Back in the days before drastic, fantastic, plastic pistols ruled the day, companies like Sturm, Ruger and Smith & Wesson were locked in a battle to decide who would be crowned the King of the double action revolver market. The distinction was important, as the double action revolver represented the largest segment of the commercial and law enforcement handgun markets.

The Great Revolver Frame War

At times, the battle got heated and marketing feathers got ruffled, much to the amusement of the gun buying community. In fact, there has probably never been a more entertaining marketing showdown than “The Great Frame War” of the early 1980s, which pitted a well-established Smith & Wesson against Sturm, Ruger, the new kid on the block. This is the tale of that Battle Royale.

The Dream Gun

While the climax came in the mid-1980s, the story begins in 1955. That was the year that Smith & Wesson released what was to become one of the company’s most successful designs ever, the Combat Magnum. The Combat Magnum was the result of a conversation between legendary lawman and gunwriter Bill Jordan, and Carl Hellstrom, the President of Smith & Wesson. In 1954, Hellstrom had asked Jordan for his thoughts on what the ideal law enforcement gun would look like, and Jordan didn’t hesitate to describe it in detail.

Jordan’s ideal gun would be a .357 Magnum, built on Smith & Wesson’s .38 Special, middleweight, K frame. It would have a heavy profile, four inch barrel with an integral ejector rod housing, and a cylinder with recessed chambers. The gun would be topped with a ramp front sight and an adjustable rear, to take advantage of the wide range of bullet weights and velocities in the .38 Special and .357 Magnum calibers. A lawman could select the load he wanted to carry, and easily regulate the sights for it–something that was not only more difficult, but also very permanent, on fixed sight guns.

At the time, Jordan had thought they were just “talking idly,” but Hellstrom was busy taking mental notes and a year or so later, he delivered the first production sample to Jordan, catching him by complete surprise. The delighted Border Patrolman and acclaimed exhibition shooter took it to a scheduled TV appearance, and introduced it to America as “the answer to a peace officer’s dream.”

And it was. The Combat Magnum, which became known as the Model 19 when Smith & Wesson assigned model numbers to all products in 1958, was a runaway hit from the start, and the factory had a hard time keeping up with orders. Even a full decade after its introduction, demand for the Combat Magnum far exceeded the supply, and the lawmen and shooters who had them were envied by their peers who didn’t.

Before the Combat Magnum, .357s were built on big, heavy frames (like the original home of the cartridge, the N-frame .357 Magnum, which was later renamed the Model 27), but the Combat Magnum was svelte. It was built on a .38 Special frame that was specially heat treated to withstand the stress of the Magnum load. It carried light, but hit hard, which is exactly what Jordan had wanted for a policeman who would carry it all day long.

Despite this successful formula, the Combat Magnum had a critical flaw. Like all K-frames, the barrel extension was too thick where it poked through the frame, and it didn’t allow enough clearance for the gas ring at the front of the cylinder. The solution was to shave a bit of material off the bottom of the barrel extension, at the 6 O’clock position, to provide enough room for the cylinder to swing closed. This flat made the bottom of the forcing cone a little thin, which was no problem for the lower pressure .38 Special, but under a steady diet of high pressure Magnum ammunition, it could crack.

This wasn’t a problem in the early years, because most shooters and agencies favored the less intense .38 Special loads, and didn’t put a lot of Magnums through the guns. But by the early 1970s, America’s beleaguered police had increasingly turned to the .357 Magnum as a solution for the ineffectiveness of the .38 Special 158 grain RNL loads that were the mainstay of law enforcement, and the Combat Magnum’s roots as a .38 Special began to show. Long term, continuous use of .357 Magnum ammunition was breaking guns, and even Jordan had to remind the public that, “the K-frame is perhaps a bit light to stand up under a steady diet of full charge .357 loads. Anyone wishing to do all his firing with maximum loads would do well to stick with the heavier frame of the original .357 revolver.”

