If you’ve been around RevolverGuy since the early days, you may recall this particular RevolverGuy got his start with a Ruger Single-Six. That wonderful little sixgun was the tool I used to learn the fundamentals of shooting handguns, and it will always occupy a special place in my heart, and in my collection of revolvers.

That collection recently expanded by one with the addition of the Single-Six’s new little brother, the Ruger Super Wrangler. I’ve been enjoying some one-on-one time with this new sixgun lately, and I’m excited to share my thoughts about Ruger’s newest, thumb-cocking rimfire with you, and explain how it compares to the other Rugers you’ve known.

So, grab your milk carton of .22s and a couple of soda cans, and let’s start off on this fun, little rimfire journey.

Roots

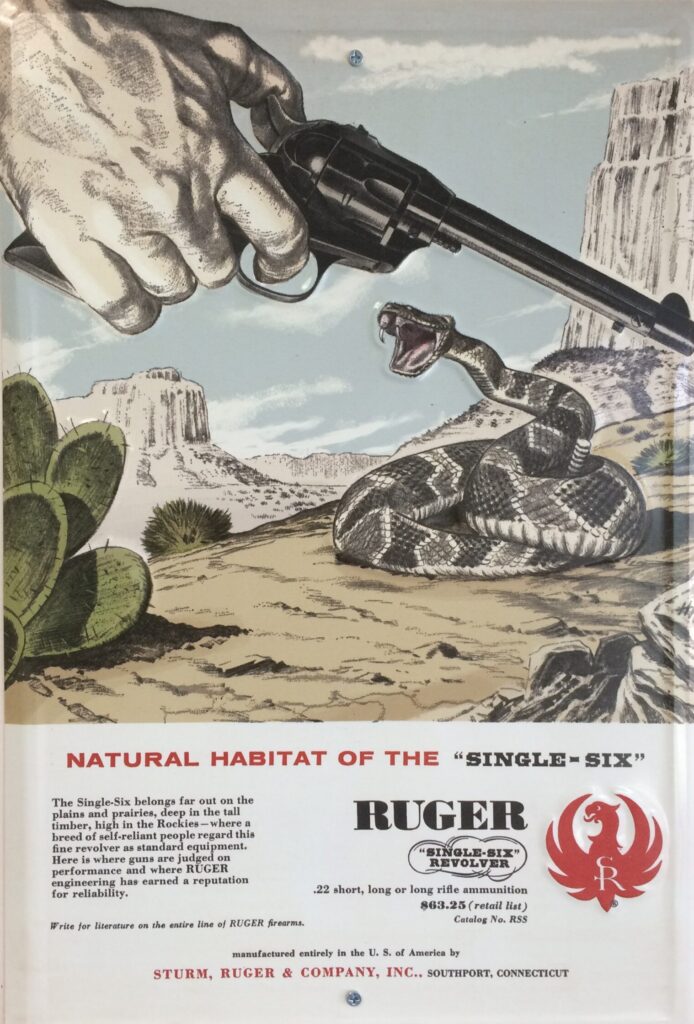

I suppose the place to start is with the big brother of the bunch, the Single-Six.

The Single-Six was Sturm, Ruger & Company’s second commercial design, following 1949’s semiautomatic Ruger .22 pistol that would later be renamed the Standard (which is now in its fourth generation). The first Single-Six was produced in 1953, and capitalized on the tremendous interest in “cowboy guns” that was being generated by the leading radio, television, and movie productions of the era. Chambering the gun (which resembled a svelte, Colt Single Action Army—the most popular “cowboy gun” of all) in .22 Long Rifle was a stroke of genius, as it made the gun affordable and fun to shoot.

The Single-Six, named after the 1920 Packard Single Six sedan (Ruger was a car buff, too), maintained the attractive styling and excellent handling qualities of the Colt Single Action Army, but improved on the design in important ways. The Colt’s fragile, flat mainspring was changed to a robust coil spring in the Single-Six, and the similarly fragile, flat, cylinder bolt spring was replaced by a much stronger, wire torsion spring in the Six. The Single-Six also replaced Colt’s hammer-mounted firing pin with a frame-mounted firing pin that was more robust, and less prone to breakage.

The Single-Six’s investment-cast, chrome-molybdenum frame was mated to an anodized, Alcoa aluminum grip frame and trigger guard. The use of investment casting and aluminum helped to reduce manufacturing and material costs, which allowed Ruger to sell his nifty revolver for $57.50 at introduction—a price that was considerably less than the centerfire Colt and Great Western revolvers of the era.

The Single-Six’s design and features would change over the years, and a number of models and variants would be produced. By the time I obtained my sample, the gun had evolved into the “New Model” format, which added a transfer bar safety that made it safe to carry the gun with six rounds in the cylinder. The Colt-style, half-cock hammer position, and associated loading procedure, were eliminated, and all a shooter had to do was open the loading gate to free the cylinder for loading and unloading.

My Six was made from stainless steel (introduced to the Single-Six lineup in 1974), and was also a “Super” model, delivered with both a .22 LR cylinder, and a matching .22 WMR cylinder. The Super’s fully-adjustable rear sight and ramp front sight were significant upgrades over the original Six’s drift-only, dovetailed rear, and integral, rounded front blade.

Introducing The Wrangler

Ruger sold their Single-Six revolvers by the truckload for over half a century, but as the years went by, the gun’s price tag climbed as a result of manufacturing costs. At the beginning of the Six’s life, materials were expensive and skilled labor was relatively cheap, but by the late-2010s the cost of paying workers to polish, fit and assemble the Single-Six was the long pole in the tent, and it was hard to keep the price down. The Single-Six had slowly evolved from a highly-affordable gun for the masses, to more of a dedicated enthusiast’s gun, with a sticker price that turned away the bargain-conscious shoppers in the market.

Those shoppers were instead turning to companies like Heritage Manufacturing, whose Rough Rider series of entry-level, single action .22 revolvers were selling for a fraction of what a Single-Six cost. The Heritage guns, with roots in the Herbert Schmidt and Hawes guns of the previous century, were simply not as nice as the Ruger Single-Six, but you could buy them for a third (or less!) of the price, and they shot well enough to satisfy the price point shopper. When Taurus International purchased the Heritage brand in 2012, and started marketing them more aggressively, they really started taking a bite out of Ruger’s profits.1

Ruger needed to get those sales back, and the solution was a new design they branded the Wrangler.

The Wrangler, released in 2019, combined affordable materials with modern manufacturing methods to produce a revolver that shared the Single-Six’s heritage and handling qualities, but not its price tag.

There were several keys to the Wrangler’s economy. First, by restricting the gun’s caliber to .22 LR only (no .22 WMR chambering), Ruger was able to build the cylinder frame out of aluminum alloy, instead of the more expensive steel alloy used in the Six.2 That aluminum cylinder frame, as well as the zinc-alloy grip frame, would be finished with an inexpensive Cerakote coating, eliminating the need for costly polishing operations, as the Single-Six required.

Many of the Wrangler’s action parts were manufactured with MIM processes that delivered rugged parts, with better consistency than their cast counterparts, at a lower price. These MIM parts, like the hammer and trigger, didn’t require extensive secondary operations (polishing, checkering, etc.) or detailed fitting during assembly, saving substantial manufacturing costs.

The Wrangler also reduced costs by replacing the Single Six’s adjustable rear sight with a fixed sight system that requires no additional parts or installation, and using an unfluted cylinder that could be produced with less machining operations.

Lastly, the Wranglers were all built to the same spec. They all had 4.62” barrels (in a nod to the Canadian laws that predated the despotic ban on all new handgun sales, in 2022), and they all had the same grips, sights, and features. Henry Ford famously said that, “Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black,” but Ruger graciously added Silver and Burnt Bronze to the color palette. That’s as far as the choices went, though. You had your choice of three SKUs, and they were all the same, except for the paint job.3

Limiting SKUs may not sound like a big deal to the average guy, but it makes a huge difference for a manufacturer. They can skip costly shut downs of the assembly line to switch out tooling and fixtures for the next variant, if all the guns are made the same. The logistical complexities of cataloguing, storing, and transporting a huge variety of parts are eliminated too, if there’s only one basic SKU. Keeping things simple by limiting SKUs helped Ruger save a bundle on the Wrangler’s production, and those savings could be passed on to the consumer.

Grand Slam

I don’t think Ruger anticipated how popular the Wrangler would be.

For about a third of the Single-Six’s cost, and just a shade more than the Rough Rider’s price, a buyer could purchase a Ruger-quality revolver that would last forever. The gun was seen as such a good value, at a street price around $200, that there was simply nothing else in its class.

Handgunners who had little-to-no interest in single actions or .22s were compelled to buy one, just to try it out, because the product was so attractive, and the barrier to entry was so low. On the other end of the spectrum, dedicated Ruger fans started buying the whole trio in a set, just so they could mix and match colors, by swapping cylinders and grip frames around. Even when the Covid-inspired ammunition draught made .22s hard to find and expensive to buy, the Wrangler continued to sell like hotcakes.

The market was absolutely nuts for the Wrangler, and Ruger couldn’t build enough of them. Justin was very pleased with the sample he received and tested, which nearly turned him into a .22 LR fan. Shooting the Wrangler was a highlight of my SHOT Show 2020 experience and transported me back to those youthful days with my treasured Single-Six. I must admit I wasn’t wild about the looks of the bronze and silver versions, but the black gun was attractive to my eyes, and it shot great.

Yes, but . . .

The gun was a smash hit, but that didn’t mean the market was satisfied.

Gun buyers are a hard bunch to please. You give them a new product, and the first thing they’ll do, after telling you how much they love it, is start listing the things they want you to change, right?

“That’s awesome! When will you make it in a .45?”

“Cool! When will the compact model be available?”

“Nice! Will there be a flat dark earth Cerakote (or single stack, or optics-ready, or .45 GAP, or whatever . . . ) model soon?”

So, it didn’t take long, after the Wrangler made its debut, for the market to start submitting their requests. It seemed that everyone loved the Wrangler, but they also missed some of the features that were found on the more expensive Single-Six, like the adjustable sights and the interchangeable .22 WMR cylinder.

Ruger had eliminated those features to make the Wrangler affordable, but there was enough demand for them that Ruger was forced to consider whether or not they could add them, and still keep the resulting gun affordable.

Enter the Super Wrangler

As it turns out, they could.

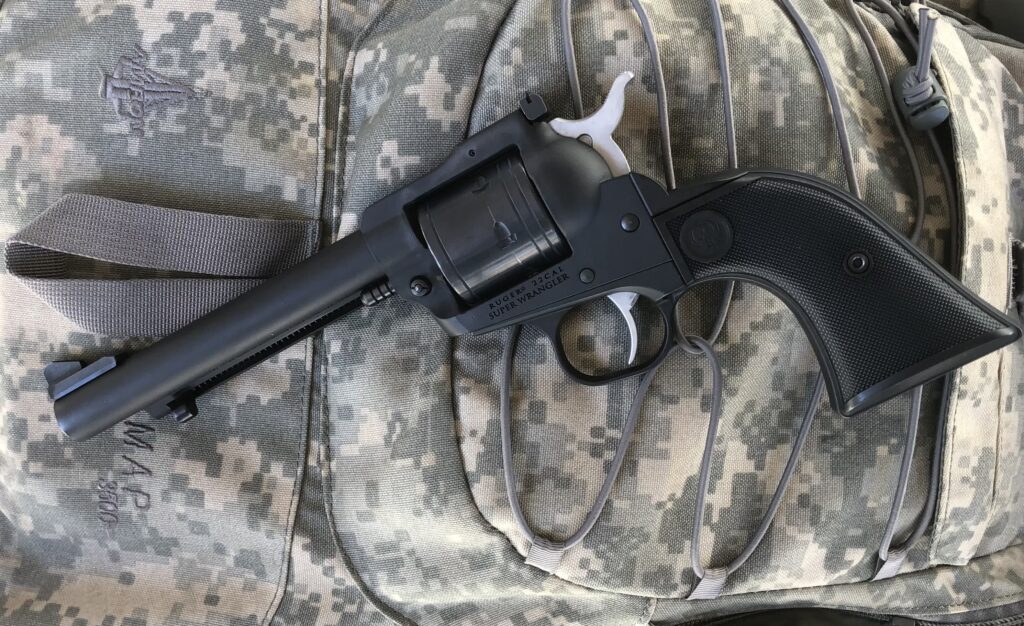

Following a naming convention established by the Super Single-Six in 1964, the new Super Wrangler features a thicker top strap than its predecessor, to house a fully-adjustable (windage and elevation) rear sight, and a ramp sight out on the end of the barrel. It also features an interchangeable cylinder in .22 WMR, for those who want more punch from the gun.4

To accommodate the .22 WMR chambering, the new Super Wrangler’s cylinder frame is made from alloy steel, to handle the increased energy generated by the littlest Magnum. This bumps the Super Wrangler’s curb weight to 37.7 ounces, up from 30.0 ounces on the original, aluminum alloy-framed Wrangler.

