Sometimes I’m a little slow in catching on . . .

When the Ruger LCR revolver debuted in 2009, I quickly dismissed it. It’s radical looks were a turnoff, and although I had grown to accept the use of polymers in self-chuckers, I was not ready to see them incorporated into revolvers yet.

Let’s face it. I’m a conservative guy in every sense of the word, and the LCR hit all the wrong keys for me. To a guy who was raised on blue steel and wood, with graceful lines and checkering in all the right places, the LCR looked all wrong. The frame was bolted together like a piece of industrial equipment, the finish was three different shades of matte black, and the cylinder looked like it went halfway down the garbage disposal before it was fished out. The trigger guard’s lines didn’t look “right” to my eyes, and some guy with no aesthetic taste decided to write the first half of the owner’s manual on the side of the barrel.

Yuck. Outside of the Nagant, I never thought I’d see a wheelgun that made a Webley look elegant, but yet, here it was. The scribes in the gun rags told me the styling was “space age” and “modern,” but I just thought it was homely. If this was the future of revolvers, you could leave me behind in the past, thank you very much. I’ll be over here with the polished steel, walnut, and dust in the corner . . .

Beauty is more than skin deep

The thing is though, the ugly little duckling started to grow on me. The gun began to work its charm the first time I had the chance to shoot it. Without benefit of a warm up on paper, I found myself trotting through a Donga-like course in the desert with an LCR in my hand and a pocketful of speedloaders, trying to hit scattered steel that was partly hidden in the dunes and brush. Although I struggled at times to find the right elevation with the unfamiliar gun and ammo, I was immediately impressed by the smooth trigger, the recoil-absorbing grips, and the improved sight picture. I walked away from the experience grudgingly admitting that the gun actually shot better than my beloved (and simultaneously hated) Centennial J-Frames.

After that maiden voyage with the plastic fantastic, I no longer turned the pages on reviews of the gun. My appreciation for it slowly grew, as I read the positive things that people had to say about its ergonomics and performance. When some friends—whose opinions and experience I greatly respected—gave the gun solid reviews and traded their carry Smiths for one, it really gave me pause.

Maybe I had been to hasty in my rejection of this gun? I still thought it looked unattractive, but performance generates its own kind of beauty, and there was no escaping the fact this gun could shoot.

As my respect for the gun’s capabilities grew, my resistance to the gun’s appearance faded away. I don’t know if the initial shock effect just wore off and I got used to it, or if I actually started to like the edgy look a little bit, but the gun started to have a rough charm of its own. It wasn’t pretty or graceful, but it did exude a certain, pug-nosed, utilitarian, aggressiveness that befit its role as a self defense gun. A few more range trips with the gun sealed the deal for me. Radical looking or not, this snubby was a shooter, and it deserved more of my attention.

With this, I took a closer look at what makes the LCR tick, and discovered along the way that the LCR represents an important step in the development of the revolver. So, I’d like to go inside this gun with the RevolverGuy audience and share what I’ve learned about it’s unique design.

Market interrupter

We’ll start by going back a decade, to the birth of the gun.

The snubby revolver market had grown a little stale by the time the LCR appeared in 2009. Although other makes were available, the lion’s share of the snubby revolver market was owned by Smith & Wesson, with Ruger and Taurus bringing up the rear (1.) Colt’s had long ago abandoned the commercial market, turning its back on it like a panicked groom leaving his bride behind at the altar, and their excellent D-Frame snubs were already being mourned by RevolverGuys and commanding inflated prices.

Although the catalog was diverse, the Smith & Wesson line looked much as it did a decade or two before. After the introduction of the popular Centennial models in 1989 (Model 640) and 1990 (Model 642), Smith & Wesson stretched the J-Frame to accommodate the .357 Magnum in 1996. Although S&W had been creative and kept things fresh with the use of new materials like Titanium (1998) and Scandium (2001) in their snubs, the basic Centennial design was now almost two decades old, and the external hammer J-Frames were senior citizens, at more than six decades of age. Sadly, the popular K-Frame snubbies had disappeared, with the termination of the Model 19 in 1999, and Model 66 in 2004.

Taurus was still occupied cranking out several versions of their popular Model 85 snubby, but the quality of these economy guns didn’t approach the guns from Springfield, and they weren’t seen as equal competitors. Instead, the Brazilian guns were viewed as budget substitutes for folks who didn’t have the money to spend (or didn’t want to pay the premium) on the Smith & Wessons.

For their part, Ruger had but one snub design in the catalog—the chunky SP101 which had been introduced in 1988 as a .38 Special. The gun had its roots in the 1985 launch of the Medium-Large frame GP100, and was essentially a fixed sight, 5-shot version of that gun with a smaller frame and barrel. The “mini-GP” was typical Ruger though, in that it was overbuilt for the job—so much so, that gunsmiths like Rick Devoid were successfully boring out the cylinders to handle 125 grain .357 Magnums (the heavier weights were too long for the .38 Special-length cylinder). The “Pocket Rockets” (H/T Mike Izumi) handled the powerful cartridge with aplomb, leading Mas Ayoob to pressure Bill Ruger to offer the gun in the Magnum chambering as a factory item. Ruger Sr. eventually gave in, and the gun showed up with a longer, .357-length cylinder in 1991.

So, the SP101 was Ruger’s “small” gun, but at 26 ounces and 7.2 inches overall length, it was still a good chunk of steel, and was still appreciably larger than the snub offerings from S&W. Ruger needed a trim and lightweight snub to break Smith & Wesson’s monopoly on the lower weight class, and the LCR would be it.

Design Goals

Ruger’s chief revolver engineer, Joe Zajk, led the effort to design the LCR, and from the start it was obvious that the gun would be different than anything Ruger had ever made before.

The Ruger LCR team worked with several main objectives in mind:

Keep the gun light. They didn’t need another SP101-type brute;

Give it a good trigger. The overriding goal was to make this gun easier to shoot than others of the breed, and that would start with designing an improved trigger;

Make it easy to produce. It’s a hallmark of Ruger’s philosophy to design guns that are suited for modern day, mass production methods, which don’t involve a lot of hand fitting and detail work;

Keep the gun affordable. Also a Ruger hallmark, the gun had to be economical and provide a competitive value.

It was a daunting task for the team, but Ruger was up to the challenge.

Materials

To accomplish these objectives, Joe Zajk started with a look at the materials involved. Since the cylinder and barrel required the use of steel to contain pressures, the only real place to consider different materials was in the frame.

Aluminum alloys had been successfully used by S&W to save weight in their Airweight line of snubs for many years, but Zajk’s team knew that they couldn’t achieve their desired weight reduction goals with that material, and it would still require some machining (and thus, expense) to produce an aluminum frame. Instead, they looked to use polymer, which would be both cheaper and lighter than metal, and would simplify manufacturing, since complex, intricate shapes could easily be produced straight from a mold.

The difficulty with polymer was that it wasn’t strong enough for the part of the frame surrounding the cylinder. Both the barrel and cylinder needed a stronger material to attach to—one that could withstand the recoil forces and the hot jet of high pressure/temperature gas that leaked out from the barrel-cylinder gap. Polymer wouldn’t stand up, and an aluminum alloy was the best, lightweight substitute for steel, here.

Some traditional revolver designs incorporated a separate grip frame that was mounted to the upper frame that held the cylinder, and it was possible to use polymer in this application to shed weight. However, Ruger knew that the savings would be minimal compared to an aluminum part, because the grip portion was such a small piece of the overall design. As a result, a more radical approach was required to take advantage of their chosen material.

