Or . . . The Day the Man, Who Killed the Man Who Killed Jesse James, Picked a Fight with the Wrong Oklahoma Police Officer

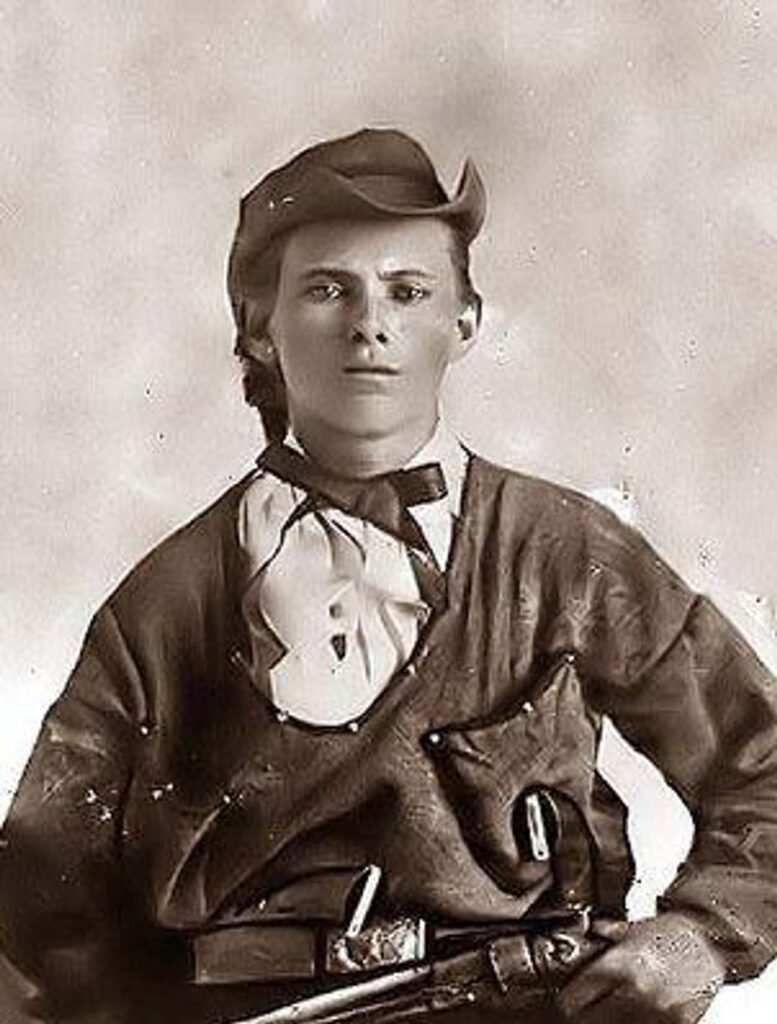

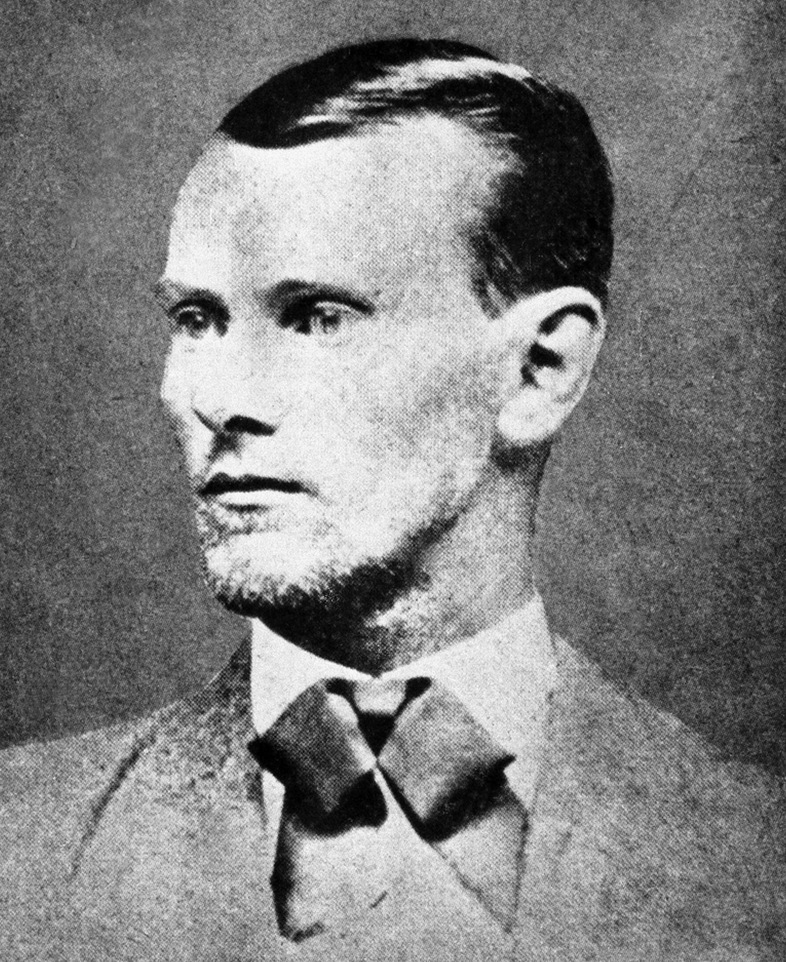

Jesse Woodson James was born on the 5th of September, 1847 and was a happy arrival for his parents and older brother, Alexander Franklin (“Frank”) James. None of the family ever dreamed that Jesse would become one of the most notorious American outlaws ever.

