If you hang around RevolverGuys long enough, you will eventually run across a discussion of ejector rod length. It seems that often this will take the form of, “so-and-so revolver doesn’t have a long ejector rod” or “I’ll by X instead of Y because it has a full-length ejector rod.” Frequently this conversation seems to be based around superficial factors, and I’m guilty of this myself.

Today we’re going to dive into the world of ejector rods. You might be surprised by some of the things we found about them. Hopefully, this will help you draw more informed conclusions about revolvers in the future. Based on the research that went into this article, we will also modify how we review revolvers here.

A Note on Terminology: For brevity’s sake I am going to use the term “ejector rod” throughout this article. I realize that some prefer the term “extractor rod” and that it may be more technically correct (at least in some contexts).

The “Longer” Ejector Rod Bias

Among revolver mavens, there is a bias toward guns with longer ejector rods. A gun with a longer rod (there’s no avoiding the innuendo in this post; bear with me!) is generally preferred over a gun with a shorter one. RevolverGuys mostly care about ejector rods because of the real or perceived reliability benefits conveyed.

When reloading a revolver, the first step is to get empty brass out of the cylinder to make way for new cartridges. This is typically accomplished by turning the gun muzzle up and depressing the ejector rod. The brass is extracted by the cartridge rims and ejected, and the chambers are cleared. The longer the ejector rod is, the more positive the ejection (to a point; more on that later) because a smaller portion of each case is left in contact with the chamber at the end of the ejector rod’s travel.

If ejection is insufficient, the portion of brass left inside the chamber may hang up. This results in brass hanging only mostly out of the cylinder, with the rim raised to the point that the extractor star can no longer address it. Correcting this problem requires digitally removing each piece of offending brass before the reload can proceed. This can consume precious seconds, and is obviously undesirable.

Bigger = Better. Or Does it?

Though we aren’t completely wrong in how we think about ejector rods, there are a couple of problems with the “longer is always better” idea. Some of these problems are inherent to the operation of the revolver.

It is possible for an ejector rod to be too long and reach a point of diminishing returns. All other things being equal, an ejector rod that is longer is less rigid and more prone to being bent. An excessively long ejector rod may also be more difficult to operate for users of reload techniques that rely on a thumb to actuate the rod, like the FBI reload. These issues are small potatoes compared the real issue with overly-endowed ejector rods.

Perhaps the biggest danger of a too-long ejector rod is an increased risk of brass or live cartridges falling under the extractor star. This can occur even with short(er) ejector rods when the user “pumps” the ejector rod several times. This is doubly true if the user fails to fully invert the gun, allowing gravity to act on the cases at the “top” of the cylinder.

This condition is made much more likely when the extractor star travels further from the face of the cylinder than the overall length of the brass. While a hung piece of brass can easily be stripped away, clearing brass under the star requires a much more involved remedial action. Two hands are necessary – one to depress the ejector rod and one to remove the brass – and the process takes an unacceptably long time.

Unfortunately, an ejector rod doesn’t even have to extend the full length of the brass to get a case under the star. Brass under the star is possible even with a middling-length ejector rod. More often than not, if a case finds its way under the star in one of these guns, it will still possess a full compliment of primer, powder, and bullet.

Unfired rounds are heavier and smoother than fired brass. They have not expanded under the tremendous pressure of being fired. Gravity can work on the bullet’s weight to pull the entire cartridge below the star much more easily than it can a light, dirty piece of brass. While I’ve never had brass get under the extractor star, I’ve had loaded cartridges get in there a couple times.

Saved From Ourselves

Again, I am guilty of showing a bias toward guns with longer ejector rods. I have also erroneously referred to them as “full-length” ejector rods. without actually defining “full-length” as it relates to the ejector rod. Let’s clear that up now: a full-length ejector rod is one that permits sufficient travel of the extractor star to fully clear brass from the cylinders.

If these guns were on the market many of us would purchase them. Many of us would also unknowingly accept the inherent risk they pose. Manufacturers have largely chosen to save us from ourselves. Of all the revolvers I’ve had the opportunity to fire, I’ve yet to run across one that has a true “full length” ejector rod, with a couple very narrow exceptions. There’s a pretty good reason guns with full-length ejectors are scarce as hen’s teeth.

