The sands of time fall slowly through the neck of the hourglass at the border, and sometimes they stop entirely. Despite the progress made in other parts of the nation by the early part of the 20th Century, the border Southwest of the 1920s to 1940s looked virtually unchanged from the days before the Mexican-American War, almost a hundred years earlier (1846-48). The endless revolutions, bandit wars, cross-border raids, smuggling, looting, livestock theft, lynchings, military invasions, murder, and “normal” border violence disproved any notion that the days of the “Wild West” were over.

The men of the U.S. Border Patrol rode at the center of this violent drama. To survive in this perilous environment, they had to be quick on the trigger and deadly accurate. To improve their odds, they sought the best equipment, and when they couldn’t find it, they designed their own. It was this spirit of ingenuity, born of necessity, that led to major advances in training, firearms, and fighting leather, to include one of the most influential police duty holster designs to ever grace a Sam Browne. This is the story of that holster.

The Border Patrol: Home of the gunfighters

To assert control of the untamed and still hotly-contested border, Congress created the U.S. Border Patrol in 1924. The agency was small, with less than 300 officers assigned to cover the more than 1,800 miles of southwestern frontier with Mexico, but its impact on life at the border, and the gunfighting culture, was significant.

In the 1920s and 1930s, a U.S. Border Patrolman’s working conditions often bore a striking resemblance to those of a Ranger from the previous century. Officers assigned to border outposts rode lonely, hot, 150 mile stretches of the border on horseback, bringing law and order to a land that lacked both. Working in pairs, they chased down armed gangs of up to 40 men, with no radio, no backup, and only their wits and their guns to keep them safe.

Even those in the well-manned district headquarters were constantly outnumbered. In the 1930s, the hotbed border crossing region of El Paso, Texas only had 42 officers to cover more than 185 miles of porous border. The busy officers fought weekly—sometimes daily—battles with smugglers, bandits and desperadoes. Some of these looked more like military engagements than law enforcement actions, with small armies of Mexicans lighting up the river with rifles and machineguns. From 1924 to 1934, the El Paso District alone averaged one gun battle every 17 days for the entire 10 year span, killing an average of at least one smuggler for every week of the decade.

By necessity, the border men and officers from nearby agencies in the region learned to be fast and accurate with their guns. Anything that stood in the way of deadly efficiency had to be eliminated, so the officers of the southwestern border found themselves, as the leading gunfighters of the era, advancing the state of the art in guns, holsters and skill development.

The Evolution of Fightin’ Leather

Prior to the 1920s, holsters were little more than carrying pouches for handguns. The principal concern was having them fall out during activity, so guns rode deep in the holster and were secured by leather thongs (in many civilian versions) or flaps (in the military designs) to ensure they stayed put.

None of these holsters provided a fast draw, however. In an effort to fix this, El Paso, Texas lawman Tom Threepersons worked with legendary holster maker SD Myres to design a holster with a tight fitting, minimalist pouch, that left the trigger guard fully exposed to allow the finger to get on the trigger early. The pouch was cut low at the top to provide full access to the grip (allowing you to get a firing grip with the gun in the holster, instead of having to fish it out, first) and to allow the muzzle to clear the leather quickly on the draw. The pouch, which rode with its open top at belt level, was canted forward to aid in the rapid presentation of the gun.

The Threepersons design was the first duty holster designed with presentation speed as the primary goal. It sacrificed security (it had no retention features, other than the little bit of friction afforded by the tight, skimpy pouch) and stability (due to its higher ride and short tunnel loop) for speed—a tradeoff that a gunfighter like Threepersons was happy to make. Myres began selling the holster to the public around 1932 and continued to refine the design after its introduction.

Elements of the Threepersons design were carried over into an assortment of holsters from various makers that are collectively described as “FBI pattern” holsters, today. In the FBI design, the Threepersons-style pouch was given a slightly higher ride to avoid poking out underneath a garment. To counter the increased difficulty of drawing a gun from a high riding holster that was worn behind the hip for maximum concealability, the forward cant was increased to about 15 degrees.

