While some of the nation’s oldest uniformed police departments trace their roots back to the mid-1800s, it wasn’t until the early 20th Century that the majority of American police sidearms moved from tunic pockets to openly-carried duty holsters. The earliest rigs were generally substandard in materials and design, and it wasn’t long before the search for the perfect police duty holster occupied the minds of uniformed lawmen from coast to coast.

In this series, we’ve previously chronicled the development of some of the best police duty holster designs from the first half of the 20th Century, such as the Jordan-style Border Patrol holster and the clamshell holster. Each of these landmark designs served lawmen well from their introduction, right up through the police transition to autopistols in the 1980s and 1990s, and elements of the designs continue to influence police duty holsters through the present.

Yet, as popular as the Jordan and clamshell were in 20th Century law enforcement, there was another holster design that rivaled them both. The front-opening, or “breakfront” style holster challenged the other designs and often came out on top in the holster battles of the mid-to-late-century. It’s a landmark in the development of police duty holsters–perhaps the King of them all—and a story fit for a RevolverGuy, so buckle up your Sam Browne and come along as we look at a selection of breakfronts that represent different milestones in the development of this holster design.

Breakfront roots

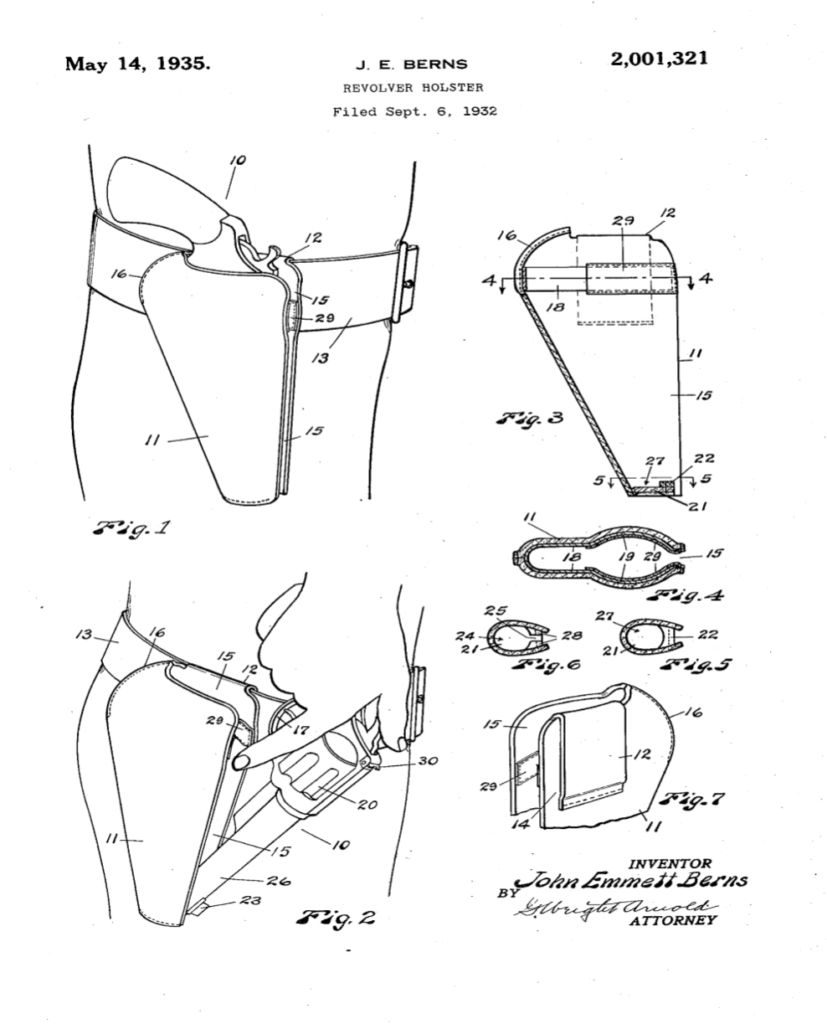

The credit for the first breakfront holster goes to Mr. John Emmett Berns, of Bremerton, Washington. In the 1930s, Berns was assigned to a naval radio station in Alaska and wanted a holster that would allow him to carry his 7.5” Colt Single Action Army revolver high enough on the hip that it would keep out of the snow while he was hunting. Berns knew that the combination of a long barrel and a high ride would make for a slow presentation from a top draw holster, so he cleverly solved the problem with a new design of his making.