The Combat Magnum was a dream, but it was a middleweight, not a heavyweight. It would have been unfair to call it delicate, but it wasn’t a tank, either.

Casting About For a Challenger

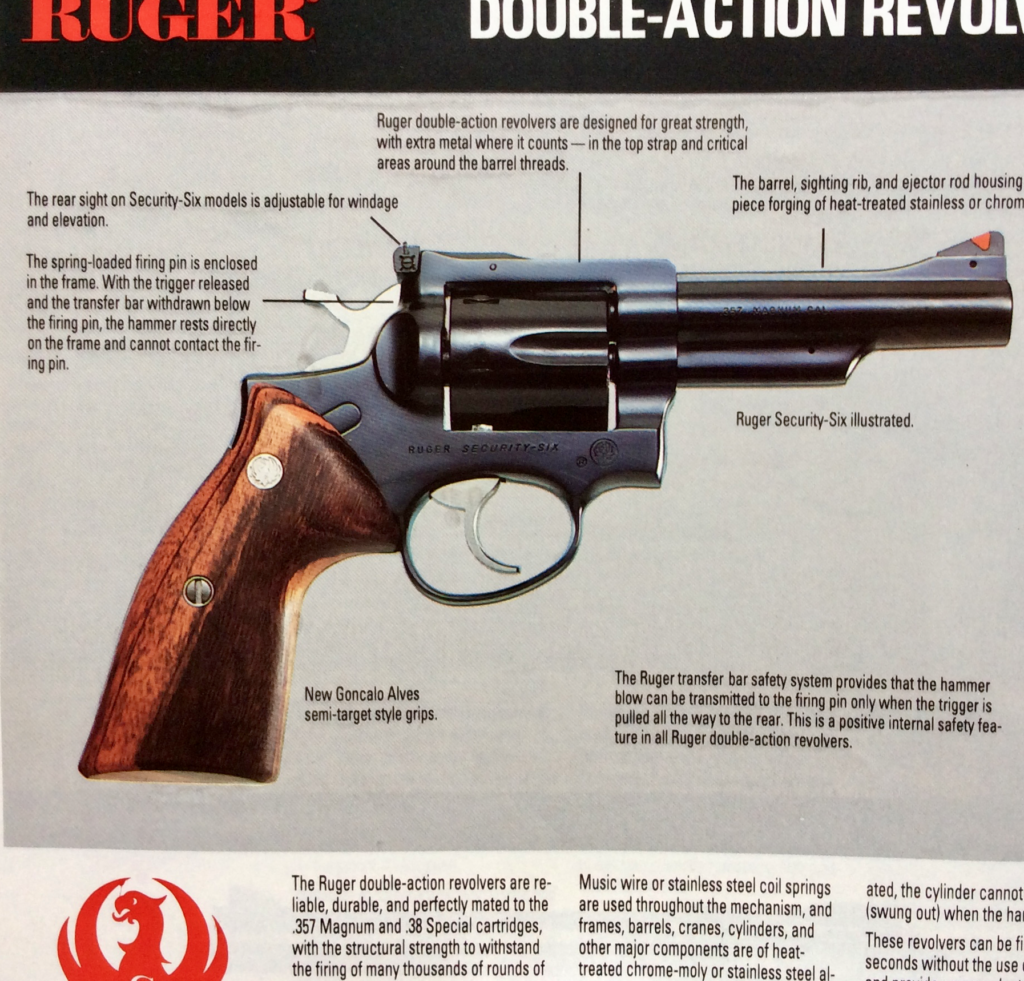

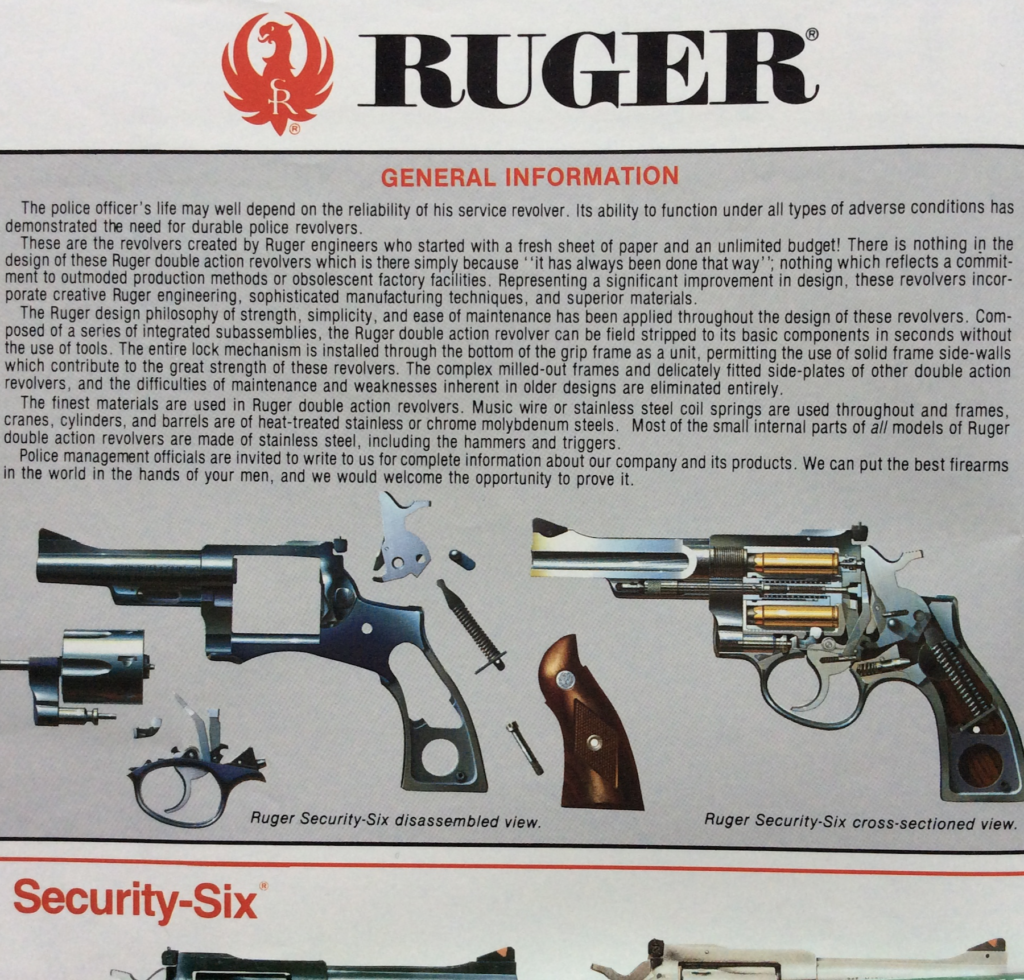

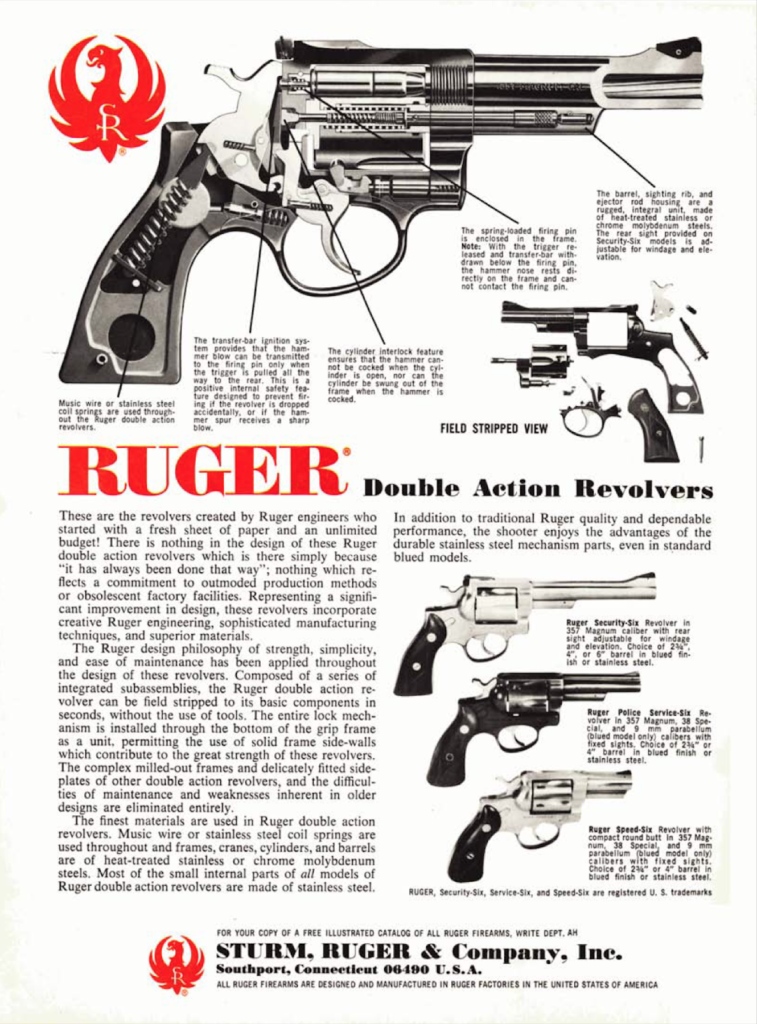

After Bill Ruger’s stunning success with semiautomatic rimfire pistols and single action revolvers, it was only a matter of time before he turned his attention to the lucrative, double action revolver market. In true Ruger fashion, he designed an innovative product that sought to correct the perceived flaws in earlier efforts, at a price that would undercut the competition. The result of his efforts, in 1970, was the Security Six (and its brothers, the Service Six and Speed Six). From the beginning, it was clear that the Security Six was designed to take the Combat Magnum head on, and it was a worthy challenger.

Like the Combat Magnum, the Security Six was a .357 Magnum on a medium-sized frame, with a thick barrel profile, an integrated ejector rod housing, and adjustable sights. Unlike the Smith & Wesson, the Ruger used a durable coil spring for the mainspring, and could