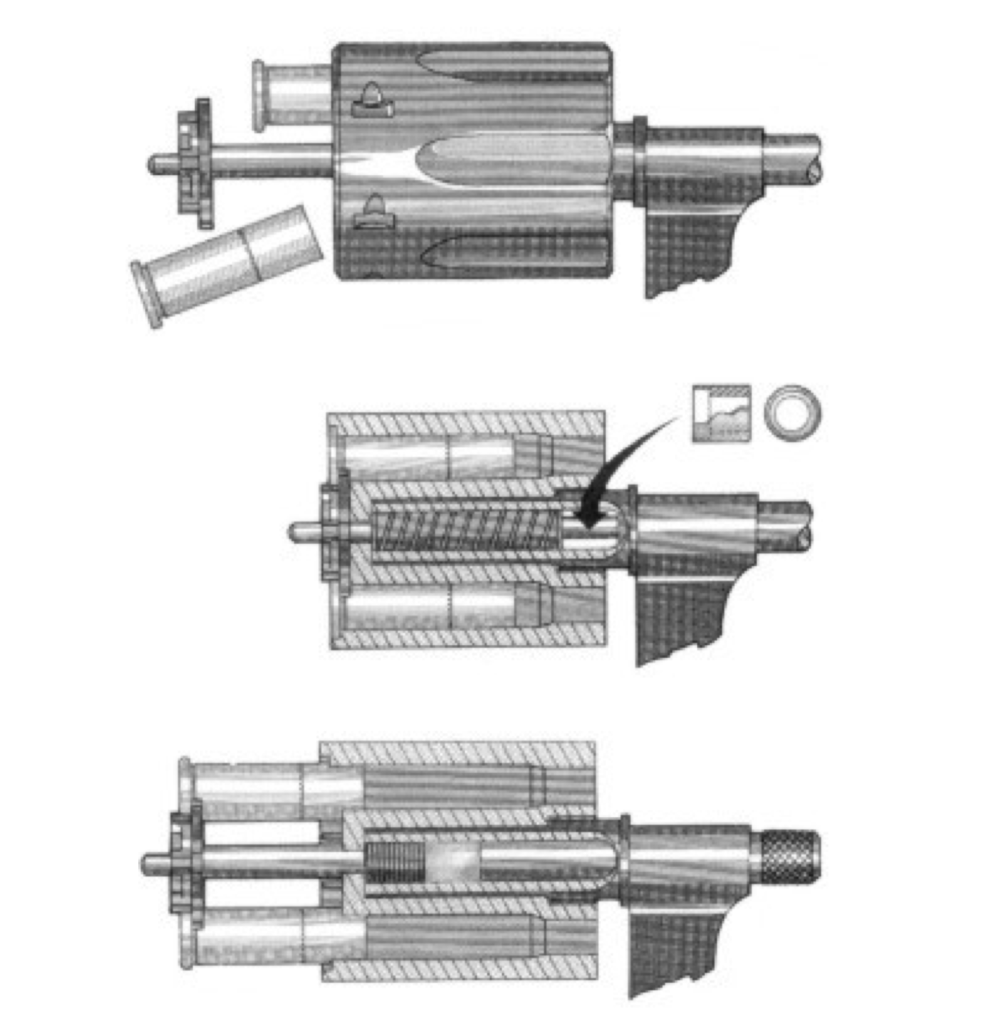

Brass becoming trapped under the extractor star is so potentially dangerous that manufacturers and the aftermarket intervened to lessen their likelihood. Smith & Wesson makes an extractor rod collar for a number of its revolvers. An Extractor Rod Collar was also produced by the aftermarket to mitigate this issue. Aristocrat Products of Covina, CA began producing this product for the same reason S&W started incorporating it into revolvers: to limit ejector rod throw to just shy of full case length.