Frame design

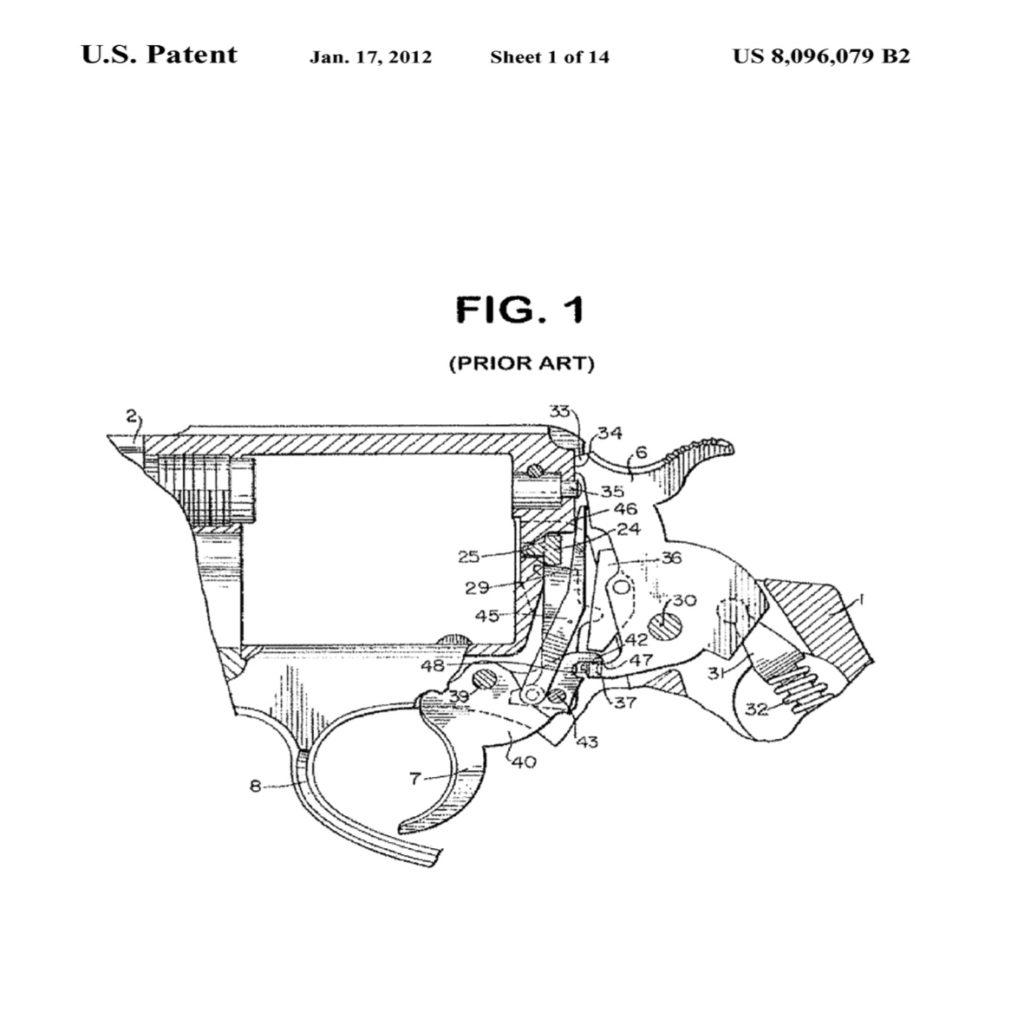

In previous revolver designs from Ruger and others, the frame was designed to house the hammer and its associated action parts. This meant the metal frame had to be extended past the rear of the cylinder to provide the space to mount these parts. Likewise, the frame was extended below the cylinder to house the trigger lock work and hold it in alignment with the hammer and cylinder.

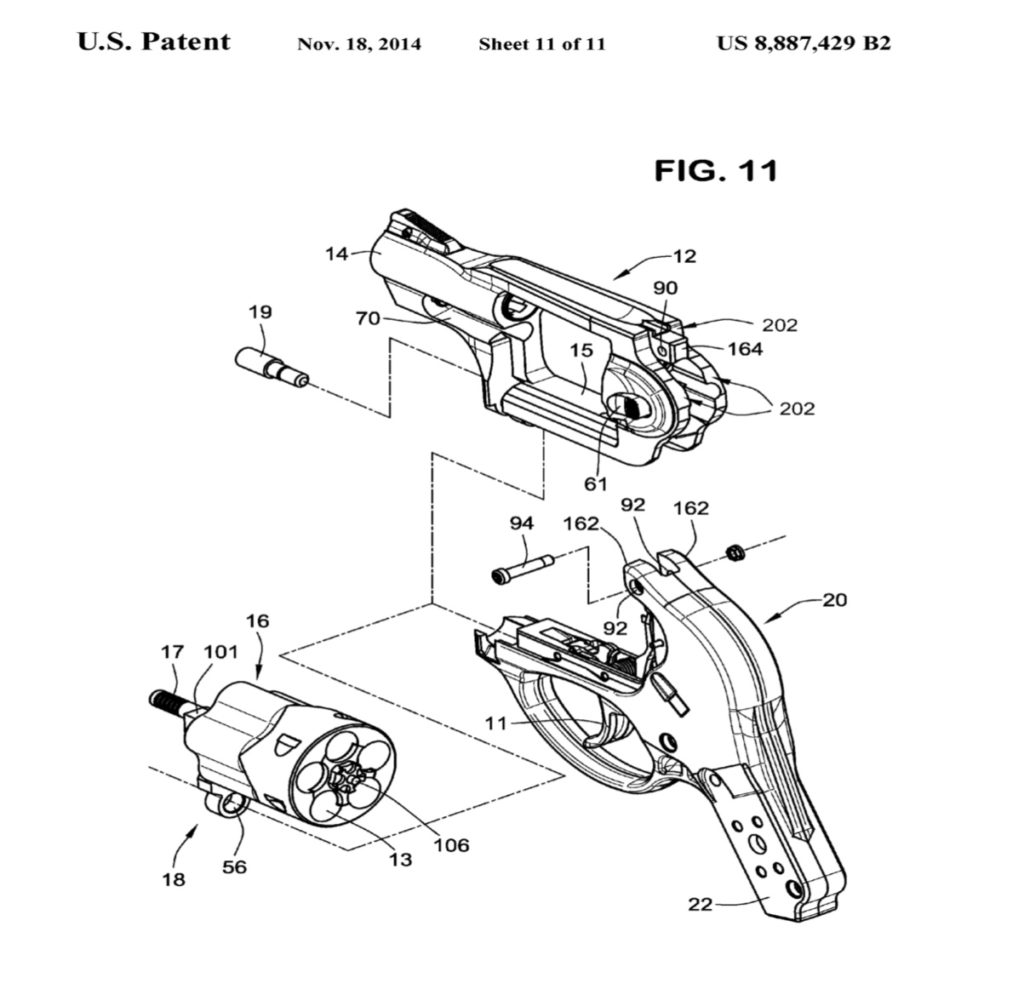

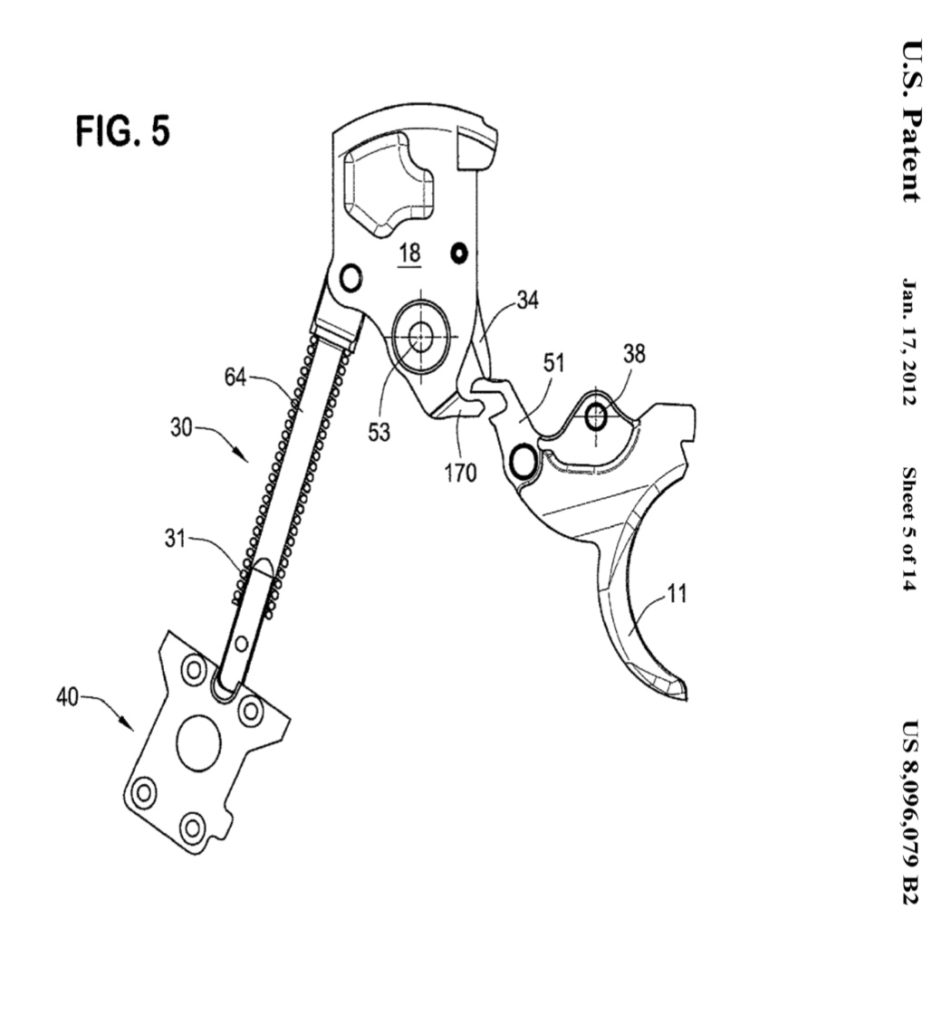

Zajk reasoned that extending the metal frame was unnecessary to house these action parts, and that a polymer structure could do it and save weight. A reduced size, aluminum alloy frame could support the cylinder and barrel, without being larger than necessary. This upper frame would provide the strength required to handle gas pressures and recoil forces, and resist flame cutting. Meanwhile, an increased size, polymer grip frame—the so-called “fire control unit”—could host the entirety of the trigger and hammer assemblies in one housing.