This 15 degree cant was retained in the uniform duty holster that the legendary Charles Askins, Jr. designed for the Border Patrol in the 1930s. Askins (a national champion shooter, and among the deadliest of the Border Patrol gunfighters) designed a holster that placed the canted pouch at the bottom of a drop loop that made the gun ride low, on the hip. The holster incorporated a steel shank to position the holster and help it keep its shape as it hung from the Sam Browne duty belt. In Askins’ Border Patrol holster, the gun was retained in the unfitted pouch by a snapped hammer strap, conceding a speed advantage for a necessary improvement in security for the uniformed officer. The trigger guard was enclosed in the early versions of this design, but later in the 1940s it was opened up a bit, though not fully.

The fastest gun on the border

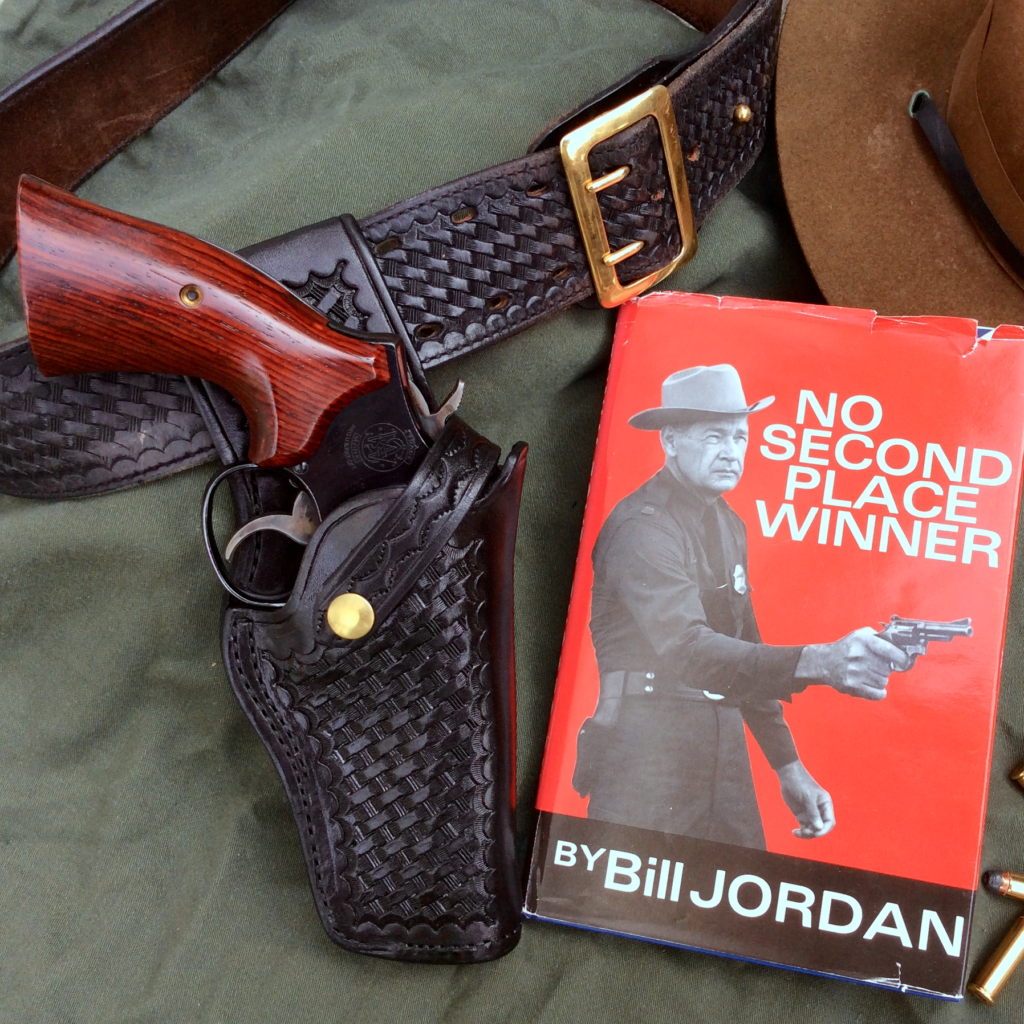

Bill Jordan—a lanky, six and a half foot Louisiana son—got to the Border Patrol a few years behind Askins. He rode the Rio Grande in the violent interwar period, and returned to the Patrol after an interruption to fight with the Marines in World War II.

