggest the radio communication could have been blocked, since it’s commonplace in my own experience, but I’m grateful you addressed that possibility, as well as the shortage of portable radios. Either one of those scenarios is just as likely to explain the absence of timely radio traffic.

I was unable to confirm whether or not Officer Gadell was in possession of a backup gun. I only knew that he didn’t use one to defend himself, so I had to leave that question unresolved. Your explanation that rookies were frequently unable to afford one is important, and may very well explain why Officer Gadell didn’t use one.

Thank you also for the valuable confirmation about the crouch and turn method of reloading that was being taught by NYPD. It was extremely helpful to validate the concern from the family, and explain how Officer Gadell may have been following his training when he turned his side profile towards Campbell, as he reloaded. We all know that people are likely to revert to prior training and experience, under stress.

I’m always grateful to have the opportunity to salvage something useful out of these tragedies, but I’m also aware that these detailed analyses can stir up some powerful emotions in friends, family and fellow officers. I regret any sadness or pain my story may have caused, but hope it’s more than offset by the benefit of educating contemporary and future officers, so they can avoid the same mistakes. I’m particularly grateful to you for sharing such detailed, helpful information, knowing that it wasn’t easy for you to think and write about some aspects of it. We owe you our gratitude for that, and join you in praying for the friends, families and fellow officers of those who have been injured and killed in the line of duty.