Ruger had been clever in designing its former Security/Service/Speed-Six line of revolvers to incorporate a trigger assembly that was easily removable as a single package from the metal frame, but the hammer assembly remained a separate unit, which was also pinned to the frame. The same method of design had been incorporated into the metal GP100 and SP101 frames as well, but Ruger had never built a revolver where both the trigger and hammer assemblies could be removed from the frame as a single, combined unit. Actually, nobody had.

Besides the potential weight savings, there were other advantages to the polymer fire control design. The action parts could be held in close and consistent alignment by placing them into the same, rigid structure, which reduced minor fitting requirements during assembly and reduced some inherent slop in the marriage between the frame and the removable assemblies. This would both make the gun easier to produce, and increase the potential for an improved trigger action, due to better tolerances and fit.

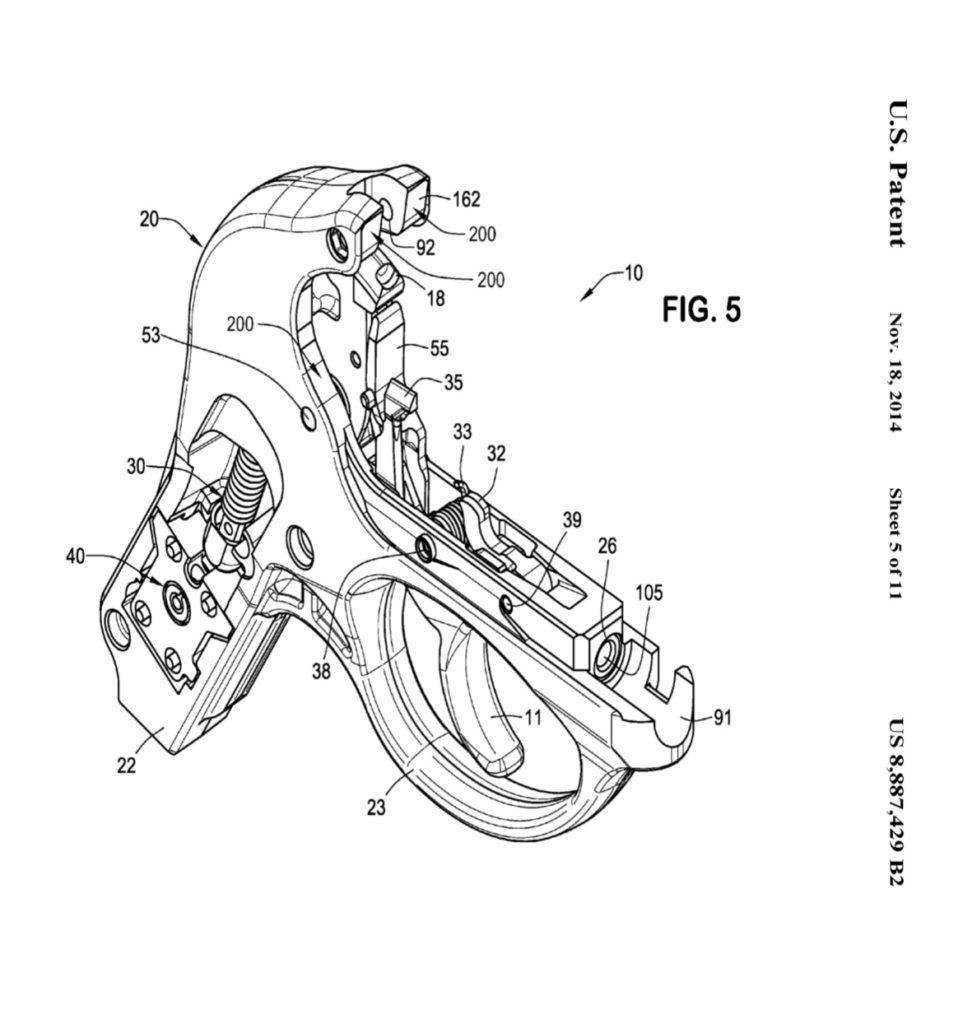

The modular frame concept, with a lower, polymer fire control unit that incorporated all the action parts in one assembly, was so novel that Zajk and Ruger (as the assignee) were granted a patent for it. (2.) Part of the patent included Ruger’s strategic use of a metal insert in the polymer frame, and their clever use of rounded bearing surfaces between the metal and polymer frames to accommodate the recoil forces generated during firing. It’s simple to slap a polymer lower onto an aluminum upper, but if it’s not done carefully, the recoil can damage the polymer lower along stress risers (as some AR-15 lower builders have discovered). Ruger avoided this by pinning an aluminum block into the fire control unit near the yoke, which provided a metal-to- metal contact between upper and lower. Additionally, the rounded rear profile of the aluminum upper helped to distribute recoil forces without creating damaging stress risers in the polymer frame behind it, ensuring the durability of the lightweight design.

Barrel design

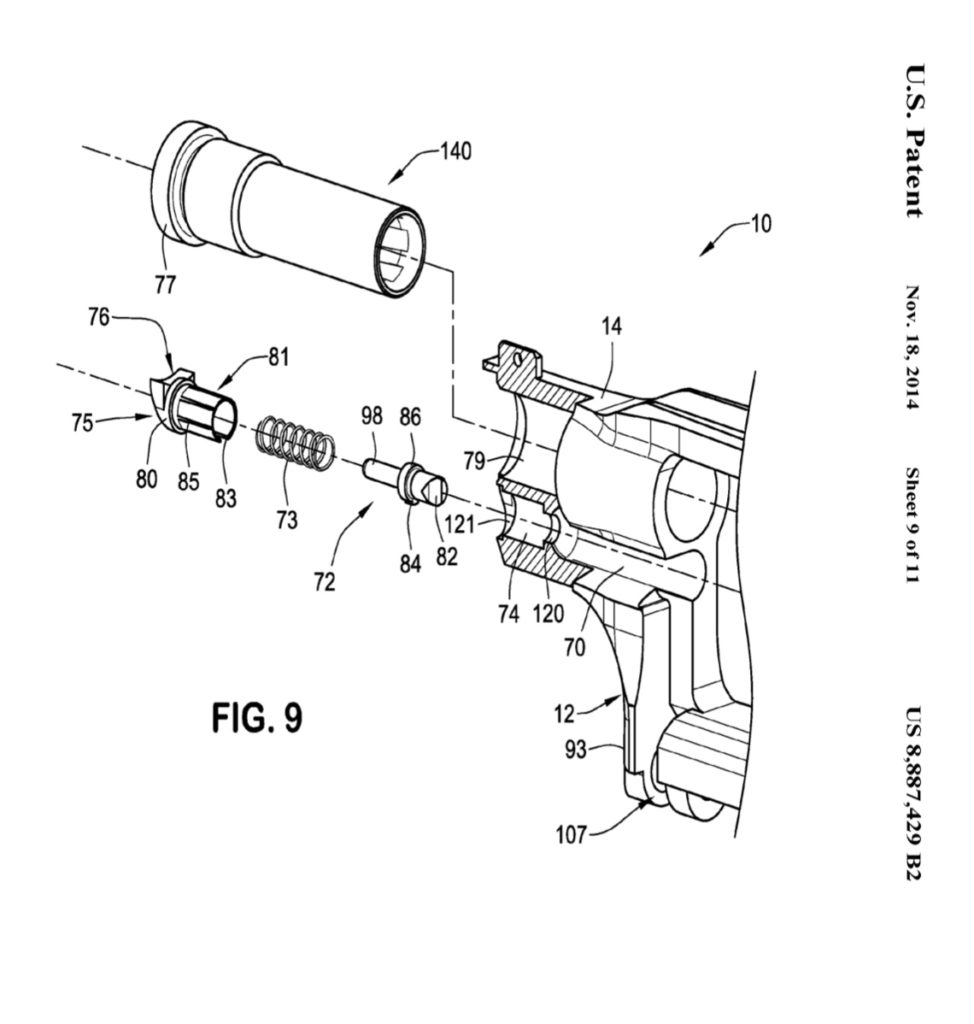

Ruger accomplished a similar tradeoff between strength and weight in its barrel design. Unlike the SP101, in which the bore is drilled through a solid piece of stainless steel, the LCR’s barrel is constructed of multiple pieces. A low profile, stainless steel barrel liner is fitted to the frame to provide the necessary strength in this high stress application, but it’s surrounded by a full profile aluminum shroud, which is part of the upper cylinder frame. The lightweight shroud houses both the ejector rod lockup components and the front sight assembly, and saves considerable weight over a one piece, steel barrel.

As in the S&W design, the tip of the LCR’s ejector rod is locked with a spring-loaded plunger in the barrel shroud, but the Ruger advances on the standard J-Frame sights by pinning a removable blade into place, instead of machining it as part of the barrel. This allows the user to replace the front sight with a different height or design, to suit his needs. The OEM LCR sight is much improved over the typical J-Frame blade (it’s wider, with a white insert), but it’s nice to have the option to change it if desired.

Gun diet

While the polymer fire control unit, aluminum upper frame, and two-piece barrel all combine to save weight on the LCR, they’re not the only ways that Ruger saved ounces on the gun.