In Berns’ design, the holster pouch was closed at the rear and split along the front edge. The inner and outer halves of the holster pouch were held closed along the front edge by way of an internal, flat metal, U-shaped spring that wrapped around the rear edge of the pouch. The two open legs of the spring were covered by leather and positioned to overlap the holstered gun’s cylinder. The tension of the spring legs would grip the cylinder of the gun and hold the pouch closed until the gun was forced forward against them, during the draw. Pushing the gun out the front of the holster would force the two halves apart and overcome the clamping tension that held the gun in the pouch, thereby releasing the gun.

The Berns holster incorporated a plug at the bottom of the holster to serve as a resting place for the end of the barrel. It was appropriately recessed to accept the muzzle and front sight blade configuration of the particular gun.

The Berns holster also incorporated a curved pocket at the top rear edge of the holster, which was shaped to cover the rounded trigger guard of the revolver (see #16 in the patent image, above). The curved pocket was closed, and when the gun was holstered, the pocket would cover the rear edge of the gun’s trigger guard in a way that prevented the gun from being pulled out the top of the holster. The only way to remove the gun from the Berns holster was to rock the grip of the gun forward and down, which would allow the rear of the trigger guard to clear the holster’s curved pocket, and the topstrap of the gun to force the spring clamp apart and allow the gun to come out the front.

Berns filed for a patent on his unique design on 6 September 1932, and was granted U.S. Patent number 2,001,321 on 14 May 1935. By the time the patent was received, the Berns-Martin Company of Calhoun City, Mississippi (and later, Atlanta, Georgia) had already been formed and Berns was in business with friend J.H. Martin. Berns-Martin manufactured the design (marketed as the “Speed Holster”), as well as a similar shoulder holster (the “Lightning”) that shared the spring clamp design, until 1974.

