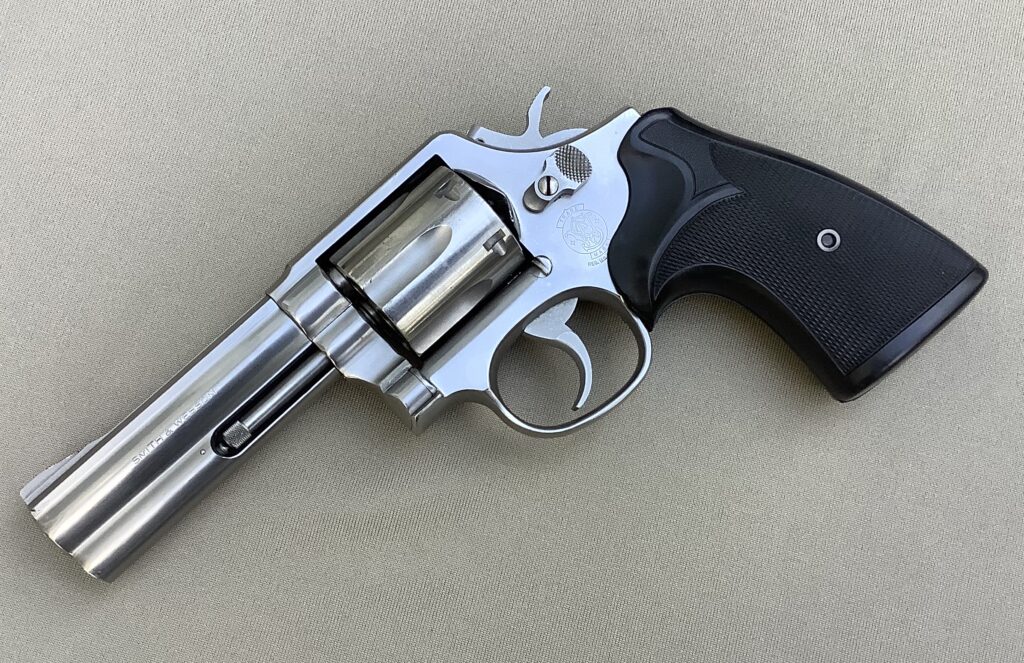

Having previously discussed the development of the Smith & Wesson L-Frame revolvers at length, it seems appropriate to discuss the 1987 recall and modification of these otherwise excellent firearms, which resulted in the “M”-stamped models of the 581, 586, 681 and 686.

A Distinguished Magnum

As you’ll recall from the previous story, the L-Frame was the creation of talented designer Dick Baker, who sought to build a more robust version of the K-Frame, which would handle a steady diet of powerful Magnum ammunition without the barrel cracking issues that plagued the more svelte revolver. His prototype “Super-K” revolvers proved the concept, and eventually matured into the now-classic L-Frame series of guns—the Distinguished Combat Magnums.

The first Distinguished Combat Magnums (and their fixed sight, Distinguished Service Magnum counterparts) were introduced in 1981 and earned a warm reception from revolver fans. The guns were stronger than the K-Frames which preceded them, but retained the outstanding grip frame and trigger reach dimensions which endeared the K-Frames to many generations of shooters.