Jordan was an experienced gunfighter, but also a renowned exhibition shooter, and a record-holding fast draw artist, who could draw and hit a target at 10 feet in 0.27 seconds from the sound of the buzzer (reaction time to shot!) with a double action revolver. Jordan knew about speed, and the importance of being the first to score a hit in a gunfight. He also knew that none of the police duty holsters in existence could give him the speed he wanted, so he designed his own.

Askins’ Border Patrol holster was the starting point for Jordan when he began working on the holster, in conjunction with S.D. Myres, in the 1940s. He had definite opinions on the qualities of a suitable duty rig, to wit:

Here then are the things that a holster should do: It should hold the gun securely yet allow the maximum speed attainable within the limits of comfort, safety, and security. To do this it must be designed to hold the gun in a perpendicular position and, viewed from the front, with the butt straight fore and aft, slanting neither in nor out; the whole weapon pointing straight at the ground with little or no deviation from the vertical. From a Sideview there should be a definite forward slant.

Since Jordan’s principal goal was speed, it was critical for the holster to hold the gun in the same position and orientation, regardless of activity, so that the shooter’s hand could quickly and naturally find it. The drop loop and lower grade leather of the Askins holster allowed it to flop around and shift position on the belt, making the grip of the gun a moving target. This could delay getting a grasp on the weapon, so a higher grade of leather was chosen for the Jordan, and the steel shank in the Askins rig was extended up through the backside of the loop and over the top of the belt, making the entire drop loop a rigid affair that would hold the gun in a fixed position.

That position would present the gun perpendicular to the ground. In the Askins holster, the angle of the gun (as viewed from the front) would follow the curvature of the hip, canting the grip inboard and the muzzle outboard. In the Jordan holster, the rigid steel shank incorporated a curve that held the gun offset from the body, and straight up-and-down. This curve was combined with a twist that held the gun so that the topstrap pointed straight forward, without angling inboard or outboard. Users were encouraged to bend and twist the shank accordingly, to achieve this ride.

In this manner, the gun was perfectly, and consistently, aligned in the drawing plane. It wouldn’t require any adjustment to get it in line as it was drawn. It simply had to be rotated forward so that the muzzle pointed the target. By minimizing unnecessary movement, the gun could be presented with greater speed and efficiency.

The steel shank in the Jordan holster also eliminated the binding that could occur during a draw from a non-rigid design like the Askins, where the holster pouch tried to move along with the gun. The reinforced Jordan rig wouldn’t budge, and its tighter pouch (designed to be more supportive of the gun than the loose-fitting Askins, and hold it in a consistent position) would release the gun more cleanly.

The forward cant of the Askins holster was retained in the Jordan to aid in a speedy presentation, and so was the low cut top that allowed the muzzle to clear leather fast. Jordan was sensitive to shaping the pouch in a manner that protected the gun and its rear sight, which would become increasingly important in the 1950s as adjustable-sighted guns (like the S&W Model 19 that Jordan inspired) became more popular in law enforcement. However, nothing would be allowed to interfere with the grip. To quote Jordan, “. . . the holster should be so fashioned as to get easy access to the butt and trigger . . . in this respect the best description I can give of the desired effect is, when you reach you just get a handful of gun.”

A wedge of leather (later changed to an internal welt) in the pouch helped to maintain the gun’s vertical position in the front-to-rear drawing plane. That wedge/welt also created a gap between the fully-exposed trigger guard and the back of the holster, to allow the shooter to get his finger into the guard and on the trigger early in the draw.

In a nod to practicality, Jordan allowed a safety strap to be added to the speed rig, to help retain the gun during vigorous activity. However, unlike the Askins holster, which placed the strap behind the hammer spur, the strap on the Jordan was positioned so that it was in front of the hammer spur. In this manner, it was easier to clear, and less likely to get trapped and foul the draw.

The Jordan holster was designed to work with a thick, wide gun belt that fit the loop of the holster snugly, to hold it in place without sagging. Leather craftsmen S.D. Myres and Don Hume, who popularized and perfected the Jordan holster design, also fashioned matching, billeted, “Jordan River Belts” that met these requirements, which became almost as popular as the holster itself.

The Jordan holster represented a significant advance in quality of manufacture and design. In an era where some commonly-used police rigs were called “suicide holsters” for their numerous design and material flaws, the rock-solid Jordan was an exceptionally welcome replacement.