be disassembled into its major parts and subassemblies using nothing but a coin, or the rim of a case. It also boasted a transfer bar safety mechanism, that made the gun drop safe.

The crowning feature of the Security Six, however, was the frame. The medium-sized frame of the Security Six was beefier in some areas than the Combat Magnum, particularly in the topstrap and recoil shield. Additionally, the Security Six frame was built as a single piece, without the removable sideplate of the Combat Magnum. In the Security Six, the entire action (minus the hammer and mainspring) was part of the trigger guard assembly, and was removed as a package out the bottom of the frame. No sideplate was necessary to access the parts.

Most importantly, the dimensions of the frame allowed the barrel extension to remain unmolested. There was sufficient clearance for the cylinder to close without shaving the bottom of the extension, eliminating the Achilles Heel of the Combat Magnum.

The Battle Is Joined

Ruger was quick to herald these features, claiming the Security Six could “be considered to be the first fundamental improvement in double action revolver design in more than a half century.” The constant theme in the advertising and marketing of the Security Six was its great strength, and its ability to fire an unlimited diet of Magnum ammunition, in a thinly veiled indictment of the Combat Magnum and its problematic forcing cone.

With the Security Six, Ruger not only challenged the supremacy of the Combat Magnum, but the entire business model of the Old Guard manufacturers, to include Colt. A Sturm, Ruger ad of the period declared:

There is nothing in the design of these Ruger double action revolvers which is there simply because ‘it has always been done that way’; Nothing which reflects a commitment to outmoded production methods or obsolescent factory facilities.

The first volley of the skirmish had been fired.

There was no doubt that Smith & Wesson needed to respond to this serious challenge, but how? In the years that followed, Smith & Wesson ramped up their advertising and tried to cement their longstanding relationships with influential police departments. They largely seemed to ignore the young upstart in their marketing and advertising, as if acknowledging Ruger’s thrust into the market would elevate the new kid to some kind of undeserved peer status.