Here and gone

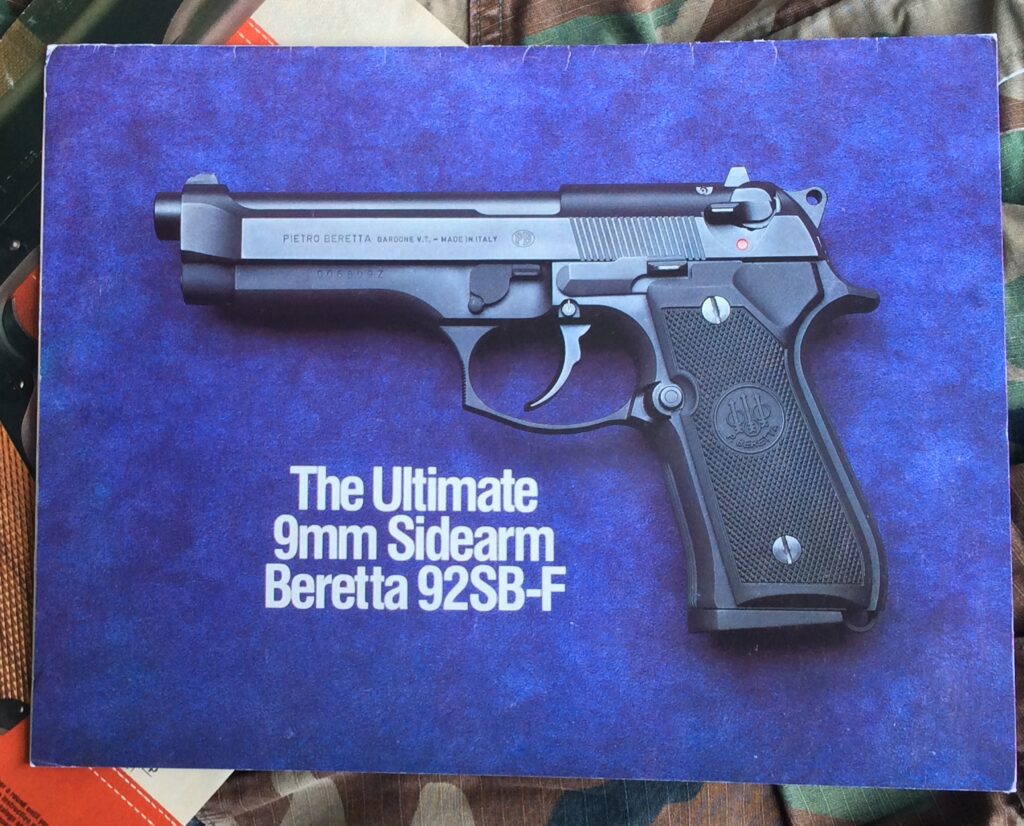

The guns were eagerly adopted by many law enforcement agencies, but sadly didn’t get to serve very long in uniform before they were replaced by autopistols. In 1985, just four years after the L-Frame was introduced, the armed forces of the United States adopted the Beretta M9 pistol, hyper-accelerating a trend which was already taking shape before the L-Frame was born. By the end of the decade, most of the L-Frames in service had been retired for square guns chambered in 9mm (and less frequently, .45 ACP).

Although its service life was cut short, the L-Frame was in use long enough to discover a latent problem. Within a few years of its introduction, it became evident there was an incompatibility between the gun and certain types of ammunition which could render the gun inoperable. This wouldn’t do for Smith & Wesson’s newest service revolver, of course.

All tied up

The specific problem is that the metal cup of the primer used in some brands and loads would flow into the hole of the firing pin bushing when the cartridge was fired, thus binding the cylinder on the gun.

In practice, the firing pin would strike the primer and ignite the cartridge, and the internal pressure in the case would deform the primer cup and cause it to blow out in a circular ring surrounding the nose of the firing pin (or, in Smith & Wesson parlance, the “hammer nose”). This ring of material would flow around the sides of the hammer nose and squeeze into the space between the hammer nose and the interior walls of the firing pin bushing, where the hammer nose poked through the frame. This created a mechanical block which would prevent the cylinder from rotating when the trigger was pulled, and prevent the cylinder from opening when the thumb piece was pushed.

In these failures, there was never very much material poking into the bushing, but there was enough to tie up the works and prevent the gun from working properly. In some cases, applying enough force to the trigger would eventually shear off the offending ring and allow the cylinder to rotate again, but this “remedy” could potentially leave metal shards behind in the bushing which could block or jam the hammer nose on a subsequent pull, or fall into the interior of the frame, where they could cause an even more significant malfunction. Similarly, the frozen cylinder could often be forced open with a sharp smack to the starboard side as the thumb piece was simultaneously pushed, but this risked bending and damaging the yoke, in addition to fouling the piece internally.

In the worst cases, the trigger could not be pulled at all, no matter how much force was applied. In one of the two instances where the author personally experienced a stoppage like this, it didn’t matter how much force was applied to the trigger—it just wouldn’t cycle.

perplexing

One of the things that made this a difficult issue to diagnose is that the problem was inconsistent–it wouldn’t manifest all the time, even with the same gun. It seemed that ammunition selection was a significant factor though, and had a big influence on whether or not this stoppage would occur.

For instance, when the recall was announced, the U.S. Customs Service had already fielded a variant of the L-Frame, and they hadn’t encountered the problem in their guns. Customs had run 20,000 rounds through their test and evaluation samples before approving the gun, and they didn’t see the reverse primer flow issue crop up. Nor did it appear after the guns went into service.

However, that may have been a fortunate byproduct of the ammunition used by Customs. As more data points were collected, and the industry learned more about the problem, it appeared that loads which featured fast-burning powders (and had steep pressure curves) were more likely to bind the gun than cartridges loaded with slower-burning powders. Since Customs had tested their guns with a 158 grain Magnum load, propelled by a slower-burning powder, they simply didn’t see it happen in their guns.

There’s indications that certain “problem loads” were responsible for much of the drama, too. In example, an industry source noted that a major manufacturer’s .357 Magnum 125 grain JHP load developed a reputation in this era for excessive and erratic pressures which were connected to a change in bullet sealant. The sealant (which had previously been used to seal primer pockets, but not bullets) was too sticky, and generated so much resistance that pull forces in excess of 385 pounds were sometimes required to move the bullet out of the case. This generated incredible pressures inside the case after ignition.

The excess pressure cracked forcing cones quickly. In fact, our source advises that he saw brand new K-Frame Smith & Wesson barrels crack in as little as 11 rounds when this particular ammunition was used! In the beefier L-Frame, this pressure didn’t crack forcing cones, but it did seek the path of least resistance, out through the primer hole, and knock the hammer backwards, allowing primer cup material to flow into the firing pin hole in the frame.