A bit of this increased weight is attributable to the Super Wrangler’s 5.50” cold hammer-forged barrel, compared to the 4.62” barrel of the original Wrangler. While I feel the 4.62” barrel was a good standard for the .22 LR Wrangler, I also think Ruger made an excellent choice by putting the longer barrel on the Super Wrangler, with its adjustable sights and .22 WMR chambering.

Aside from the cylinder frame material, the better sights, and the extra .22 WMR cylinder, the Super Wrangler follows the now-familiar pattern established by the Wrangler. The chrome-moly steel cylinders are left unfluted, the grips are checkered plastic (excuse me, synthetic), and the finishes are the same three flavors of Cerakote. The internals are largely MIM, including major assemblies like the hammer and trigger, and the grip frame is zinc alloy.

Following the Wrangler formula, which includes offering only three SKUs at launch, keeps the Super Wrangler affordable. The Super Wrangler’s extra features will set you back another $60 on the MSRP ($329, as of this writing), compared to the Wrangler, but will save you $470 compared to a blued, Single-Six Convertible of the same barrel length.

Yeah, that’s a bargain.

patiently waiting

I had expected to see the Super Wrangler make its grand appearance at the 2023 SHOT Show, but Ruger wasn’t ready yet, and we had to wait until April, and the NRA Annual Meeting, for it to arrive.

I made arrangements to have one shipped for test and evaluation as soon as it was announced, but because I had a few other projects already in the works, and because my state has a ridiculous “one in thirty days” restriction for new handgun sales (grrr!!), my testing of the Super Wrangler didn’t start until mid-June. I shot the Super Wrangler a little bit in July, but it wasn’t until August that I really started putting it through its paces.

Comparisons

Unboxing the Super Wrangler was fun, and took me back. After a quick glance to appreciate how the matte black finish was accented by the unfinished, silver-colored hammer and trigger, I went looking for the spare .22 WMR cylinder. My late ‘70s-era Single-Six had its spare .22 WMR cylinder in a cardboard box, that was hiding under a panel inside the gun’s box, but the Super Wrangler’s cylinder was found in a plastic bag. I looked to see if the Super Wrangler’s .22 WMR cylinder had the last three numbers of the gun’s serial number electro-penciled into it, like on my earlier Single-Six, but it did not. I’m going to speculate that Ruger’s modern manufacturing methods, using digital design and CNC machinery, have eliminated the need to hand-fit the Super Wrangler’s spare cylinder to the gun, like they used to on the Single-Six. This undoubtedly saves additional time and expense in the manufacture of the new gun.

When you look under the hood, you’ll discover the action on the Super Wrangler (and its Wrangler sibling) follows the New Model Single Six pattern, and differs from the Old Model Single Six’s in several regards. The Super Wrangler’s loading gate is powered by a shaped flat spring, instead of by a coil spring and plunger, as in the Old Six. The coil spring and plunger that powered the Old Six’s trigger are also gone, replaced by a simple wire torsion spring, whose legs straddle either side of the coil mainspring in the grip frame.

In a bit of a reversal, the cylinder stop is now powered by a coil spring and plunger that rests in a detent in the grip frame, instead of by a torsion spring, as on the Old Six. There’s also a flat steel guide for the hand that I don’t recall on the Old Six.

All of these features have been proven on the New Model Single Six over the course of many decades, so it makes sense for the Wranglers to follow the same pattern. The Wranglers’ MIM parts make the actions less costly to produce, but aside from that, they’re the same reliable action we’ve come to appreciate on the New Model Single Sixes.

The matte Cerakote finish on the Super Wrangler is less attractive than the polished steel of the Six-series guns, but that’s just where the market is, these days. In the Six’s prime, the most commonly encountered handguns were finely-polished blue revolvers with walnut grips, but today’s shooters are more likely to be shooting plastic-framed autos with matte black finishes. Thus, the Super Wrangler fits the contemporary market well, and most buyers won’t bat an eye at the Cerakoting. As a cosmetic plus, the Super Wrangler’s markings are much more tasteful than those on my 70s-era Six, which “has the entire manual written on the barrel.”

Handling

The first time I picked up the Super Wrangler, I was immediately impressed by its weight and balance. Having just handled a feathery, 4.62” Wrangler sample a few days prior, I was struck by the relative heft of the Super Wrangler, which “felt like a real gun” to me. The difference was only a little bit under eight ounces, but the gun had a more substantial feel than the Wrangler, which had always felt more like the cap guns I played with as a kid, than the Single-Six that I grew up shooting.

The 5.5” barrel on the Super Wrangler felt like it hit the sweet spot, giving the gun an excellent balance. I actually preferred it to the feel of the 6.5” barrel on my Single-Six, which I’ve always enjoyed. The 5.5” barrel on the Super Wrangler will do a good job of extracting the best performance possible from the .22 LR and WMR cartridges, while still being nimble. It will also provide a nice sight radius for those adjustable sights, which look to be the same unit found on the more expensive Single-Six.

Speaking of sights, that front ramp is nice and wide, compared to the Wrangler’s thinner blade, which makes it friendlier for these aging eyes. I’ll probably paint mine orange at some point, like I do with all of them, to improve the contrast with the black rear. I did struggle a bit to see that black front sight when I was shooting black bullseyes at 25 yards, so a little color up there will be helpful.

Opening the loading gate to verify the gun was unloaded brought up a point of comparison with my 70s-era Single-Six. The Super Wrangler, like the Wrangler before it, incorporates a free-spin pawl, which allows the cylinder to rotate freely in both the clockwise and counter-clockwise directions. This makes it easy to line up the chamber with the loading gate and ejection rod.

My old Single-Six won’t permit you to roll the cylinder counter-clockwise past a chamber, but the Wrangler and Super Wrangler will. This can be convenient if you accidentally skip a chamber during loading or unloading and want to go back to it. It’s also convenient if you don’t seat a cartridge fully into the chamber (perhaps due to fouling) and the case head gets hung up on the frame, as you turn the cylinder clockwise, stopping all cylinder rotation. In that event, you can just spin the cylinder backwards, and push on the cartridge to fully seat it. That wasn’t always possible under the old system, which didn’t like you turning the cylinder backwards.

Get a grip!

The checkered synthetic grips on the Super Wrangler are perfect for the task, I think. To my eyes, they look just like the old Colt SAA hard rubber grips, except they feature a Ruger raven crest instead of a Colt pony crest. These grips are a good cosmetic match for the Cerakote finish and are inexpensive to produce, which helps to keep the cost of the Super Wrangler under control. Fitting a pair of walnuts to this gun, as Ruger does on the Single-Six, would definitely hike up the price.

The checkered grips feel good in the hand, and anchor the gun in place without being too abrasive. Even though a .22 Magnum isn’t going to recoil a whole bunch, the checkering does a good job of keeping things under control while being comfortable. For those who may be wondering, the Super Wrangler’s grip frame dimensions are the same as the Wrangler’s, (old) Vaquero’s, Single-Six’s, and Blackhawk’s, so any of the XR3-RED-sized grips will work on the Super Wrangler, if you want to dress yours up with something different.

Action!

The action on my old Single-Six is smooth from many decades’ worth of shooting, so it’s not a fair benchmark to compare the new Super Wrangler to.

The best way I can describe this brand-new Super Wrangler’s action is to say that I think it’s quite good for an economy gun that’s assembled from a parts bin, without any real fitting. Cocking the hammer is “smooth” in that there’s no big hiccups or speed bumps to interrupt the movement, but my sample had a slight “crunchiness” to it, as I eared back the hammer. I could almost hear the crunch more than I could feel it, actually–it’s not like the hammer stuttered under my thumb, it stuttered more in my ears. There’s a definite “tink” as the transfer bar pops up into position at the end of the cocking.

Unsurprisingly, the hammer actually started to smooth out as I continued to shoot the gun. Nobody will use any phrases involving “glass” or “baby’s bottoms” to describe it, but it wasn’t a distraction to shooting, nor was it a labor to operate. Frankly, most folks won’t pay any attention to it.

I’ve read other reports where Super Wrangler samples had trigger pulls ranging from just under three pounds, to just over four pounds. The trigger pull on mine weighs about four pounds, eight ounces, according to a mechanical trigger pull gauge I borrowed from my buddy, and is actually pretty crisp. I was quite pleased with the quality of the pull, which I think can be attributed to good tolerances and surfaces on the MIM action parts.

A gun snob might criticize the Super Wrangler’s action, but I don’t think the average guy will think twice about it. It didn’t cause me any difficulty or concern when I was shooting, and I think it’s actually a pretty good action, from the box—a very good action, considering what the gun sells for. In any event, it’s already smoothing out and I have a suspicion that will continue to improve as I put some mileage on the gun, just as my Single Six did.

First rounds downrange

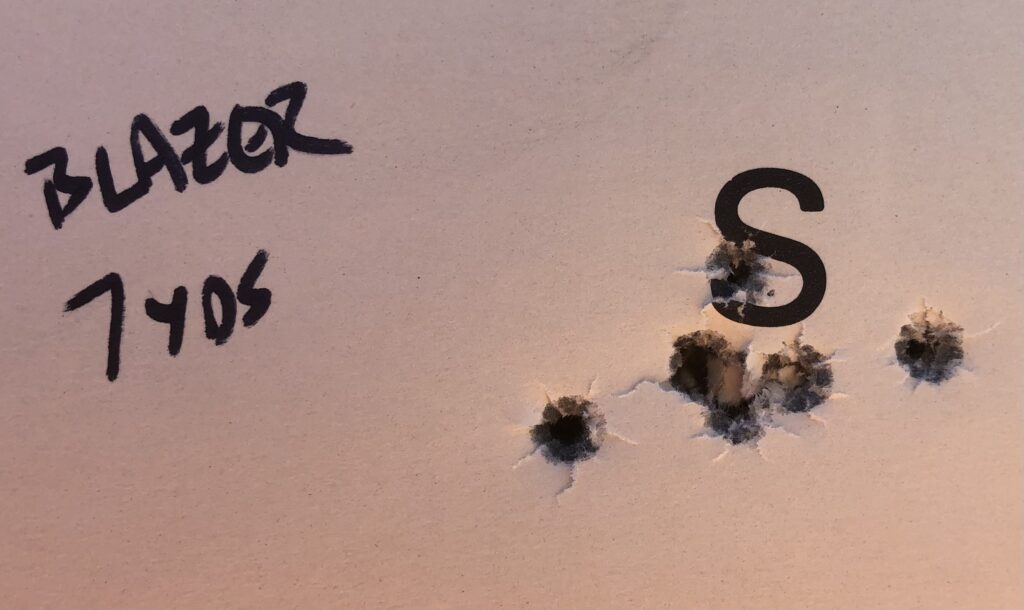

My first rounds from the Super Wrangler produced a gratifying group that hit exactly to the desired elevation at a distance of 7 yards. I can’t begin to tell you how excited I was to see that the sights had been properly regulated before they left the factory, because that has NOT been the case for most of the new guns I’ve shot in the last couple years. BRAVO, Ruger!