The James family had a farm in Centerville (later, Kearney), Missouri, in Clay County. They were soon joined by another family that moved to Missouri and settled in Clay and Jackson County—The Youngers. Henry Washington Younger and his growing family were considered wealthy land owners. Out of the family of 14 children, four of the boys also gained notoriety as criminals, including Thomas Coleman Younger, who became close friends with Frank James.

FAMILY CHANGES

In early 1850, Frank and Jesse’s father, Reverend Robert James, informed his wife Zerelda that he was joining the gold rush to California. He made it to Hangtown (Placerville, California) on July 14, 1850. Shortly after he arrived, he contracted dysentery and died.

With three children and a farm to care for, Zerelda’s period of mourning was short. It was not long before she was remarried to Benjamin Sims. It was not a happy marriage. In January 1855, Sims died in a horse accident.

Thinking the third time might be the charm, Zerelda married again to Doctor Ruben Samuel on September 12, 1855. This marriage was successful, and the boys grew fond of their stepfather. That marriage added four more children. Things were good in the Samuel household, but storm clouds were gathering in America, and the nation would soon plunge into violent strife.

CIVIL WAR

Many issues contributed to this strife. The main issue was that of slavery. However, conflicts over state’s rights, government oversight and other differences continued to divide the country, until open warfare broke out all over the nation. In the middle of this chaos, there was no region more violent than the Kansas-Missouri border area.

Eleven states seceded from the U.S. and raised armies to counter the Union’s efforts to strengthen their military forces. The war was the worst this country had ever faced, and remains so. Historians are reconsidering casualty numbers and some estimate that over 700,000 men on both sides were killed. While most of the fighting back East was conventional, with large armies clashing in huge engagements, a different sort of conflict was occurring in the Trans-Mississippi theater of war. A very brutal kind of war was waged in Missouri and surrounding states.

CENTRALIA MASSACRE

Guerrilla warfare, waged by unconventional forces on both sides, caused blood to flow freely throughout the Missouri countryside. Bands of these fighters would sometimes join with conventional forces in regular engagements, but hit and run fights were more their style. Their weapons of choice were revolvers, with the Colt 1851 Navy model being one of the most popular.

Guerrilla fighters would load their belts with up to four revolvers, and might have two to four more in saddle holsters. Switching an empty revolver for a loaded one sure beat trying to reload a front-loading revolver from a seat on a horse. Maybe we should change the term “New York Reload” to “Missouri Reload.”

One battle involving guerrillas and regular troops occurred in September of 1864, in and near the town of Centralia, Missouri. Several bands of Confederate guerrillas joined together, under the command of William “Bloody Bill” Anderson, to assault this town. While engaged in their plunder, a westbound train approached. It was halted, and the guerillas found 25 unarmed Union soldiers (who were on furlough) aboard. The soldiers were removed from the train and ordered to undress, then all but one of them were shot and killed. Bloody Bill certainly earned his nickname that day.

After they finished pillaging the town and murdering the unarmed troops, the guerrillas moved out of town to join the rest of the Confederate irregulars, camped along a creek, south of town.

A Union force of mounted infantry, under Major Andrew V. E. Johnston, arrived to discover the horrific scene. When he found out the guerrillas were a short distance ahead, he left Captain Theiss and his Company H behind in Centralia, and led the remaining force of 115-120 men in pursuit of Anderson’s band, which numbered 80 men, according to townsfolk.

As Johnston and his command topped a ridge about two miles south of the town, they saw a line of mounted bushwhackers emerge from a tree line at the end of the field. Johnston ordered his men to dismount and every fourth man became a horse holder and moved the mounts to the rear. As his men formed into line with their single shot Enfield rifles, Johnston ordered them to fix bayonets. Then his blood chilled as a large line of mounted men came from the woods to the left and another large group from the wood line on the right. At that moment, Anderson ordered a charge. A short, but very deadly, fight then occurred. A few of the Union horse holders fled back to Centralia, but Johnston and his command on the field were all dead, some mutilated. Some counts place the dead in the field at 120+, with only three guerrillas killed. The revolver made the tactical difference in the fight that day.

POST-WAR BANDITRY

After the war ended, many Confederates were reluctant to end their efforts. Guerrillas Jesse James (who was credited with killing Major Anderson, at Centralia), Frank James, Cole Younger, and others decided to keep fighting by means of robbing banks and trains in Missouri and surrounding states.