The backside of the trigger face, for example, was hollowed out to save some weight, but you’d have to look for it to see it. What’s more noticeable is the radical relief of the cylinder’s diameter.

The forward portion of the cylinder has been reduced to the minimum necessary to contain pressures, while the rear portion (particularly the area where the bolt notches are) remains at full diameter. This gives the revolver an unusual appearance that can trigger strong reactions from potential consumers. I definitely fell into the camp that disliked the look early on, but as my appreciation for the gun grew, I found it less objectionable. Besides the advantage of weight savings, the smaller cross section probably aids a bit in holstering, by eliminating a large corner to catch on the mouth of the holster.

Trigger tech

I mentioned previously that the modular frame design, which keeps trigger and hammer parts together in the polymer fire control unit, is protected by a patent. It’s not the only patent earned by Ruger for the LCR, however, and for my money, it’s not the most significant one, either.

The polymer fire control unit is a notable achievement. It shaves nearly a full ounce off the weight of the aluminum-framed, S&W Airweight 642, making the LCR lighter to carry. More importantly, it costs Ruger less to make the gun, giving them a competitive lightweight with a larger profit margin. However, the attribute which attracted me most to the gun was not it’s feathery weight, but the quality of its action, and that’s where a second patent comes in.

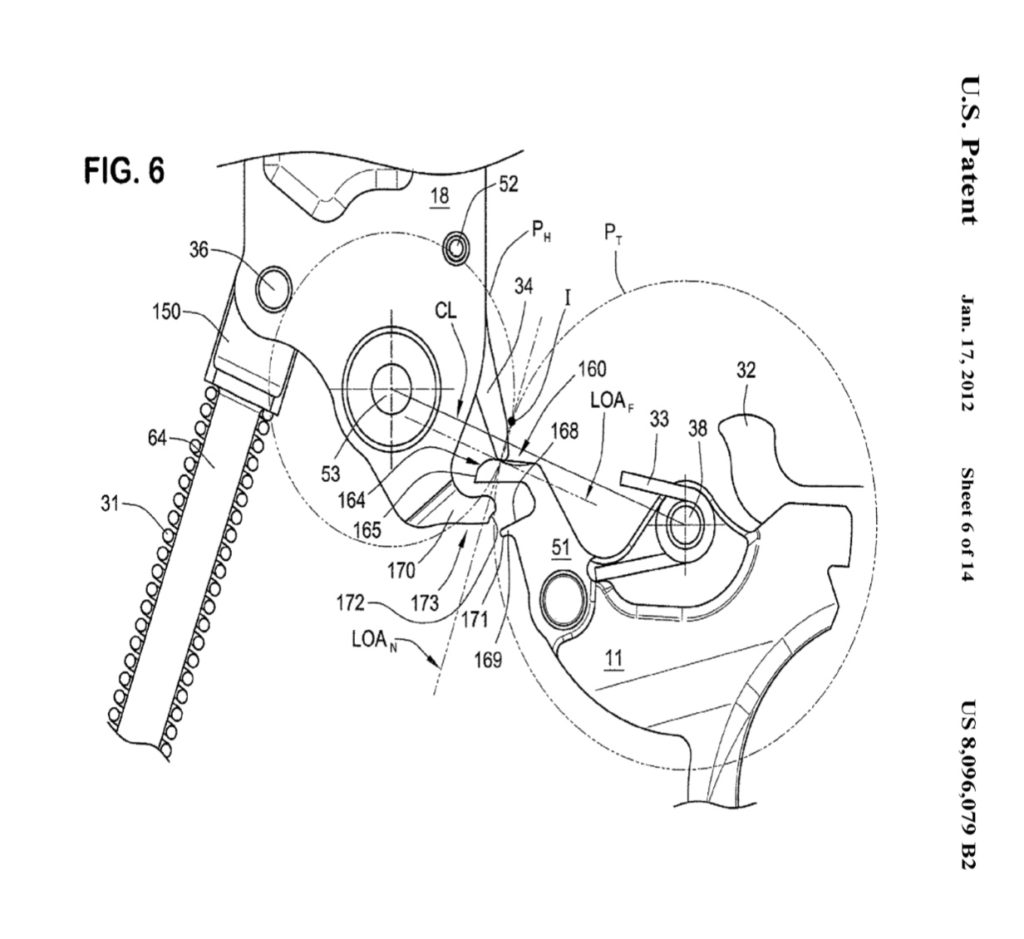

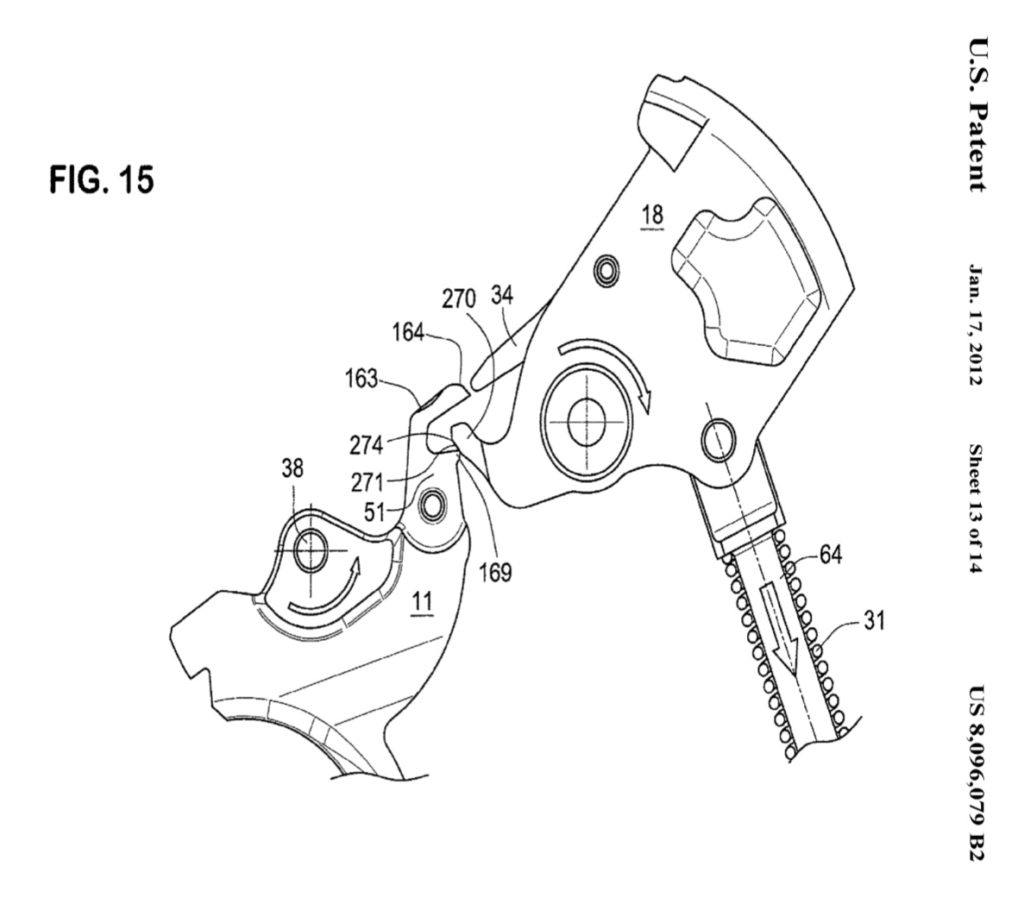

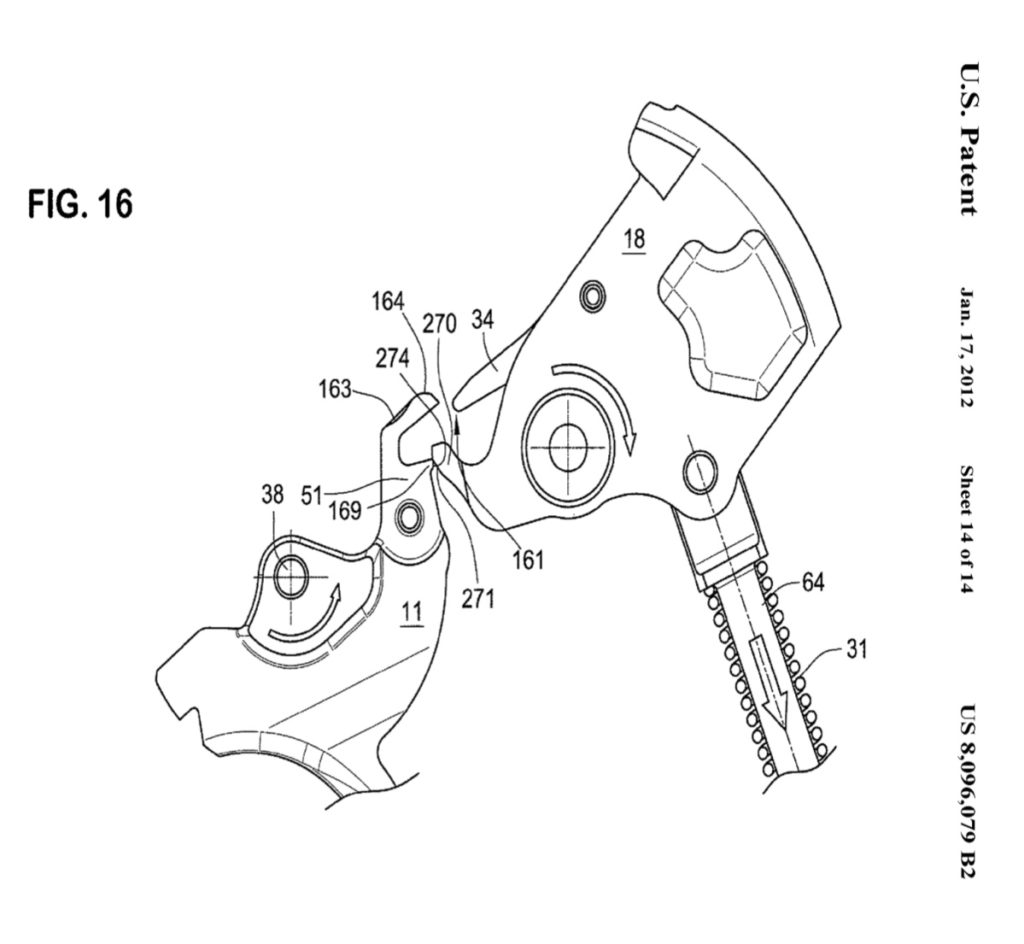

In S&W-like double action designs, an extension on the trigger acts on a lever attached to the hammer that Ruger calls the “hammer dog” (and S&W just calls the “sear”). Movement of the hammer dog by the trigger extension starts the hammer back against mainspring tension, and rotates the hammer into a position where it can be handed off to the trigger directly. Further movement of the trigger continues to rotate the hammer until the double action sear trips, releasing the hammer to fly forward.