Yet, the success of the Ruger product couldn’t be ignored. The Security Six was immediately received as a quality revolver that compared favorably to Colt and Smith designs. Furthermore, it boasted a lower suggested retail price, beating the Model 19 by roughly 15 percent, and the Colt Trooper Mk III by roughly 29 percent (1976 numbers). The Rugers sold well, and put a dent in Smith & Wesson’s bottom line. The marketing department could ignore them, but the accounting department could not.

Counterpunch

The counter to the Security Six came in 1971, when Smith & Wesson introduced the Model 66 Combat Magnum Stainless. After the 1965 introduction of the Model 60 Chiefs Special Stainless, the first production revolver in stainless steel, there was an instant demand for the beloved Combat Magnum in the new material. In bringing the Model 66 to market, Smith & Wesson knocked Ruger back on its heels, and swung the pendulum hard in the direction of Springfield, Massachusetts. Ruger responded with a stainless version of the Security Six in 1975, but the four years it took to bring that gun to market left Smith & Wesson in the lead without any serious competition in the booming stainless revolver market. And they weren’t done yet.

*****

Make sure to look out for Part II of “The Great Revolver Frame War”!

Sources:

Grennell, Dean A. Law Enforcement Handgun Digest, DBI Books, 1976;

Jinks, Roy G. History of Smith & Wesson, Beinfeld Publishing, 1977;

Jordan, Bill. “S&W Model 19: The Peace Officer’s Dream Gun,” American Handgunner Magazine, Vol. 2 No. 4-6, July/August 1977, https://americanhandgunner.com/classic-handgunner-editions/;

Supica, Jim & Nahas, Richard. Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson, Gun Digest Books, 2006;

Triggs, James. “Origins and Evolution of the Ruger Security Six,” American Handgunner Magazine, Vol. 1 No. 2-6, November/December 1976, https://americanhandgunner.com/classic-handgunner-editions/.

Thanks Mike,

Always walk away from your writings with a bit more knowledge than I walked in with!

Mike,

I have read bits of this saga here and there, never all in one place… And never that much info. I also love the old advertisements included- really helps bring the feel of the times. I’m looking forward to part two!

I can hardly wait for Part Two myself – trust me, you guys are going to love it!

Great info. I’m looking forward to the “Thick is for shakes and burgers” ad when we get to the L-Frames/GP-100 portion.

I kind of hope that we will see some of this frame war re-enacted. The LCR was Ruger’s first true response to S&W J-frames, and Ruger is now producing 7-shot GP100’s in .357. Since S&W has re-introduced the Model 66, I am really hoping Ruger will take that as incentive to re-introduce the Six Series (or possibly produce a new gun that fits the same smaller-than-GP100 6-shot .357 role).

I would argue that Ruger’s LCR/LCRx contributions to the modern, small frame revolver are already leaving the S&W J-Frame behind. Ruger continues to innovate and improve, and the LCR/LCRx line exemplifies this – smart design reflecting new thinking and for a darn good price point. I honestly can’t say the same about anything S&W has contributed to the field of late.

And I fully agree that a Ruger “smaller-than-GP100 6-shot .357” would be a highly welcome addition. I’d buy one in a heartbeat.

I agree that between the Ruger LCR series, the Colt Cobra (6-shot) and the Kimber K6 (also a six-shot), S&W has some serious catching up to do. Maybe this will be the spark of innovation and to echo someone else here, the start of another “frame war” which would be great for us in the market for revolvers!

Bring it – we all win!

Enjoying this series btw, and looking forward to the next installment. Well done.

I was just looking at the ads a little closer and noticed that they were uploaded in October of 2017, so thanks for the significant amount of time that clearly went into preparing this article (and, undoubtedly, all the others on the site, as well).