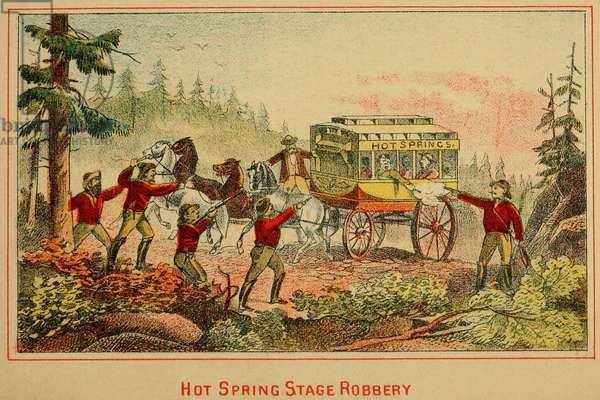

Hot Springs, Arkansas has always been a popular destination for tourists. Railroad access to Hot Springs was late in coming, so in the early years, visitors would ride the train to Malvern, Arkansas, then ride a stage coach to the Valley of Vapors, the Hot Springs.

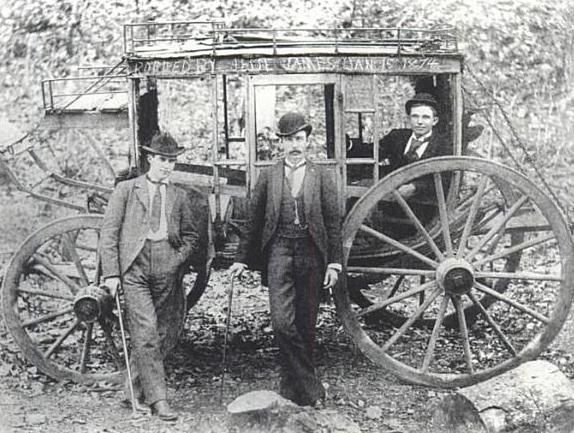

On January 15th, 1874, a concord coach and two light road wagons of the El Paso Stage Company left Malvern for the trip to Hot Springs. In addition to the employees there were eleven passengers. Making good time on the 24-mile trip, the stage stopped at Gulpha Creek to water the horses. Five men rode by eastbound on horseback. Each man wore an old army great coat and was heavily armed. After the horses drank their fill, the passengers loaded up in their wagons and started the last, five-mile leg of the trip.

The group had only gone about a half-mile, when the same eastbound riders they had passed rode up, stopped the coaches, and ordered the passengers to dismount. The robbers proceeded to relieve the passengers of all their cash and valuables, while one of them selected a horse from the stage hitch, saddled him, and took him up the road with his other mount. After the bandits finished emptying pockets, they asked if any of the victims had served in the Confederate forces. One man–George Crump, from Memphis–said he had, and according to reports, he was given his money back.

John A. Burbank, the former governor of Dakota Territory, was another one of the robbery victims. He lost $840 cash, a diamond stick pin, and a gold watch. He was also carrying a satchel of documents and papers.

The leader of the gang took the satchel and looked through the papers. He looked up and said to his men, “this man is a detective. Shoot him.” In the blink of an eye, three revolvers were pointed at Mr. Burbank. But, before they could pull the triggers, the leader told them to stop and said, “I believe he is alright.” The robbers then mounted and rode away. Some reports credited their take to be roughly $2,200.

The stage went on to Hot Springs. The Garland County Sheriff, J. J. Sumpter, organized a posse and began searching for the robbers. Shortly after dark, the robbers stopped at a farm house about 14 miles northeast of Hot Springs, owned by a man named Houpt, and exchanged a horse for a fresh one (it’s interesting that two other men named Houpt served as sheriff of Garland County — Reb Houpt, in 1892-1898, and Jake Houpt, in 1908-1910. Jake Houpt was killed in the line of duty August 20, 1910).

The band of robbers continued in a northeasterly direction, being spotted in White County, near Bebee. They would frequently stop for meals, or rest, at residences along the way, leaving payment for same, as was the habit in those days. Each sighting produced the same general description of the men, their mounts and mostly their arms. Each was said to carry two revolvers, and there were two double barrel shotguns in the party, but no reports of rifles.

By now, the riders were some 200 miles from Hot Springs. On the 27th of January, they stopped and had their horses shod, then took dinner near the Missouri state line. After crossing into Missouri, they continued with their habit of stopping for food and rest. They had begun telling their hosts that they had fed the James Gang.

A NEW TACTIC

On the morning of January 31st, they were four miles south of Gads Hill, Missouri, a small village on the St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad. Gads Hill, named for Charles Dickens’ English home, had been the stop for a cordwood and charcoal operation. There were a few shanties, a train platform, and the former coal operation company store. There was no depot and the train would be flagged down should there be an outbound passenger.

The James Gang stopped for the midday meal at the Hamil home. Mrs. Hamil was a widow with several children. When the men finished their meal and left, each had left a five-dollar gold piece, except for the leader, who left a ten-dollar gold coin. One of the daughters, later in life, recorded her reminisces of that day, including the tips.