Of course, there are exceptions to the rule. Mostly notably, revolvers that use moon clips will often fully clear brass from the cylinder. In this instance the danger of a cartridge or brass falling beneath the star are removed. In the case of rimless cartridges it is impossible for the rim to become trapped by the star. More generally, it would be impossible for the entire moon clip to become trapped under the star.

Ejector Rod Throw vs. Ejector Rod Length

If you do a little searching, you will find that my Field Report on the Colt King Cobra drew some negative attention to Colt’s new magnum revolver. There are some complaints that Colt should have equipped this revolver with a longer ejector rod because space for it exists under the longer 3″ barrel. I also heard the same complaint from some regarding Kimber’s 3″ K6s.

This is illustrative of a common phenomenon however, and not unique to the Colt or the Kimber. Unfortunately it isn’t the best way to judge an ejector rod’s effectiveness; visible length is a largely superficial factor. What we’re really after is ejector rod throw. Throw is the distance the extractor star is permitted to travel when the ejector rod is fully depressed.

The visible length of the ejector rod is often a poor indicator of its throw. Some guns with ejector rods that appear very short have impressive throws; I know this because the throw on my 640’s ejector rod rivals that of my much larger 686-3, and bests many larger revolvers. This got me to thinking: how far off the mark are we with regards to simple visual inspection of ejector rods?

Real World Ejector Rod Throws

I measured the ejector rod throws of a few of my guns and became intrigued by the results. I reached out to Mike and a couple of other RevolverGuys including Dean Caputo and asked them to do the same in the interest of acquiring a decent sample size. We ended up with measurements from 21 guns from Colt, Kimber, Ruger, S&W, and Taurus. The ages of these guns spans from a couple of years to several decades. And the results, quite honestly, are surprising. Our basic testing procedure was as follows:

- Place brass in the cylinder,

- Depress the ejector rod to raise the brass to the fullest extent possible,

- Measure and record the gap between the face of the cylinder and the inside rim of the brass (the distance the ejector actually moved the brass)

This testing procedure was something of a three-handed operation, and there is certainly some margin for error. For instance, the 2″ Colt Cobra and the 3″ Colt King Cobra likely have the same ejector rod length, but the measurements reflect a just a few 1/100ths of an inch difference. This could be the result of the technique being slightly different. It could also result from tolerances between the different guns, tolerances in the measuring tools, or tolerances in the brass used. The values listed here should be considered approximate, but accurate enough that we can make some conclusions. All values here are listed in inches and are rounded to the nearest 5/1000ths.

| Revolver | Throw |

| Taurus 856 | 0.550 |

| S&W 640 no-dash .38 | 0.620 |

| S&W Mdl 66 2.5” | 0.740 |

| S&W 66-2, 2.5” | 0.800 |

| Colt Python, 4” | 0.830 |

| Kimber K6s | 0.860 |

| Ruger GP100, 4” | 0.860 |

| New Colt King Cobra 3″ | 0.860 |

| S&W 67-1, 4” (CHP) | 0.865 |

| New Colt Cobra 2” | 0.870 |

| Ruger GP100 MC 10mm | 0.890 |

| S&W 640 Pro Series | 0.890 |

| S&W 610-3, 4″ | 0.935 |

| S&W 686-3 4″ | 0.955 |

| Mod 13-4, 4″ | 0.955 |

| S&W 65-5, 3” | 0.965 |

| S&W 640-3, 2.125” | 0.990 |

| Colt Police Positive, 4” | 1.020 |

| S&W 13-2 3” | 1.020 |

| S&W 66-1, 4” | 1.025 |

| S&W 19-3, 4” | 1.065 |

Again, these results are surprising; looks can be deceiving. As I mentioned earlier, the ejector rod on my 640 Pro is longer than the “full length” ejector rods on both my 10mm GP100 and a friend’s .357 Magnum GP100, a 4″ Colt Python, and at least some 4″ K-Frames. If we looked at those guns would we accuse them of having a “non full-length” ejector rod? Probably not. The Colt King Cobra that got flak for its short ejector rod? It, too has a longer ejector throw than the non-match Champion GP100 and the Python.