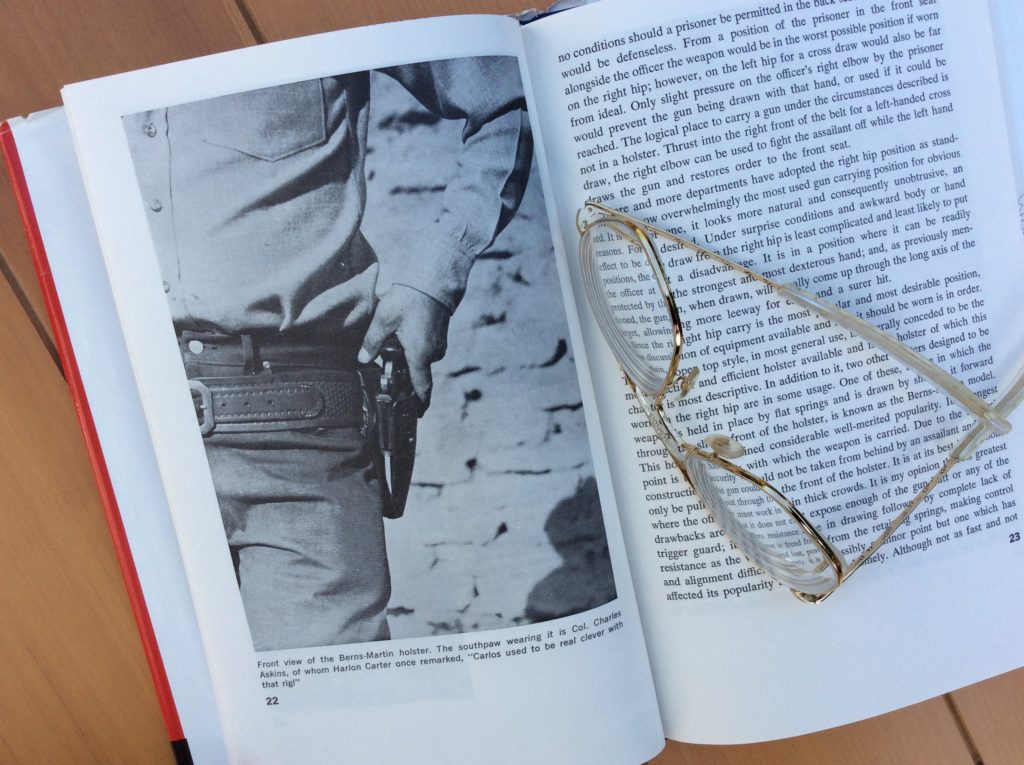

Living and working with the Berns-Martin

As previously mentioned, to draw from the Berns-Martin, the user had to force the grip of the holstered gun forward and down to clear the trigger guard pocket at the rear of the holster, and split the halves of the holster open. Because the revolver could not be removed by drawing the gun straight upwards, or even by pulling it to the rear, the Berns-Martin gave a police officer a considerable safety advantage over the traditional, top draw designs of the period. Only the clamshell holster offered as much protection from a disarm attempt (assuming an errant—or trained–finger didn’t find the release button). One negative aspect of the trigger guard pocket though, was that it could interfere with attaining a high grip on the frame, and it could also make the use of grip adapters difficult.

The forward and down movement required to clear the gun from a Berns-Martin was a uniquely different drawing motion that required practice to engrain. When the frame and cylinder of the gun cleared the spring loaded opening, the holster still maintained a grip on the barrel of the gun, which had to be overcome. When the barrel suddenly broke free of the holster’s grip, this could lead to overshooting the desired spot as the wrist flipped the muzzle upwards, into a shooting position. Legendary lawman and shooter Bill Jordan noted that this characteristic of the Berns-Martin could lead to “control and alignment issues” during the presentation, which is why he preferred the holster of his own design, but he still rated the Berns-Martin favorably in comparison to other police duty holsters.