Several citizens of Gads Hill were sitting around the wood stove in the general store, waiting for the Little Rock Express. The northbound train had passed earlier. Someone looked out and saw five riders approaching. All were masked and heavily armed, with each man carrying a brace of Navy Colts (“silver mounted with ivory grips,” was the description given).

The small group of citizens watched the riders. They soon got a closer look when they were peering into the barrels of those Colt Navies, and were being asked to empty their pockets. One man, the storekeeper, didn’t believe in banks, and it cost him $700 or $800 that morning. He did have another $450 hidden in the lining of his coat.

The southbound Little Rock Express slowed as it approached Gads Hill. The engineer stopped the train when he saw a man with a red flag on the tracks. As soon as he did so, the five bandits boarded the train, took control of it and proceeded to rob the train, the passengers, and its crew of money and valuables. The conductor said that the robber’s toll was about $2,500, plus jewelry, watches, and revolvers. The gang exited the train, “borrowed” three saddle horses and fled in a northwesterly direction.

This ended Missouri’s first train robbery, but the James Gang continued on with their career of robbing banks and trains with great success until a failed bank raid in Northfield, Minnesota, which saw the death of two gang members slain by townsfolk, and the capture of three Younger brothers.

NEW BLOOD, BAD BLOOD

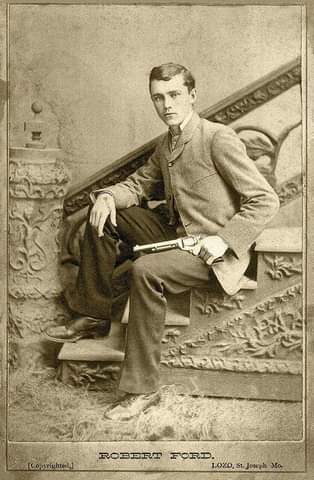

After the Northfield blunder, the James Gang began to rebuild. They were forced to recruit people that they didn’t know as well as those who had been with them for years. The new members often had less hands-on experience in the art of train and bank robbery. One or more of the potential recruits had been with the James boys a time or two, but their trustworthiness was still in question. Two young men, Bob and Charlie Ford, from Richmond, Missouri, were taken into the gang did some jobs with them.

Bob Ford, his brother Charlie, and another gang member later sought immunity, in exchange for the capture or killing of Jesse James. They met with Missouri Governor T. T. Crittenden and other officials, and all parties agreed to terms.

At the time, Jesse, his wife, and his two children were living in St. Joseph, Missouri, under aliases as the Howard family. Jesse was planning his next job and chose to use the Ford brothers in the robbery of a bank in Platt City, Missouri. Charlie and Bob stayed with the Howards in St. Joe for a few days before the planned robbery.

On the morning of April 3, 1882, “Mrs. Howard” cooked breakfast for her family and their two guests. After eating, “Mr. Howard” and the two guests moved into the living room to talk. After a bit, Jesse did something unusual–he unbuckled his gun belt with two revolvers and laid it aside. In the next few minutes, Jesse noticed a framed sampler, with a “God Bless Our Home” theme, was hanging crooked. He got a feather duster, pulled a chair under the sampler, then stepped up and began dusting it.

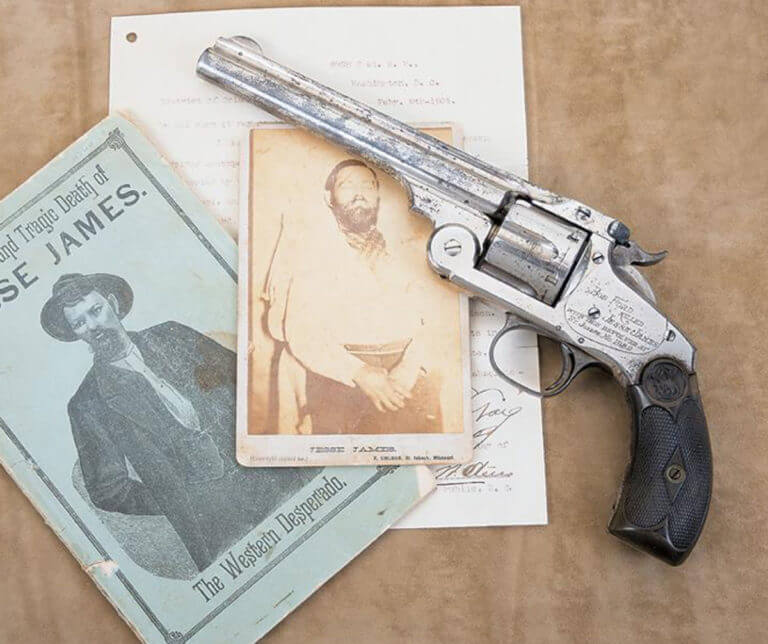

As he heard a very familiar sound–one he had heard all his life–of a revolver being cocked, he started to turn. Before he was able to turn, he was hit in the back of the head with a bullet from Bob Ford’s S&W Model #3. He fell to the floor, dead, as the Fords fled the house.