It’s important to note that the manufacturer eventually abandoned the use of this sealant, and went to another product that didn’t create such high bullet pull forces and internal pressures, but this was a process that would take some time to play out.

In the meantime, coppers across the United States were left in the difficult position of trying to understand the unpredictable and erratic nature of this problem in their new L-Frame revolvers. While U.S. Customs may not have encountered the problem with the ammunition they used, other agencies weren’t so lucky. Shooting a variety of cartridges from the industry’s most respected brands, their guns were experiencing malfunctions that could be life-threatening if they occurred on duty. A frozen trigger was simply unacceptable in a service gun, and something had to be done about it.

with a little help from my friends

A trusted source has told RevolverGuy that a frustrated Smith & Wesson team contracted with an outside expert for some help in diagnosing the issue with their newest service revolver.

Mr. William C. Davis, a former Small Arms Test Director at the U.S. Army’s Aberdeen Proving Ground, and engineer at the U.S. Army’s Frankford Arsenal, was one of the nation’s leading ballisticians. After retiring from government service, Davis opened Tioga Engineering with his friend and partner Charlie Fagg, a former Rock Island Arsenal weapons engineer. The men and the company had an outstanding reputation in the industry, and were the natural place for Smith & Wesson to go when they needed help with the vexing problem.

Davis apparently determined that the root of the issue was a misplaced hammer pivot pin location. His analysis was that the hammer lacked sufficient mechanical advantage to hold firmly against the base of the cartridge during ignition. Instead of remaining forward, in contact with the primer, as the internal case pressures peaked, the hammer/nose would get pushed rearward as pressures climbed, and thus expose the firing pin hole in the frame bushing. This allowed the primer to flow into the hole, around the nose of the retreating hammer. Davis determined that a slight adjustment in the pivot point for the hammer would allow it to exert enough force against the base of the cartridge that it wouldn’t be moved to the rear as pressures climbed, and the hole in the frame bushing would remain sealed.

A different source, who worked on this project at Smith & Wesson, recalls that Davis simply identified a nagging quality control problem at the company. “The parts were simply out of tolerance,” he recalled. “They weren’t made to the print, which was a very common S&W problem.”

“They hire an outside consultant to tell them, Hey! Make the parts to your own blueprint and they will work!“

Under Pressure

With the reputation of their premiere service revolver at stake, Smith & Wesson took the uncomfortable, but necessary, step of issuing a Product Warning and recalling the affected revolvers to fix the cylinder binding issue. In the recall, Smith & Wesson warned that:

Cylinder binding can result from a number of causes, including characteristics of an individual revolver or the use of ammunition which does not conform to industry pressure specifications or is particularly fast burning. Recent developments in ammunition manufacture emphasize the production of .357 Magnum ammunition with increased velocity and greater primer sensitivity.

This was clearly a nod to the lighter 110 and 125 grain .357 Magnum loads that were increasingly popular during this period. The lightweight bullets in these cartridges were propelled by charges of fast-burning powders which gave steeper pressure curves than the heavier, 158 grain loads that were more traditional choices in the first Magnum. These steep curves exacerbated the primer flow issue by causing internal pressures to peak rapidly, while the hammer nose was still in contact with the primer. As previously noted, this condition could be significantly aggravated by bullet sealants that caused excessive pull forces.

It’s notable that .38 Special cartridges were immune to this problem, because they generated much less pressure than their big brothers. In fact, Smith & Wesson specifically advised in their Product Warning that, “those who need to use their L-Frame revolver . . . prior to modification can safely fire .38 Special ammunition.”