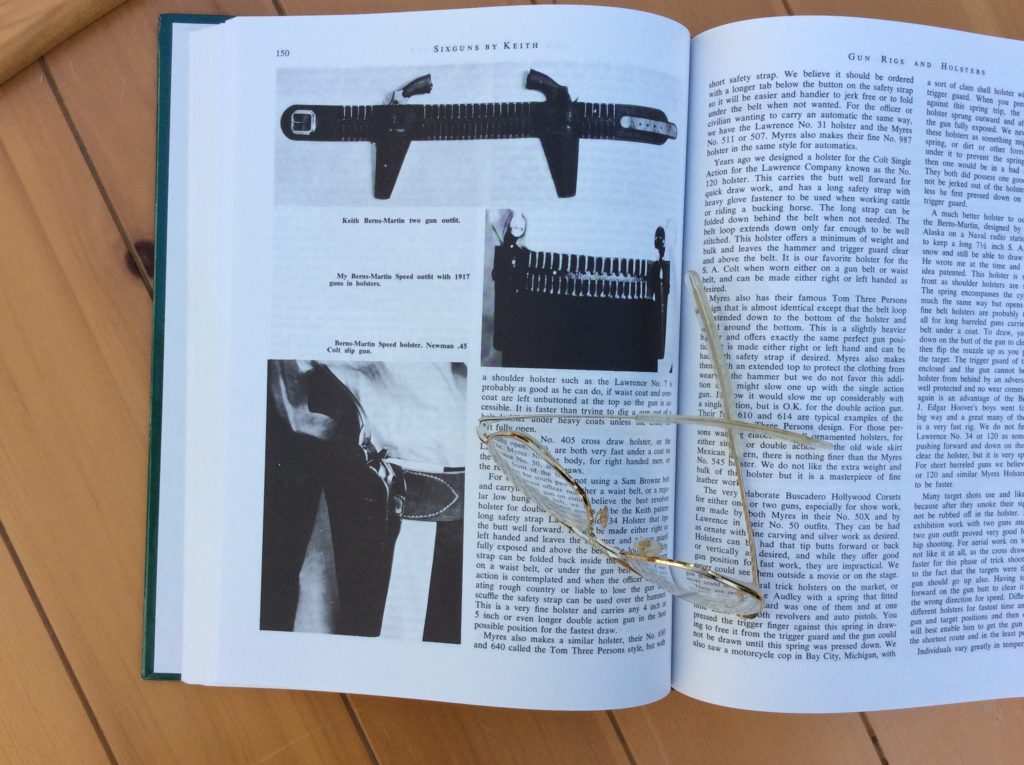

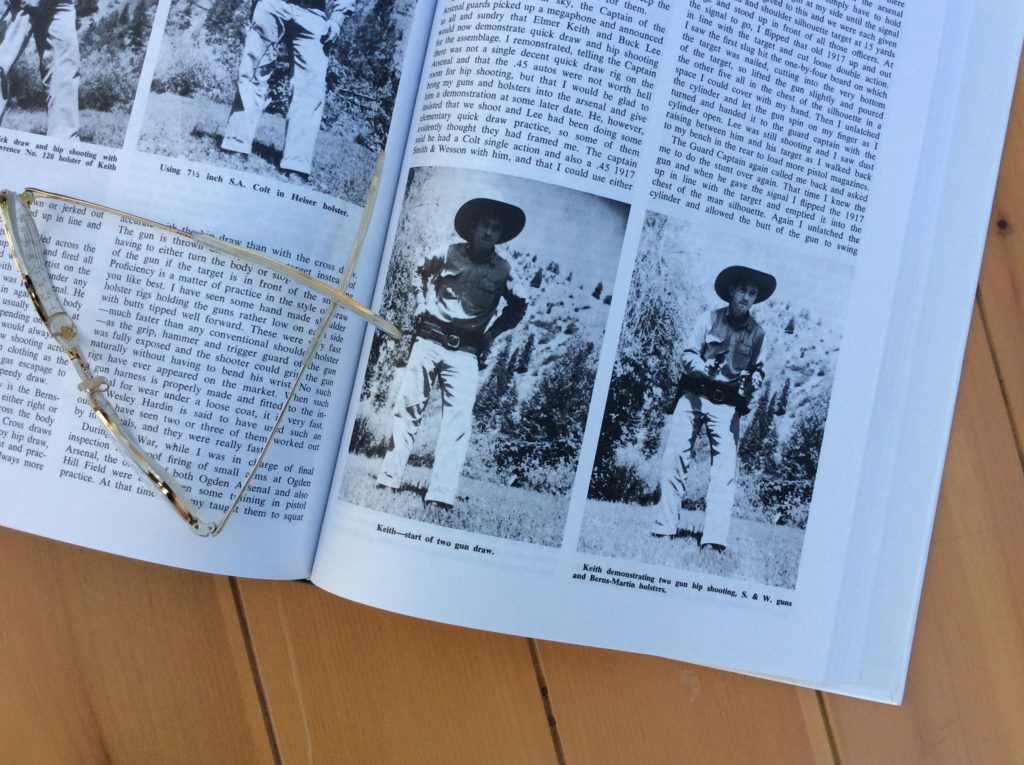

While critics argued that the Berns-Martin encouraged a “bowling” kind of draw, whose long arc slowed the presentation of the weapon on target, a practiced officer could become very fast with the rig—certainly faster than with any high ride, top draw holster, and particularly so with the long-barreled weapons favored by law enforcement at the time. Sixgun aficionado Elmer Keith declared the Berns-Martin as the “fastest holster of all for long barreled guns carried high on the waist belt,” and routinely demonstrated his fast draw and shooting prowess with Berns-Martin holsters for his favorite revolvers. There’s no doubt that the Berns-Martin draw was a unique animal, but once mastered, it could be very fast.

The rapidly opening clamshell holster may have challenged the Berns-Martin breakfront design for speed, but the Berns-Martin had an edge when it came to reholstering. To reholster the gun in the Berns-Martin, the user inserted the muzzle into the top of the holster and used it to split the halves apart as the barrel was pushed down the front seam. The muzzle was placed in the plug at the bottom of the holster, and the trigger guard and frame were rocked rearward to further lever the halves open. Once the revolver’s cylinder and top strap cleared the front edge, the holster would close and clamp around the gun, locking it in place. All of this could be accomplished positively and quickly with one hand, even while running or restraining a suspect with the other hand, giving it a clear edge over the more difficult clamshell, when it came time to put the gun away.