Secondly, not one of these revolvers offers a truly “full-length” ejector throw. Just for curiosity, I dug a dozen pieces of once-fired, factory .38 Special brass from my brass bucket. I made sure to select brass from at least half a dozen manufacturers. I then measured the length of the case to the inside edge of the cartridge rim. My average measurement was 1.081″ – longer than the longest length of throw presented here. While I’m 100% confident that revolvers exist with a full length throw, I’m equally confident they’re not super common.

Training, Technique, & Equipment

This information is certainly interesting to me. First, I’ll be far less likely to turn my nose up at guns with an ejector rod that just looks short; in the future I’ll be far more interested in how far the ejector rod travels. Like most people, I like hardware solutions when they are available and appropriate. As my opening paragraphs mentioned though, a true full-length ejector rod creates as many problems as it solves.

And anyhow, guns with true full-length ejector rods just aren’t readily available. To ensure positive ejection I have to rely on some other things. What is most important is my own training and practice in regards to ejection of spent brass. To ensure sufficient extraction and ejection the rod needs to be worked with some vigor. This also prevents the sometimes accompanying problem of “pumping” the ejector rod up and down. Pumping the ejector rod increases the likelihood of brass or a cartridge under the star.

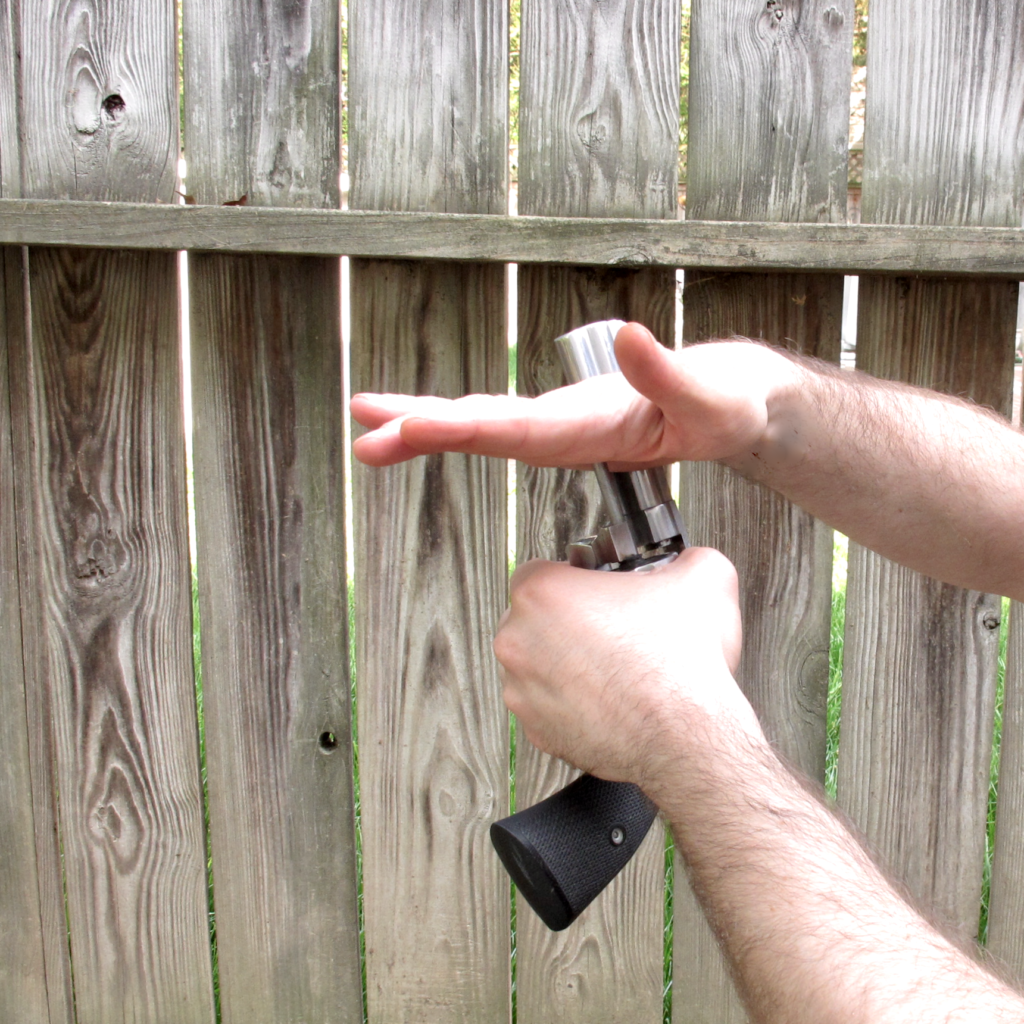

Not only does ejection need to be positively applied with a firm hand (AKA a good slap), it helps to get the gun as close as possible to vertical. This helps the brass fall straight out. Ejecting while the gun is on an incline creates conditions under which brass or a cartridge may fall under the extractor star.

Next, keeping one’s chambers clean will go a long way in helping to ensure reliable ejection of brass. Though revolvers have the mystique of ultimate reliability, they’re not maintenance-free firearms. This is especially true if you shoot a lot of .38s but carry .357 Magnum ammo. The shorter .38 cases leave carbon building up further back in the chambers where it is more likely to interfere with successful ejection.

Though it is a secondary factor, ammunition selection may also play a small role here. Nickel-plated brass is smoother than naked brass, and in my experience seems to eject a bit more smoothly. Further, .357 Magnum brass, which is 1/10th” longer and operating at higher pressure, is a little more likely to hang up than .38 Special brass. Most RevolverGuys are probably carrying .38s in their Maggies but if you’re not, it might be worth considering.