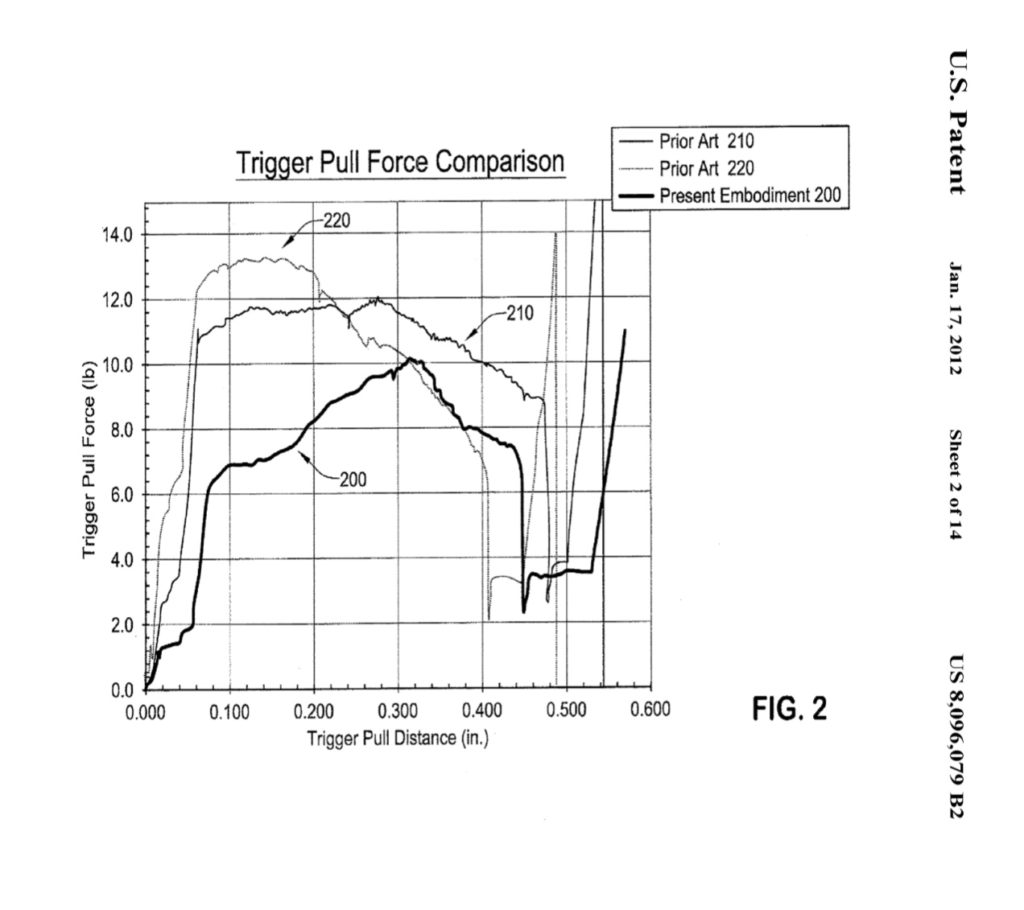

The system has worked well for over a century, but due to the springs and geometry involved, there’s a relatively heavy resistance (from trigger return spring, mainspring, and friction) to start the hammer dog moving and get the hammer rotating. The required trigger force peaks very quickly over a short distance of trigger travel, and can be uneven due to friction as the parts slide against each other.

If you graphed the movement of the trigger versus trigger pull force, you’d see that in the Smith & Wesson-type action, the trigger force continuously increases until a peak is achieved, then levels off for a while. This level off is where some shooters have learned to pause, and “stage” the trigger.

As the trigger pull continues, the weight of pull increases again for the second stage, then decreases a bit (like hitting a “speed bump” in the road), just before sear release. Unfortunately, fighting the rapidly increasing weight of pull tends to encourage trigger control issues, and the inter-stage “speed bump” near the end of the Smith’s pull does the same, often leading to a trigger jerk right before sear release.

Zajk saw room for improvement here. He reasoned that if he could make the trigger pull more linear, and reduce the force required to trip the sear, it would make the gun easier to shoot and it would be less disruptive to the alignment of the gun on target. Instead of a trigger that ran in fits and starts, and peaked at a high pull weight, Zajk wanted a trigger that acted more consistently, and didn’t require as much muscle to move it.

He accomplished the goal with some subtle changes to the action’s geometry. Without trying to stretch the limits of my engineering knowledge, I’ll try to explain.

