. . . (at least in that era), Thanks to a Horrific Assault on Law and Order.

If you have studied the history of criminal justice in America, you may have noticed a pendulum effect where public approval of criminals and criminality appears to move from one extreme to the other.

We are currently in a period of extreme anti-law enforcement sentiment, and widespread approval of unlawful behavior. History will likely record this as the strongest of the degenerative shifts we’ve seen, to date. By the same token, I expect the forthcoming shift back toward law and order to be the strongest and most dramatic ever. As folks say, “there’s a limit!” and I believe America has just about reached that point.

Editor’s Note: We are proud to feature another “The Day . . .” story from law enforcement historian, and all-around RevolverGuy, Tony Perrin. Tony has a penchant for introducing us to the men and women behind the gun, and bringing the history alive. We know you’ll enjoy his retelling of this story as much as you’ve enjoyed his others. Thanks Tony!

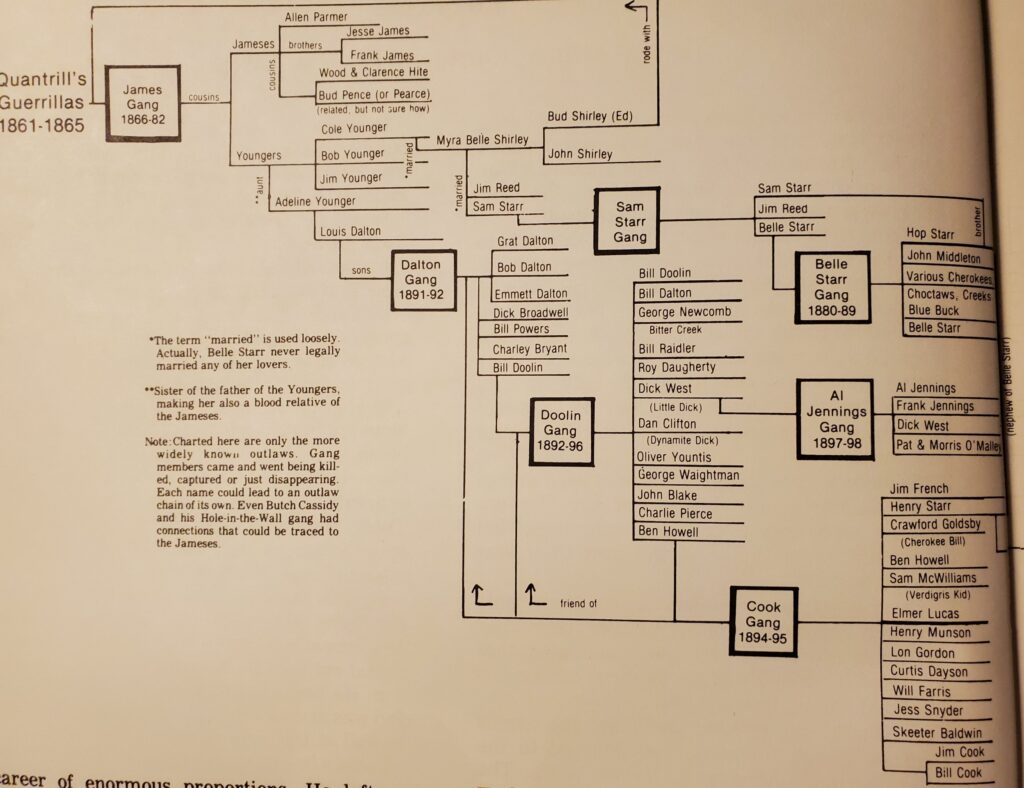

A BLOODY HISTORY

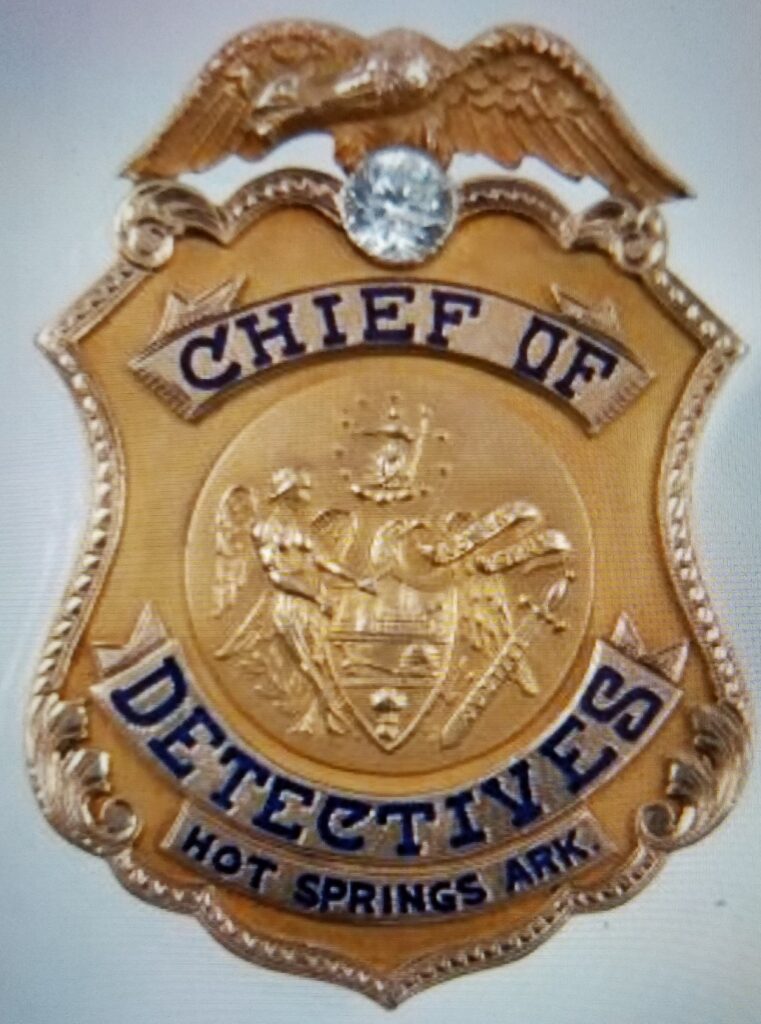

The event we’ll explore here, the so-called, “Union Station Massacre” (alternatively, the “Kansas City Massacre”), involves the deaths of multiple law enforcement officers (LEOs) in the line of duty. There had been others in the same vein, prior to this. Sheriff Charles Gassaway, of Colbert County, Tuscumbia, Alabama, and five deputies died on April 6, 1902, during an arrest attempt. Similarly, on January 2, 1932, Greene County, Springfield, Missouri Sheriff Marcel Hendrix and two deputies, along with Chief of Detectives Tony Oliver and two officers from the Springfield, Missouri Police Department, all died in a shootout with two fugitives. These two incidents account for the most officers killed in a single shootout but it was the Union Station Massacre that served as a pivotal point in the American public’s love affair with the criminal element.

MEET “JELLY”