When the St. Joseph authorities responded to the scene, they began to inventory items in the house with the knowledge that some were stolen property. One of the items they found was the engraved, gold watch that belonged to John Burbank, the former governor of Dakota Territory, who had been robbed outside Hot Springs, Arkansas on January 15, 1874 in a stage coach robbery.

WHAT GOES AROUND . . .

Charlie and Bob Ford were charged with murder, tried, pled guilty, and sentenced to be hung. Their sentences were commuted by Governor Crittenden the same afternoon. They then began touring the country in a stage play enacting the killing of Jesse James. They were not well received.

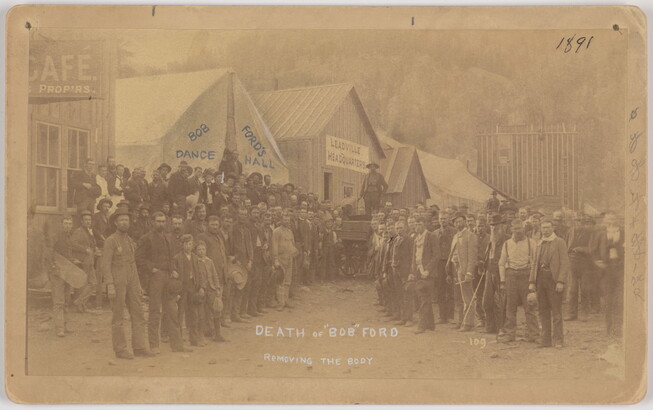

Creede, Colorado was where Bob Ford reached the end of his trail. He had opened a saloon/dance hall and was operating it in a large tent in the mining town. On June 8, 1892, Ford was at work getting his tent saloon up and running as a temporary replacement to his original location, which had burned recently. As Bob worked, he heard someone say, “Howdy, Bob” and looked up in time to see a shotgun pointed at him. The man holding the shotgun fired, and nearly decapitated Ford at the close range.

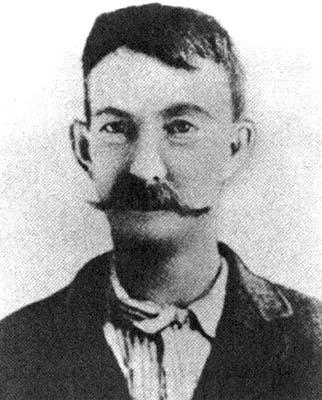

Edward O’Kelly, who killed Ford, was taken into custody and charged with murder. In the style of swift justice of the period, O’Kelly was tried and convicted in the month of July 1892 in Lake City, Colorado, and sentenced to life in prison. O’Kelly, who had worn a badge as an officer on the Pueblo Police force, and as city marshal of Bachelor, Colorado, was released from prison after ten years.

A CASCADE OF BAD CHOICES

After O’Kelly was released from the state prison in Canon, Colorado, he drifted back to Pueblo, where he was soon arrested for public drunkenness. When he was released from that charge, he left Colorado and traveled to Oklahoma City. He was arrested in Oklahoma City soon after he arrived, probably for the same charges of being drunk and a vagrant.

At this point in his life, O’Kelly was extremely angry with law enforcement for his “treatment.” Like many folks before and after him, he failed to realize he was the cause of his own problems–not the officers, that he blamed.

On January 13, 1904, at 9:00 p.m., O’Kelly was walking up West First Street, when he noticed an Oklahoma City police officer walking down the sidewalk in his direction. As the two passed each other, in front of the McCord-Collins Building, the officer said, “Hello, O’Kelly”.