The fix

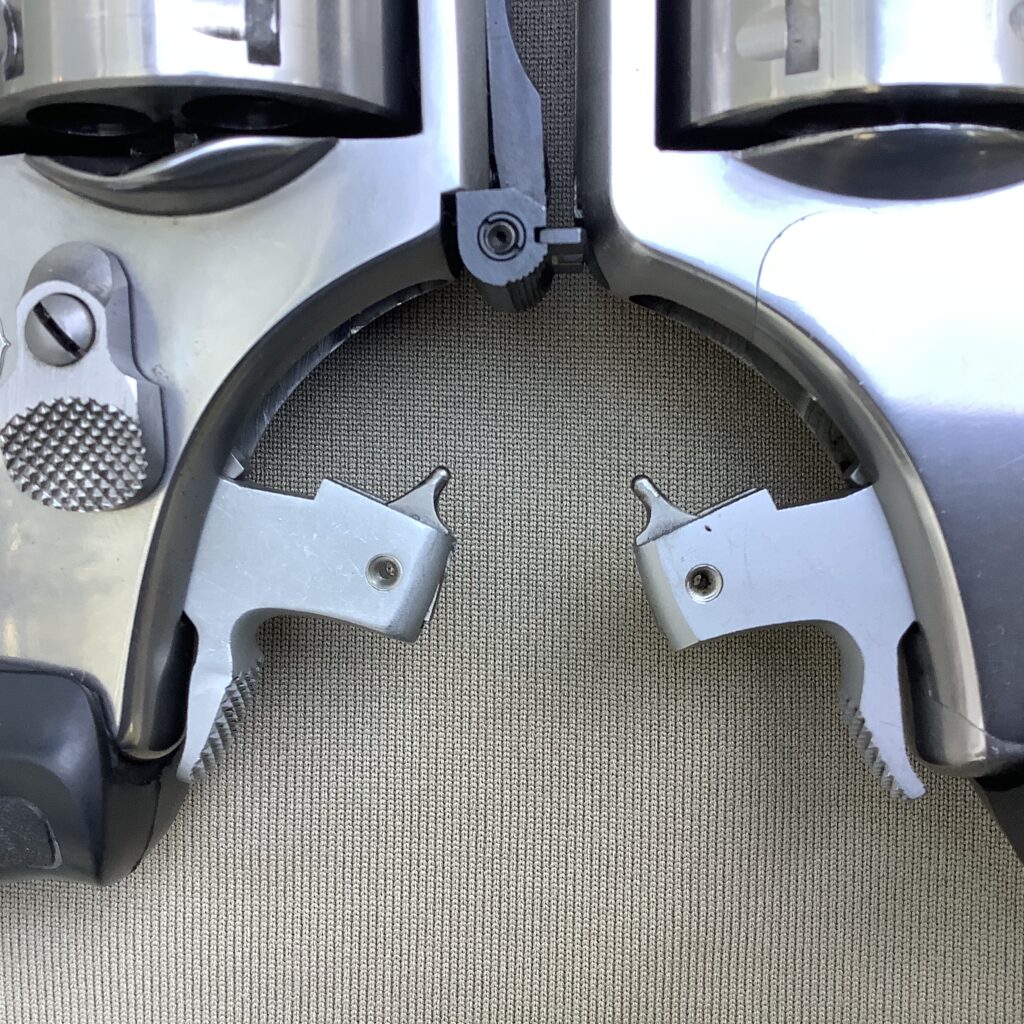

To fix the issue, Smith & Wesson would replace the hammer, hammer nose and firing pin bushing in the affected guns. The hammer nose and corresponding firing pin hole were reduced to eliminate excess clearance, and prevent the backflow of primer material into the frame of the gun. Presumably, the hammer pivot pin hole was either relocated to the place where Baker’s blueprints said it should have been to start with, or to the location that Davis had suggested, if different.

To get this work done, individual owners would have to send their gun to a S&W Warranty Service Center. At first, Smith & Wesson tried to dispatch technicians to large agencies to fix their pool of guns on site, but when it became apparent that the firing pin bushing could not be properly replaced in the field, S&W arranged for agencies to send their guns back to the factory for repair.

The modification made older L-Frame hammer assemblies and hammer noses obsolete, so to ease the pain on gunsmiths and department armorers who had a supply of these parts in inventory, Smith & Wesson offered a return program which allowed them to exchange the old parts for new ones without charge. This did not include the firing pin bushings, however. Although the new L-Frame hammer nose was incompatible with the old bushings, and required the new design bushing, the old bushings could still be safely used on J, K, and N-Frame revolvers, so Smith & Wesson didn’t offer a free exchange on them.