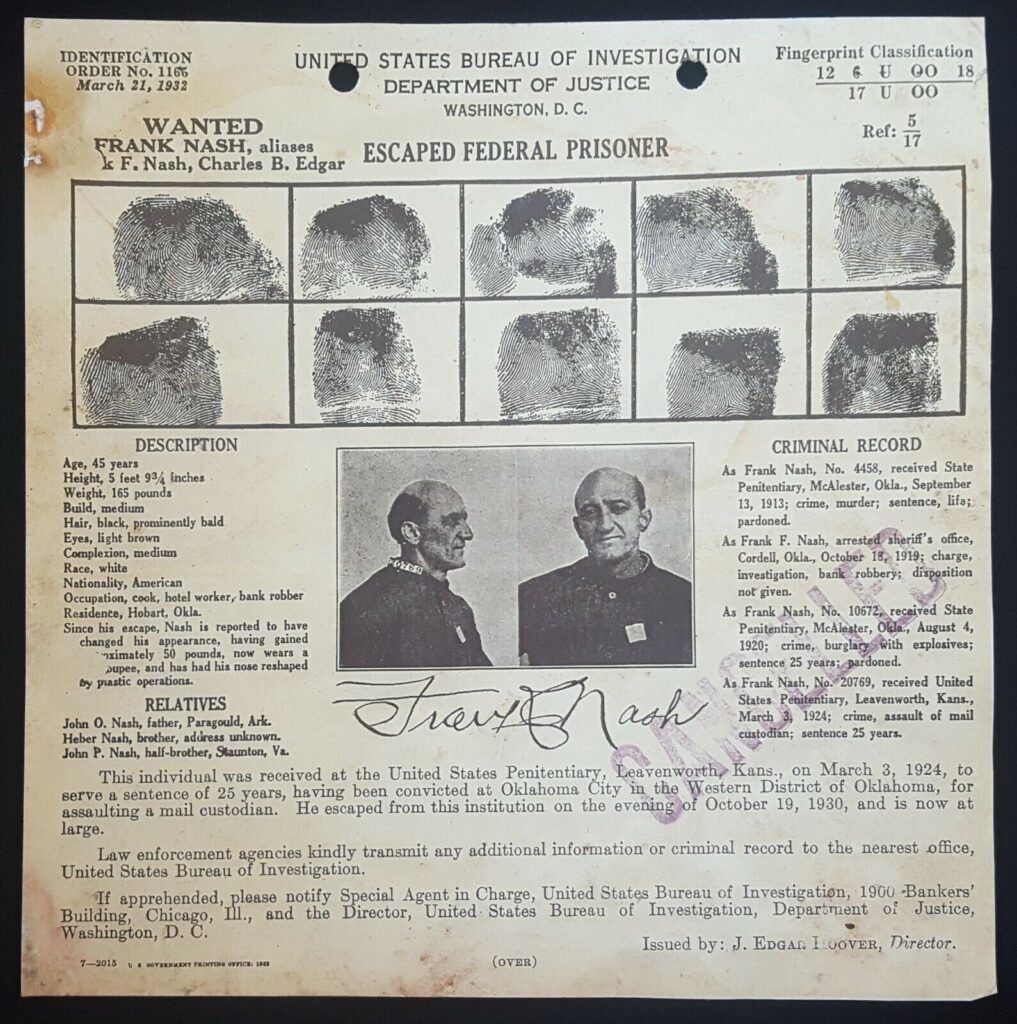

Let’s start the story with the central character of the monumental crime. Frank Nash was born in Birdseye, Indiana on the 6th of February, 1887. In 1893, the family moved to Arkansas, living in Paragould and Jonesboro. In 1899, Frank’s mother passed away, and shortly after, his father moved to Hobart, Oklahoma Territory. There he entered the hotel business.

At 17 years of age, Frank joined the army and served in the Philippines. On his return home, he worked for his dad, but the young veteran quickly became bored as the hotel handyman. He entered a life of crime and earned his nickname, “Jelly,” from his manner of dress and appearance. In 1911, Frank was charged with burglary. In 1913, he crossed into the big time when he was charged with murder and sentenced to life in prison. However, the governor commuted his sentence to ten years, with five left to serve, due to poor health. As World War I began, many prisoners saw their charges dropped in exchange for entering the military, and Frank was one of them. He served with the 90th Division during the last part of the war.

A DANGEROUS RUN

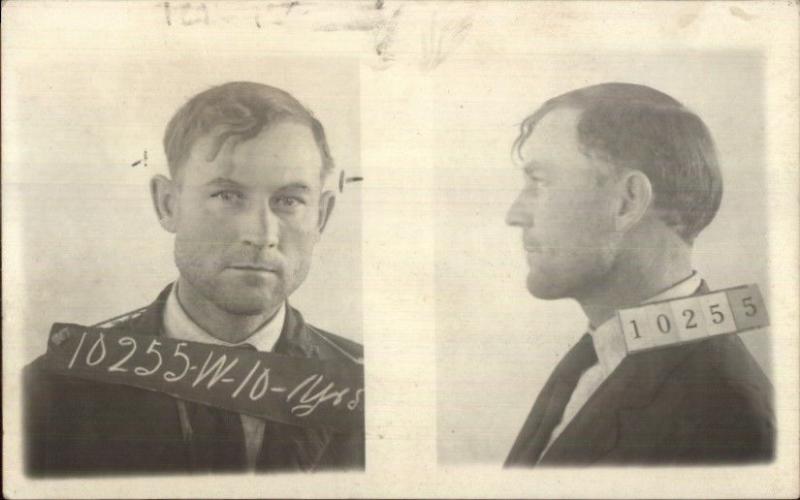

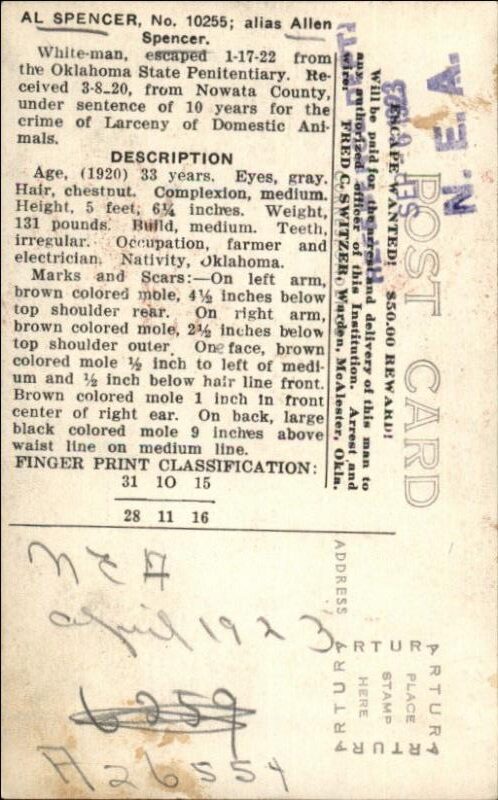

When he returned home, Frank became a bootlegger, and, in 1919, a bank robber. He was soon headed back to Oklahoma State Prison. He established a friendship there with fellow prisoner Al Spencer. This fellow is often referred to as a transitional outlaw, switching with ease from a Colt Single Action revolver to Colt 1911 Government models, and from horseback to automobile.

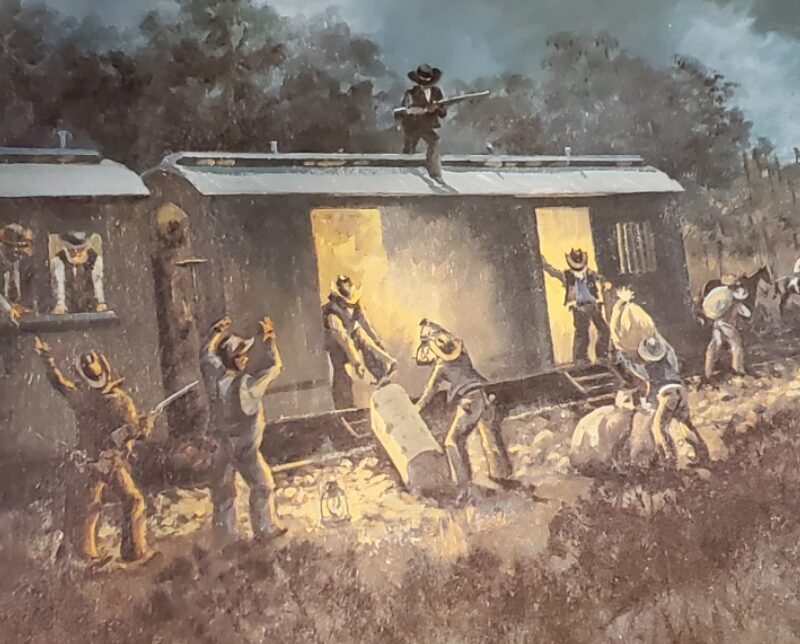

When they were no longer incarcerated, they formed a gang and began a bank robbing spree. Spencer liked his press reports and was known as the “Wild Rider of the Osage.” One reporter mentioned that robbing banks was easier because they were stationary, unlike the James and Dalton Gangs who robbed trains. That comment set in motion the last train robbery in Oklahoma. As he planned the crime, Spencer had Nash invite spectators to watch the Wild West event.

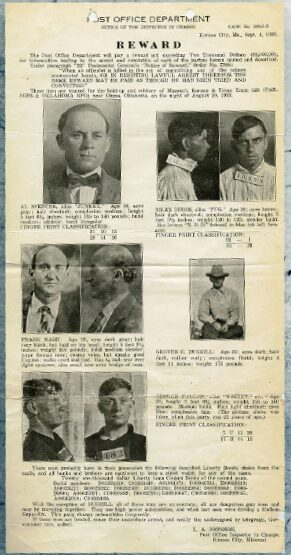

On August 20, 1923, the gang struck the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad at Okesa, 15 miles west of Bartlesville. Not only was it successful in monetary terms, it stirred up the law enforcement folks. Rewards totaled $10,000.