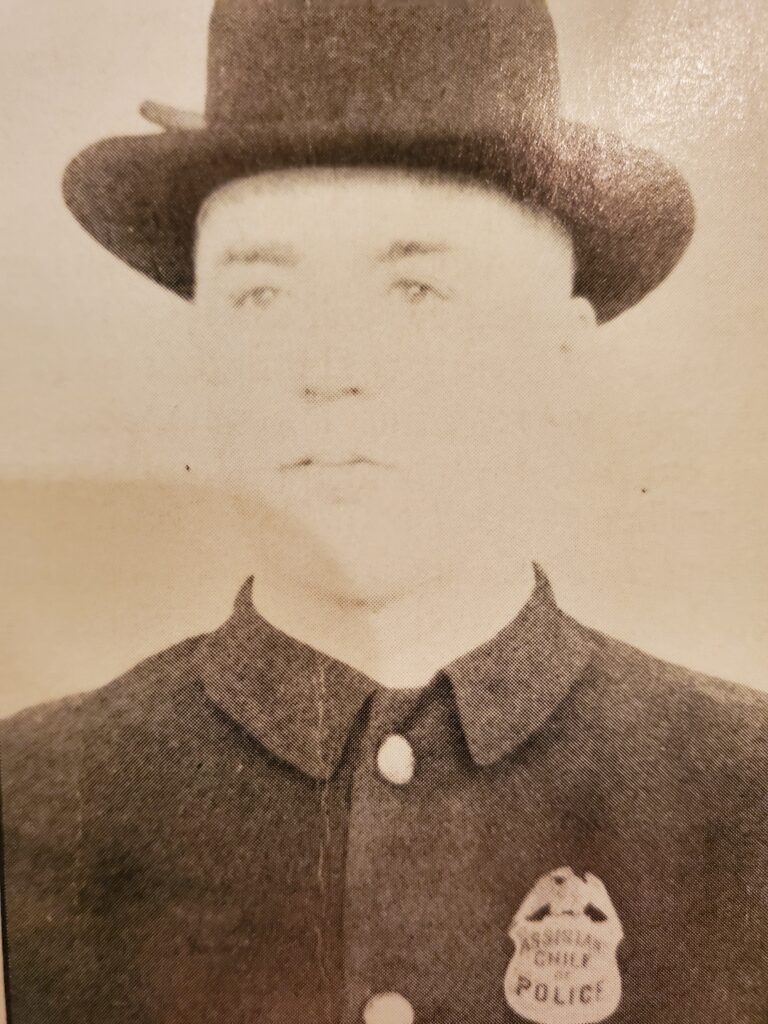

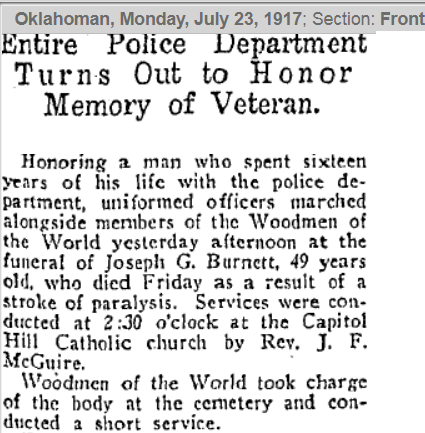

The ex-con pulled his Colt New Service .45 from a coat pocket and struck Officer Joe G. Burnett in the head with it. That began a lengthy life-and-death struggle that many folks who have worn a badge are familiar with. The first account of the fight that I read said the fight took 25 minutes, which does seem incredibly long. Other accounts that I have since read all seem to peg the duration at 15 minutes. The shorter time is more likely to be accurate, but however long it lasted, it surely felt like an eternity to Officer Burnett.

Burnett instinctively grabbed O’Kelly’s handgun with his left hand, and drew his baton and struck O’Kelly a couple of times. O’Kelly fired his revolver and the gases that escaped from the cylinder burned Burnett’s hand through his white glove. One of O’Kelly’s cronies rounded the corner and O’Kelly told him to shoot Burnett. The officer spun his assailant to put him between himself and the new threat. The other thug could not fire for fear of hitting his friend and eventually ran off.

In this phase of the struggle, Burnett dropped his night stick and drew his Colt D. A. .38. Both of the combatants fired, but missed. They struggled in this macabre dance down the street for nearly 100 feet while hanging onto each other’s gun hand. Shots continued to be fired with no disabling strikes.

Burnett began calling passersby and witnesses to the struggle to help him, but no one did. O’Kelly bit the officer’s ear. At that point, the ex-con must have been counting shots or heard clicks on the empty chamber of Burnett’s revolver. O’Kelly let go of the gun hand of Burnett and drew his second revolver, a .44 S&W from his other coat pocket, and fired another shot that missed. The life-and-death struggle continued until a brave railroad employee, A. G. Paul, entered the fray and grabbed O’Kelly’s hand holding the .44. That gave Burnett the opportunity to draw his second revolver from the small of his back. He then fired one shot into O’Kelly’s head.

The fight was over. The man, who killed the man who killed Jesse James, was dead.

LESSONS AND WARNINGS

Despite the time that has passed, there are many similarities between the world of the late-1800s to early-1900s, and today’s. Every day on the streets of this country there is probably at least one incident where an officer is engaged in a life-and-death struggle with a person he is trying to arrest, just as Officer Burnett was.

The lessons from Officer Burnett’s struggle are timeless, and we would be wise to heed them, as people who carry guns in and out of uniform.

In this case, the criminal was armed with multiple guns. The “Plus One” theory of policing applies here: Always expect one more gun, one more suspect, one more surprise. Stay alert for additional threats and problems, and don’t get comfortable thinking you have everything covered.

A backup gun was a lifesaver for Officer Burnett. Should we be calling it the “Oklahoma City Reload?”

Situational awareness and weapon retention are critical. In every encounter an officer has, there is a firearm involved. He brought it to the fight, and many times the person fighting the officer has strong intentions of taking the officer’s weapon and using it against him. I think it has happened to a large percentage of officers during their careers, sometimes with very tragic results. The risks are the same for citizens who carry concealed—your gun can quickly become “our gun,” in a close contact fight.