If you’re using good technique, keeping your gun clean, have tried different ammo and still have ejection issues, it might be time for a trip to the ‘smithy. Your chambers may have tool marks or other imperfections that impede successful ejection. Though there are numerous tutorials online for polishing your chambers, I would recommend leaving this task to a professional.

RevolverGuy Reviews and Ejector Rods

This knowledge will influence our policy on reviewing revolvers in the future. Rather than offer vague, subjective statements about a given gun’s ejector rod, we will provide a measurement, using the method listed here. The list of guns found in this article can be used to assess ejector rod throw relatively. This method is more accurate and fair to the firearms we review. Much more importantly, it is also more accurate and fair to our readers, who may purchase or exclude a given gun based on our reporting.

The Bottom Line

I don’t want to hamper myself with non-functioning or sub-optimal equipment. However, equipment almost always matters far less than technique, which is a product of training and practice. As I learned with the Taurus 856 (whose throw is by far the shortest of the bunch), ejector rod throw doesn’t matter nearly as much as the person using it. I didn’t have a single failure to eject in that gun, despite its incredibly short ejector rod throw. As with many things, equipment is far less important than the person using it.

Did you Learn Something From this post? Support RevolverGuy on Patreon!

†To be fair, I’m not alone. Other, far more established outlets than RevolverGuy have reviewed the King Cobra and issued similar gripes about its ejector rod.

Justin,

I have adopted a cleaning method I saw on Fortune Cookie 45’s channel. For .38 and .357 revolvers use a short rod section, a .40 caliber bronze brush and a cordless drill. This does a great job of removing carbon. With a .22 brush the ejection problems with my LCR .22 were solved.

I’m going to have to give that a try. I’ve been using .40 brushes with Hoppe’s #9 and a little elbow grease. Seems like what you brought up – and Mr. Bond expounded upon – is worth trying.

Thanks for doing a needed bit of mythbusting here. Now I understand throw instead of length. It should be intuitive but…

On the late, lamented show Car Talk, the Magliozzi brothers would wish us well by saying “May the end of your dip stick never fall off!” Now I can add, “May your rod never get bent!”

The method Jim set out has been a long standing practice of mine for ages. I put a tad bit of Brownell’s J-B bore paste on the brush and run it through the chambers with the drill on a rather low RPM. It’ll clean it right up. Also, a bit of the same J-B and a brass ‘tooth’ brush, applied to the cylinder face to clean up fouling and any lead splatter. Then I set the cylinder and yoke assembly in a jar of “Ed’s Red” and let chemistry do the rest. Wipe out the chambers with a wet patch, then spray the whole thing down with brake cleaner (the cheap stuff from Wally World does nicely), relube the yoke, and you’re good to go.