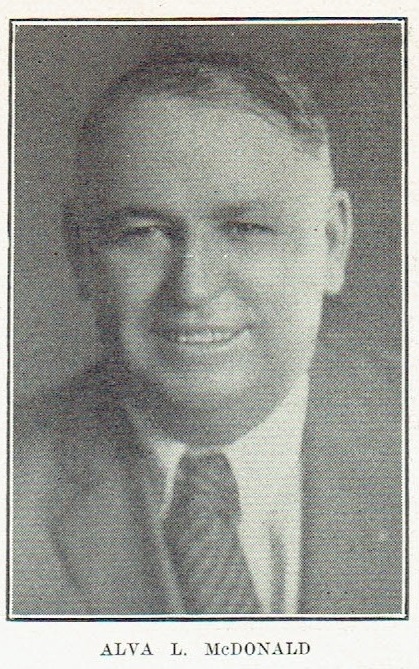

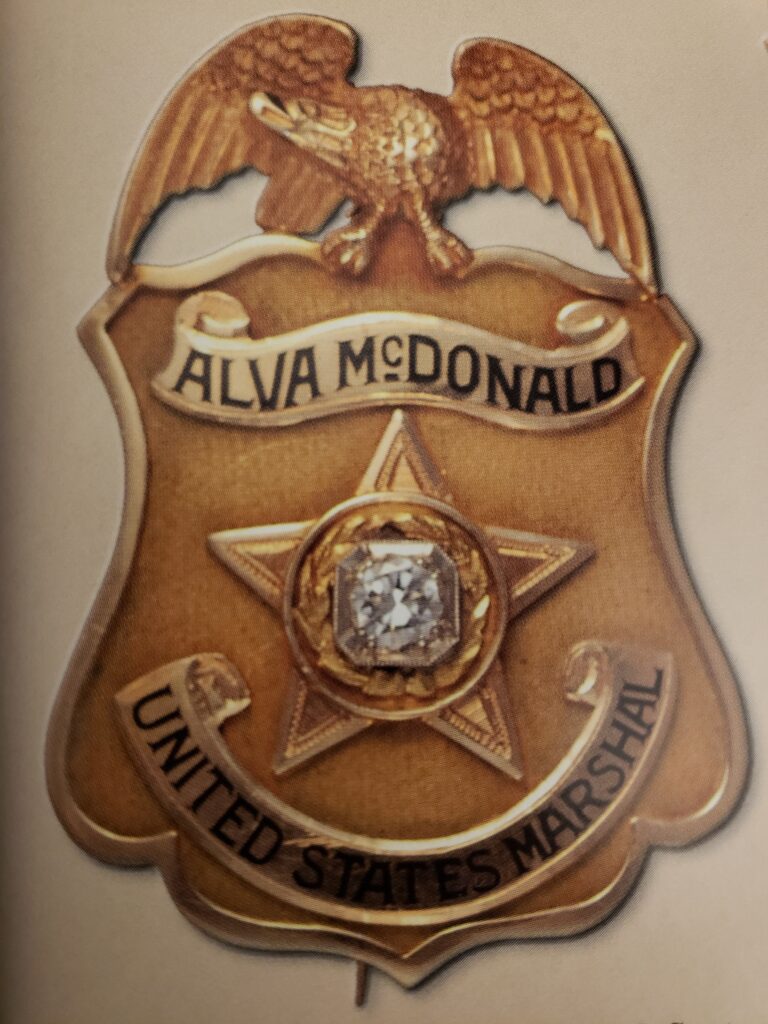

Soon, all of the gang had been captured except Spencer and Nash. On September 15, 1923 U.S. Marshal Alva McDonald, Western District of Oklahoma, led a posse into the hills northwest of Bartlesville. Spencer was walking down a country road when the officers called for him to surrender. He chose to resist and was fatally shot by Deputy U.S. Marshal Luther Bishop.

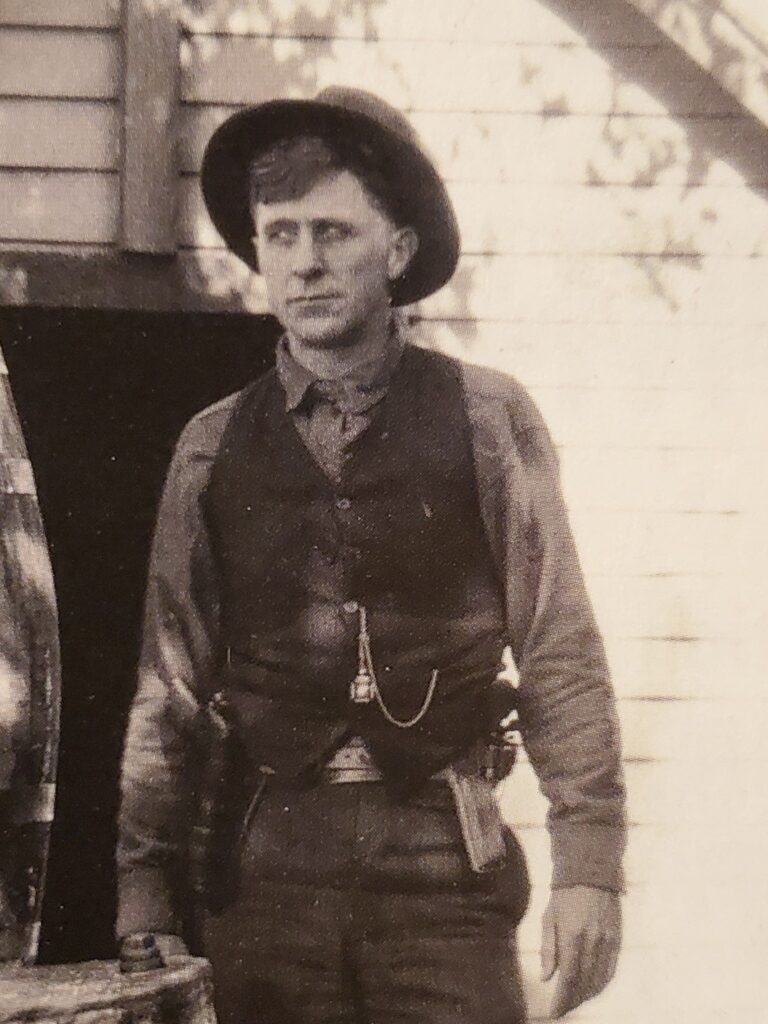

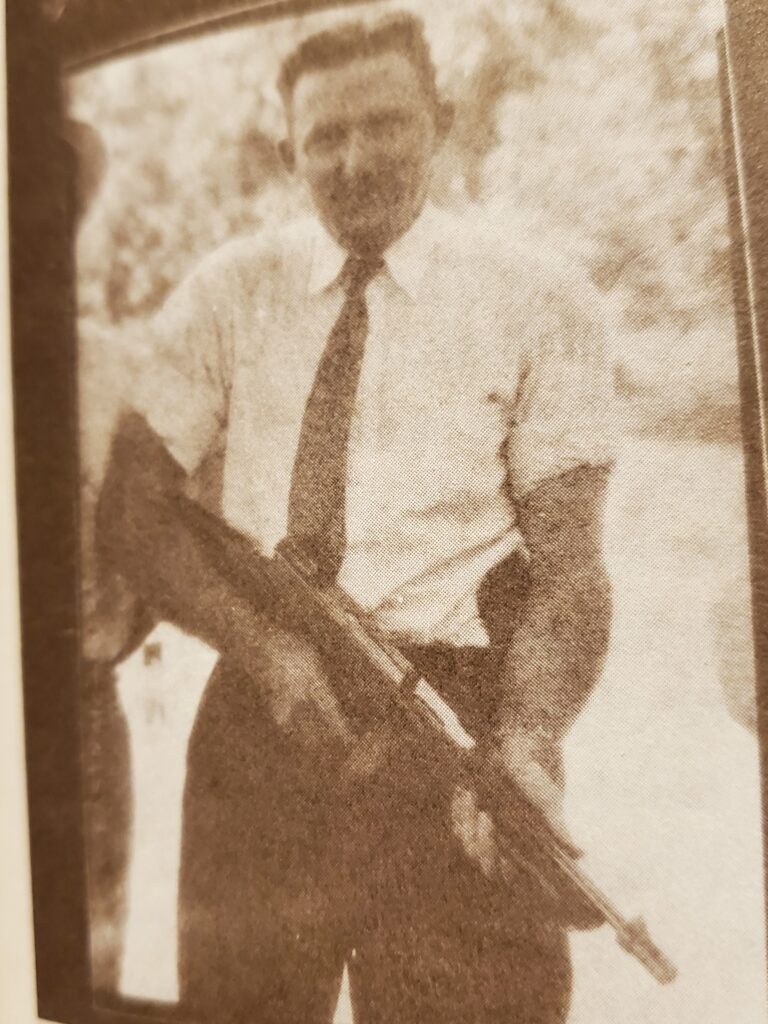

Luther Bishop, incidentally, was a transitional officer, just as Nash was a transitional outlaw. The following image of him illustrates the intersection of old and new technology on his duty belt.