Fitness is vital, and can’t be emphasized enough. Police work is sedentary to a large degree and often involves unhealthy eating habits. The 90% of boredom punctuated by 10% of terror can vividly illustrate the need for keeping fit. This is true for anyone who may find themselves in a life and death physical struggle.

Don’t give up. Poor victim selection worked against O’Kelly that January evening in Oklahoma City, because he ran up against a man who would not quit, who fought that good fight until the end.

Respect, honor, and remember our lawmen. There are libraries full of books about Jesse James, but how many books have been written about Officer Joe G. Burnett?

Finally, an important warning: The promise of swift judgement and certain punishment has diminished greatly in our time. In fact, it’s darn near disappeared. This is a big part of why our world is infested with rising crime and violence. “Soft on crime” policies will only encourage more violations of the law, more criminal violence. We need to restore a respect for law and order, and the swift punishment of the guilty, or the result will be anarchy.

God bless each of you, and keep you safe in this world we live in.

*****

references

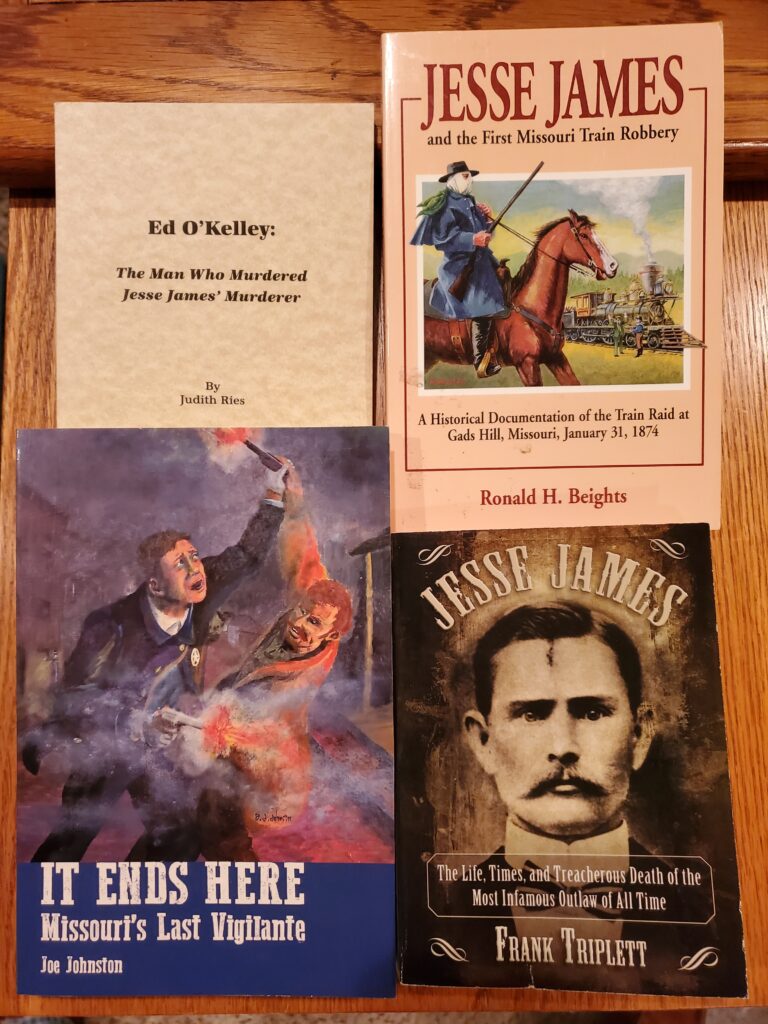

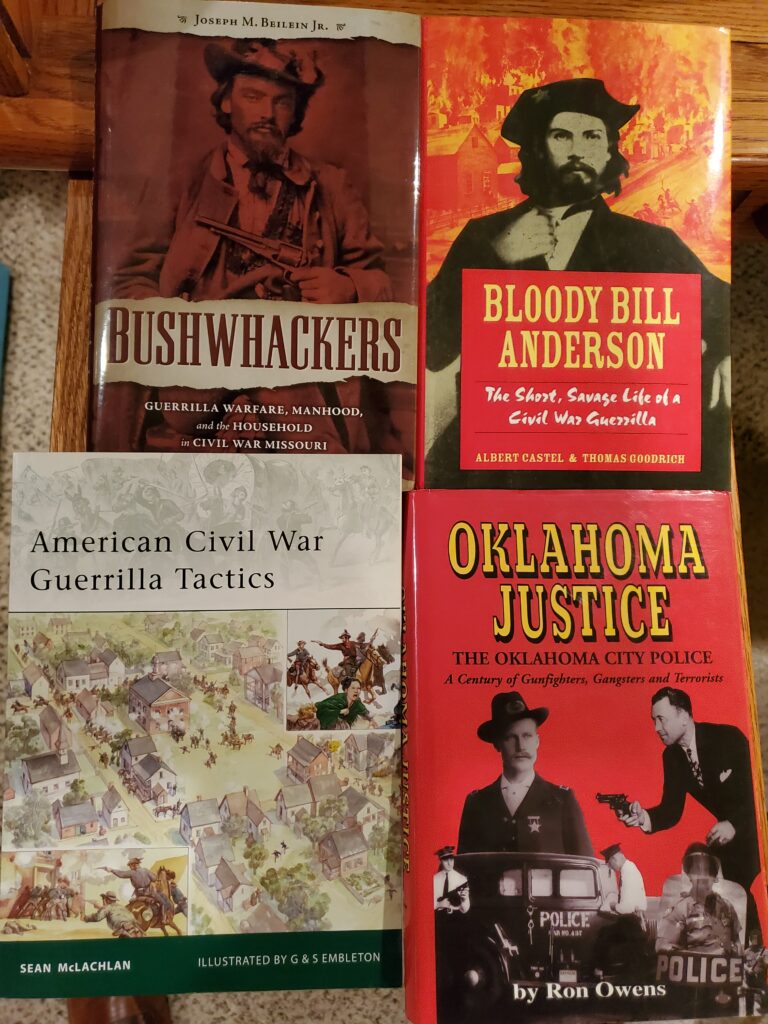

The following books will interest RevolverGuys who would like to learn more about the history of these events:

Thank goodness Officer Burnett had his OKC reload! I carry one every day and encourage every officer to do likewise. I gotta say, 15 minutes of fight sounds like a nightmare. I get into a two minute fight I’m tired… but I’m not in very good shape these days. Sedentary job and all.

That adrenaline dump can gas out ANYbody, in just a minute or two!

Thanks for sharing that history Tony. Well done!

Jesse James, too, failed the situational awareness test in the end. Not that he was any loss to society, despite the efforts of generations of writers and Hollywood directors who tried to convert him into a late 19th century Robin Hood. Indeed, many decades of American popular culture’s twisting bad guys into heroes may have added to our current “soft on crime” woes.

Great article by the way. I never heard of Officer Burnett and his nightmarish battle with mad dog O’Kelly.

Thanks, Tony, for this excellent look back into a violent time of our past. Lots of lessons to be re-learned, here. NY Reload, Missouri Reload, OKC Reload, there seems to be a trend here that the good guys should heed…

Tony, Thank you for that rather intense history lesson. Seems the criminals get the fame, and the police that hunt them down get a back chapter in the book of oblivion.