Applicability

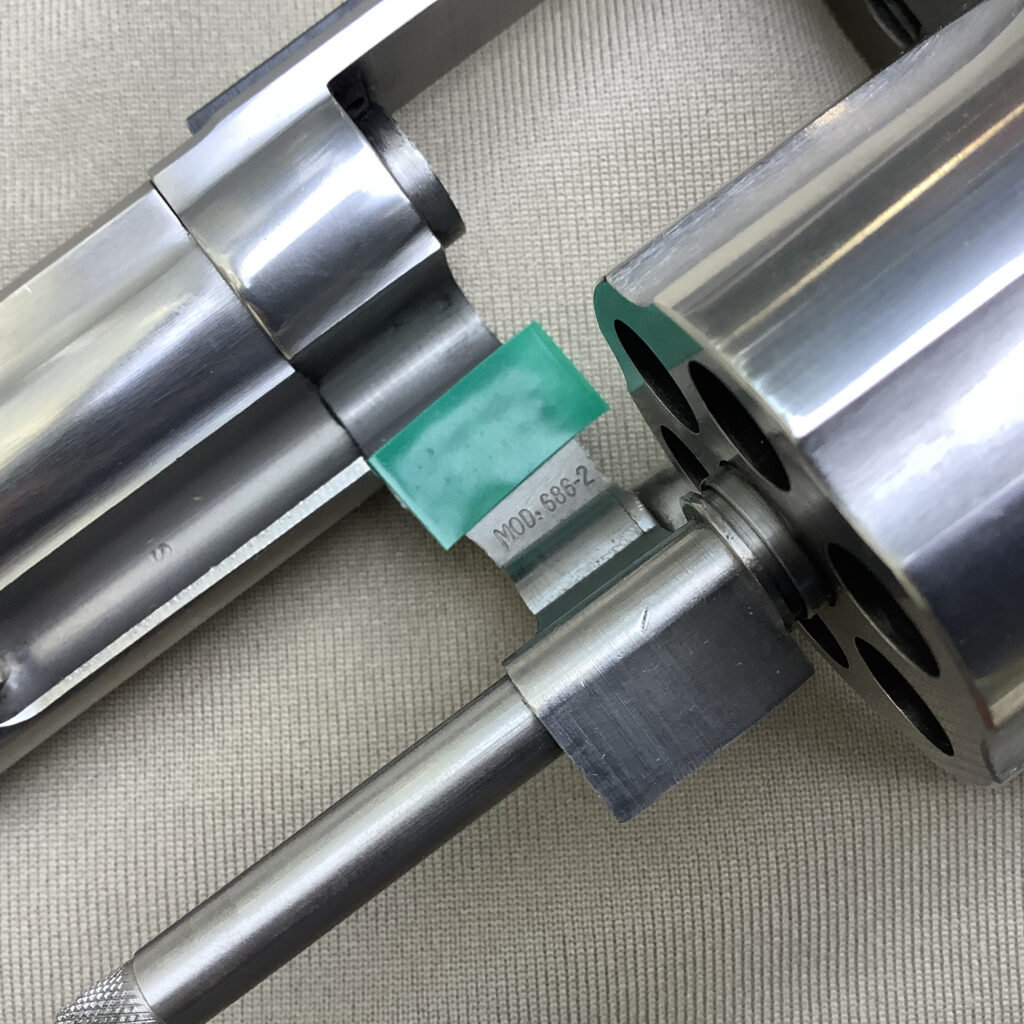

The L-Frame revolvers were new enough at the time that they had only undergone a single engineering (“Dash”) change since they were introduced. Introduced in 1981, the first Dash-1 change didn’t happen until 1986 (Radius stud package, floating hand). As a result, when the 1987 Product Warning was issued, it applied to all “no-Dash” and “Dash-1” models of the 581, 586, 681 and 686 revolvers. Additionally, the special run of 686CS-1 revolvers that were designed for US Customs were also included in the list.

When one of these guns was modified by Smith & Wesson to incorporate the change, they were over stamped with an “M” to denote the service had been performed. Thus, a 686 “no-Dash” became a 686 M, or a 586-1 became a 586-1 M, with the over stamp.

Additionally, Smith & Wesson created a second engineering change for the L-Frames to incorporate the improvements. All new production guns shipped from the factory after 21 August 1987 were marked as “Dash-2” guns (i.e., 686-2) to denote they incorporated the change to the hammer, hammer nose, and bushing.

Today’s owners can thus easily tell if their gun has been modified. Any “no-Dash” or “Dash-1” L-Frame without the “M” overstep has been left unmodified, and any “Dash-2” (or higher) gun was built with the improved parts from the outset.

Should I?

Some of you may have an unmodified gun in your possession and may be wondering if you should still attempt to have it fixed at this late date.

We’re not collectors here at RevolverGuy, so we can’t advise whether or not an unmodified gun would demand greater interest from a collector than one which has been serviced. We like to shoot our guns here, and it seems to us that it would make sense to get an unmodified gun fixed, to ensure it is reliable with all types of ammunition. However, if collecting is your primary mission, then we’ll have to defer to others to help you with your decision.

If you’ve never experienced this malfunction in your gun, and you plan to continue shooting the same kind of ammunition, then you may consider skipping the repair. If you go this route, we’d encourage you to leave notes behind for your heirs with instructions on the ammunition that is known to be compatible with your unmodified gun–no sense passing on the problem to a new owner that might be ignorant of it.

We would personally lean towards fixing the gun, though. An unmodified gun could be a liability, even if it is not used as a defensive arm. When a cylinder binds on a gun, it could easily create an unsafe situation, even under controlled circumstances. So, if you plan on shooting your gun, we’d encourage you to get it fixed–particularly if you’ve experienced this malfunction before, or have plans to shoot Magnum cartridges loaded with fast-burning powders.

WHERE?

Fortunately, it appears that Smith & Wesson Customer Service is still providing this warranty service. When we made a phone inquiry, the representative advised that customers with affected “No-Dash” or “Dash-1” guns could still get the “M” modification completed by the factory. Contact Smith & Wesson through the contact form on their website, or by calling 1-800-331-0852 between 0800-1700 Eastern Time, Monday through Friday, for more details.

In addition to the factory, there’s a few commercial gunsmiths who can also do the work to modify your revolver, if you’d like. It might be a great idea to send your gun to one of these places if you wanted to get some other custom work done at the same time, such as action work, new sights, a new barrel, or something else.

The first we’d recommend would be Bill Laughridge’s crew at Cylinder & Slide. The folks at Cylinder & Slide advise that they can replace the hammer nose and bushing on your gun, but will not modify or replace the hammer. They have the OEM bushing in stock, and use a Power Custom hammer nose kit to accomplish the repair. As of this writing, they will charge you about $50 for parts, $70 for labor to install, and another $35 to test fire. You’ll also have to pay the shipping costs. For more information about this service, shipping rates, and delivery schedule, reach out to them at tech@cylinder-slide.com, 1-800-448-1713, or (402) 721-4277.