The belt itself is a cartridge belt, with a Mexican loop holster on Bishop’s right side. Inside it is a Colt 1911, most likely a .45 ACP, that is cocked and probably locked. On his left side is a leather pouch added to the belt that holds what appears to be a spare magazine for the 1911. Also, on the left side, inserted into the belt, butt forward, is a Colt Single Action Army, with the belt loops stuffed with cartridges for the SAA.1

CAPTURED, BUT NOT FOR LONG

Information was received that Nash was in Mexico, so a plan was developed to lure him across the river. As he made his way on horseback across the Rio Grande, near El Paso, U.S. Marshal Alva McDonald and other officers were waiting.

Nash was arrested for his involvement in the last train robbery in Oklahoma in 1923. He was convicted and sent to the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth.

By 1930 though, he had achieved trustee status, and walked away from the warden’s residence, where he had served as the cook. After escaping, Nash jumped right back into his crime career, soon to hit both the big time, and a brick wall.

MANHUNT IN HOT SPRINGS

June 16th of 1933 began early for the three lawmen in Hot Springs, Arkansas, after a very short night.

Bureau of Investigations Agents Frank Smith (an alumni of the police departments in Dallas and Fort Worth) and Joe Lackey had left their duty station, Oklahoma City, on June 15th, to follow up on a tip that escaped federal prisoner Frank “Jelly” Nash was in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

Enroute to Hot Springs, the two federal agents decided to stop at McAllister, Oklahoma to enlist the help of Chief of Police Orin “Otto” Henry Reed as he was familiar with Nash. The trio arrived in Hot Springs very late, and after only a couple hours of sleep, set out to locate the fugitive, without notifying the local authorities.2

The trio of officers began cruising the downtown area trying to spot Nash, at the same time paying close attention to the White Front Cigar Store on Central Avenue. The White Front was run by Richard Tallman “Dick” Galatas, who was connected to the criminal element in the midwest. Around 11 a.m., one of the officers noticed Nash park his car and enter the cigar store, a known criminal hangout. Smith, Lackey, and Reed entered the establishment and bought cigars.

When Nash came out of the backroom, he was taken into custody by the armed officers (contrary to popular belief, B.O.I. agents did carry firearms, with the most likely choice being Colt Police Positive revolvers). The officers rapidly escorted Nash outside to their vehicle and began the drive out of town.

SOUNDING THE ALARM

Dick Galatas contacted the city’s crooked Chief of Detectives, Dutch Akers, who he paid for protection. Dutch immediately made calls, fraudulently informing other law enforcement agencies that a kidnapping had occurred in his city. Between Hot Springs and Benton, the officer’s car was stopped by a road block. After showing their credentials they were allowed to continue, only to have the same thing happen on the outskirts of Little Rock.

After the stop at the road block in Little Rock, LRPD Chief of Detectives O.N. Martin called Dutch Akers to inform him that it was not a kidnapping, but instead, federal officers picking up an escapee (which, of course, Akers already knew). With their initial effort foiled, Akers and Galatas began a series of long-distance calls to other outlaws, to set in motion a plan to free or silence Nash. The three officers, sensing an effort was already underway to free Nash, pushed on to Fort Smith, Arkansas to take a train to Kansas City.

HEAVY HITTERS AND HOSTAGES

On the day Nash was captured in Hot Springs, two noted criminals arrived in the small town of Boliver, Missouri. They went into a garage to get their car worked on.

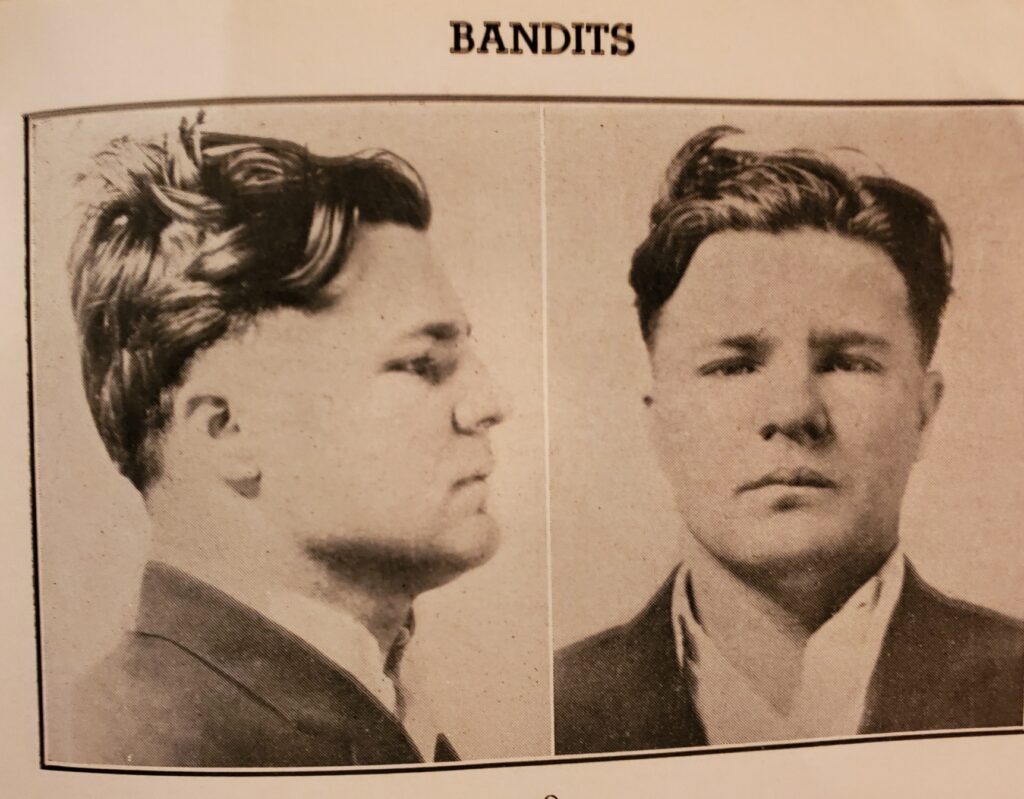

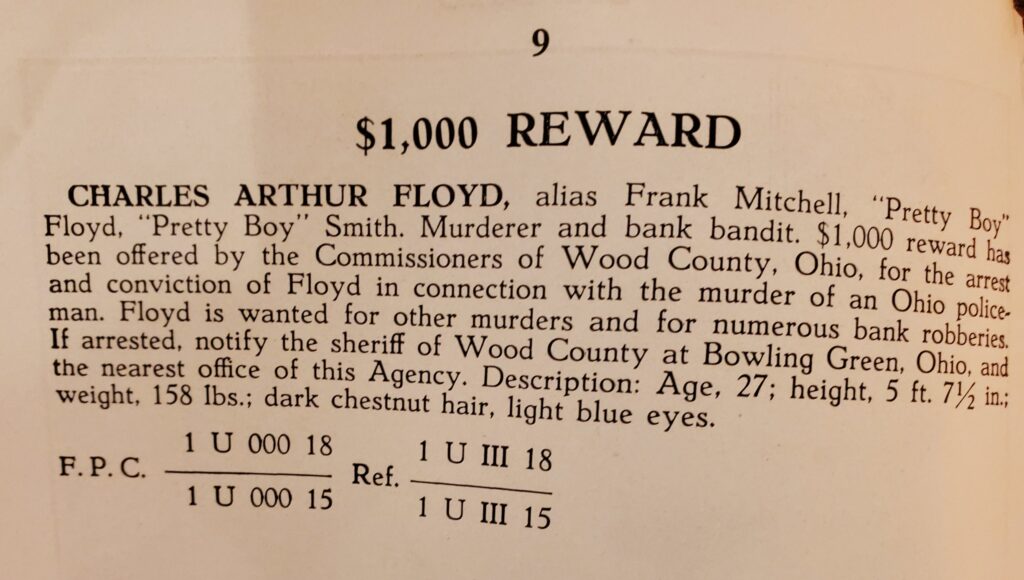

Joe Richetti, the mechanic at the garage, was the brother of one of the criminals — Adam Richetti. The other criminal was Charles A. Floyd, more commonly known as Pretty Boy Floyd, a noted bank robber and cop killer.3

While Richetti and Floyd’s car was being repaired, a man walked into the garage and was recognized as the sheriff of Polk County, Missouri, Jack Killingsworth. The outlaws took the sheriff hostage and left in Joe Richetti’s car.

Shortly after leaving Boliver, the two outlaws decided that the description of the car would be broadcast all over the region. They stopped a motorist, Walter Griffith, took him hostage as well, and commandeered his car.

The four men roamed the back roads that evening until they reached Kansas City. They stopped at 9th and Hickory where Floyd entered a nearby building. The two hostages were told to remain where they sat, as they were being watched, and a short time later, Floyd and Richetti left in another car, driven by someone else. After a while, Sheriff Killingworth and Griffith left, and contacted their families and authorities.