Hidden within your excellent account of events lies the lesson that if you think you have all your bases covered, you don’t ! Legal gun toters need to keep their head on a swivel and have a situational awareness of major airport radar. It’s difficult to do all the time, and even the best have gaps in ‘coverage’ – but we have to be lucky 100% of the time; the bad guy only has to get lucky once.

My thanks to each of you fellows for your kind comments. This day story had a lot of twists and turns. It was interesting to me as I read and researched more about the characters and events of this story.

Best to you and yours.

Tony

Around the mid-nineties, I embarked on a grand tour of the U.S., traveling rough in my small pickup. Because of having read several histories of the James-Younger Gang and the Youngers’ cousins, the Daltons, I veered off to explore my version of the Midwestern outlaw trail.

Starting at Coffeeville, Kansas, where the Daltons in 1892 were shot to pieces by the townsfolk for trying to rob two banks at once, then dropping by the James family farm in Missouri, I ended up in Northfield, Minnesota, where in 1876, while also in the process of robbing a bank, the James and Youngers were badly shot up by angry inhabitants.

Today, very few American citizens, if any, would engage in a gun battle with bank robbers since bank deposits are federally insured against all kinds of disasters, but before 1933, customers had no such protection. If a bank’s money were stolen way back then the depositors would not be reimbursed. Facing potential financial ruin if their bank was being cleaned out by robbers, the enraged locals often armed themselves and annihilated the bad guys. My assumption is not many outlaws tried to rob those banks again after such debacles.

You’re a good “straight man,” Spencer! Tony has an article forthcoming on this very topic!

A great story as usual. There is a typographical error where it states that Zerelda’s 3rd marriage was in 1885, it was in 1855.

Good eye Tec’s Dad, I will blame on my Editor or my Chief Assistant, then again it might just be my old fellerness.

Thank you Sir.

But but but . . .

That photo with the nightsick and a PLASTIC revolver!

Museum display, I think. Sometimes they get funny about having real guns on display.

Nope, I am guilty of sticking that chalk SA in the image. It was the only Colt ” revolver” in the house.

It bothers me too but sometimes you just have make do.😉

It’s strange that such a respectable cop would choose to be buried next to the man he killed. Rather than with family or the Territorial Lawmens Association he’s buried next to the man that got him his Assistant Chief job. Ed O’Kelly is buried in a pauper(pine box) grave in a cemetery reserved for dignitaries??? I find a bad smell all over this story. His reward for killing Bob Ford was stolen by…..