Another option would be famed revolver gunsmith Alan Tanaka at AT Custom Gunwork. Alan advises he still has a few of the old parts necessary to complete this modification, and RevolverGuy readers can contact him at info@atcustomgunwork.com, or (310) 327-2721 for more information. Alan’s general pricing schedule can be viewed on his website, but you’ll want to discuss the specific cost of this modification with him when you talk to him.

enjoy!

So, if you ever wondered what the little “M” meant on your L-Frame revolver, now you know!

If you’ve got one of the early guns that missed the modification, give some thought to fixing it. The L-Frames are some of the most enjoyable revolvers to shoot, and when the “M” modification is completed on affected guns, it will make the gun even more enjoyable, by eliminating the possibility of a primer flow stoppage.

Have fun and be safe out there!

*****

RevolverGuy would like to thank our friend “Ed” for allowing us to photograph these beautiful guns from his collection. We appreciate you sharing them with us!

Very good writeup on the great S&W “OOPS” with the early L frame guns. For anyone who might have a no-dash 586 or 686 that has not been ‘upgraded’, they might seriously consider contacting S&W and arranging for the fix. You pay the shipping back to Massagezundheit, they make the upgrade and pay the shipping back. The only way you’ll know things have been changes is the ‘M’ stamped in the yoke. It’s cheap insurance for absolute reliability – and, you don’t have to worry about what ammo might gum up the works..

As much as I love my K frames for carry, the L frame is one really tough gun to beat.

What’s up with the recoil shield on the S&W 681 no-dash? Looks like someone took an angle grinder to it.

Great article, it was a good read and interesting to know about the process S&W went through to figure this issue out. Glad they just didn’t give up and discontinue the model. Bet they learned something going forward on new models!

Makes me want to dig out mine and head to the range! Now ya done it…..!!

Haha! I wondered about that too. Not sure about the story . . . maybe a Monday morning gun?

A lot of S&W revolvers had that ‘cosmetic defect’ during the late 70s through the 80s. With a lot of the early L frames, it was more than likely the result of trying to fill the demand from LEAs for replacements for their K frames. A little skip of this, a little skip of that, good enough for gov’t work sort of thing, it works, now button it up and ship it out.

Keep in mind that the L frame came about as a response to police agencies now qualifying with their carry ammo, and those using .357 Magnums were using the load that tortured the K frame forcing cones into submission. The L frame took care of that issue and resulted in a wide spread switchover.

The cosmetics actually have more to do with asthetics than function; however, the issue that Mike wrote about, and which prompted the recall, was a serious problem. If you follow the time line into the late 1990s, you’ll see that S&W went to frame mounted firing pins which sort of put that issue to rest. Colt and Ruger had been using frame mounted firing pins for decades with great success. It was a matter of time before S&W did the same thing.

That’s a neat observation Stuart, and one I failed to note. Thanks for bringing that up, because it’s the perfect bookend to the story. I hadn’t really drawn the connection between the recall and the frame-mounted pin, but it makes sense.

We’ve got a great audience here! Lots of nollij . . . knawlidg . . . Smarts around here!

Great article, Mike. And thanks to S. Bond and Endofthetrail for the valuable comments. It makes sense that the 681 would look like a Monday morning gun based on it’s probable destination. Probably an LE agency purchase, Cop guns would be the most likely to have cosmetic shortcuts. I have a friend who was a long time employee of Remington’s LE Division and it drove him crazy that product deemed unsuitable for the commercial market would be transferred to LE and sold there. Usually cosmetic, but occasionally functional (Like front sights off center on 870 barrels) issues that were still considered serviceable by bean counters. The average cop that gets issued that 681 or 870 will probably not gripe like the person who ponies up their own hard earned cash for it. As Mr. Bond stated- good enough for govt. work!

That particular 681 had evidence of being dropped on a hard surface, with significant dings on the leading edge of the cylinder. It didn’t get babied. Probably a good thing it had fixed sights! Some guns lead a rough life.

Fifteen years ago I purchased a nice 586 (no dash). I contacted S&W and they provided me with a FedEx order number. I packaged the revolver and FedEx came to my house the day after Thanksgiving 2005 and picked it up. I had my modified 586 back in two weeks. It was delivered to me at work (I’m a police officer) which was where I requested S&W send it. The only thing had to spend money on was the box that I put the revolver and it’s hard-case carrier in. I had the work done for peace of mind. Wasn’t a hassle at all.

Great report Jeff, thanks. Enjoy that beautiful 586!

Interesting. I’ve never heard of that issue before. Had I been alive during the 80’s, I might not have even noticed it due to my preference for .38 Special.

Also, if I may use this as an opportunity to ask, I take it Cylinder & Slide is a reputable business? I’ve never heard of them before, but they offer a fixed rear sight as a replacement for the adjustable sights on a modern K & L Frame S&W revolver like my S&W 69. I’m very intrigued by this option.