ASSEMBLING A NEW TEAM

As criminals sometimes do, Floyd contacted elements of the mob that controlled Kansas City for help.

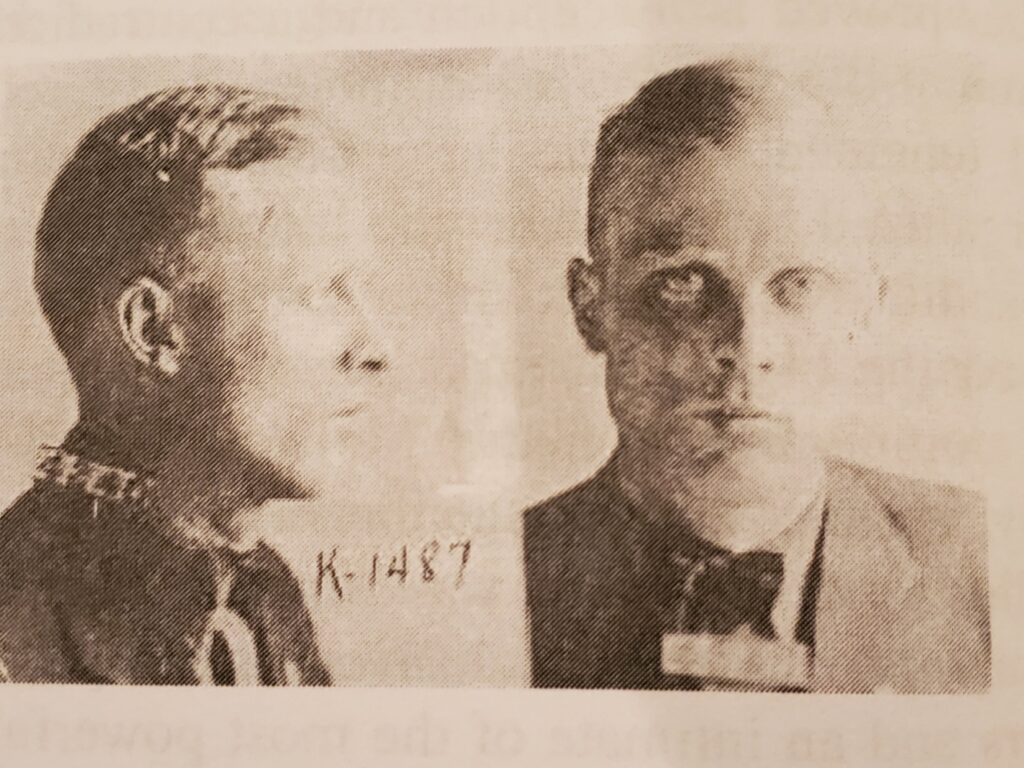

It so happened, that another criminal had sought help from the mob for freeing Nash from federal custody. This criminal, Vern Miller, was from South Dakota. He had joined the army and served with General Pershing’s expedition into Mexico, chasing Pancho Villa. He also served in World War I with the 18th Infantry.

After the war, like many veterans, he entered law enforcement as a member of the Huron Police Department. In 1920, he ran for the sheriff’s office of Beadle County, South Dakota. Miller won that race and served for a couple years before leaving town with more than $2,000 of the county’s tax revenues. He was convicted of embezzlement and served a short term in the State Pen.

After he was paroled, he became a bootlegger. His life in crime saw him shoot and wound two Minneapolis police officers in 1928. He then jumped up to “gun for hire.” After cutting several notches on the stock of his Thompson, he joined heavyweight criminals Harvey Bailey and George “Machine Gun” Kelly in a Minnesota bank robbery. Miller got cross with others involved in the robbery and added three more notches. He continued to rob banks with Bailey, Kelly, Thomas Holden, Frank Keating, Larry De Vol, and Frank Nash. Two Minneapolis P.D. officers were shot and killed by this gang in 1932.

When Miller received word that his buddy Frank Nash had been captured, he went to the Kansas City mob, looking for men to help him rescue Nash. The mob supposedly put Miller, Floyd and Richetti together at a drug store located at Grand and Missouri. The trio then returned to Miller’s house on Edgevale.

THE TRANSFER

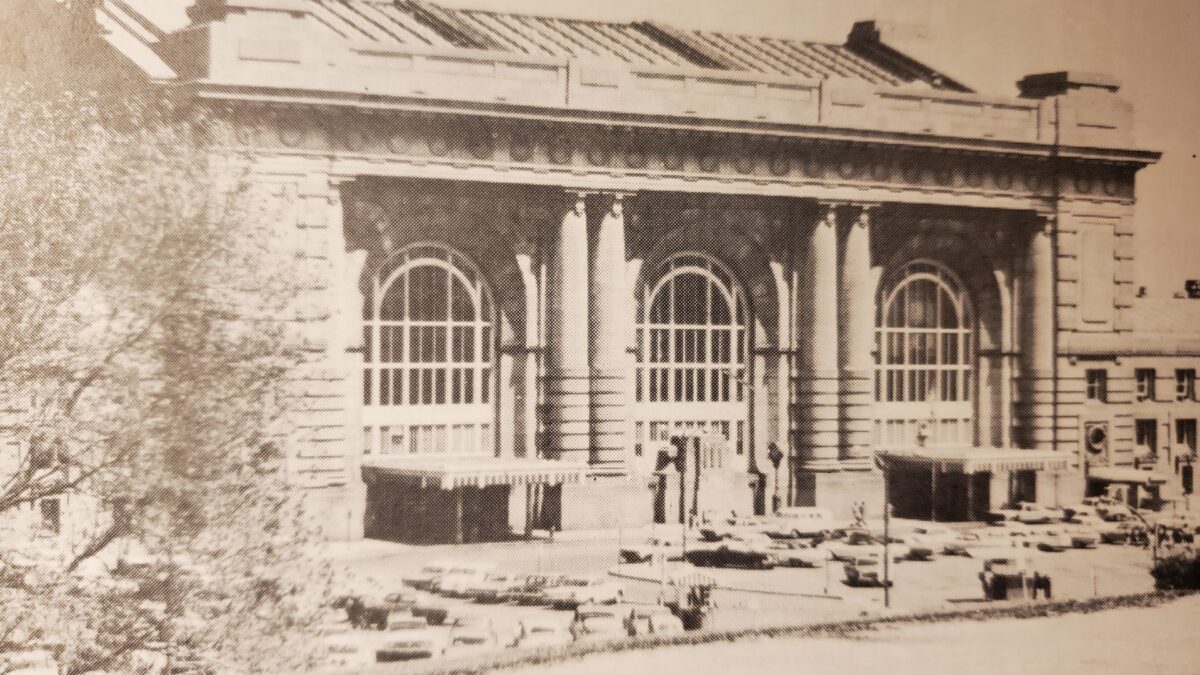

At 7:15 on the morning of June 17, 1933, the passenger train carrying Agents Smith and Lackey, Chief Reed, and Nash, rolled into Union Station, in Kansas City, Missouri.