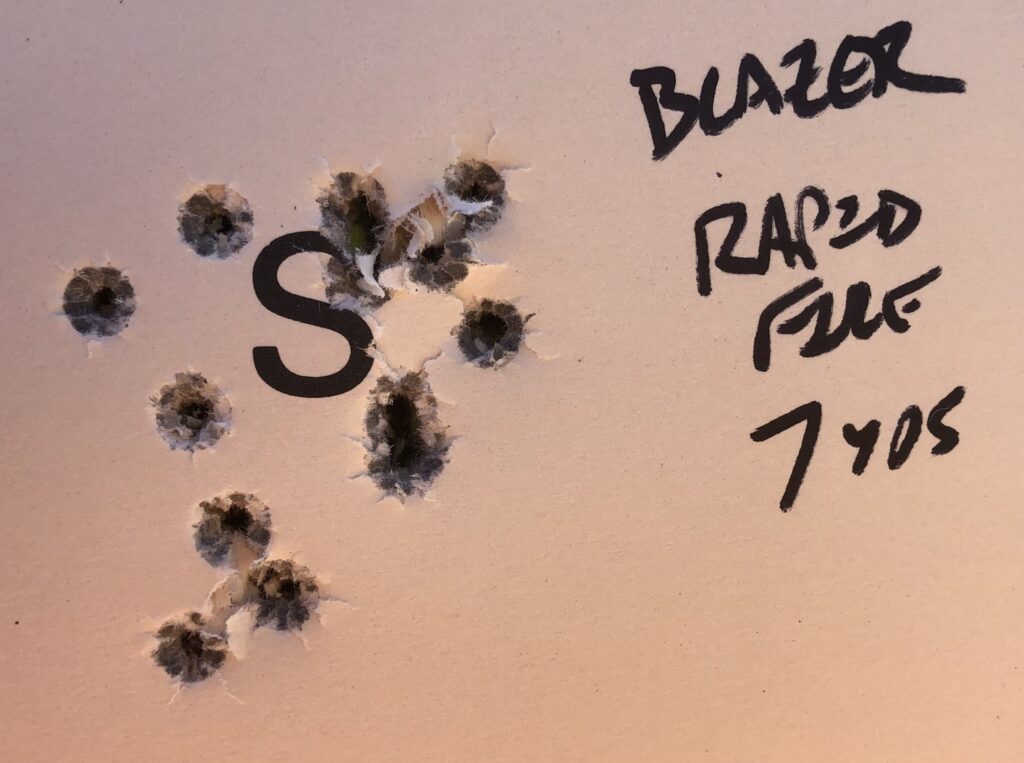

I shot about 50 rounds of .22 LR through the Super Wrangler, just to get the feel of it, before I settled into shooting groups for record, at distance. At 7 yards I was able to keep 40 grain, CCI Blazer in a tight little cluster when I took my time, and a 1.5” x 1.5” (outer diameter) group when I worked the hammer and trigger as fast as I could.

It was clear to me that the shooter was going to be the weak link, not the gun!

After some goofing around at 15 yards, I decided to get working on the bullseyes at 25 yards, from a few sandbags on the bench. I didn’t get far before I came to the conclusion that I just didn’t have it in me, that day, to be doing accuracy testing. I’d been on the range all day at this point, and was already pretty tired, and I didn’t feel like I was giving the Super Wrangler a fair shake. I was shooting 4” groups with the 40 Grain Blazer and 40 Grain Winchester Wildcat at 25 yards, struggling with the black sights on the black bullseye. I did manage to shoot a pretty nice 2” group with the Winchester Wildcat, which I felt was more representative of the gun’s capabilities, but after getting frustrated with myself, I decided to try again, on another day.

Take Two

Things went better on a subsequent trip with the Super Wrangler, and I felt like I was giving the gun a better chance to show what it was made of.

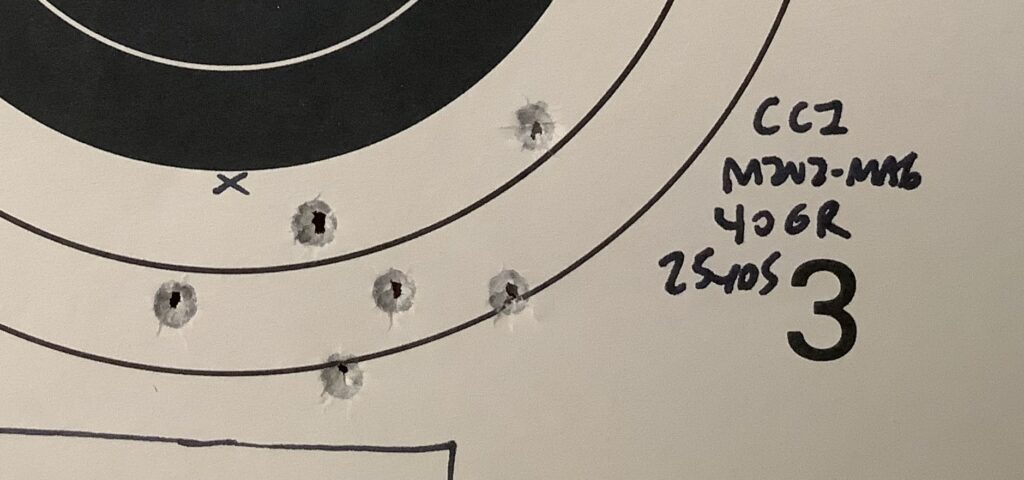

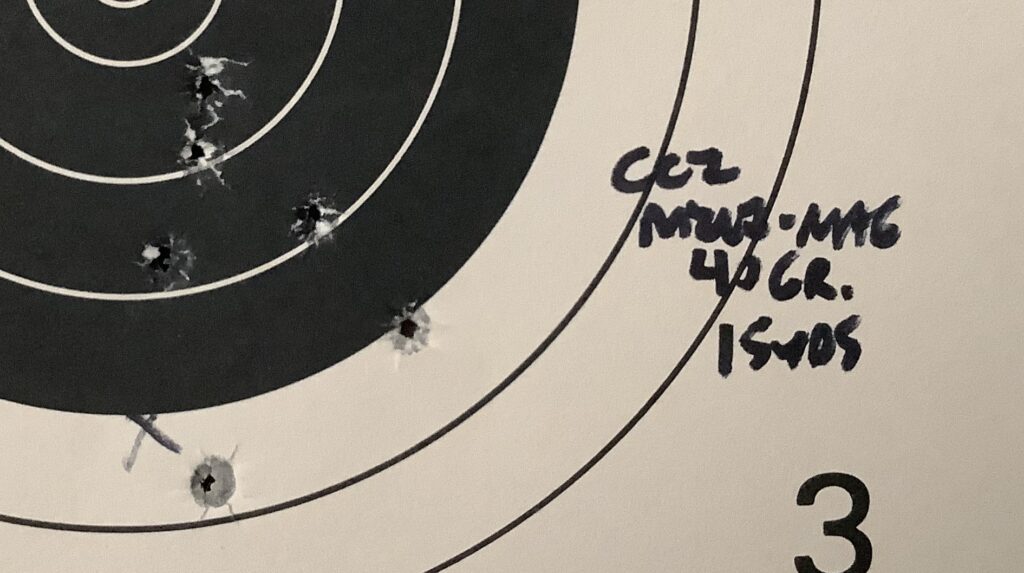

I brought along a mix of .22 LR ammunition to run through the Super Wrangler, along with the single brand of .22 WMR that I had in my supply, and proceeded to bang away at 25 and 15 yards from an impromptu rest on top of my day pack. The Long Rifle loads included Winchester Wildcat 40 Grain LRN, Aguila Sniper Sub-Sonic 60 Grain LRN, CCI Stinger 32 Grain copper HP, CCI Target Mini-Mag 40 Grain copper RN, and Federal Champion 36 Grain copper HP. The sole .22 WMR load was CCI Maxi-Mag 40 Grain copper JHP. I fired six-shot groups for all the Long Rifle loads, and 5-shot groups for the single Magnum load, shooting a pair of 15 yard groups and a single 25 yard group for each.

Although it seemed that a slight windage elevation would have been helpful, I left the sights alone for consistency across all the brands and loads of ammunition, instead of changing them midstream. I trended a little right on most of my groups, which could easily be the result of putting too much trigger finger in the guard (using the crease, where I get that leverage for working DA triggers, instead of the fingertip), or just wrapping big hands around a small grip. I also didn’t fiddle with elevation adjustments, so I could compare the relative point of impact for all loads with a consistent point of aim at Six O’Clock on the bullseye. One of the key selling points of the Super Wrangler is the adjustable rear sight, of course, but I left it alone for this comparison.

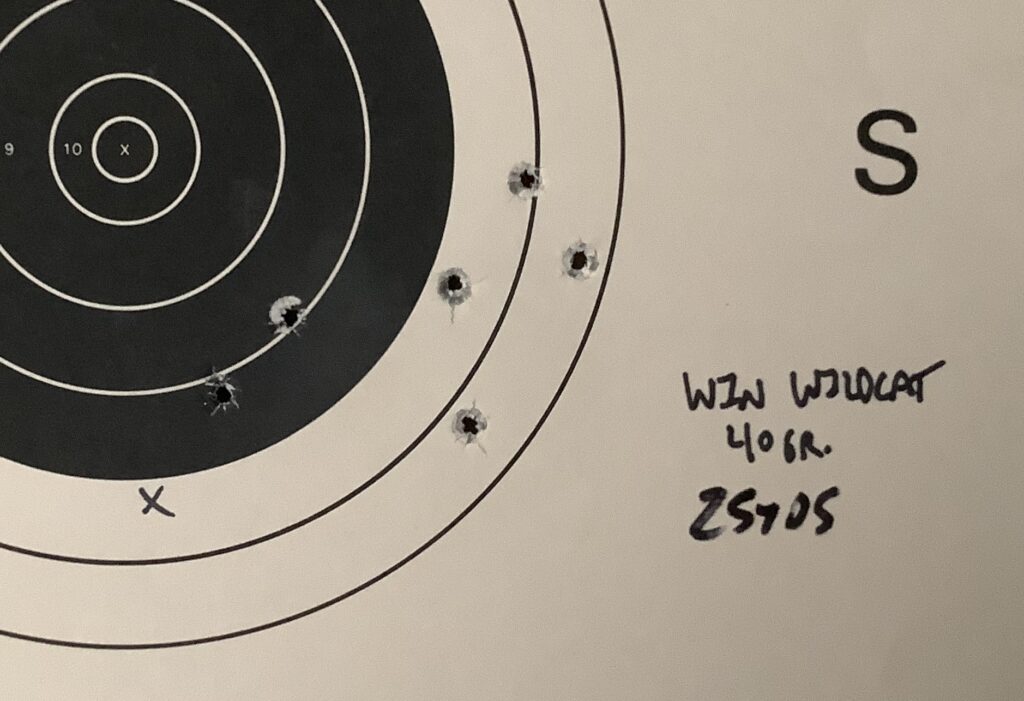

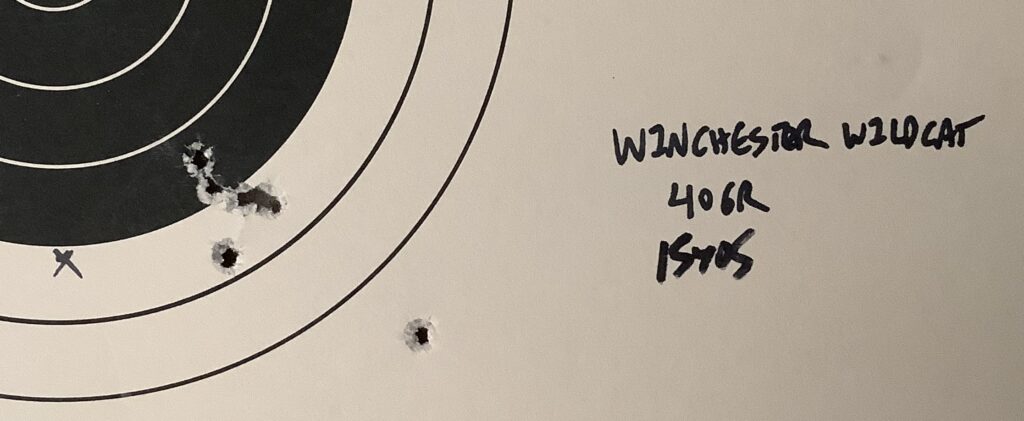

At 25 yards, Winchester Wildcat gave me a nice group that measured 1.5” high x 2.25” wide (measured from outside edge to outside edge, or outer diameter–O.D.), centered 1” above the point of aim, which I was able to reduce to reduce by about half at 15 yards, with the best group measuring 0.875” high x 0.50” wide, excluding one pesky flyer.