Greyson,

You’re absolutely right – Mike has had this two-parter in the works for at least eight months. I’d like to take this opportunity to also publicly express my appreciation for his hard work, and for being an all-around good guy. I am glad to have him writing here, but he sure sets the bar high for me!

I’m thrilled that this article is finally seeing the light of day. And I can’t wait for the “big reveal” next Saturday!

In regards to your other comment, I would love nothing more than to see a new Service/Security/Speed-Six series from Ruger, and I’m certain Mike would echo my sentiment on that matter.

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned (and no more spoilers!!!),

Justin

Dang! Thanks for the kind words everybody. I’m humbled. Honestly.

I’m eager to share Part Two next week, and think you’ll really enjoy it!

I’d LOVE to see Ruger bring back a true medium frame! In fact, if you look at the “About” page, I’m on record that they should bring the Six series back in a “Classics” line! The SP is close, but no cigar. We need a 6-shot cylinder on a medium frame, like the Six series used to be.

If you agree, tell Ruger via their “Voice of the Customer” program! They honestly listen to the feedback.

Wonderful story, Mike! The introduction of that iconic, original Combat Magnum must have come like a thunderclap! Wow, to suddenly have the inestimable .357 magnum available in a K-frame…

I like and own a fair number of both Ruger and S&W guns. My sense has always been that Ruger is the better value proposition, and that their guns have always been “over” built. S&W always seemed a bit more refined, with better actions, but poorer durability. Years ago when I was shooting Silhouette I quickly concluded that the hot handloads necessary for that game wouldn’t be very kind to my Model 29. So I switched to a Ruger Redhawk… which went on to digest umpteen zillion .44 magnum rounds without complaint or problem (but the week before a match I wouldn’t so much as _look_ at a Smith, lest its much cleaner single-action break jinx me).

I’ve grimaced at both companies as they fell afoul of political ill-winds, or (seemingly) hired one too many lawyers. Bill Ruger when he halted civilian sale of the collapsible-stock Mini-14 following the FBI Miami Massacre, and for the godawful legalese that has long adorned both the steel of his weapons and the paper of his owner’s manuals. And S&W when their various ownerships have tried to be “reasonable” with the anti-gun crowd… leading to that abomination of an internal key lock, among other things.

Mostly, though, I remind myself of the wonderful riches that these icons of American firearms manufacturing have brought us. And I look forward to whatever their next innovation might offer. Long may they reign!

Looking forward to Part II!

This soon-to-be GP100 owner eagerly awaits more! Excellent start here.

When it comes to the topic of S&W versus Ruger , I’d love to see an article on cast frames versus forged. Many times, people assume that Rugers are stronger than S&W because they have bulkier frames…but AFAIK much of that difference comes down to the fact that cast frames are not as strong as forged – and as a consequence must be proportionally larger.

Patience . . . ; ^ )

Dang I just found this page. HT to Say Uncle. Great article. I am a new fan.

Actually HT to Active Response Training, who I got to through Say Uncle.

Thanks, Dean! Always glad to hear someone else is enjoying the blog!

I always enjoy the artiles on Revolverguy.com

Well written and very informative. I check in every week!

I see some of the source material was

Dean Grennell.

He was one of the “old time” writers

I really liked. His writings about

reloading were really entertaining.

I never met him, but he seemed like a neat guy and a gentleman from the outside. He edited the annual that I referred to for 1976 pricing. I always liked reading his work back in the day, and he frequented the range that I shot at as a youngster.

I lived, bought and shot through this revolution. I got one of the first Ruger SSs in my hometown. I still own it. I have owned 50 S&Ws to every Ruger I had and still enjoy them. The Rugers struggled for market place in the DA guns in the south. Still today, when you say revolver in our part of the world folks think S&W.

Hi, just wanted to say good writeup. However, the Security Six was actually the last of the lineup to be released. The Service Six was the first one, then the Speed Six, and finally the Security Six came in 1974. At least according to this article:

https://www.guns.com/news/2013/03/25/the-ruger-six-series-wheelgun-muscle-70s-style