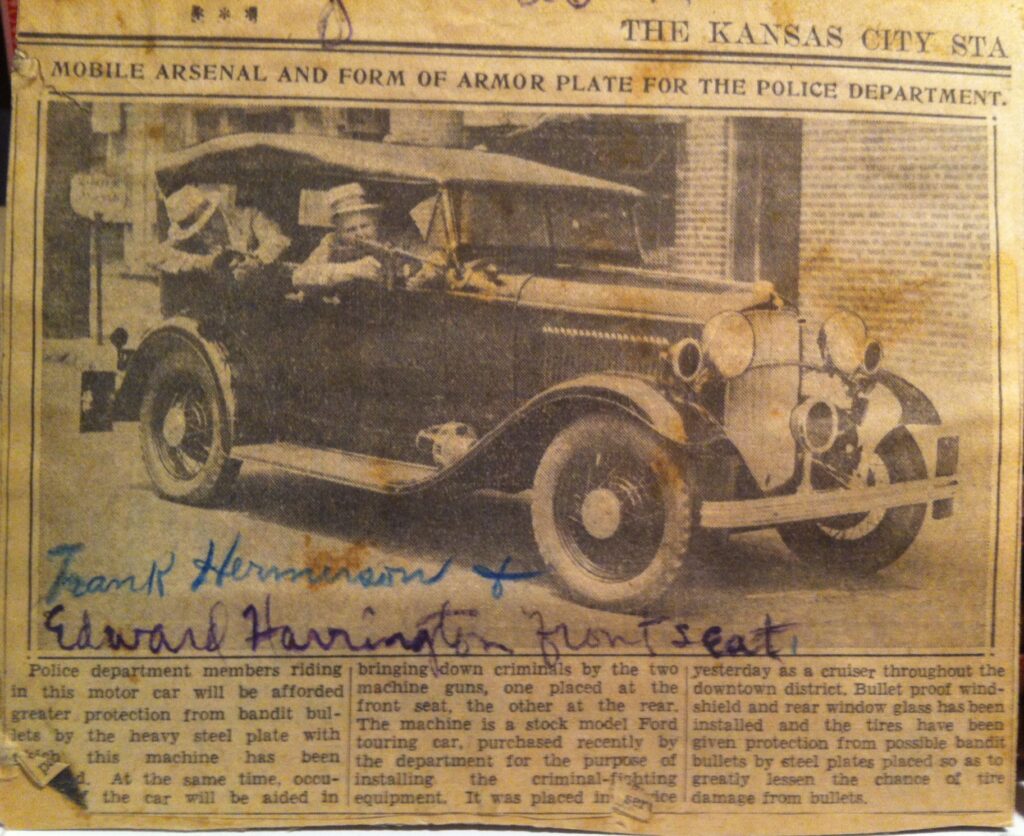

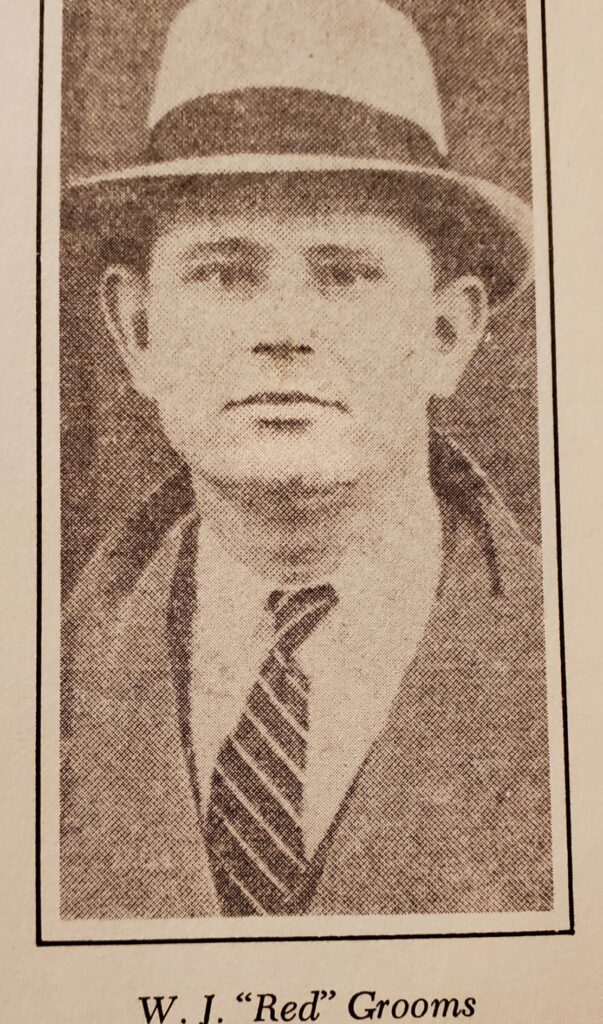

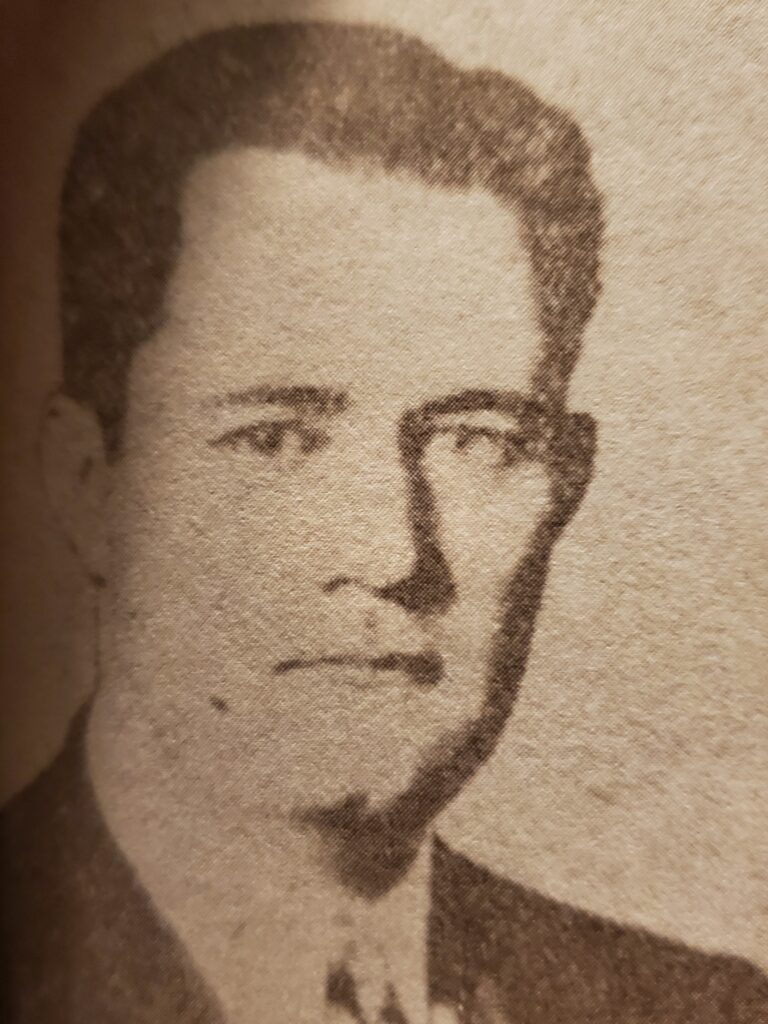

The three lawmen and their prisoner disembarked and were met by reinforcements. Agents from the Kansas City Bureau of Investigation, Reed Vetterli and Raymond Caffery, accompanied by Kansas City Police detectives Frank Hermanson and W.J. “Red” Grooms, met the arrivals on the platform. Grooms and Hermanson had been assigned to assist with the transfer and drove to the station in the departments new “Hot Shot” car equipped with armor and a Thompson submachine gun (which would later be determined to be missing, that day).

The officers formed a wedge formation and escorted their prisoner through Union Station. Once the group exited the building, they moved toward Agent Caffery’s 1932 Chevrolet two door, and proceeded to load into the car.

Detectives Hermanson and Grooms went to the right side of the car to stand guard, as did Agent Reed Vetterli. Caffery took a position on the other side of the car, standing outside the driver’s door. Nash was temporarily seated in the driver’s seat, while the right front seat was folded forward to allow the remaining three officers to enter the rear seat; Agent Lackey in the left rear, Agent Smith in the center, and Chief Reed in the right rear.

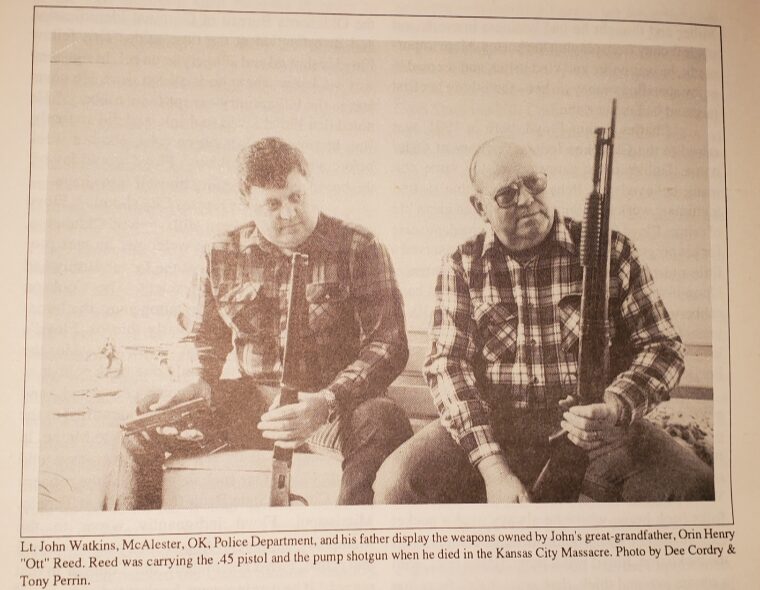

Chief Reed was armed with a 16 Gauge, Winchester Model 12 pump shotgun and a Colt Model 1911, in .45 ACP. Lackey carried a revolver (Colt or S&W) and a shotgun. Smith was armed with a revolver and a 1911 in .45 ACP. Caffery, Hermanson, and Grooms carried revolvers also, leaving Vetterli as the only officer who was not armed.4

THE MASSACRE

When the loading was almost complete, time, and the officers, froze as they heard someone shout, “Up, Up, Get them Up!” Looking around, the officers certainly saw the group of Thompson submachinegun-armed men, pointing their weapons at them from behind the protective cover of cars parked ahead.