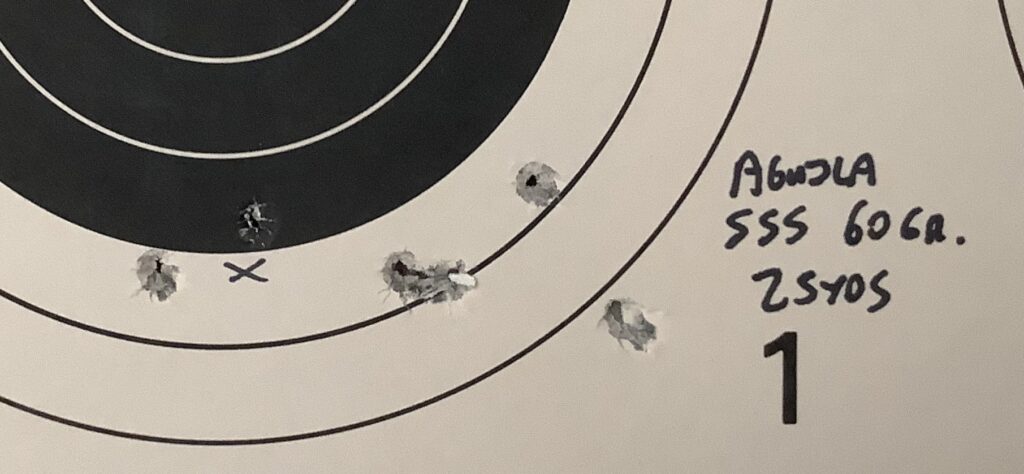

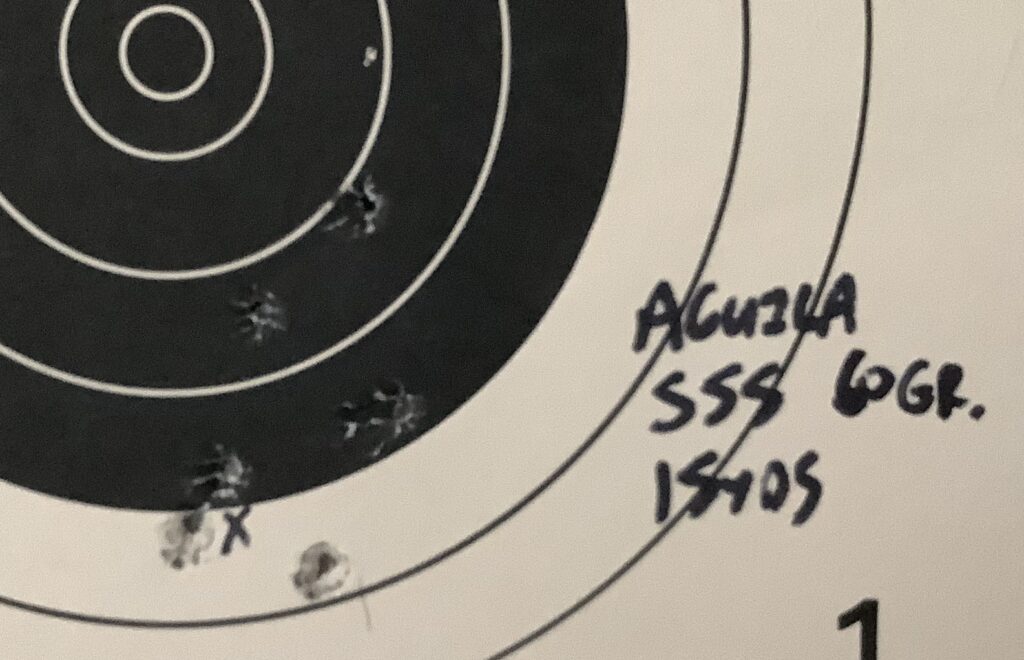

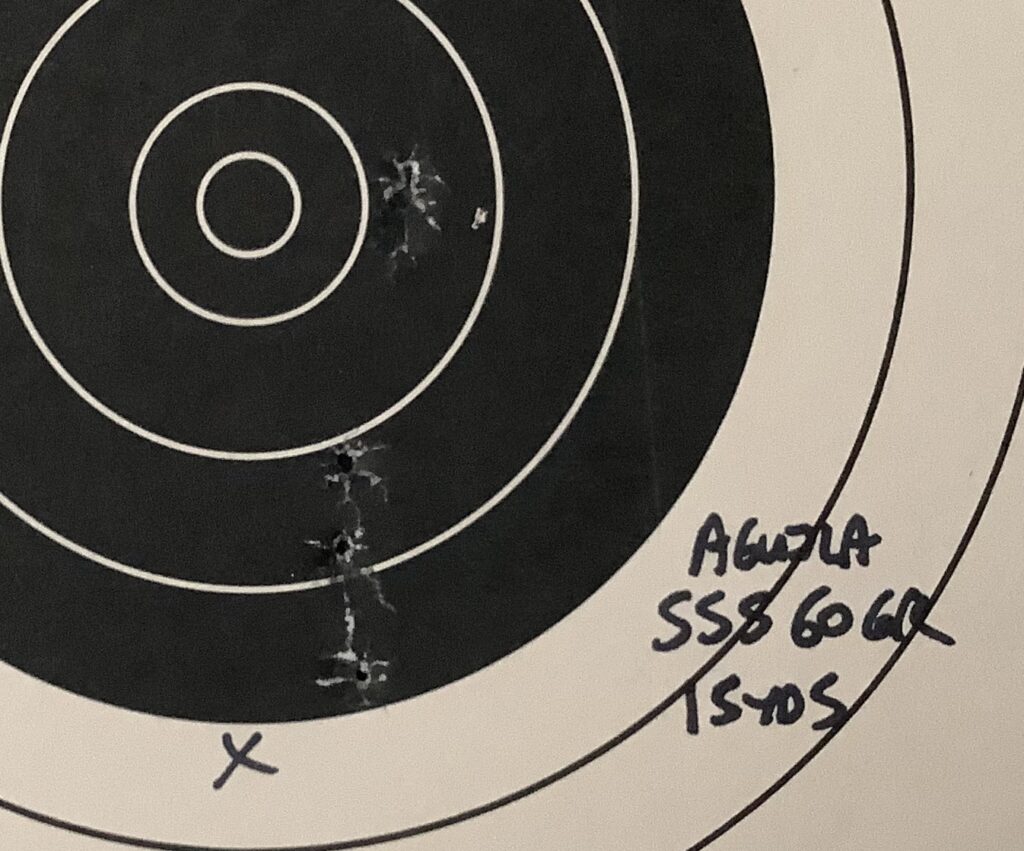

At 25 yards, the heavy and slow Aguila load printed a 0.875” high x 2.25” wide (OD) group that was centered for elevation even if I wandered a bit in azimuth, and at 15 yards I shot a couple vertically-stringed groups with the load, including a 1.625” high x 1” wide (OD) group that put 4/6 in a 0.875” high x 1” wide cluster at the proper elevation.

At 25 yards, the heavy and slow Aguila load printed a 0.875” high x 2.25” wide (OD) group that was centered for elevation even if I wandered a bit in azimuth, and at 15 yards I shot a couple vertically-stringed groups with the load, including a 1.625” high x 1” wide (OD) group that put 4/6 in a 0.875” high x 1” wide cluster at the proper elevation.