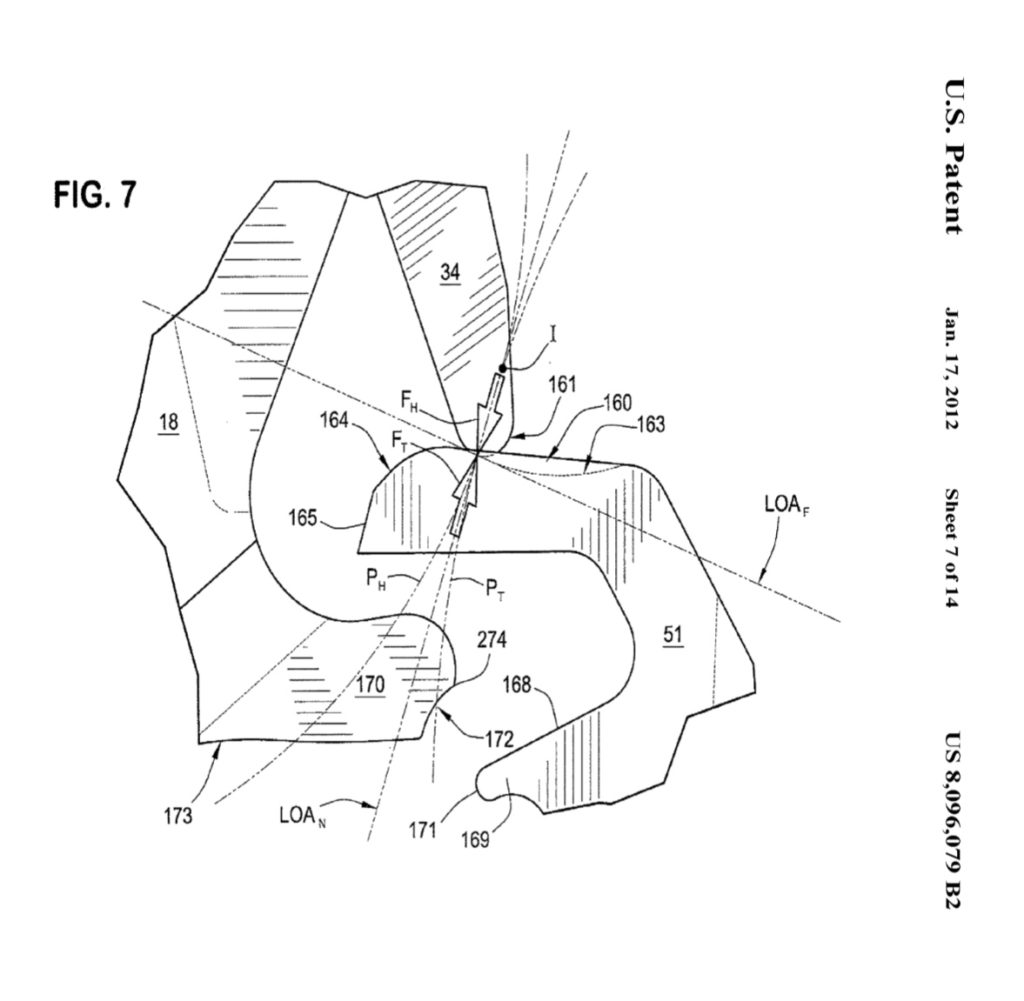

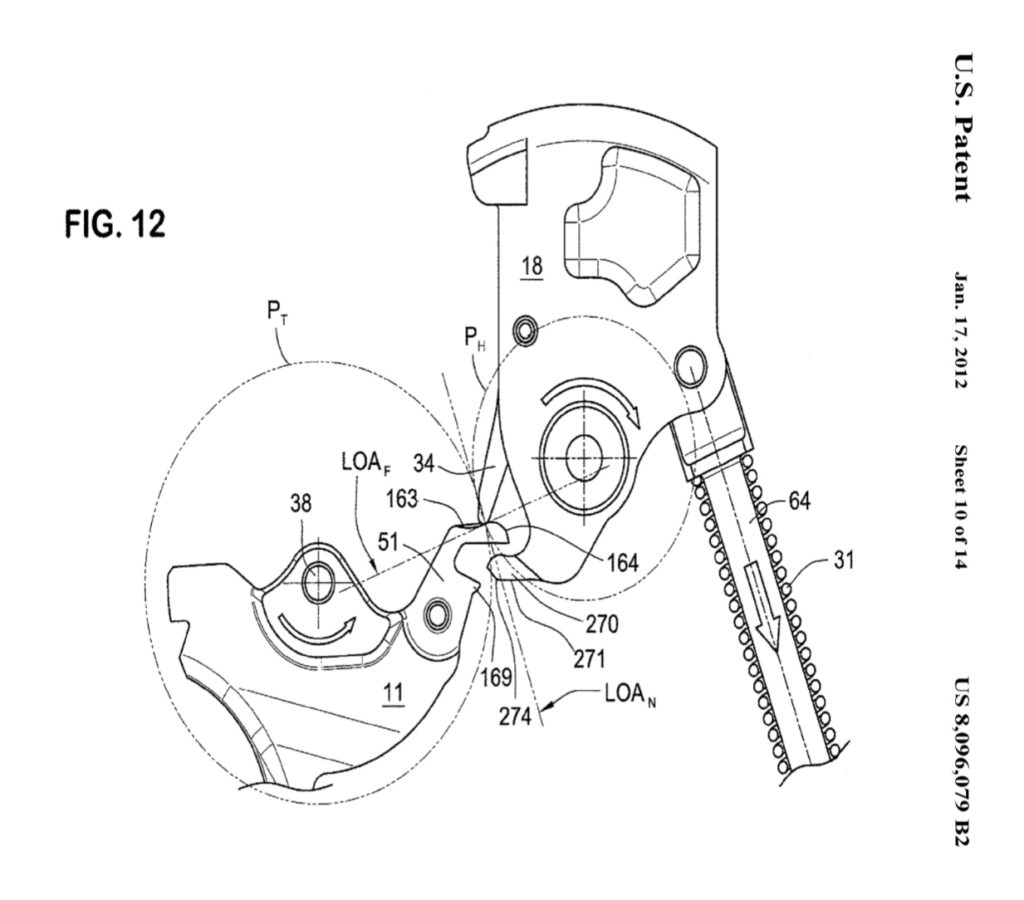

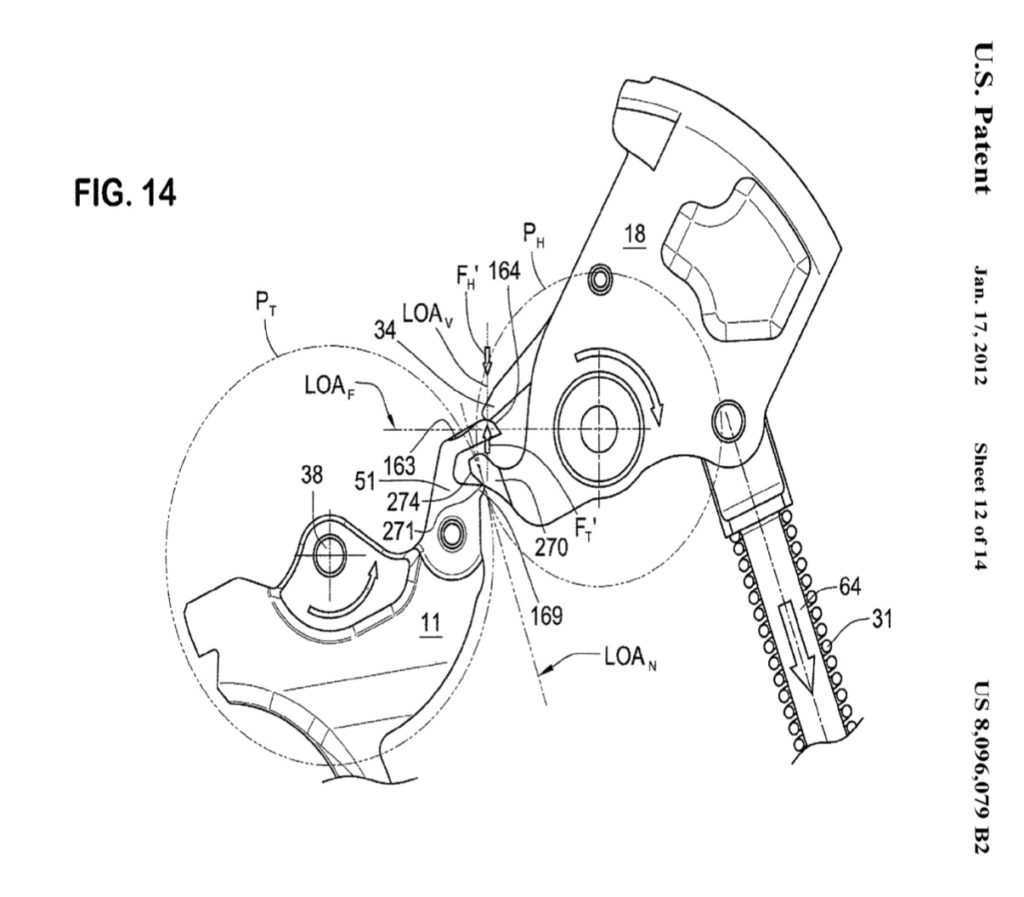

Zajk modified the surfaces on the trigger extension, hammer dog, and hammer in a way that maximized the leverage applied by the trigger. The mating surfaces were curved (some concave, some convex), and the force generated by the rotation of the trigger was applied to the hammer dog and hammer more evenly (Zajk said, “tangentially”), where they met. This application of tangential force maximized the leverage in the system and reduced the friction between moving parts.

Imagine trying to pass through a large, heavy revolving door in a hotel lobby. If you push on the door in the center, close to the hub, it will require much more force to rotate the door than if you pushed at the outer edge. By applying your force at the outside edge of the door’s arc, you are maximizing your mechanical advantage. Zajk’s team essentially modified their trigger and hammer parts to interact in a similar fashion, instead of “pushing on the center of the door” like other makers had before.

In the LCR, initial movement of the trigger causes the concave portion of the trigger extension to bear on the hammer dog, and start it pivoting, which in turn starts the hammer rotating. As the trigger pull is continued, the convex portion of the trigger extension bears on the hammer dog, and continues hammer rotation to the point where another shelf on the trigger begins to bear on the convex lower portion of the hammer. Further trigger rotation brings the hammer to its full cock position and releases it when the sear trips.

The modified geometry maximizes mechanical advantage, which requires a lower input force to make everything work (Factory specs for the centerfire guns call for an 8 – 14 pound trigger pull, 13 – 17 pounds for the .22LR, and 14 – 18 pounds for the .22 Magnum, but you can expect to hover around the low end of those ranges). It also reduces the stall or binding that happens at the beginning of a trigger pull on other designs, which means that the shooter doesn’t have to rapidly apply a large amount of force (read: “jerk the trigger”) to break things loose and get things started in motion. The rolling, curved surfaces create less friction than found in other designs, which makes the pull more consistent, or “linear,” and reduces the amount of force required to keep things moving. Additionally, the curved surfaces eliminate the “speed bump” after the first stage, near the end of some trigger pulls, as the hammer is handed off to the trigger shelf.

In sum, the modifications incorporated by Zajk made the trigger easier to pull, more consistent, and didn’t encourage yanking or jerking the trigger, particularly at the end of the stroke.

It’s worth noting that Zajk wasn’t the first to incorporate modifications like these. Gunsmiths had been playing with subtle changes to the four cam surfaces in S&W-type actions for many years, in pursuit of improved trigger pulls. The real genius of Zajk’s contribution, and the basis for the patent he was awarded, is that his modifications made it possible to get an improved trigger on a mass production gun. The previous attempts by custom ‘smiths arguably resulted in better trigger pulls than the LCR’s, but they required a lot of individual attention from a skilled craftsman. In contrast, the LCR got close to those actions straight from the box, without the need for careful fitting and polishing during assembly. This allowed Ruger to deliver an improved product at a low cost, which is the goal of any corporation, but an essential element of Ruger’s corporate identity.