As for ejector rod throw: Justin is spot on with the training issue. The same technique can be used for about any double action revolver (except the Webleys). Watch someone like Claude Werner shooting a snub gun in a match, carefully observe his reloading technique, and you’ll see that he has like zero issues clearing .38 Special brass out of a J-Frame. He and I have the same result with J, and K frames equally – except I’m in S-L-O-W motion compared to Claude.

I carry two 327 Smith’s, one with a 5″ barrel and one with a 2″ barrel. The 2″ has as very short ejector rod throw but with good technique and clean chambers will clear .357 mag cases without a hitch. I clean both using Hoppes and Brownells bronze (never stainless steel) .357 chamber brushes which are nothing more than .35 cal rifle bore brushes. Soak the chambers of the cylinder while you clean the rest of the revolver then wet the chamber brush and run it in a cordless drill to clean the chambers. Works like a champ.

I tend to think most ejection problems have little to do with the throw of the ejector rod, and more to do with technique, grip clearance, and cleanliness (probably in that order).

Since we’re talking cleaning methods, I like to soak the chambers in Blue Wonder Gun Gel and let them sit for a while as I clean the other parts. I go back with a brush (with another dab of gun gel for good measure) and do a half-dozen passes, then run dry patches through to get things clean for inspection. I rarely need to repeat the process, but when I do, it doesn’t take much more scrubbing to get the chambers mirror bright.

When clean, run a patch with CLP through the chambers to clean/preserve.

No power tools required! ; ^ )

BTW, the gun gel does a great job breaking up the carbon rings on the front of the cylinder, too. Soak for a bit, then hit it with a copper toothbrush. Easy.

Never had much trouble with crud from .38s, since I scrub the chambers last with a brass bore brush. My wife would have a fit with the recommended method. Power tools at the kitchen counter are a no-no, even though I am the cook. I like to clean my guns there. To quote James McMurtry’s “Copper Canteen”,

“Honey, don’t you be yelling at me when I’m cleaning my gun

I’ll wash the blood off the tailgate when deer season’s done .”

Old School, I get it. The House Commander has proclaimed the kitchen table off limits to my gun hijinks as well! All it took was one little scratch . . .

I use Ye Ole cordless drill because at my age, I’m closer to dirt than the academy , and I’m rather impatient in my graying years. I want it clean like right now (translation: 20 minutes ago), so I cheat where I can. It also takes less energy on my part to clean the cylinder chambers. Gotta love the use modern chemistry and technology to defeat the residue of combusted nitrocellulose compounds.

( NOTE: make sure the copper toothbrush is thoroughly cleaned before you use it with toothpaste or your gums ‘ll bleed. )

I’ve been using toothbrushes on my guns for years, but I guess the reverse is verboten—no gun brushes for teeth? ; ^ )

Who Knew?

TOM story re: using brushes on the front of the cylinder: A coworker who was smarter than me in most areas told me it’s not necessary to get all the black off the cylinder face, and if you scrub it hard enough to do that, you could be removing microscopic amounts of steel, too; in time it could affect the function of the gun. True? I dunno, but at the time I wasn’t real conversant in the different chemical compounds that dissolved carbon, so I took his advice to heart. The fun part, once I happened on a brass or bronze brush for the purpose instead of the copper one we’d been using. It cleaned enough of the carbon off for inspection purposes, but it also left a pretty, golden color on the metal. Just because, after I finished cleaning, I gave it another brushing with the bronze brush, and left the pretty ‘gold’ on the cylinder face. Next inspection, I told Sarge it was a special finish to keep carbon from building up. He wasn’t impressed, and I almost got a day or two off for unauthorized work on the gun. Same Sergeant who got all in a dither when I put speed loaders on the belt, because they were unauthorized accessories–they weren’t issued (yet), so we weren’t allowed to have them. Had a lot of fun with him.