The silence and stillness remained in place for seconds that may have seemed like hours. Then the silence was broken by a shout of, “Let them have it!” Next, a thunderous barrage of shots poured from the muzzles of the Tommy guns.

When the shooting stopped, Ray Caffrey was mortally wounded (he would later die, before entering the hospital). Detectives Hermanson and Grooms, and Chief Reed, were all dead at the scene. Agent Lackey and Agent Vetterli were seriously wounded. Only Agent Smith was not hit by gunfire.

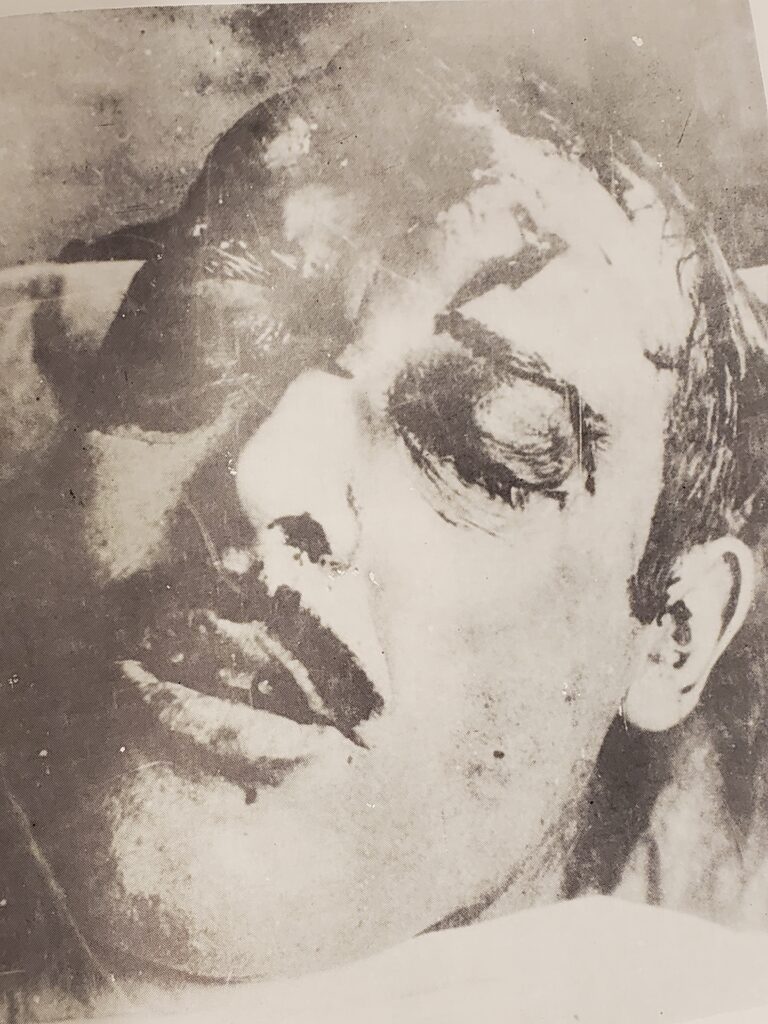

Frank Nash was dead in the front seat of the car with an apparent wound to the back of the head, that exited through the front.

A massive crowd overran the crime scene within mere minutes of the last shot fired. There was no way to control the integrity of the scene, and it is certain that evidence was lost, moved or contaminated.

ANALYSIS

There have been arguments and disagreements about the event since it occurred. These disagreements include who the perpetrators were, who shot who, the sequence of events, and more.

A couple of things are certain. First, opinions are like backsides; everybody has one. The second is that four brave officers lost their lives that day, as did one criminal.

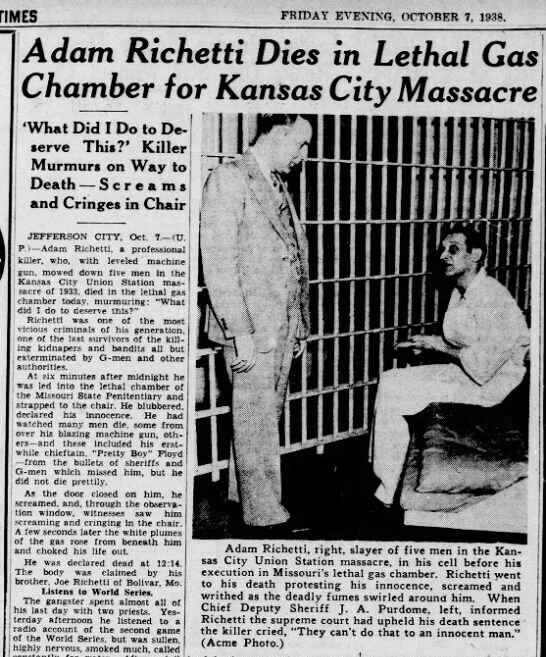

My opinion is that Vern Miller wanted to help his friend Nash (honor among thieves) and free him. I believe that Floyd and Richetti were involved. The theory that Richetti was extremely drunk the night before, and too hungover, may have roots. If that is true, there is living proof that “beer can kill you”—a fingerprint he left behind on a beer bottle got Richetti a date with the gas chamber, at the Missouri Pen.

Another opinion that I hold is that Chief Reed or Agent Smith shot and killed Nash to prevent his escape. One writer thinks Lackey killed Nash with Reed’s shotgun accidentally, but also thinks he accidentally killed Hermanson. If you ever sat the back seat of a 1930s vehicle and have an idea of how long a shotgun is, even with a shortened, 20” barrel, you know that it would be nearly impossible to shoot someone seated directly in front of you, with it. If, by some miracle, you managed to get the shotgun pointed at the head in front of you, and fired, there would be no image of Nash’s face after death. Contact, or near contact, wounds with a shotgun virtually destroy the cranial vault, and Nash suffered no such wound.

INVESTIGATION

The echo of the gunfire had barely cleared the parking lot at Union Station when state and local authorities began trying to identify and apprehend the shooters. As mentioned, the crime scene was chaotic, with no control at all. Officers and agents were shocked, just as bystanders were, that such a savage and brutal assault on the forces of law and order could take place in broad daylight.

“Eyewitness” accounts were gathered and compiled. These showed a great deal of disparity, as two or more people can view the same event and come up with different descriptions. Several of the notorious Depression Desperados were “identified’ as the shooters in the eyewitness statements. One name that was mentioned frequently was Charles Arthur Floyd, and if Charley was there, it was likely that his partner, Adam Richetti, was also.

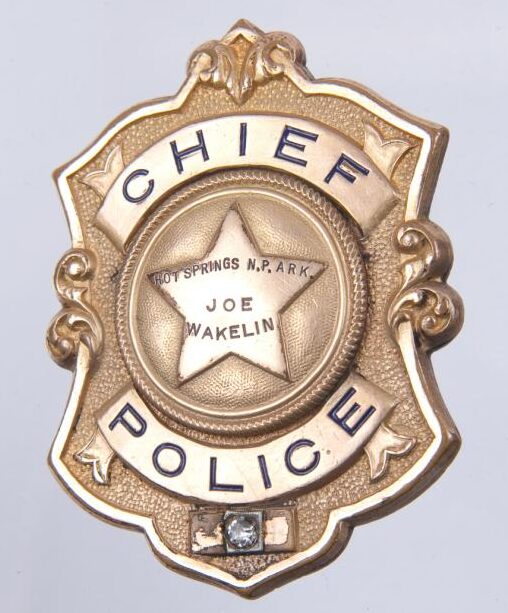

As the federal investigation began under the lead of Agent Gus Jones (a former Texas Ranger who later chose a S&W Registered Magnum as his duty firearm), it soon embraced the technology of the day. Much like tracking cellphones today, their phone records began to reveal a web of calls both inbound and outbound between Hot Springs, Joplin, and Kansas City that showed a conspiracy to free Nash. Eleven individuals were later arrested, including Richard Tallman Galatas, Mrs. Frank Nash, and Herb Farmer of Joplin, for their roles in the crime. Dutch Akers, and his equally-crooked boss, Chief Joe Wakelin, dodged the bullet this time, but would later fall for harboring Alvin Karpis, a key member of the Barker Gang.

The investigation began to focus heavily on Vern Miller, Floyd and Richetti, who vacated Kansas City in haste.

END OF THE ROAD

Miller fled to Chicago, but on November 27, his body was found in a ditch near Detroit. He had been beaten and strangled, but the probable cause of death was bringing too much law enforcement attention to the mob in Kansas City.