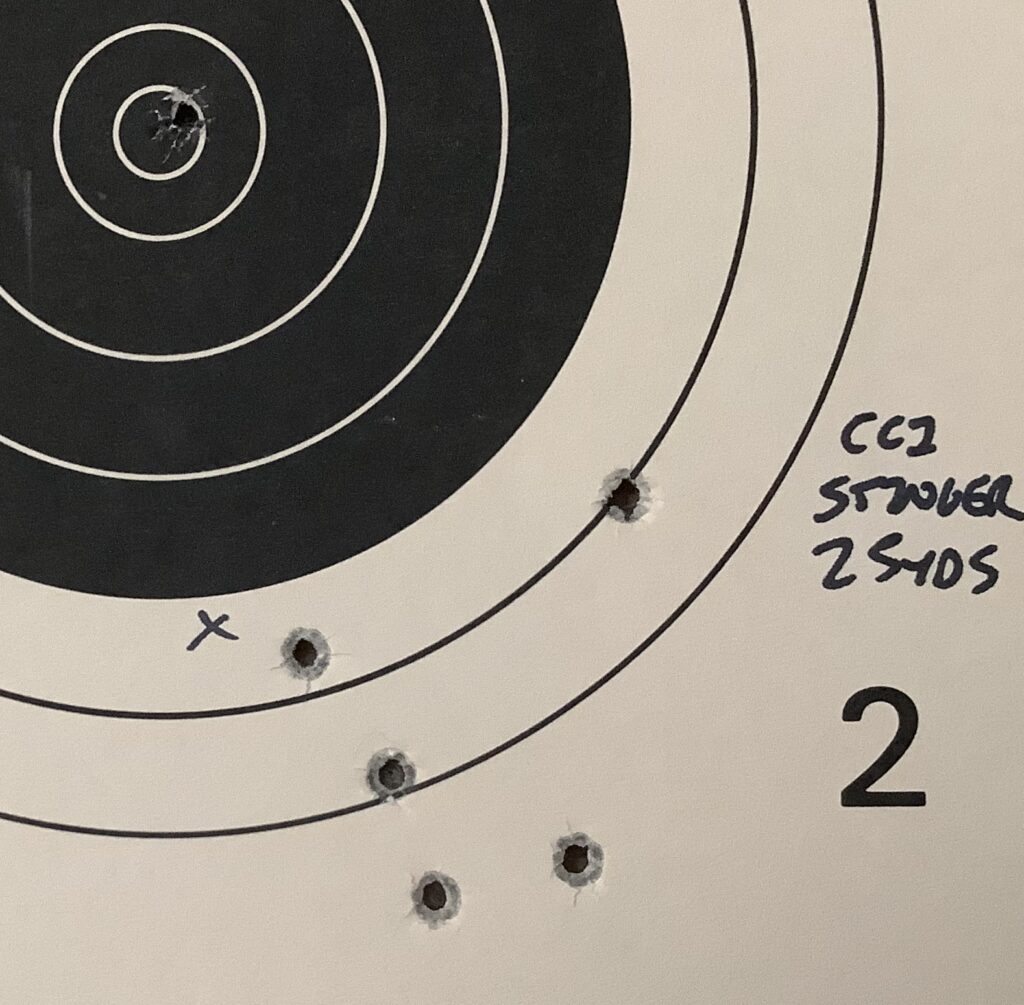

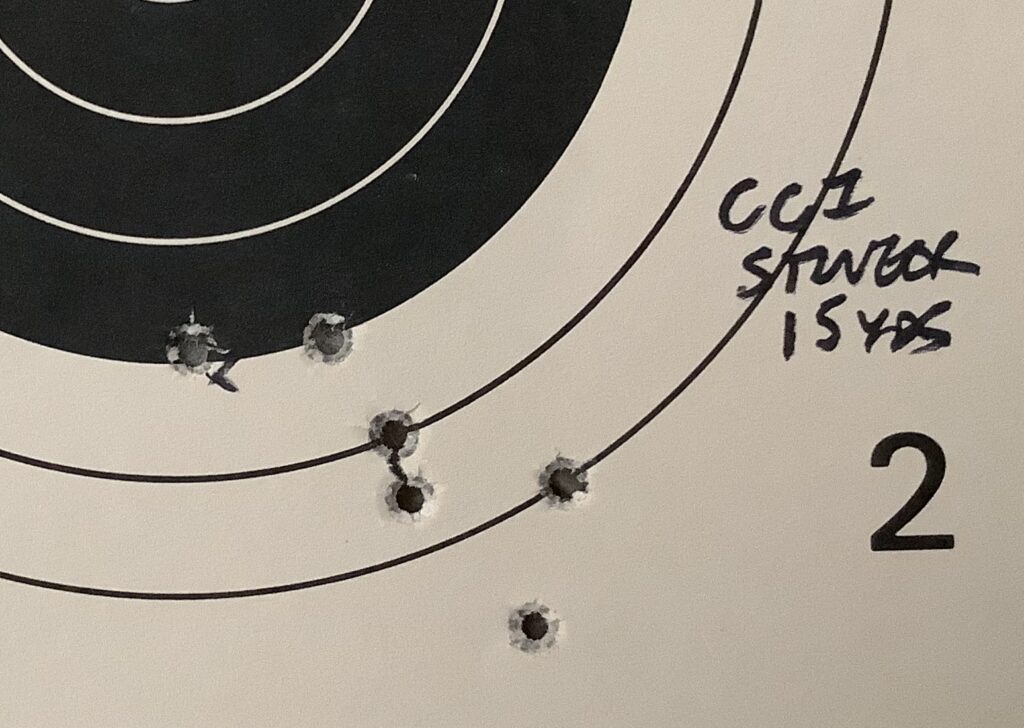

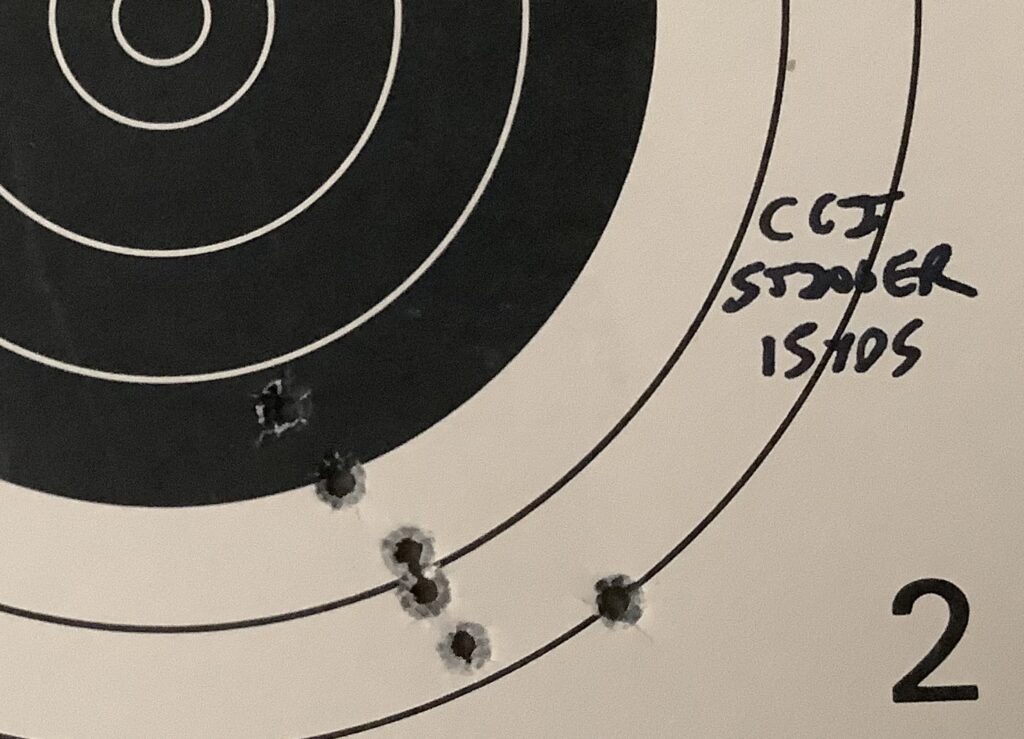

At 25 yards, I threw one of the zippy CCI Stingers high, but put the remaining 5 in a 1.825” high x 1.5” wide (OD) group. I did better at 15 yards, with a couple groups in the 1.25” high x 1.5” wide (OD) range, centered about 0.5” below the point of aim.

At 25 yards, I threw one of the zippy CCI Stingers high, but put the remaining 5 in a 1.825” high x 1.5” wide (OD) group. I did better at 15 yards, with a couple groups in the 1.25” high x 1.5” wide (OD) range, centered about 0.5” below the point of aim.

The CCI Mini-Mag produced a 1.375” high x 2” wide (OD) group at 25 yards centered about 0.5” low, and at 15 yards I shot a nice group that measured 0.825” high x 0.625” wide (OD) which was one of my nicest efforts of the day.

The CCI Mini-Mag produced a 1.375” high x 2” wide (OD) group at 25 yards centered about 0.5” low, and at 15 yards I shot a nice group that measured 0.825” high x 0.625” wide (OD) which was one of my nicest efforts of the day.