Competition

The Berns-Martin breakfront concept was such a clever and popular solution to the problem of carrying a long barreled revolver on a police duty belt that it inspired a host of other innovators to tweak the design and market their own samples of the breed.

The most prolific, in the early years, was Richard H. Hoyt, of El Monte, California. Hoyt had entered the leather business in 1929, and filed patents for his own breakfront holster designs in August of 1933 (U.S. Patent number 2,037,132, granted 14 April 1936) and November of 1935 (U.S. Patent number 2,109,232, granted 22 February 1938). Hoyt successfully marketed his breakfront holsters to law enforcement and the brand went on to became one of the most popular suppliers of police duty holsters.

In the late 1950s, Hoyt passed the business on to his granddaughter, Carol Lee, and her husband Woody Hershman, who later moved the business south to Costa Mesa, California, then again north, to Coupeville, Washington in the late 1970s. Hoyt Holsters, Inc. outlasted the Berns-Martin Company, building breakfront holsters in Washington until they closed in 2000.

The Hoyt breakfront differed from the Berns-Martin in several respects. To begin with, the Hoyt lacked the sewn muzzle with the plug at the bottom. The Hoyt had an open muzzle, and the two halves of the holster body were only joined along the rear seam, which allowed the spring-loaded front of the Hoyt to open with slightly less effort.

The internal spring on the Hoyt was shaped differently and went around the cylinder, instead of on top of it, as in the Berns-Martin. The inner lining of the Hoyt was also relieved to create a pocket for the cylinder to ride in, which helped to secure the gun in place and prevent its removal out the top of the holster, which was an important retention feature for uniformed officers.

However, the Hoyt model of the breakfront did not include a pocket to trap the trigger guard and prevent the gun from being drawn out the top. Instead, the Hoyt breakfronts employed a safety strap that went behind the hammer spur and was snapped closed to secure the gun in place and resist a disarm attempt from the rear.

The Hoyt safety strap was unique in that the tip had a false snap that was designed to fool an assailant into thinking it was the release point for the strap, as on a Jordan holster. However, instead of being a real snap, the false snap was actually a pivot point, which would allow the strap to rotate downward and out of the way when the thumb snap at the top of the strap was released. The thumb snap on the Hoyt was different than the thumb break patented by George Bucheimer (U.S. Patent number 2,917,213, filed 11 January 1957, and issued 15 December 1959), in that the Hoyt thumb snap was released by pushing the thumb tab outboard, instead of inboard, as on the more popular and efficient Bucheimer design.

The original Berns-Martin employed no straps, and relied only on the spring tension to retain the gun. Later models of the Berns-Martin did incorporate a strap with a snap (just above the midpoint of the leading edge of the holster) which was designed to be disengaged by the edge of the index finger as it swept forward, but it’s size and location made it better suited for administrative use, than for use on patrol. The Hoyt strap was a better design than the Berns-Martin strap, but it didn’t protect the user from a rear disarm attempt nearly as well as the trigger guard pocket of the Berns-Martin.

Whereas the Berns-Martin design was strictly produced as a high riding hip holster, Hoyt made a swivel version of their breakfront that became very popular with law enforcement officers that spent a lot of time in patrol cars with long barreled revolvers.

The Hoyt was an incredibly successful breakfront holster whose production output and tenure eclipsed that of the Berns-Martin Company.

More competition

But Hoyt wasn’t the only game in town. The Safety Speed Holster Company (of clamshell fame) also produced their own version of the breakfront holster from the 1970s through the 1990s. Safety Speed’s breakfront (designed by Paul Boren) incorporated the closed muzzle and trigger guard pocket concepts of the Berns-Martin design in a modified form, and also borrowed the internal cylinder cutouts of the Hoyt. However, Boren’s Safety Speed design improved on the earlier attempts in significant ways.

The trigger guard pocket of the Berns-Martin was an important safety feature that prevented the weapon from being drawn out the top or rear of the holster during a disarm attempt, but it also put a lot of leather material near the juncture of the rear of the trigger guard and the part of the frame where the middle finger rests. This could impede a proper, high grasp of the revolver as it sat in the holster. To improve this, the Safety Speed design incorporated a slot in the rear edge of the holster for the bottom of the trigger guard to protrude through. The slot was closed at the top with enough material to help trap the trigger guard in place, without using a surplus of material that would interfere with a proper grasp of the gun. In this manner, the Safety Speed achieved the security of the Berns-Martin, with less potential for grip interference.