The only criticism I have of the trigger is that it suffers from a weak, or sluggish return compared to a S&W or Colt’s action, or even to the company’s own SP101/GP100. In the S&W design, a hearty rebound slide spring resets the trigger after sear release, but in the LCR, a small mousetrap spring returns the trigger, and it’s just not powerful enough to do it with the same authority. Of course, this is part of why the LCR’s pull weight is lower than that of the Smith’s. There’s no free lunch in physics.

Quite a turnaround

I didn’t get off to a good start with the LCR. The radical cosmetics were a turnoff to my conservative tastes and I foolishly didn’t look past them to see the amazing design that lurked behind the scenes.

It wasn’t until I put rounds downrange through the gun that I recognized there was something I had missed about the LCR. The excellent, stock trigger was hard to ignore, and it turned out to be the gateway to a better understanding of the genius that went into the design of this featherweight snub.

The LCR is celebrating it’s 10th anniversary this year, and I missed out on most of the first decade with this gun, but I’m making up for it now. A brace of LCRs reside in my stable and they’re getting a good workout. The more I work with these guns, the more impressed I am with them.

I still have to admit a slight bias against the cosmetics, but they’re looking more and more handsome to me all the time. In any case, the looks won’t keep me from enjoying these wonderful snubbies, and appreciating all they are capable of doing. Standby for a more detailed field report on the LCR in these pages, soon.

*****

Endnotes

(1.) Per the BATFE, Smith & Wesson manufactured 221,895 revolvers in 2009 and Ruger manufactured 163,825. The BATFE didn’t report imports by manufacturer or type, but the sum of Brazilian manufacturers (including Rossi, Taurus, and possibly others) were responsible for sending 526,011 handguns to our shores in 2010. It’s a safe bet that the majority of those were Taurus autopistols, particularly their popular clones of the Beretta 92. It’s highly doubtful that Taurus revolver sales exceeded the Ruger total;

(2.) On the .357 Magnum and 9mm guns that followed, the fire control unit was made of stainless steel, to handle the increased pressures and forces developed by those cartridges. The added weight helps to mitigate the effects of recoil, as well.

Liked it? Support RevolverGuy on Patreon!

Did you enjoy this article? Mike spent a month researching and writing this masterpiece about the design of the LCR. There aren’t many sites that offer content like this. Please let us know what you think it’s worth to get articles like these. Without your support efforts like these are simply unsustainable. We appreciate it!

It has such a pleasant trigger. Now I know why, and the return on the .357 did not bother me. Very good breakdown of how it worked.

Last year I picked this gun as choice #3: great trigger but too light for even .38 +p, which is my carry ammo. The DAO Sp101 came in at #2 as gritty, with a heavy trigger but right heft for follow-up shots. The Kimber I bought won, with the right weight for accurate follow up and the best trigger of all. The alloy J Frames were just awful in all respects, which saddened me as I love my K Frame 64. Could not find an all-steel 649 to test…

Any of these snubs are a handful with a .357 load, but that I reserve for the range or, in my GP100, hunting. All pocket well with the right pants, pocket holster, and steel-core belt. I now tell friends to test them all, if their budgets could handle a K6S. Been trying to get a friend whose Bersa Thunder jams a lot to try the LCR…

Looks like the cylinder went through a garbage disposal, ha! Love it! They are not pretty, true, but I always liked the brute ugly functional tool looks in a way. God forbid I end up shooting someone, I’m not too worried about it if it sits in some damp old evidence locker for a year. I would be upset over my Smith getting rusty.

Mike,

Try your LCR with the Bantam Boot Grip. You will be surprised how small and concealable the LCR becomes. Yet it is still quite shootable as long as you are not shooting 357.

You’re reading my mind George! Already ordered one! More to follow.

Agreed on the ‘homely’ appellation. Also agreed on the quality and ‘usability’ aspect.

Kinda like marrying an ugly woman who is a good cook? Ace2

Well, fortunately for us, we got both—lookers and cookers!

I daresay the LCR is growing on me. In the early days, I thought it was ugly, but not so much, now. It’s no beauty queen, but it does have a cool kinda charm of its own. Maybe I’ve been desensitized by the flood of Glocks, XDs, Sigs, and other square plastics?

One of my all time favorite guns to carry and shoot,

Mine is .357 and wears a Bantam boot grip.

I’ve put more rounds through it than I have with most other guns and it’s a very manageable shooter.

I planned on getting the 3″ version of this until my pop found a 2 3/4″ security six in stainless steel that he blessed me with for Christmas.

Nice find from your pop! Enjoy them both!

Mike, your attention to details still amazes me! I remember trying to convince people when the LCR first came out that its trigger and light weight were huge advantages. It’s truly a “shootable” revolver. Since I’m spending time in Tennessee now, I have become acutely aware of venomous snakes. I almost stepped on one in the dark and in the pouring rain when exiting from a sliding patio door. I’ve been carrying my S&W 40-1 with a CCI .38 Special shotshell as the first round just for snakes. While I love everything about it, the lightweight of an LCR would be a great choice. Also, the lighter price would be too. It would take the abuse of being a constant owb carried gun exposed to knocking around in the woods. Hmmmmm.

Shot a big rat snake yesterday in our big coop. Hated to do it, but I had already moved him out once with a broom.

The LCR .357 would be a great snake stopper.

Shot a Copperhead last week with my shotgun. It is mating season…Yikes. I found, however, that in my revolver, a Taurus 85, the CCI shot shells had the capsules creep out under recoil, locking up the gun. The snake was dead after shot one, but in a longer .357 chamber the gun would have kept functioning. I am now going to load my own snake rounds with gas checks and a crimp at top.

Hi there,

Wonderfully in-depth, no nonsense review, as usual. You left no stone unturned. I must say though I am thoroughly confused by your accolades, as I have been so many other times in the past from other reviewers, both professional and layman, who extolled the virtues of this revolver. I often wonder if the mini-14 edict applies to the LCR – in of ‘I guess you got a good one’. Anyone who is truly familiar with the mini-14 is aware of the unfortunate inconsistencies that exist with the rifle out of the box. Perhaps the same holds true of the LCR.

When it came out I couldn’t wait to get one, being that I have carried snubby revolvers as my primary on and off for 20+ years, and the LCR seemed to be the next best thing. I finally obtained an LCR in .38 special in 2013 or thereabouts. Sadly, I couldn’t have been more disappointed.

Firstly, I do not see how this revolver is frequently considered ‘affordable’ or called ‘a good value’, when the typical price runs around 400 to 450 bucks. I believe I paid somewhere in between that out the door. I then replaced the dismal front sight with a nice Hi-Viz just weeks after I picked up the LCR, as I found the stock front sight as wanting as the ones on the S & W j-frames. The sight itself was about $35 bucks, so that was no big deal. But the pin would not come out easily, so I then had to pay a gunsmith an additional $25 bucks to install it. I was now into the LCR for around $500. When I went to resell it about six months later, I found the used market was so flooded with them that I wasn’t able to get much more than $350 for it, and that was a bit more than the going rate due to the upgraded front sight and the extra accessories I sold along with the gun (pocket holster, speed strips, etc)

Next, I found the LCR to be not fun at all to shoot. The recoil, particularly with defensive ammo, was stout and painful. (I cannot imagine shooting .357s or 9mm through that revolver). On top of the recoil, I didn’t find the grip all that comfortable to begin with, and obtaining a high purchase on the gun as one should, resulted in the trigger consistently pinching the top of my shooting finger between it and the frame. By the end of each shooting session I had a damaged and bloody finger. I can assure you I am not the only person I know to have experienced this with the LCR.

Finally, while the pull of the trigger was relatively smooth I found the stacking too excessive to be called a great trigger, for my taste. I have since spoken with many, many other folks who had similar experiences. Unfortunately, unlike the myriad easily installed spring kits that vastly improve the triggers of the GP100 and my beloved SP101, there are no such kits available for the LCR due to the inherent design of the mechanism, as you so deftly and completely explained.

Anyway, I am very happy that you got some great examples of the LCR, and I very much enjoyed reading your article! Thanks for your hard work, as always.

Ian, thanks for the note. I’m sorry your maiden voyage with the LCR was a rough one. Sometimes, certain guns and hands are not a good match.

I’ve had a solid experience with the 9mm version of this gun, that you’ll hear more about later. I’m about to start working with the .38 Special version, but have no plans to play with the .357 one. I’ve fired the .22 Mag version of the gun, and thought it was OK. The issue with the rimfire guns is that the trigger needs to be heavier to ensure reliable ignition, and that can be an obstacle sometimes.

The SP101 is a tank, and even though the factory trigger usually leaves something to be desired, it can indeed be tuned to deliver a good pull. Glad you got yours where you want it. Iknow that gun will serve you well.

Thanks for reading!