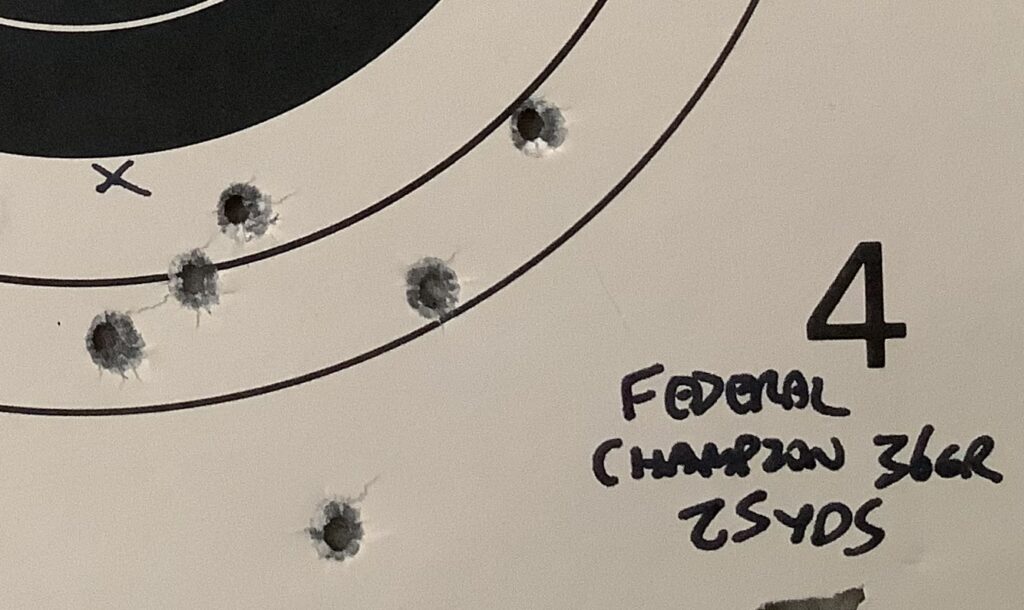

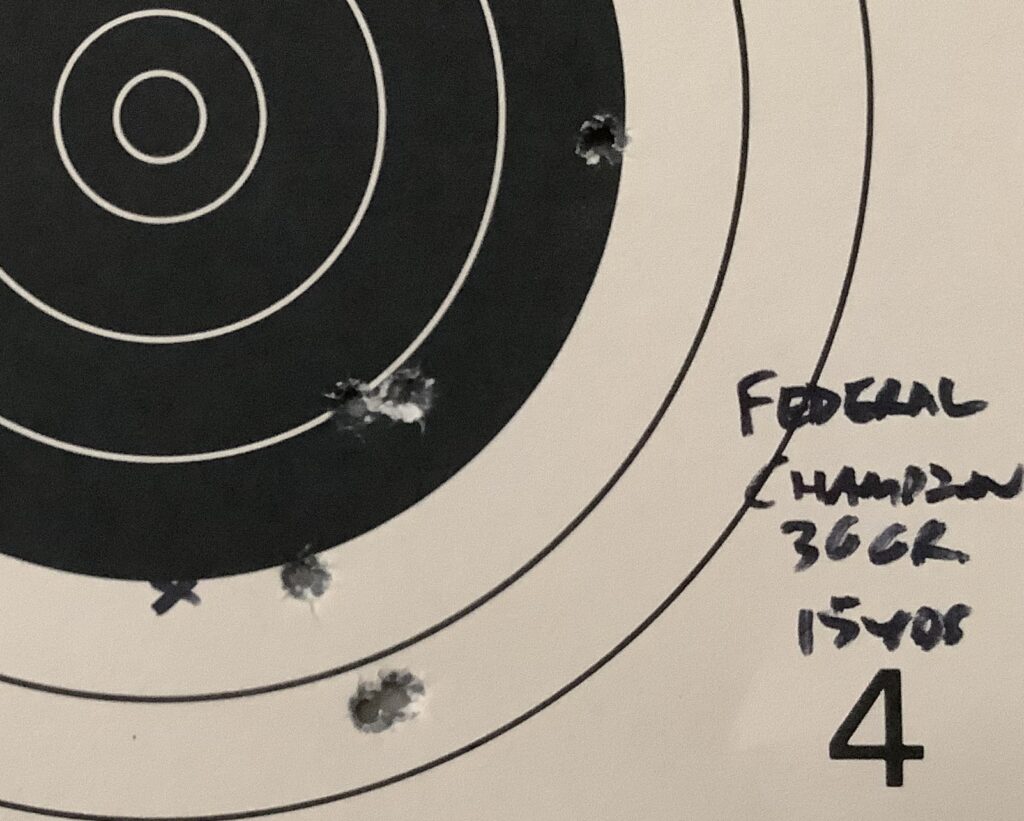

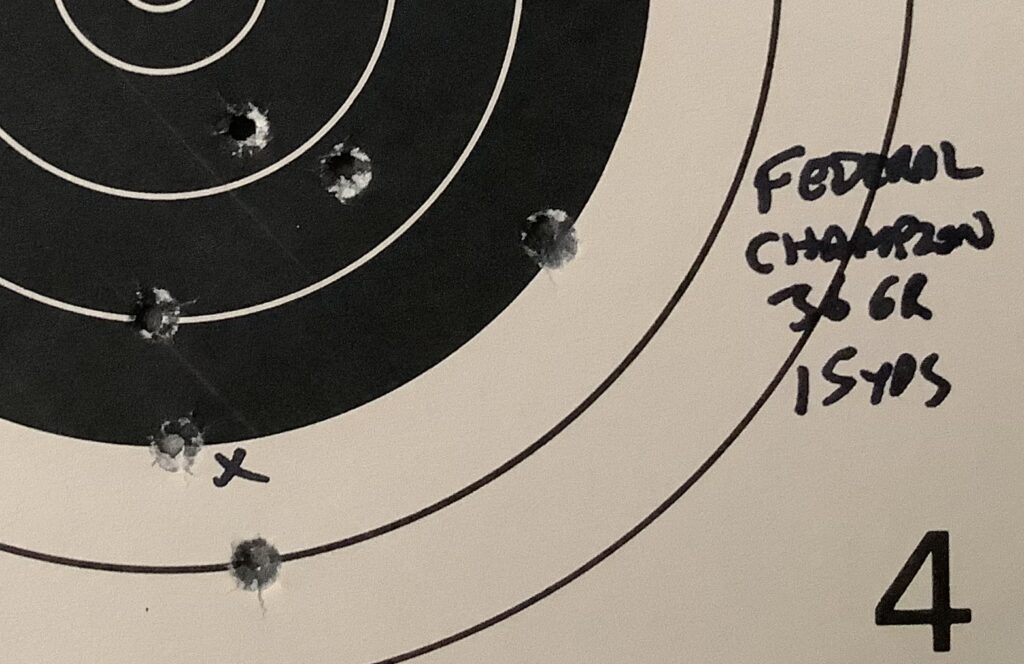

The Federal Champion economy load shot a 1.75” x 1.75” (OD) group at 25 yards that wasn’t much different at 15 yards, probably because I was getting fatigued. A second group at 15 yards rewarded me with 5/6 in a 1.5” high x 0.625” wide group.

The Federal Champion economy load shot a 1.75” x 1.75” (OD) group at 25 yards that wasn’t much different at 15 yards, probably because I was getting fatigued. A second group at 15 yards rewarded me with 5/6 in a 1.5” high x 0.625” wide group.

Magnum Force

Pushing the transverse cylinder pin lock and pulling the pin out the front of the frame allowed me to remove the dirty .22 LR cylinder (which doesn’t have a caliber marking) and quickly replace it with the .22 Magnum cylinder (marked “22 Win Mag”). In just a minute, I made the switch and was ready to start shooting groups with the Magnum rimfire.

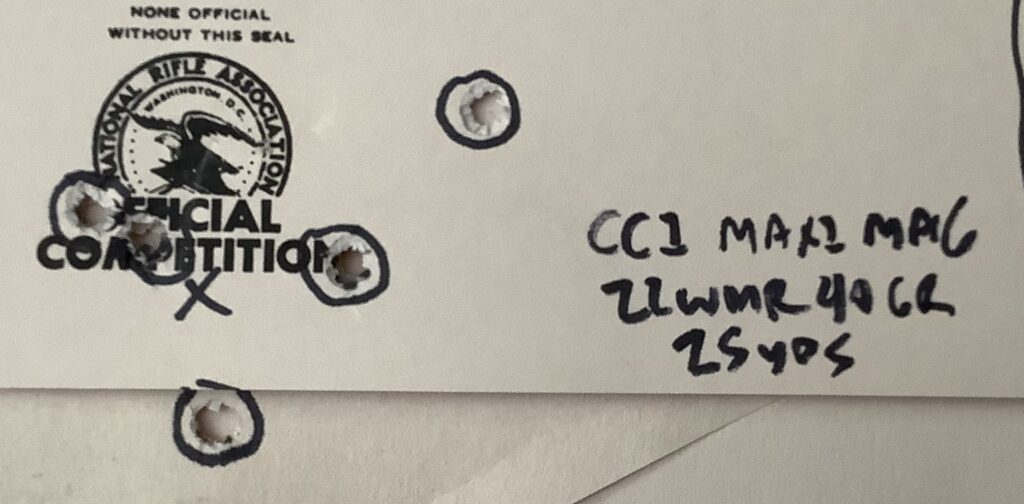

Although I didn’t have a wide variety or quantity of Magnum loads to shoot, the handful of CCI Maxi-Mags I shot put in a performance that raised my eyebrows. At 25 yards, shooting at the tiny NRA seal in the bottom corner of the target, I shot a 5-round group that measured 1.75” high x 2” wide (OD), which shrank down to 1.25” x 1.25” when I threw out the worst of the shots. This was an amazing performance from the Magnum load on a target that was much harder to see than the larger bullseye, which made me question whether or not I was simply focusing more on the right things as a result of the challenge, or if the Magnum load was just more consistent than the Long Rifle loads?

I’d read other reviews where shooters experienced better accuracy with the Magnum cylinder in place on their samples, and I suspect this is a function of a better bullet-to-bore fit. The Super Wrangler barrel is bored for the slightly larger WMR load, and the smaller Long Rifle loads don’t grip the lands and grooves as well. The Long Rifle bullets will obturate and seal the bore, but they don’t seem to fly with the same accuracy as the Magnum loads in these convertible guns.

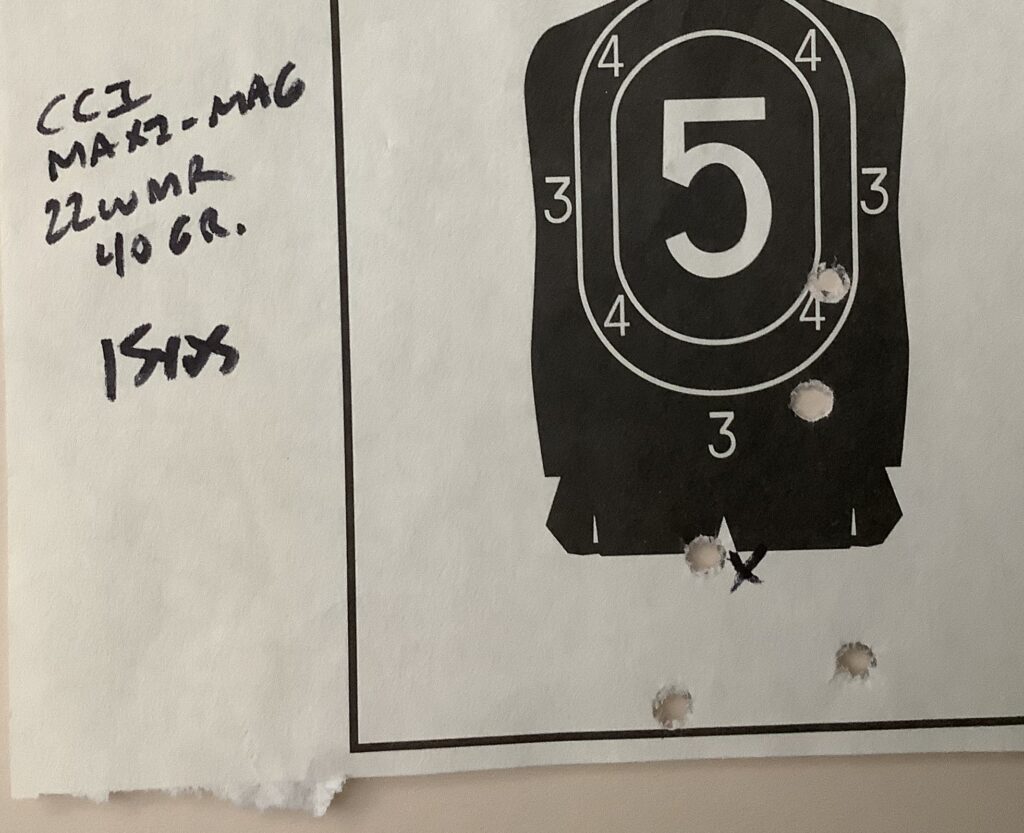

At 15 yards, I fired my last group of the day with the Maxi-Mag at the reduced-size, scoring key for a silhouette target that was stapled underneath my bullseye targets, and had a less impressive result than I had at 25 yards, but I think the group still demonstrated the WMR’s inherent accuracy. The 5-shot group had some vertical stringing, but still put the best three in a group that was only 0.825” high x 1.25” wide (OD), about 0.5” low with the factory sight settings.

Aggregate

If my effort is any indicator, the Super Wrangler is roughly a 1.0” – 1.5” gun at 15 yards, and a 1.5” – 2” gun at 25 yards with a variety of .22 Long Rifle loads, and a 1.0” – 1.25” gun at 15 and 25 yards with the Magnum cylinder in place. I think that’s plenty accurate for the kind of shooting that most RevolverGuys will do with this fun little gun. It’s certainly good enough for the plinking and small game hunting this gun will be called upon to do.

I have no doubt that a skilled shooter could extract even more performance from the gun, particularly with the Magnum cylinder in place, but with your average gun owner behind the trigger, the gun still delivers solid performance, on par with what you can expect from the much more expensive Single Six series.

A hiccup

After about 250 rounds downrange, I encountered my first speed bump with the Super Wrangler. The hammer froze and would not allow me to cock it. I suspected that some fouling had entered the action and jammed up the works because rimfire ammunition is inherently dirty, and I’ve experienced that problem with my Single Six in the past. However, when I disassembled the Super Wrangler at home to clean the guts out, I didn’t see any signs of fouling.

After a close inspection of the action, I realized that the cylinder stop trip plunger, which rides in a channel in the base of the hammer, was getting stuck up inside the hammer, and wouldn’t rebound. I suspected this was interfering with the proper operation of the cylinder stop and preventing me from cocking the gun. I removed the spring and plunger, cleaned them off, and inspected them. I didn’t see any rough edges on the plunger, so I flushed the hammer channel the plunger rested in, lubricated the plunger and spring, and reassembled the gun. It worked well for about a dozen dry-fires, but seized up again, and wouldn’t allow me to cock the hammer.

Rats.

For a moment, I considered disassembling the gun again, and checking the cylinder stop plunger channel for a rough spot or trapped debris, but I was a little nervous about making things worse (the last thing I needed was to damage the channel, or break off a tiny drill bit inside there!). Plus, I wasn’t sure if there was something else going on, so I figured it would be best to let Ruger have a look at it.

Great service

I called Ruger Customer Service and spoke to a friendly representative, who got me set up with a prepaid FedEx shipping label right away. She told me they would send a confirmation when FedEx delivered the gun, and to be patient, because it might take a few weeks before they could get to the job, since the factory was busy these days. To keep me informed, they would send email updates as necessary.

Happily, Ruger got the job done much faster than I expected. I shipped the gun off to them on the 22nd of August, and by the 6th of September it was already back in my hands. The repair paperwork indicated they had replaced the hammer (which seemed to confirm my diagnosis) and test fired the gun. As an apology for my troubles, they returned the gun with a nice silicone cloth that had the Ruger logo on it—a nice touch.