Back to the point, my experience has been that, nearly always, clean smooth chambers let the empties drop with no issues. I’d never really thought about the ‘length’ to ‘throw’; guess it’s not the size that counts, it’s how you use it (shame on those who take that down the wrong path). Ace

Haha! Ace, it’s a good thing Sarge never found the grenade simulators and extra box of tracers you had in your patrol bag, huh?

I’ve actually got a few guns where the B/C gap is so tight, that the cylinder will start rubbing if the face gets too dirty, so I try to keep em clean.

I knew a copper who used some Simichrome once to clean the cylinder face, and it left it all shiny and purty. Well, he couldn’t stop there, you know, so he gave the whole gun a good polishing. His Sarge (certainly related to yours, or maybe they just went to the same school) was unhappy too! “If we’d a wanted you to have a nickeled gun, we’d a issued you one!”

Great post. This has got to be one of the most commonly-repeated myths in the revolver world, and it’s been deftly taken down by clear facts. Nothing like a little sunshine to clear the stale cobwebs. Well done, Justin.

Mike, I had a supervisor when I worked in the jail who expected us to Flitz our Model 66’s to look like nickel. Just what a guy would want in his hand when searching a dark warehouse.

One of the administrative staff in the jail had a dirty weapon after qualification one time, the above Sergeant instructed her to have it clean when she came in the next day. She said her husband did the gun cleaning at her house, and he was out of town. A young deputy–we won’t worry about who–suggested she just remove the wood grips, and run it through the dishwasher. She did…. Ace

I was laughing so hard about the “husband does the gun cleaning and he’s gone” part that I almost missed the dishwasher part!

Did it have a nice lemon scent afterwards, too?

Well, I will say that, after she got laughed at about the dishwasher event, she was smart enough to ask some other people if it was true that–as that same guy told her–that putting a drop of oil on her bullets would make them fly faster and hit harder….. Ace

Most important factor is to use GRAVITY to your advantage. ALWAYS have the muzzle ELEVATED when ejecting the brass, preferably using the Ayoob Stressfire or “Spank the Baby” technique. This ensures that with a good slap that gravity will aid getting the brass out of the chambers. It is also VERY important that in doing so, anu unburned powder particles will fall out of the gun with the brass, so they cannot be deposited under the extractor. This is a particular problem with 9mm revolvers and when firing .38 Special +P or .357 from short barrels, where powder combustion may not be complete. Wheelgunners should ALWAYS carry a short, travel toothbrush to periodically sweep under the extractor and also the extractor recess in the cylinder, as it only takes ONE errant powder flake in there to cause a jam.

Good Topic.

I going to come right out and say that as a dedicated revolver guy this issue really comes down to training and technique. Getting a casing stuck under the extractor is a malfunction that you are not going to clear quickly. There’s no revolver equivalent of a “tap, rack, bang” drill for that malfunction. SO, your best option is to avoid the problem to start with.

Surprising to some, the short extractor rod of a snubnose revolver is almost completely immune to the problem. The only issue with those short rods is the need to cleanly extract the spent casings fro the cylinder. Keeping the muzzle vertical and briskly operating the ejector, will pretty much keep you out of trouble.

The long rods benefit from the same good technique but improper technique can lead to bent rods.

The force applied to operate the rod still needs to be brisk (more of a slap than a push) BUT the force applied needs to be directly in line with the travel of the rod. The easiest way to accomplish that under stress is to use the barrel of the revolver as a guide for your hand.

I’m not a huge fan of Ayoob but he does a good job of demonstrating that technique in his “stressfire” method of reloading a DA revolver.

By “popping” the rod instead of “pushing” the rod, you will get the casings to completely clear the cylinder without trapping one under the extractor. By using the barrel to guide the web of your hand, you will ensure the force applied to the rod is in-line with the rod and you will not bend the rod.

Back when the world was flat I was taught the FBI technique and frankly, it sucks. Many, many years ago I adopted a modified technique for reloading DA revolvers that is partially based on the “Stressfire” technique and it works.