The lower front edge of the Safety Speed breakfront was ever-so-slightly belled to release the muzzle with less effort, and mitigate the control issue that Jordan alluded to in describing the draw from the Berns-Martin design.

The Safety Speed improved upon the Berns-Martin and Hoyt safety straps with a design that was actuated by the trigger finger, like the Berns-Martin, but located in a much more ergonomic position. On the Safety Speed, the release snap was mounted in a position where it was easily accessible by the trigger finger as the rest of the hand grasped the butt of the gun. To release the safety strap, the straightened trigger finger hooked underneath the rear of the metal-reinforced tab, and swept it forward as part of the drawing motion, popping the snap and releasing the gun. Later models of the Safety Speed breakfront retained an identical looking safety strap, but made the snap a false one to confuse an attacker attempting to disarm the officer. In this latter version (addressed in U.S. Patent number 3,865,289, approved 11 Feb 1975), the safety strap was actually released using a Bucheimer-like thumb break that was better camouflaged than the Hoyt’s, and easier to disengage.

The Safety Speed breakfront also took advantage of a patented shank and belt loop (U.S. Patent number 3,642,183, approved 15 Feb 1972) that held the holster offset from the body to allow a uniform jacket to drape between the loop and the backside of the holster.

The features of the Safety Speed breakfront and the strength of the company’s reputation and market presence made them an important player in the breakfront battle well into the 1990s, but their efforts were eclipsed by another player that rose to dominance in the same period.

*****

(Come back for Part II next week!)

References

Adler, Dennis. John Bianchi—An American Legend 50 Years of Gunleather. Blue Book Publications. Minneapolis, MN. 2010.

Ayoob, Massad. “Safariland & Bill Rogers: The Rise of the Modern Security Holster,” American Handgunner Magazine, July-August 2016, https://americanhandgunner.com/safariland-bill-rogers/

Bianchi, John. Blue Steel & Gunleather. Beinfield Publishing. North Hollywood, CA. 1978.

Jordan, William H. No Second Place Winner. Police Bookshelf. Concord, NH. 1965.

Keith, Elmer. Sixguns By Keith. Wolfe Publishing Company. Prescott, AZ. 1955

My Hoyt is a reverse cant and the thumb break is on the inside. Made in 1980. We were issued Safety Speed but I honestly cant recall anyone in patrol using one.

Great to hear from you, Sir! That was LASD, correct?

The straps and thumb breaks were indeed changed and updated over the years. Safety Speed, Bianchi, and all the others were constantly making changes and improvements, too.

You’ll see in the photos that the high ride (late 60s vintage) has the break on the outside, but the swivel (late 80s vintage) has the break on the inside, where it’s most efficient.

LASD correct

Re My initial comment obviously a thumb break is on the inside. The reverse cant worked well in a seated position….such as inside your unit. It was also said to be much harder for someone not used to the holster to do a gun takeaway.

Mike,

This was a very interesting article. I enjoyed seeing the not only the holsters but the revolvers, uniforms and accouterments.

Thank you Sir! Part II next weekend!

FLASHBACK ALERT ! Dump Boxes . . . eeek ! Excellent article, and I did catch those sneak photos of the Python.

That Safety Speed was a transitional holster (minus the basketweave) when we went from a Muttley mix of 5″ barreled Colt and S&W .357 revolvers in Mixon Suicide Draw (x-draw) to the 4″ barrel S&W M66 in strong side draw – until the changeover a decade later to the M92 Berettas.

How did we ever make it with only 18 rounds, a 6 shot .357 Magnum, not having cages in the cars, not having body armor (until 1978), not having 250 LED lights wired up all over the patrol cars, not having onboard computers, and only having a 440 cubic inch displacement engine (with carburetors no less)!!

. . . and no GPS, just a paper map or Thomas Brothers guide!

The equipment is better these days, but I suspect most things about the job were a lot better in the Hats and Bats Era.