Back to the range

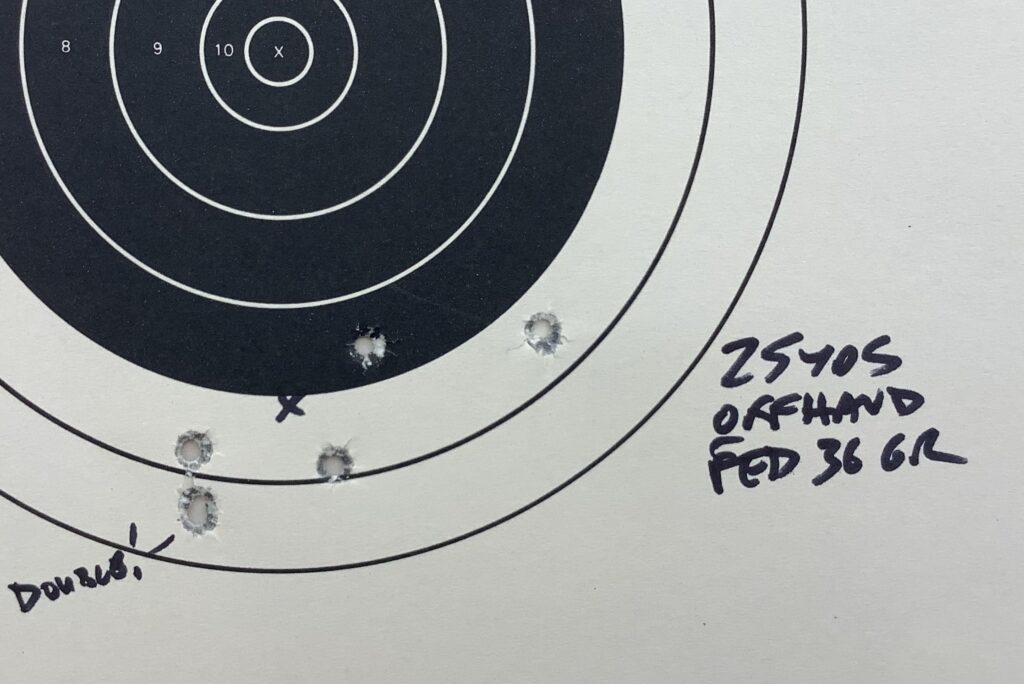

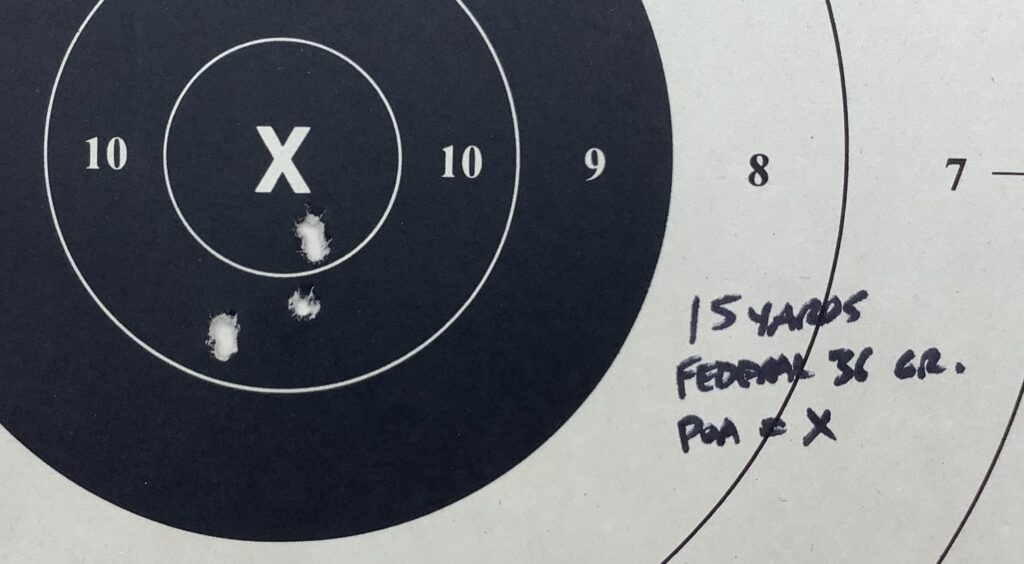

The new hammer was like the first one—a little “crunchy”–so I lubricated it with some CLP and went off to the range with some Federal Champion 36 grain cartridges. I started out with some offhand groups at 25 yards and was pleased to see that I was shooting tighter groups with the load than I had before, from the bench! The best of them measured 1.25” x 2.0” (O.D.) and was nicely centered for azimuth and elevation, hitting right to the point of aim at 6 O’Clock on the 3.75” black bullseye.

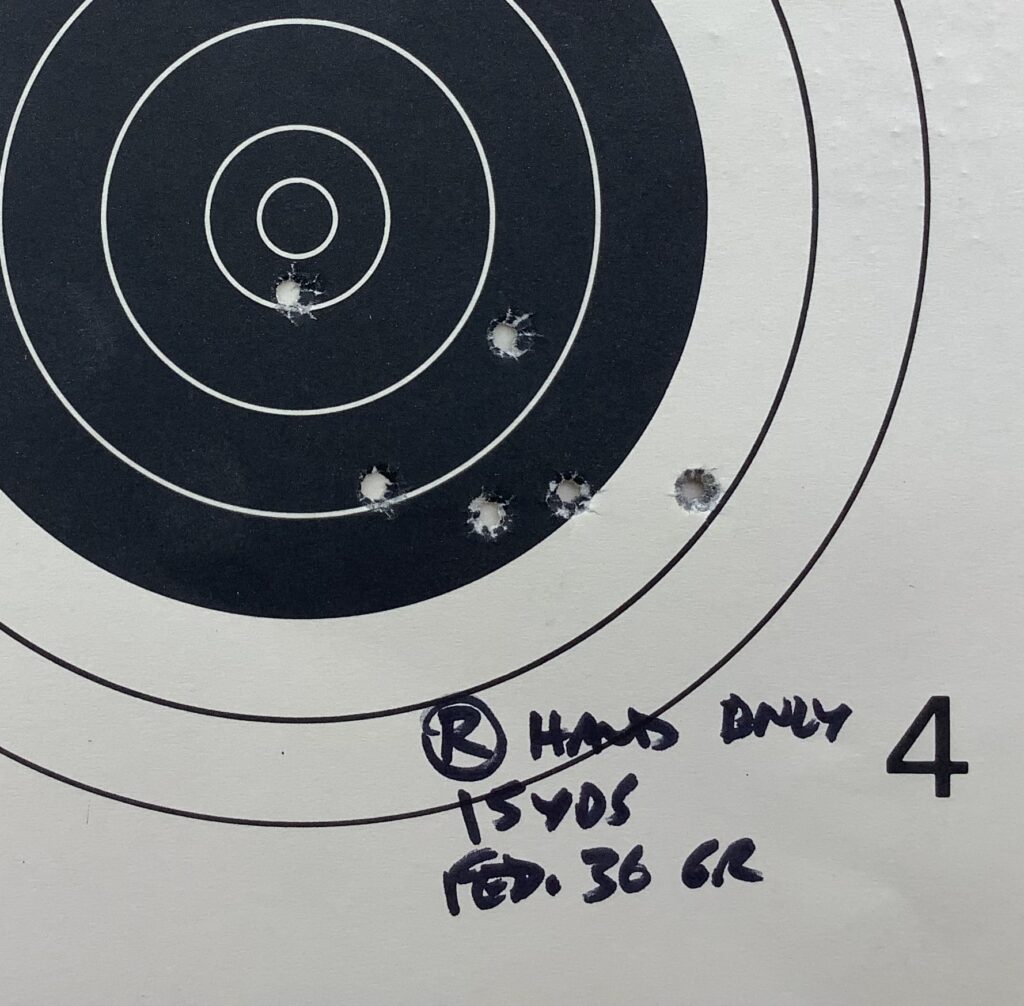

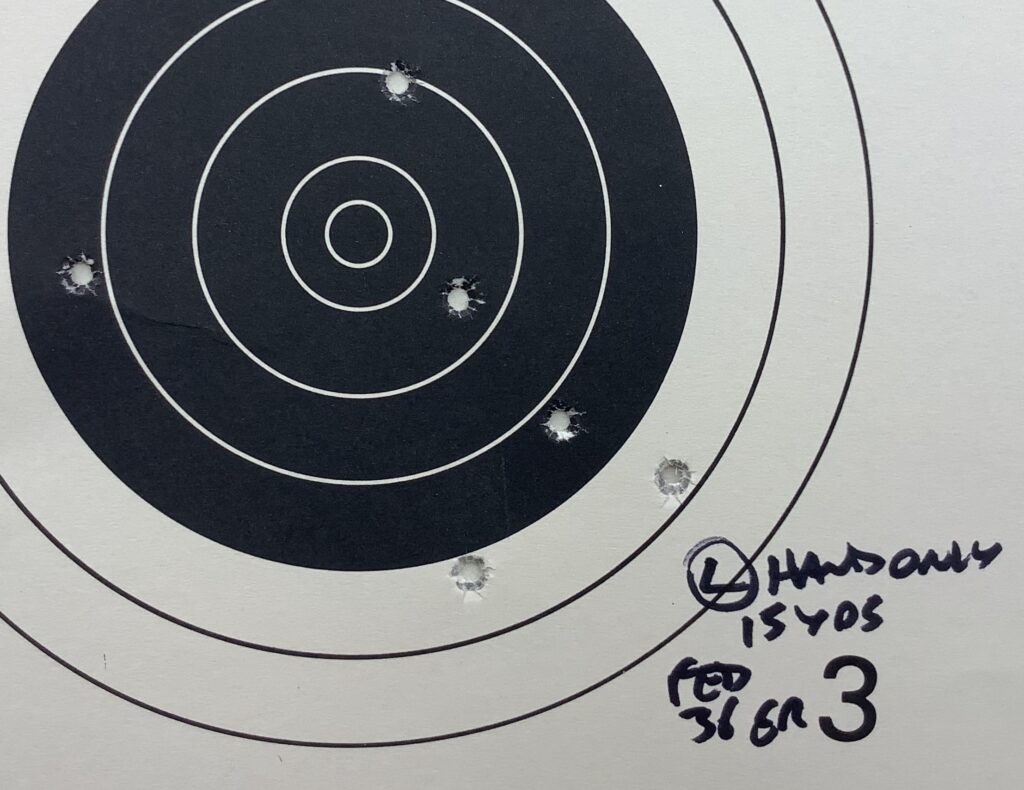

Right-hand-only and left-hand-only groups at 15 yards followed, and once again I was pleased with the performance of the gun, which ran 100 percent. I shot a 1.25” x 2.0” (O.D.) group with my right hand that was a little right of center, but looked good.

For grins, I fired a benched group at 15 yards which gave me a 1.0” x 0.75” (O.D.) cluster, just below my point of aim. I was happy to see that my groups were properly centered for windage that day—had the gun received a sight adjustment when it was back at Ruger, or was I just doing a better job shooting the gun? I suspect the latter.

That was enough “paperwork,” so I decided to have a little fun on some steel. I fired about 100 rounds at a 1/3 scale popper target located 25 yards downrange, and kept it ringing with both one and two-handed shooting grips, going five-for-six with some regularity, and even getting a few “possibles,” despite the fact that the popper was dirty gray and hard to pick out from the dirt backstop.

Next up was an 8” steel plate on the 100-yard rifle range, which required me to lift the front sight out of the rear notch a little bit, “Keith style,” to make hits. I drew a small crowd of riflemen who were amused by the effort and happy to call my shots. I fired about 30 rounds at the gong, bracketing it closely the whole time, and when I finally figured out the range, I got about 10 hits or so, to the crowd’s delight.

It was a great morning with the repaired Ruger, and by the time I was done shooting, the new hammer was noticeably smoother to cock. The gun functioned perfectly and I was pleased to see that I was shooting it better than I had during my first outings with it. I guess I was learning the gun.

Plans

I’m very fond of this new Ruger and look forward to working more with it. I was disappointed that it needed to be repaired, but Ruger made the whole process as painless as possible and got me back to shooting in no time. Their warranty service was great, and I can assure the RevolverGuy audience that they’ll take care of you in the rare event that a repair is necessary.