The Jordan was strong and tough. Some police holsters of the era weren’t, and more than one old timer has a story about the time that the rivet in their swivel holster broke, leaving the holstered gun lying on the seat when they got out of the car. Others could tell you about a cheap holster that was literally torn off their hip in a violent struggle when the leather or stitching gave way. This didn’t happen with the sturdy Jordan rigs.

The forward cant made them comfortable in a seated position and fast to draw from. The design struck a good balance between access, security and speed for the modern day copper.

The great weakness of the Jordan holster was the safety strap which had to be unsnapped before the fast handling qualities of this speed rig could be unleashed. Jordan recognized this from the start, advising:

Most officers normally carry the weapon with the strap over the hammer, removing it only when they feel that quick action might be imminent. This process should be reversed, and the gun snapped in only if strenuous action— running, crawling, climbing a box car, etc.—is anticipated. In such cases there will always be time to secure the gun, whereas there might not be time for unsnapping it if it was needed in a hurry.

This kind of practice may have been suitable at the height of banditry, smuggling and gunplay at the border in the 1930s, but for the majority of American police officers in the last half of the Twentieth Century, it would have been foolhardy, irresponsible, and downright dangerous to go about their duties with the safety strap unsecured. They knew that life on the streets was unpredictable, and danger often came without the warning that Jordan described. They also knew that a sizable number of cops were shot with their own guns, and that Murphy rides in every squad car, constantly looking for an opportunity to hook your gun butt on a steering wheel or seatbelt as you go out the door.

So, the darned strap stayed snapped most of the time, which made it more difficult to get the gun out quickly. Some makers lengthened the tail on the strap so an officer could slide the edge of his thumb or trigger finger underneath it, and pop the snap by sweeping the hand upwards on the way to the grip, but a lot of straps required the officer to claw it open with the fingertips, and dump it out of the way before drawing. This was an operation fraught with error, proving that Jordan was correct when he said, “there is no way to draw a gun secured by a safety strap without running a risk of winding up with your fingers full of strap.”

When things looked like they were getting dicey, some officers would unstrap the gun to avoid this, and make it ready for a clean draw, but this could increase the risk of losing control of the gun if the situation turned into a wrestling match, instead of a shooting—especially because it could be tricky to snap it back in, quickly.

Cops being cops, a lot of officers would pop the snap before a string of fire during training or qualifications, to simplify and speed the draw. This led to bad habits that could (and sometimes did) doom them to failure when they had to draw for real in the field, with a gun that was snapped in.

So, the strap was a big problem that was never satisfactorily addressed until the vastly superior thumb break (introduced as the “thumbsnap” by John Bianchi in 1958) became more popular, and replaced it, wholesale.

The offset Jordan holster could be awkward for some officers who spent a lot of time in patrol cars, particularly after seat belts became standard equipment in the early 1960s. Fortunately, the forward cant which helped to make the Jordan holster fast, also helped to keep the butt of the gun away from the back rest. It still ran into the seat back, but at least it wasn’t as bad as it could have been with a more neutral cant.

While current doctrine requires a shooter to keep his finger off the trigger until the weapon is aligned on the target, there were no such inhibitions in Jordan’s day, when double action revolvers with heavy triggers reigned supreme, and getting a finger on the trigger early could make a lifesaving difference in speed. Analyzing high-speed photography of Jordan’s draw sequence shows that the lawman got his finger on the trigger at the start, and was already pulling it as the weapon was being oriented to the target, timing the operation so that the hammer fell at almost the exact instant that the gun was properly indexed. This masterful execution of coordination and timing was essential to firing the gun at the lightning fast speeds demonstrated by Jordan.

This routine would give a modern day firearms instructor a case of the vapors, but it was standard practice back then (and even well into the autopistol era, for many agencies equipped with DA/SA autos). Even so, it occasionally led to negligent discharges and self-inflicted wounds among officers who lacked the skills, expertise and timing of a gunman like Jordan.

The Jordan Holster: An Instant Classic

Despite these issues, the combination of a thoughtful design, quality materials, superior workmanship (Myres, Hume), and the endorsement of a modern day giant with a badge, destined the Jordan holster for success.