Most definitely, Axel. Cylinder & Slide is one of the most trusted operations in the industry. We wouldn’t recommend them, otherwise! That particular sight you mentioned is excellent. I just shot a revolver with one recently and liked it very much.

Thanks for the vote of confidence. I bought one (without dots) and it really was a drop in replacement. Even lines up with the stock front sight. I love it! Really makes my S&W 69 feel like a “combat magnum”. Hopefully I can take it out this weekend to shoot.

Please leave us a report here! I’m very interested to know how the regulation works out.

Glad you bought the one without the dots, as I’m not a fan of the 3-dot arrangements. I prefer an all-black rear and a nice orange front on all my guns.

I have two 686s, one no-dash and ones 686-6. I’ve decided not to repairs my gun as I don’t think it’s worth the hassle. I have friends who shoot theirs often and for years with no problems, even with varying routes of ammo. I doubt any current types of ammo cause problems in non-M stamped guns. If I had many types of old ammo kicking around, I might feel different, but my 686-0 is only in my safe for one reason only, and that’s for collection.

And if I ever shoot it and encounter any problems, hey, that’s what rubber mallets are for!

One more thing. If the end-times come and the Vandals come sniffing at our gates, I have plenty of Security-Sixes that will work and function perfectly! S&W can run all the hamburger ads it wants. All they’ll do is sell steaks and chocolate malts! In fact, I wish you guys would run an article on whether upgrading the Security-Sixes was even necessary. Old-time gun writer Skeeter Skelton claimed to know of three stainless Security-Sixes, each of which he claimed had 300,000 magnum rounds through them. One had some slight timing issues, he writes, but it was still perfectly functional.

That said, I still think the 686 is the best .357 ever made. But if you were going to drop me in any part of the Earth with one .357 and a case of ammo, that gun would be a 6-inch Security-Six!

The Sixes are tough guns, no doubt. I sure miss having them in the catalog. They left a gap that hasn’t been filled. The SP101 is a nice gun, but it’s no Six-series. A 6-shot, .357 Mag SP-series gun would be a good start, but a true medium frame, like the Sixes, would be preferred.

The issue with the L-Frames could be gun-specific. Yours could be fine, and your friend’s could give him fits. Every owner needs to make their own choice, but now they can make an informed decision.

Nice history lesson. I always wondered what the -1 M meant on my 681. I bought it new and it’s still one of my favorite weapons. It has a smooth DA and a very light SA. All stock except for the Pachmayr grips.

You’ve got a great one there, Daniel. Don’t let it go!

I bought my S&W 586 in 1982. I had just been discharged from the Marine Corps and this was my first gun. I’ve shot it through the years without any issues, mostly .38s but occasionally .357s. Was vaguely aware of the recall on it, but never bothered until recently to think about getting the fix, as I was shooting more and more .357s. Called S&W, they sent me a prepaid mailing label, took about 2 months to fix it and return it. I understand the delay in getting it back and they are currently swamped with work due to the huge increase in gun sales. Glad to see S&W still offering to fix the problem more than 30 years after the initial recall, and they paid for shipping both ways. Excellent customer service.

Randy, thank you for the personal testimony about this service. That’s very helpful! Enjoy your beautiful sixgun!

I just purchased a new in the box 686 cs1 with a 3 inch barrel from an estate sale I got it so cheap I’m planning on keeping it and shooting it ,I see none of cs1 Smith’s had the binding problem,that were

listed on the public’s guns ,should I send in for the recall or keep un modified just curious. I’ve seen some Smith’s that looked awesome where the bushing was replaced and some that looked terrible any help would be appreciated.

Vic, I think it mostly comes down to what kind of ammo you’ll be shooting in it. If you’re going to shoot .38s or 158 grain .357 loads, then there’s probably no need to worry about it. If you plan on shooting lots of 110 or 125 grain Magnum loads, then it’s probably not a bad idea to get the modification.

Congrats on a great find!

Thanks for the info.

I’m new to the website, and just wanted to thank everyone for all the useful information.

I own a bunch of revolvers, but my favorite is my no dash 686 6″ that was bought used from a friend in the early 90s for $250.00. I bought it not knowing much about the 686s, but I quickly became my favorite gun to take to the range.

I still have it, and even after thousands of rounds of 38 special, and a few hundred 357s, it’s still looks brand new. More importantly, it still delivers tight groups. My friend told me that revolvers were built to last when I bought it, and he’s been proven right!

Gerry

I would have assumed (probably incorrectly) that the bushing and nose would be the same as the K frames. Why did the K frames not have this issue, and in trying to solve the problem, did Smith look to the K frame for the answer?

It’s a great question, Andrew, and I wish I knew for sure. I’m going to guess that the original L-Frame bushing was the same as that used on the K, but the L hammer nose was unique, for some reason. My suspicion is that S&W changed the L hammer nose profile to make it more robust, knowing that the gun would be eating a steady diet of high pressure Magnum loads (versus the K, which was intended to shoot a lot of Specials, and a just few Magnums). This change, combined with the standard bushing, was apparently a bad mix when certain brands/types of ammo were fired.