Up to this point, I’ve left the adjustable sights alone, but I’ll probably start fine-tuning them for a zero with my preferred loads, and will probably add some orange paint to the ramped front sight, so I can actually see it against dark backgrounds with my uncooperative, aging eyes. I’ll also think about a muzzle crown, per Roy Huntington’s advice, as he reports it’s working wonders to improve the accuracy of the Wranglers he’s modified, cutting group sizes almost by half.

I may also dress it up a little with some inexpensive grips from Arizona Custom Grips or Premium Gun Grips that would be just the right embellishment for this economy blaster. Honestly, the Super Wrangler’s performance is good enough to justify a more expensive set of customs from Chig’s Grips, and he has some very attractive blanks in stock that are calling my name . . .

Either way, this Super Wrangler will displace my Single Six for a while, and get all my single action attention. I’m really impressed with what Ruger was able to do on this gun, especially for $300, and look forward to slicking up the action the old-fashioned way—by shooting it!

I’m also looking forward to the product extensions that will invariably follow. I have no doubt that Ruger will add more Super Wrangler SKUs in the future, just as they did with the Wrangler. It will be exciting to see what they come up with, and we’ll report on it here, when they do.

*****

Endnotes

- I’ve seen a few of the earlier Herbert Schmidt guns and a much greater number of the Heritage guns, and while I’d rate the Heritage products as a step up from their forbears, they’re still pretty rough. They usually function OK (I’ve only seen one break, so far), but the fit and finish aren’t stellar, the actions aren’t great, and they’re just not as refined as the gun that Ruger built to compete with them. We had a sample at the club a while back that couldn’t stabilize its bullets, which were obviously tumbling when they smacked the paper. An inspection of the gun showed the timing was so bad that the bullets were getting damaged as they struck the side of the (extremely generous) forcing cone, after exiting the ball end of the cylinder. You do get what you pay for, when it comes to guns;

- The Wrangler is not the first Ruger single action to offer an aluminum frame. A Lightweight model of the Single-Six was produced in the mid-to-late 1950s that featured not only an aluminum frame, but also an aluminum cylinder (for a while—later changed to alloy steel). These guns featured 4-5/8” barrels, to save more weight;

- Since its introduction, the Wrangler line has expanded to also include barrel lengths of 3.75”, 6.50” and 7.50”, a Bird’s Head grip frame option, and a few extra color and grip choices on some distributor specials, but these minor changes can be easily accommodated without adding significant unit costs. At its core, the Wrangler remains the same gun, regardless of cosmetics, and this helps to keep the sticker price low, even as SKUs have multiplied;

- Can we just break for a moment, for me to say how appreciative I am that Ruger continued this naming tradition? While I’ve been frustrated with many companies for inappropriately recycling classic product names (Cobra, King Cobra, M&P . . . ), I was really tickled to see Ruger properly honor the historic “Super” label on this new product. Great job, guys!

About a year ago, friend of mine let me shoot his Ruger Wrangler, and though the handgun’s fit and finish were rather crude, it was surprising accurate for having just a non-adjustable, gutter rear sight. The Super Wrangler, with its adjustable rear sight, should be even more accurate, but I haven’t test-fired one. My stainless Single-Six Convertible is a tack driver in both chamberings, so it would be fun to compare it to the Super Wrangler, if I ever get the chance.

If a guy or gal doesn’t doesn’t have much loose cash lying around and just wants a plinker or woods gun, the Wrangler and Super Wrangler will do.

Spencer, you can see that my groups got better after the warranty return, and I think I was finally getting in the groove with the gun, and starting to demonstrate it’s true accuracy potential. It will definitely shoot better than I can.

I had planned to shoot my Single Six side-by-side with it for comparison, but ran out of time. I’ll probably do that as a separate piece and write it up sometime.

Very good write up. C’mon Mike, you know you’re a Single Action afficionado surrounded in a world of double action revolvers. ; )

My first handgun in the 1960s (and yes, I actually remember the 60’s) was a plain jane Single Six with a 6.5 inch barrel. It got shot and toted around so much most of the blue finish was faded away. A couple of years later, a .357 Blackhawk Convertible was added, and even in high school and later in undergrad, I managed to have time to cast enough bullets to make Elmer Keith and Mike Venturino proud.

Single Action Rugers are, IMNSHO, are the most reliable, most rugged handguns in existence, and the ‘New Model’ versions even moreso. In nearly 60 years of my Single Action life, I’ve never had problem one with any Ruger firearm! When society finally melts down, I want my Super Single Six and Blackhawk – and my GP100s – with me. I’ve looked at the Heritage and others single action clones, but they come in as an also-ran distant fourth in a two gun race. Again, that’s my not so humble opinion as a highly opinionated revolver snob.

That Ruger is consistent with their naming of models is, as you noted, is refreshing and explicitly identifies one model from the next: Single Six, Blackhawk, Redhawk, Super Redhawk, the entire 10/22 platform, and so on.

In contrast, trying to keep track of which S&W M&P is which: The fixed sight K-Frame, the multiple generations of plastic tanfastics, their AR clones, and performance center specials, gets tiring. Colt is even crazier going from the 1950’s Cobra .38 Snub to the AA Frame King Cobra of the 1980s-1990s, and now the latest Cobra, King Cobra . . . which snake is which, and will the real Cobra please coil up and hiss.

My older Super Single Six Convertible and Blackhawk .357/9mm Convertible get more range time than any of my other toys. ( 9m/m in the Blackhawk is particularly economical ). They will consume anything I can feed them, and only if the ammo is deflective will they not fire.

That’s my story and I’m stickin’ to it.

“Will the real Cobra please coil up and hiss.”

That has to be my favorite comment of all time! Bravo, Sir!!!! 😁

As much as I enjoy my Ruger single-action revolvers, s. bond, I’ve certainly had some problems with almost all of them. The exception is my Single-Six. The others’ (two .44 Magnums and a .22 Single-Ten) actions jammed up tightly and had to be shipped back to the factory. The .44s’ malfunctions were caused by defective pawls, and Ruger repaired and returned them to me quickly. They’ve worked flawlessly ever since.

The Single-Ten went back to Ruger three times and never could be sorted out, so the company gave me a new Single-Six. So, I’ll stick with that little critter, in his factory condition, reminding myself, “if it ain’t broken, don’t fix it”.

Spencer, sorry about the problem you had with the Single Ten. Both that model and the Single Nine tend to be problematic from the get go mainly because of the geometry required to get 36 and 40 degree rotation increments instead of 60 degree increments. It’s a hit and miss proposition. Ruger has had success with the 10 shot SP101 and GP100 in .22LR since the lock-work is designed around a double action function. Different dynamics without going down the design rabbit hole.

Glad you got the .44s sorted out. Those are great fun to shoot with stepped down reloads.

“Single Action Rugers are, IMNSHO, are the most reliable, most rugged handguns in existence, and the ‘New Model’ versions even moreso.”

Yes, yes, and yes. If it has to 100% go bang with whatever ammo I’ve scrounged, I want my .357 Blackhawk.

I need to try one. Thanks, Mike, for the incentive. I do love my brace of Blackhawks, the guns that turned me on to single-action shooting.

.22 mag is a superb varmint-control round. I have been thinking about a used Single Six. To me, that is the Wrangler’s chief competitor.

Probably so. I hadn’t thought of it that way, but it’s clearly the closest competition from the perspective of quality and performance.

Mike I guess it is the fault of my strong interest in history but I sure do enjoy articles & books about how different guns came to be , how they evolved and their new incarnations.

You and Kevin are masters at this and I hope I get to see a book that you guys have co authored on different popular revolvers.

You sure made me miss the stainless steel Single Six with dual cylinders that I owned many years ago.

Thanks Tony! I think if you tried one of these Super Wranglers, you’d feel right at home with it.

If Heritage can make a 22 Mag on a zinc frame gun Ruger can make one on an aluminum frame gun.

Yep, and it’s selling like hotcakes. The Wranglers are really neat!

Thanks for the good article, Mike. I got my handgun start with a Single Six also, a blued 4 5/8″ barrel convertible. It was my dad’s; I would always ask to shoot it when my brother and cousins were plinking with .22 rifles.

I’m glad that Ruger has committed to the Wrangler and Super Wrangler and making decent guns affordable. “Selling like hotcakes” tells me there is a strong market for affordable, quality handguns like the Wrangler and the DA guns from Taurus. Maybe some other companies should take note…

Indeed, Kevin. They’re doing some neat stuff at Ruger, and I’ll be excited to see what they’ve got coming next. It’s probably too much to expect, to have a medium-frame “Six” comeback, but I remain eternally hopeful.

Great review! I shoot double actions more than singles these days (and I might have to blush, admitting that my new LCR might be my favorite firearm), but I do love single actions. The Colts are classics, but the Rugers are my favorites. While my shooting focus has been elsewhere, I really am interested in checking out a Wrangler (or maybe a Super Wrangler) sometime soon. Thanks for helping us enjoy one vicariously.

I’m a double action guy at heart, but this Ruger makes it lots of fun to stray over to the single action side!

The FORCE is calling you, Mike . . . come to the single action side ; )

Haha! I’m not sure about where this is heading. Is there a sequel where I find out that Charlie Askins was actually my father? 😆

I heard Elmer Keith was kin to you, at least that’s what the guy who claimed to be Charles Askins told me. I think he was the one who told me that . . . was that really Charlie ? The waitress told me that’s who she thought he was, but that’s after I woke up. She never did return my wallet.

Great review! Guess what my next handgun will be! I also have trouble seeing black on black, so almost all of my single sixes, nine and tens have fiber optic front and rear sights. FO sights may not be as precise as the original sights since ambient brightness affects the apparent size of the sights. But they certainly help me shoot and hit the “rabbit”, even in poor light. Williams Fire Sights are my go-to sights.

Exciting! Let us know what you think of it, Fred.

I’ve shot a few guns with FO sights, and they certainly do jump out at you! A good solution for aging eyes, like mine. I’ve never been enthusiastic about putting them on a duty gun, but they make lots of sense on a sporting gun like this Super Wrangler.

The .22 magnum and .22 lr have the exact same SAAMI max operating pressure, 24000 psi.

S&W makes the 351c with an aluminum cylinder and frame, a .22 magnum.

The Ruger LCR .22 magnum has an aluminum frame. (and not the poly grip frame).

Thanks GW. “Energy” would have been a better word for me to use than “pressure.” It’s corrected now!

I have a black Wrangler and a silver Super. I got the Wrangler first and I open carry it on the farm while tromping through the woods, fishing, and just pretending to be a rough and tough cow poke. And I liked it so much I considered trading or selling it to get the Super but once I got the Super, I didn’t want to let go of my old one either. I did run into a similar problem with the Hammer on my first one, the hammer wouldn’t let me pull it back and it acted like something was caught. I messed with it and got it to go again and it kept failing after firing one round, I kept fixing and reshooting and then realized the cylinder bar had fallen out at one point. Looking back I think it was not in all the way so things weren’t lining up and causing the whole thing to malfunction. I thankfully found the little bar and made sure it was fully seated and secured by the retainer button and it has not malfunctioned since. Love these single shooters! And I’m excited to try out the Magnum Cylinder after reading this article. I’m also excited to “upgrade” them with some good looking grips, I saw some rosewood grips that look great on the black, and I am still looking into a set for the Silver Super. Thank you for this article and review! Semper Fi!

They’re really fun revolvers, aren’t they Ryan? I’m glad you didn’t get rid of your Wrangler when you bought the Super—at these inexpensive prices, why not grow the stable?

Just a quick note for those with seasoned eyes… I was at the local Tree Fitty *cough* Dolla Tree *cough* and noticed in among the Halloween stuff was glow in the dark orange nail polish. I haven’t tried it yet, but will be putting some on some hard to see front sights some time soon.