Floyd and Richetti, accompanied by two sisters named Baird, wound up in Buffalo. Homesickness, and distaste for the Buffalo winter, spurred them to head back to the midwest. Near Wellsville, Ohio, their car struck a utility pole and was not drivable. Floyd and Richetti sent the Baird sisters with a tow truck to the garage for repairs while they waited in the rural area. Locals saw two men dressed in suits along the road and reported the suspicious pair. Wellsville Chief of Police, Jon Fultz, along with Officers Grover Potts and William Erwin, went to investigate. When they came upon the two strangers, gunfire broke out, and Fultz and Potts were wounded. Floyd fled and escaped, but Richetti was captured.

Stories have been told and disputed ever since that day, but the outcome was that Charles Arthur Floyd was shot and killed. He was returned to his hometown of Akins, Oklahoma and buried in front of a crowd estimated between 20,000 and 40,000 people. He is buried with his parents and his brother, E.W. Floyd, who served as Sheriff of Sequoyah County, Oklahoma from 1949 to 1970.

Stories have been told and disputed ever since that day, but the outcome was that Charles Arthur Floyd was shot and killed. He was returned to his hometown of Akins, Oklahoma and buried in front of a crowd estimated between 20,000 and 40,000 people. He is buried with his parents and his brother, E.W. Floyd, who served as Sheriff of Sequoyah County, Oklahoma from 1949 to 1970.

Richetti went to trial for the murder of KCPD Detective Frank Hermanson in June of 1933. He was found guilty and on October 7th he was executed in Missouri’s new gas chamber.

AFTERMATH

The case against the three alleged shooters at the Kansas City Massacre was officially closed with three deceased. The echoes of the Tommy guns rattled for years with people debating the details of who, what, and how — the same questions that are often not always known even in modern times.

Criminals seek to hide their actions.

This crime did seem to lessen the public’s support for crime and criminals. The pendulum began to swing back, where it remained until the 1960s, before swinging back towards crime again. We hope and pray that we are due for another reset, which will soon return an era of Law & Order.

God bless you and keep you and yours safe!

*****

Special thanks to:

Retired Assistant Chief of Police John Watkins of the McAlister Oklahoma Police Department, and his late Father, who also served with McAlister PD, for their sharing of information and for preserving the firearms that John’s Great Grandfather, McAlister PD Chief of Police, O.H. Reed, carried on that day he lost his life, in the line of duty, in the Kansas City Massacre.

No greater honor can be bestowed on a fallen Officer than for his descendants to follow in his footsteps in law enforcement.

And to:

Dee Cordry, Retired Special Agent of the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation. Dee is also a law enforcement historian and author. His book, Alive if Possible . . . Dead if Necessary details the rich and interesting history of crime and law enforcement in the early days of Oklahoma’s statehood. This book is out of print, but can be found on the used book market, and there are plans for a re-print.

ENDNOTES

-

This is an era when most officers only carried the cartridges (probably green with verdigris) in their revolvers, and no others, but that wouldn’t do for Bishop. Neither was it acceptable to his future partner, Claude Tyler, who reportedly carried small bags of extra ammunition to give to local officers who joined them on arrest attempts. If the name Tyler strikes a chord, think about a small metal grip adapter of the same name that is very popular. It was invented by Claude’s son Melvin, an Oklahoma City PD officer. Maybe his Pop helped him;

-

Hot Springs, Arkansas was one of the “safe” cities for criminals during the 1920s and ‘30s. The wide-open town did not discriminate when it came to the criminal classes. Gangsters such as Al Capone, Meyer Lansky, and Lucky Luciano were welcomed, as were members of the Barker Gang, the Barrows, and Frank Nash — as long as they had money to pay off the police. At one point, the Bureau of Investigation considered Hot Springs Police Department Chief Joe Wakelin and Chief of Detectives Herbert “Dutch” Akers as two of the crookedest cops in America. Needless to say, the agents and Chief Reed did not seek assistance from the local constabulary or even notify them that they were in town searching for a federal fugitive;

-

In fact, Floyd and Richetti were considered possible suspects in the killing of Sergeant Ben Booth of the Missouri Highway Patrol and Boone County Sheriff Roger Wilson just three days earlier in Columbia, Missouri, following a June 14th bank robbery in Mexico, Missouri;

-

There is confusion as to whether the Bureau of Investigation agents were armed or not, but the research conducted by the late, Larry Wack (a retired FBI agent, and law enforcement historian), indicates they were. Before his passing in January 2019, Wack poured his heart and soul into a website of his creation (Faded Glory: Dusty Roads of An FBI Era), which preserves historical documents and contains a great deal of information pertaining to early firearms used by the agency. Thank you, Sir, for your hard work, and important contribution to the history of law enforcement.

Outstanding write-up Tony. Mike said to be on the lookout, and he was right. Here’s hoping that the pendulum swings back to law and order soon.

Blue Lives Matter (too)

DB I also hope it swings back soon before things get totally out of control.

I worry about what will be left behind for younger generations.

Stay safe!

Tony:

I enjoyed your writing about the Kansas City Massacre. Being a retired Cop I always like to read historical accounts of law enforcement encounters with criminals, especially those who are dangerous, like those you tell about in this article. I hate to read of our brothers in blue being killed by those crooks like Nash and his gang, but it does serve to illustrate the dangers of the job.

Dick, this reply is from Tony. We’re having some kind of computer glitch and he’s having difficulty responding to you, so I’m forwarding it as the middle man:

Dick thank you for your service on the front line of the perpetual war for law & Order.

It pains me also as I read about and research line of duty deaths. It also pain me greatly every time I read or hear about the deaths of innocent victims of violent crime.

If there is any benefit from the deaths of Officers it would be lessons learned ( at terrible costs ).

History speaks to us.

Some hear and some don’t.

A classic example is the Newhall Incident, the line of duty deaths of four young California Highway Patrolmen in a single gunfight. Shortly after it occurred it became the engine that drove Officer Survival training to the forefront. Our own Mike Wood wrote the best account of the incident that has ever been penned and I am sure with no way to count or verify there have been untold lives saved by Officers who read the book. Countless teaching points have come from the pages of history.

Two that come to the forefront from Newhall are Felony Traffic Stop protocols and the fact that there are brave, willing citizens like Gary Kness ready and willing to risk their lives coming to the aid of Officers and civilians.

We should never forget those that have given their lives in the war on crime. There are over 20,000 accounted for listed on the national LE memorial in DC and untold hundreds that are lost in the dust covered pages of history waiting to be remembered and honored.

As far as winning the war on crime it will take swift, certain and very serious measures to even get a grip on it.

An anecdote about deterrence:

A friend related a story to me about an event he witnessed in junior high school. The Ozark are somewhat rural and it is not uncomon for a school yard to but up against farm land. Those folks that raise stock sometimes use electric fencing.

In this event some young teenage boys raised a dare for someone to urinate on the fence. Well one fellow met the challenge with spectacular results.

I would bet for the remainder of his life that youngster never has and never will repeat that act.

Great impressions remain in memories for lifetimes and they do shape behaviors.

Stay safe and well in these crazy times we live in.

Tony

I read these sorts of stories, and they remind me that our nation has had plenty of good men (and women, more recently) who have given their lives trying to stop violent criminals. Right now, while there are good police officers and agents who want to do their jobs and stop violent criminals, too often their hands are being tied by inept or crooked leadership. The Bureau itself has become politicized and seems to be more worried about parents concerned about what’s being taught to their kids in school (deeming them “domestic terrorists” for having the audacity to complain) than focusing on violent criminal gangs committing countless heinous acts against the citizenry. I hope and pray that will change in the near future, and get things back to where they ought to be. Thank you for the story, and reminder, that things can change for the better, even if it takes tragic events to force that change.

Tony,

Thanks for another well researched, well written tribute, to our brothers that served before us. These are unfortunately, very trying times for our men and women who get up every day to continue policing their communities and country.

On a lighter note, really enjoyed the picture of Luther Bishop wearing a 1911 and a a SAA in his Mexican “duty belt”!

K.M.C.

Kevin glad you enjoyed the article. Those guys in that transition era were folks its easy to look up to.

You would enjoy the book by Retired Oklahom State Bureau Special Agent Dee Cordry on the early Oklahoma state hood days in LE. Listed in the end notes.

Keep praying for our folks wearing a badge today.

Nice as Told..the good men of America…

Excellent article. In 18 months, I’ll be able to retire. I’ll have been a LEO for 24 years by then. I’ll probably stick around for a couple more years, but it will depend on what is going on. The badge has gotten heavier these past few years.

Hi Tony, great article. I’m hoping to chat or correspond with you about it since I’m researching the same issue.

thanks