Almost immediately, the Jordan became the ne plus ultra of police duty rigs. While other designs enjoyed regional popularity—for example, clamshells and breakfronts on the Left Coast, and abortions like the Jay-Pee on the East Coast—the Jordan holster was the dominant uniformed duty rig in American law enforcement from its introduction through the late 1970s (and even the 1980s, in some areas). Almost every maker of police leather goods had some kind of Jordan variant in their catalog, usually labeled as a “Border Patrol” style.

When the classic Jordan holster was replaced by more modern designs that incorporated thumb break safety straps, retention features, new synthetic materials, and other improvements in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the influence of the earlier design was clear. All of these new rigs still retained a lot of Jordan features. Even today, in the age of the bottom feeder, there isn’t a single drop loop, uniformed duty holster that doesn’t owe some aspect of its design to the Jordan.

Not Done Yet

The Jordan is no longer a viable rig for the modern police officer, but it’s a true classic that changed the course of police holster design, and we continue to stand in its shadow today. One of the many pleasures of being a RevolverGuy is that we get to celebrate the highlights of an America that has since passed. When we shoot a classic revolver, or draw it from a classic holster, we’re connecting in a meaningful way with people, places and history that have been forgotten by most Americans, but are worth remembering.

Revolvers are just plain fun, and RevolverGuys understand there’s value in that, even if they aren’t the cutting edge in technology. Revolvers, and the fine leather holsters crafted to carry them, speak to the soul in a way that plastic autos and holsters never will.

I know I’ll never ride the river under the desert moon in search of smugglers and bandits, but when I strap on my Model 19 in my Jordan holster, I can almost smell the mesquite campfires and hear the whispered voices in the brush on the other side of the riverbank. I can also hear the sage advice of a departed lawman, delivered in a Louisiana drawl, reminding me to think fast and shoot straight, because there’s “no second place winner” in a gunfight.

Sources:

Askins, Colonel Charles. Texans, Guns & History. Winchester Press, 1970.

Askins, Colonel Charles. Unrepentant Sinner. Paladin Press, 1991.

Bianchi, John. Blue Steel & Gunleather. Beinfeld Publishing, 1978.

Jordan, William Henry. No Second Place Winner. Police Bookshelf, 1989.

Thanks for the walk back through time, Mike. You prompted me to go pull my dusty, old copy of No Second Place Winner – was there ever a better title of a book related to gunfighting?! – off the shelf. In an age where everything is so fast and ephemeral, it’s nice to remember the era of blue steel and gunleather. The era when so much of what we know about fighting with sidearms came to critical mass.

Are those some crazy stats about the Border Patrol, or what?! One imagines there never has been such a distillation of gunfighting wisdom as occurred along the dust of the Rio Grande during those long years. It’s no wonder we got men of such stature as Jordan and Askins.

Speaking of Col. Askins, I’m reminded of the hoity-toity embassy party he attended in Saigon in the mid-50’s. After the French debacle, but before Vietnam became the imbroglio for us that it later did. Having to walk a few blocks to the party along rough Saigon streets, the good Colonel tucked a small .380 in his belt. Later, at the party, while standing in a small group with the U.S. ambassador, his little pistol decided to unhinge itself from his belt, skitter down his leg, and clatter loudly across the floor. And as I’m sure the room was full of not-gun people (some things don’t change), one can imagine the embarrassed silence!

I expect the Colonel wished he had a bit of nice gunleather that evening.

Indeed, but I’m willing to bet that the majority of his embarrassment came from the diminutive nature of the armament itself, rather than the exposure! Askins was a “big bore guy” after all, so it must have smarted to be caught with the small bore! What would it do to his reputation? ; ^ )

My original draft of this article started to read like more of a history of the Southwest Border than of the Jordan holster. That period from the early-to-mid-1800s until the mid-1950s was particularly dynamic down there, and there was no shortage of hard men to be found. I find it all fascinating.

Thanks for the great article. I love digging through crates of old leather at gun shows.

Me too, Nick! I’m often more interested in those than the guns I see. Glad you enjoyed it. We’ve got a neat installment in this Fighting Leather series on tap, so stay tuned!