Well, yes and no. Not having the safety equipment that patrol cars have now makes one grateful to still be breathing. I am somewhat of jealous of all the new toys, bells and whistles, but our duty rigs weren’t so ‘busy’ back then.

We had no body cams, we carried lead saps (and used ’em as necessary), carried cans of mace that was useless for anything except shooing mosquitoes, and, the radar units that had the long ‘cone’ antenna hanging out the side window ( I want to say it was a Kustom Signals something or other) could microwave pizza if you weren’t careful (or so I was always told).

Or Tasers,Pepper spray and K9 quickly available.

Starting my Law Enforcement Career in the late 1980’s, I carried a State of the Art A.E Nelson Breakfront, Smith & Wesson Model 686 6 inch Bbl (to maximize velocity) and a Safariland quad speed loader holder, with four Safariland Comp I speed loaders. I felt then as I would now, not under armed. After that, it is was a variety of issued and personal handguns in various leather.

Today as I write, I am carrying a Smith and Wesson M&P9 and like it quite a bit. But I will always be a revolver guys at heart.

I suspect Brink’s issued me the holster that eclipsed these… I’ll have to stay tuned! I did love carrying a K frame in it, wish I still could.

I have a S&W holster that I think to be from the 1980s. I picked it up used for my S&W 64. It’s a breakfront but permits a top draw. Now I know why it is slit open in front!

This series about holsters is well written and I always learn a great deal, as I also did with the posts about speed-loaders. I’ve just started Grant Cunningham’s book about revolvers and I think a companion volume on the history of holsters and related gear is in order.

Thank you Sir! I’m glad you’ve enjoyed it so much, and think you’ll really enjoy Part II next week because we’ll cover some neat makes and models that I didn’t have time to discuss in this episode.

The holster book would be a neat project! John Bianchi set the pace with Blue Steel & Gun Leather many decades ago, but there’s been a lot of creative developments since then that are worth cataloging.

Such a great detailed article Mike! When I started in 1988, there were two guys on my department carrying 6″ Pythons in breakfront holsters and another guy with a 6″ S&W .41 Magnum in a breakfront. I started with a S&W 645 in an El Paso Saddlery high ride thumbsnap duty holster. The seat belt always scratched it and I had to polish the real leather twice a week to keep it looking good for inspection!

Thank you Steve, glad you liked it! A 6″ .41 Magnum in a breakfront would make quite an impression, indeed!

These youngsters don’t know how good they have it with plastic holsters and tenifered guns! Easy peesey. No fuss!

Except that these M&P pistols are crap… You’d have to pay me to carry one! Oh, wait, they do..

; ^ )

Thanks for a great article. I started in law enforcement as a reserve back in ’82 with a border patrol holster. It wasn’t long before I spent the money to get a breakfront for mu S&W 19. I got the Safariland that’s pictured at the opening of your article. One annoying aspect of the breakfront was the way it wore the bluing off of the sides of the barrel.

Jack, my dad’s duty gun suffered the same fate, and he had to get it reblued at one point. Come back next week for more about that Safariland holster!

You can count on that. Do I detect a mention for the Rogers holster?

“The holster book would be a neat project! John Bianchi set the pace with Blue Steel & Gun Leather many decades ago, but there’s been a lot of creative developments since then that are worth cataloging.”

Richard “RED” Nichols – most known from 20 years at Bianchi – and John Witty have a new book on the history of holsters in the 20th century. Available through Red Nichols’ web site.

The development of front break holsters by Berns-Martin, Clark, Hoyt, Boren, Bianchi, Rogers, et. al., is covered.

One surprise: Ed Clark patented a front break holster in 1932, and early B-M holsters were stamped with both patents.

(I’m a contributor to the book but have no skin in the game.)

Thank you, thank you, thank you!

I was ignorant of both Red’s website and his new book until your post. I just spent the last few minutes wiping drool off the computer after combing through the beautiful offerings on his site, and will have a copy of his wonderful looking book in the mail soon. I can’t wait to dive into it! It’s going to be a real treat and I’m sure to learn a lot from it. Will we see your byline therein?

Not a byline, but I am named in the book. Research, a few pictures, some editing. All great fun.