I base this on the fact that S&W didn’t offer a return and replacement program for the bushings, because they were still useable on J, K, and N-Frames. That leads me to believe they were common across the frames.

Mike, Best damn write up on the recall issue that I’ve ever seen. Lots of disinformation regarding the recall is floating around, you dispelled all of it on one fell swoop and did a great “public service” to S&W fans in providing such an in depth explanation. Revolverguy.com just gained another follower.

I had the “M” modification done a 686 no-dash I purchased when they first came out, but have chosen not to do it on the other 586/686 L-Frames I’ve acquired in past few years. The cost of now shipping them back to S&W on my dime is prohibitive, and I don’t use anything than standard ammo.

Thank you Sir! Glad we didn’t disappoint! Mind if I ask how you found this article?

It is my understanding that shooting 357 loads lighter than 158gr are to fast and jump the cone gap and causes flash cutting the cone gap

Thanks Terry, we discussed it in detail in a previous post:

The S&W L-Frame Story

Wow. Glad I found this article. I have an original 686 from around 1983. My girlfriend worked for Lear Siegler, who at the time owned Smith and Wesson, so I could get a rather good price on anything. A pilot I worked with flew F-15’s in Alaska in the Air Force. I asked him which gun to get and he hands down recommended the 686 for any kind of survival situation. It’s been a great gun. Never had any problems. Lucky perhaps. Anyway, I’ll be contacting S&W this week to see if this is still covered for the M mod. Great post.

Thanks Karl, let me know what they say. I’ll be eager to get your feedback.

Mike- S&W still does do the mod and were willing to send out a shipping label.

Thanks Karl!

I have been lucky enough to require a 686 “no dash” from a brother-N-law that had purchased the beauty in 1985. He pretty much kept it put away in his collection. Back then they where sold in a cardboard box vs the hard shell case, and the box is just as in great shape as the 686 itself with all the paper work and oil paper within the box still. It has not been modified yet but thinking on having it done. It’s just hard to part ways with this beauty for it has no scratches, dents, are anything else to not be in new condition except being shot less then 12 times (from my brother-n-laws word) and hate to ship it and get damaged!!! It’s probably one of the nicer 686 I’ve had the privilege to put my hands on. It also has the original combat stocks still. I have read where those stocks (grips) are very high sought?? There’s one thing for sure the original stock (grips) on my 686 “no dash”are really beautiful and I can see why they haven’t been changed from there original appearance. Thank you for the read as well. It’s one of the most interesting articles I’ve had the pleasure to read on for sure! I wished there was a way I could show a picture of my 686 on here for I’d love to hear what others opinions was on this gun. Even though I don’t plan on shooting it much I do believe I’m going to have it modified for when my son gets older and I pass it doun to him I’ve will have nothing to worry about any defects. Thanks again for the read Mike!!!

Enjoy that beautiful “new” gun, Andy! Don’t forget to check out the sister article that tells the birth story of your neat gun: The S&W L-Frame Story

Thanks for the detailed explanation and pictures. I recently acquired a nickel 586 that has not had the M stamp mods done, and I will contact S&W re this recall. I want to shoot this beauty!

I very much enjoyed the background insight of the article but was rather suprised by all the paragraphs then devoted to advising having a gun modified to suit defective ammo.

Keep in mind that since the very first .357, owners were advised to test carry ammo in their guns, including hot weather, to make sure the already very high pressure loads were not too high or primer cups thinner/softer than intended, and gun be tied up or blow a primer…old gun press always pointed out that revolvers could be more reliable than autos, but had their own problems with magnum ammo possibly having primer flow and to test ammo by lot for a duty load.

In this case, you had depts beholden to ammo contracts and when contract ammo became problematical, the gun got blamed.

My no-dash/no-M 681 works perfectly with modern Federal 125s, and same with any ammo yet tried, but freely admit I could find some which cratered, but that would not be the fault of the gun. Nobody seems to be suggesting the previous cheap service gun Highway Patrol N-frame be recalled, only because folk stopped carrying them on duty when the lighter Security Six/L-frame/GP-100 became available, and the Highway Patrol had no better hammer QC than the L-frames.

Thanks Bob, appreciate your comments. I think you may have overlooked a few things in the article though.

As I discussed, ammunition selection was a major piece of the puzzle, but there was a gun-related element as well. The L-frame hammers didn’t have proper mechanical advantage to resist the primer flow that some loads encouraged. It’s not correct to assess the problem simply as a defective ammo issue–note that the problem loads shot fine in the N-frame guns, like the M28 you referenced. There were no reports of N-frames choking on the same ammo that vexxed the L-frames, which tells us the guns were part of the problem.

So, the solution follows two paths. You can avoid the problem by careful ammo selection, or you can fix the issue with the gun, to allow greater ammo compatibility. Your choice, and we provided suggestions on how to accomplish both, which seems reasonable to me.