Love my Jordan designed Kirkpatrick BP holsters. Some of the comments from steel shooting companions are heart warming. Although available for semi-autos as well, those holsters look best with a revolver (my opinion, of course). Too, I’ve never had an RO tell me I can’t shoot with that exposed trigger, which would be an absolute ‘No-no’ for any semi-auto shooter (it’s even in the rule book), especially a striker fired handgun.

What really made me chuckle is the first steel event I shot with the Jordan, the RSO told me I could begin with the retainer unsnapped if I wanted. Since I carry the Kirk/Ruger CCW, I told him I won’t- I train the way I intend to fight, despite Uncle Bill’s advice to unsnap. (Well, I would unsnap if I knew when the fight was coming, as Bill says.)

Thanks for the interesting write-up. I’m always tickled pink when I see or read something about the old wheel guns I love.

Glad you enjoyed it Sir! Which Ruger rides in your Jordan?

If you tell me it’s a Security or Speed Six, I’m going to be instantly jealous. ; ^ )

Howdy, Mike;

Don’t intend making you jealous, so will just say that all of them do… but the first is the Police/HP stainless Security Six and its brother the GP100 also has a home in its own Kirkpatrick BP.

If it’ll make you feel better, I haven’t yet made out my will…

Uncle JSW! How’ve you been? I’ve missed you so! ; ^ )

That’s a nifty setup for those two great revolvers. I’d love to see you show up at a match with them, and watch the plastic crowd raise their eyebrows!

Mike

Posting from a position of absolute ignorance (I have fired revolvers and prefer them to automatics, but not often and lord knows not recently), but looking at the movement the arm makes in drawing a gun, why does wearing the gun high make more sense than wearing it low and stabilizing it with a tiedown? If the gun is at your waist, you have to lift your arm and hand to it and then lift them even higher to get it out of the holster, If the gun is worn lower you eliminate some of that movement, don’t you? I’d like to understand this better.

By the way, this post is definitely going in my “writing research” file! Thank you!

Ashley, there are pros and cons for each. From the standpoint of draw efficiency, yes, a lower holster (but not too low) can be an advantage because it places the gun closer to where your hand naturally falls. However, because of the curve of the hip, it also puts the gun farther away from your body, where it can be hard to conceal, and where it bangs into everything. It’s also difficult to wear a holster like that when you’re driving, because it wants to run into the seat (particularly in today’s bucket seats—-it was slightly easier in the bench seat era).

Leg tie downs might be useful in specific applications, but are generally not preferred. Every step you take changes the orientation of the gun when it’s tied to your thigh, so it becomes a bit like trying to hit a moving target when you’re reaching for your gun while moving. The “thigh rigs” you see worn by some soldiers and policemen have leg straps for stability and security, but those are specialty holsters with limited utility for most missions. They carry their guns that low to clear things like external body armor and rappelling harnesses that would make it impractical to carry them on the belt. It’s more about the logistics of finding an open spot for the gun, rather than draw efficiency.

Hope that helps.

I’m curious, are you writing a book? A script? And how did you find us? What were you searching for that led you to this article? I’m always interested in how folks get here.

In your research into Border Patrol history, did you happen to run into any documentation of any Jordan gunfights? I ask the question because I’ve been wondering ever since reading the 1990 AMERICAN HANDGUNNER ANNUAL. Charles Askins had an article titled, “Quaint Characters Along the Way”. Two of the paragraphs talked about Bill Jordan. Askins told of his skill as a trick shooter, then said-“Jordan has written a best seller entitled No Second Place Winner; this is all about how to fight gun battles. After 20 years in the Border Patrol, old Bill finally retired. He never killed a man and never had a gun fight. Sorta like writing about how to win a horse race and never having been on a horse.” Ever since reading that article I’ve wondered if Askins, who was a colorful character, lied, or was he telling the truth? It dawned on me that in the book, there were a number of gunfight anecdotes, all told in the third person. When I first read it, I assumed that at least some of them were Jordan’s personal experiences, but I realized that nowhere in any of Jordan’s writing that I’d seen,(certainly not close to all he’d written) did he ever state that he was in a gunfight. I don’t bring this up to pick on the memory of Bill Jordan, but in the spirit of “inquiring minds want to know”. IF the Askins statement is true, the shooting world years ago made an assumption that grew into legend. I can’t count how many articles I’ve seen over the years with a line similar to “the old Border Patrol gunman, who left his many enemies face down in the dust.” It would be nice if there were some conclusive evidence, one way or the other. Just wondering.