Neat! I look forward to seeing your fine work!

Mike, you always hit close to home! My first issued holster in 1980 was the Hoyt Hi Ride Break Front. I don’t remember if it had the inbound or outbound thumb-break, (I no longer have it) but a forceful draw could be done with it snapped! It was fast, though.

It did on a couple occasions, drop my M19 during foot pursuits! My elbow would strike the gun butt and the gun would pivot out, even when thumb-break was snapped…my poor ol’ battle scarred M19!

I quickly got one of the Swivel Hoyt’s, and this solved the dropped gun problem, but did make the draw somewhat slower. So, I got my Safety Speed Clamshell and lived happily ever after!

Great article!

Dave, thanks for sharing your experience with the Hoyt! That helps to add a lot more depth to the article, and I appreciate it. It’s always great to hear from you here!

The Hoyt didn’t clamp down very hard on the gun. That made it faster to draw from, but less secure, as you discovered!

Sharp RevolverGuy readers will remember that battle scarred Combat Magnum from the clamshell story. It earned all those marks honestly!

Mike,

The Hoyt did it’s job during a gun grab. I was in a knock down fist fight with a big guy who drove me backwards into a corner wall. He bent low during my volley of fists and I saw he had both hands on my gun butt and was pulling very forcefully towards himself. The holster/gun was nearly horizontal, muzzle rear. Sphincter several tightened up! I got him off the gun and went to my baton to end it.

The Hoyt Hi Ride held, but I sure learned a thing or two!

Glad the Hoyt did its job, Dave! Hope that guy got what was coming to him. Way to win the fight!

It sure did, that’s one reason I hold it high regard despite it’s couple drawbacks…so far nobody has invented the perfect holster.

And the guy sure got his…?

‘Atta boy!

Just wanted to tell you that I enjoyed the article. I just found my old Hoyt from the early 1980’s which I bought from their store in Washington. It is still in good shape! Mine had a slight cant that they recommended when I bought it. They measured my arm length, so my hand would hit the butt of the M19 perfectly with every draw. They were definitely artisans.

BTW, I made my way over here after reading your recent article on the 1911. My current agency ditched the Tactical Tupperware, and went with Baer UTC’s for the whole agency with the exception of the K9 officers, who carry the Baer Recon. The range scores have gone way up, and even the kids who were wonder-9 fans have been won over.

Bill, welcome aboard! We’re glad to have you here. That’s neat info about the ordering process from Hoyt–sure sounds like it was a semi-custom operation. I heartily approve of the M19 selection!

Glad you liked the 1911 article too. For those who are wondering, it’s here at PoliceOne:

https://www.policeone.com/police-products/firearms/articles/481877006-The-case-for-the-1911/

The Baer UTC would make one heck of a duty gun! Those are some lucky officers. It’s interesting that the agency moved away from plastic and towards the 1911 . . . new chief?

I retired in 1995, so my memory is hazy about which breakfront I owned. I do remember twice I apparently had forgotten to snap the safety strap after a car stop when I had drawn my 6″ 41 S&W, then while on patrol the seat had pushed the revolver forward slightly, enough though, when I was in a foot chase shortly there after had had to follow the suspect over a fence, when I landed, the revolver popped out of the holster. I recovered it, but it could have been a bad scene. The almost identical thing happened months later and I changed the break front shortly there after. Yes it was operator error on my part. But I still considered it a potential hazardous situation I wasn’t willing to allow to continue. It sounds like I was the only one that had that happen to, I’m glad for that.

God bless & thanks for the article.

I bought my holster right-hand 357 Smith k frame side arm. In 1984, as a city, county, and a state police officer and gun range instructor I found over and over it held my weapon secure in foot prosuit, hand to hand, car wrecks and floods,

It gave me a draw that cut movement and lifesaver time. It takes a little longer to reholster but that’s not when it matters.

I’m getting one for my granddaughter and grandson that’s are officers though most department now carry simiautomatics , not having to draw your weapon up and out, is a game changer and Id rather that Milla sect these holster provide on the side of those who serve our community.

Gavin, I think AE Nelson would be your first place to look for a breakfront holster, these days. Their holster is similar to the old Hoyts.