Lee, I’m friends with several people in the industry who knew Jordan well, and they report that Jordan was a veteran of gunfights on the Border Patrol, as well as a veteran of close quarters combat in the Marines. I can’t discuss the details of the stories because they were told in confidence (and they’re not my stories to tell, anyhow), but I have no doubts that Jordan was an experienced veteran.

I think it’s important to point out that while Jordan and Askins both worked for the same agency, and faced many of the same dangers, they were very different men. Askins was not hesitant to share all the details of his exploits in public forums, including the ugly details that were probably better left unreported. Jordan, on the other hand, was much more reserved. I suspect he privately viewed that kind of behavior as ungentlemanly, and contrary to his personal code of ethics.

Jordan certainly understood that it was sometimes necessary to use violence, and was prepared to do so, but he didn’t relish it and he didn’t focus on the gritty details. When it was necessary to share a gunfight story to illustrate an important lesson, he preferred to use deidentified, third-person reports with only the essential details (and those were highly sanitized for the reader). I suspect he was trying to protect the privacy of the persons involved (even if it was himself), and shield them from unwanted attention that would be focused on violent events that were necessary, but regrettable. It’s just the kind of man he was.

Askins was different, and conducted himself in a different manner. I can’t explain why he made the comments that you reported, but I’m confident they were inaccurate. I hope that helps.

I have talked with folks who were members of the gun culture and spent time with all of these folks. One gentleman told me that Askins apparently enjoyed killing people, and perhaps from his viewpoint the fact that Jordan may not have shared that joy somehow made Jordan less than.

Oh yes, Askins wasn’t bashful about his pursuit of man. He relished in telling stories about it, and was a self-described, “unrepentant sinner.” Jordan was a different kind of man entirely. I’m friends with some people who knew both of them closely, and they confirm that the two were cut from different cloth.

There is documentation of one man he killed via negligent discharge in the office: Border Patrol Inspector John A. Rector. You can find him with a quick search on the Officer Down Memorial Page.

That’s a beautiful rig pictured above. Reminds me of growing up in the 70’s with a couple of my schoolfriends whose Dad’s were cops. They all wore those black, basket weave gun belts and holsters. I’d love to have one for my 586. Not so much to wear (obviously)…but just to have for my collection of gear. Anybody know if these are still made, or do I need to find and old, used one on the market?

Brian, please check out the review of the Tex Shoemaker Jordan holster on our site (it’s the next blog in the sequence), where you’ll find links to guys who can set you up with a suitable rig for your 586 (one of my favorite guns, by the way–great choice!).

Thanks for the reply Mike. Will check out and bookmark those sites. Yes…my 586 4″ is as close as my current budget will get me to that “1970’s cop gun” vibe LOL.

Great article Mike. Oddly enough the son and I watched the Bill Jordon part of the Fast and Fancy shooters video produced by Rex Applegate just last night.

Bill was always a very entertaining guy in both print and in his demos for the NRA.

Jim H.

Thank you Sir! Great to see you here at RevolverGuy. Jordan was certainly an amazing–and entertaining–guy!

Thanks for the fascinating article. It was a fun step back in time. I have news for you though, some things evidently never change…I know many a modern-day cop who pushes forward the thumb retention strap on the Safariland 6280 holster when things start looking like they might go sideways. It is not exactly approved or trained, but it is definitely done (I may be one of those offenders myself ;-).

Ha! Yeah, the more things change . . .

Glad to see you here, Doug. I hope you’ll stick around and enjoy the fun. We have a two-part series on another classic police duty holster that’s all written and in the queue. You’ll see it before too long.

Ya, I’m one of the old boys having been a young 21 yr old cop in MN with a S&W 19 4 inch.

Both holster and belt being a Hume along with A DUMP POUCH.

18 rounds total . Wow I still get the chills thinking about all of the ammo and working the north woods alone 8 to 4 am and working 900 sq miles.

What a wonderful revolver. It never let me down

Sir, thanks for writing in! I bet you didn’t have a portable radio or a decent flashlight, either. I think the gear may be the only thing that’s improved in policing, over time. It certainly hasn’t been the leadership!