My first snub was an LCR. Wasn’t a good idea, admittedly, but an unpleasant experience nonethless. Compared to what I remember of the LCR, I find my S&W 642 infinitely more shootable. I suspect the polymer lower, coupled with the uncomfortable Hogue grips, gave me even more felt recoil than normal. I find the trigger pull also lacks the “predictability”, for lack of a better description, of a J-Frame or a Taurus 85. I’ve thought about giving the LCR another chance at some point, but I always end up thinking it would be a bad idea. I really want to like Ruger revolvers, but I’ve only ever clicked with the GP100.

It happens. Sometimes a gun and a shooter just aren’t a good mix. That’s why we’re so lucky to have plentiful choices. I had a friend who used to rave about a particular model of self-chucker, but when I finally fired it, I encountered the worst trigger slap I’d ever experienced. It hurt so bad that I didn’t even finish the first magazine. Bad gun? No, just not a good one for me.

I’ve been really enjoying my 9mm LCR, and find it very manageable. I haven’t fired my .38 Special sample yet, but will be doing that soon. It’s very possible that I’ll prefer the 9mm, with its heavier, steel frame. We’ll see.

Glad your 642 is a good fit for you. They’re solid choices as well.

This old cowboy loves his 38 special ruger LCR. I carry her ever day. She my new 6 gun but with just 5 shots. I ride the range with her ever day She is light weight and deadly when I need her. I love this little LCR she is a great little gun for this old cowboy. Keep up the good work ruger. I love all your firearms

Mike,

Awesome review! This is by the far the most detailed write up on the LCR I have read, well done.

Have had an LCR .357 for several years now. I also had to warm up to the looks, but man do I love it. Certain 357s are not nearly as bad as you would think, and the extra few ounces help with the +P. I’m glad you gave it a try! Everyone I convince to try mine seem pleasantly surprised!

Great Job Mike

Thank you Sir! I think buying the .357 model was smart, to get the heavier frame. Wish I had done that.

Colonel, this was a superb engineering analysis, and one of your best writeups yet. Obviously a LOT of research and time put into this. Excellent write up on a gun that, comparatively speaking, makes the Mk VI .455 Webley revolver look like a royal blue Colt Python.

On the down side, I’m sorry, but in the UGLY versus GOOD COOK comparison, if she cooks as bad as she looks, I’ll get my ‘hook & ladder’ at Firehouse Subs instead. Face it, no one ever brags on taking the ugly gal home from the bar, no matter how good her ‘skills’ might be.

On the positive side, I have to admit that the LCR is as interesting a revolver concept as the Security-Six was back in 1970. ( I’ll still take a second generation Security Six, though ). The actual lockwork was essentially Ruger’s Double Action. Changing the geometry of the hammer, trigger, double action sear, etc, to give it a surprisingly good trigger pull, and then pinning it all in a polymer housing is, admittedly, innovative – then again, so was “Jack” Northrop’s YB-35. It must yield Ruger a much higher profit margin than its SP101.

I still can’t get with the polymer frame housing critical, constantly moving fire control parts all trying to go in opposite directions in a revolver that is intentionally designed not to be user serviceable. At least the Glock, S&W M&P 2.x, and SIG M17 are user serviceable. So is every other double action revolver that’s worth its steel. I’ll still opt for my M60-7 when it comes to small .38s.

I have no doubt that it might well be a rugged and serviceable platform, but it’s back to that UGLY versus GOOD COOK thing. I suspect even Deputy U.S. Marshal Raylan Givens would consider it as a viable, if not expensive, throwdown.

Thank you Sir! The thing I wonder is if the looks are startling to the Millennial crowd, who grew up with Glocks as a baseline? Us . . . ahem, seasoned shooters remember what revolvers are “supposed” to look like, but maybe the younger crowd wouldn’t bat an eye?

You’re probably on to something with the Millenials. If it’s polymer, or has polymer, then it’s a ‘Glock’ – even if it’s a Ruger LCR.

I’m in the OLD camp – revolvers are steel, blued or stainless, with nice grained walnut stocks.

I’ll stand right alongside you my friend. Gimme steel and wood grips.

I submit that handgun manufacturers have been attempting to make guns lighter and lighter. As if that is “good” for the shooter! It’s TONS cheaper for a manufacture to produce polymer wonders than it is steel shooters. So they lead folks to believe lighter is better. Marketing!

It may feel real light and comfy in the holster,,, but if you can’t go to training, or practice, and put at least (BARE MINIMAL) 100 rounds through it, I would question the integrity of owning such.

As an instructor I have opportunity to stand alongside new shooters constantly who are SHOCKED to see how much “bang” they just bought.

I thought the same, but Ruger had a surprise in store for me. I’ll discuss that in the coming weekend’s post—stay tuned.

As a pro-gun millennial, I’ll throw my opinion of the little gun in here. I don’t find the LCR to be ugly. When I got into guns, the LCR had already attained it’s market position, so it wasn’t new. I guess I missed the wave of “this new gun is ugly” that follows every new gun that gets announced, so I was kinda surprised when I read it at the beginning of this article.

Excellent. That’s exactly what I was wondering. Sometimes we carry a lot of prejudice (or “preference,” to be kind) into these things when we have a long history, but a fresh set of eyes can see things differently. The gun might look “ugly” to a person who grew up judging attractiveness by an old standard, but not to someone who entered the market after the standards had changed. If your baseline is the “old” M&P (the round kind), you’ll certainly have a different view of the LCR than someone whose baseline is the “new” M&P (the square kind).

True, Mike. I actually consider my K6S to be ugly, too. Function sold me on it. It is a tool, not a fine Italian shotgun I hang on the wall under glass.

Great great write up. I’ve had the 38 special version since very early on. It makes a great knock-around revolver and I’ve been very pleased with the accuracy. I quite tracking the round count at 2000. My only wish now is for a larger framed version for moon-clipped 45 ACP. My wallet would fly open for that.

Nice write up of a great, if a god awful ugly, wheel gun.

They shoot wonderfully, but I demand better aesthetics from a hammer. Being a good tool only goes so far. Life is too short to shoot ugly guns.

I continue to regret trading in my LCRx for something else that caught my eye at the time. I’m sure I’ll have another one in my life, hopefully sooner than later. Thanks for what is by far the most thorough recounting of LCR design I’ve ever come across Mike, and for making this clear case that this low-key little snubbie downplays the amount of serious thought that went into it. The LCR/x is further testament, in my opinion, to the fact that Ruger has not only been an industry leader with its revolver offerings, but one of the most innovative, by far.

My first wheelgun purchase was the Ruger LCR in .357. Not being “old school” and having no prior prior experience or expectations of beauty in a firearm, I fell in love with the LCR. Ugly? I find it to be a beauty. I went shopping to compare guns to find one that fit my hand and I could shoot well. Having only a basic handgun glass under my belt (dress), I was pleased to shoot the LCR at the gun store, and hit 10 center mass with no problem. This wheelgun may not be for everyone, but it is definitely for ME, and is my EDC. It fits perfectly in my Dooney & Bourke hot pink crossbody pouchette. A single top zipper, easy slide, and it sits perfectly at natural hand level. Not even my friends ask me why I am wearing a cross body and also carrying a handbag. Hot pink is one of my signature colors so my carry pouchette goes with whatever dress I am wearing. Yes, I wear a dress every day. Never pants, so no holster carry. For the record, when I take a shooting class, there is nothing a classmate wearing pants can do that I can’t do wearing a dress. Leggings help when doing groundwork! I’m a girly-girl Tomboy from a young age.

Thank you so much for this wonderful review of the LCR. While I am already in love with mine and support my decision 100% to shoot and carry a wheelgun, it is nice to have positive reinforcement from someone who has so much experience with wheelguns and sees the beauty (or not) in the LCR.

WGJ

Judy, it sounds to me like you found a winner on your first try! I wish we were all that fortunate (or lucky). Sounds like we could learn a lot from you.

I admit to not liking the LCR’s cosmetics at first, but as I grew to respect this gun, it got more and more attractive. The most important thing though, is what you think-—as long as you like it, that’s all that matters.

I do kinda wonder if I should talk to you and get some advice about finding a pink holster, as a gift for Justin . . . ; ^ )

Always GREAT to see you here in the comments! Let me know what you think of the 9mm LCR article.

Mike,

I do have a recommendation for that pink holster for Justin. There’s this sweet holster place in Texas… ordered a pink holster for the LCR. 😉

WGJ

Ha! We may need to talk . . .

Thank You for your comprehensive review of this wonderful revolver. Like you, I was skeptical of this little poly framed wheel gun. I started researching it and found one on sale for $319. I figured “what the heck” and pulled the trigger. It has the best out of the box trigger that I have experienced. At only 13 oz. it is now my EDC. I put Hogue Bantam grips on it. Doesn’t feel as good in my hand but conceals much easier. With the right ammo, it is comforting to know it’s on my belt. It’s stoked with Federal HST. Thanks again!

I am surprised that you did not mention that it is easy to short-stroke the tigger during the return and lock up the trigger.

While I like the ugly LCR, the quirky trigger return seems like a real problem.

Nix, I agree with your observation about the potential for short-stroking. That’s part of what I was trying to address when I wrote the following:

“ The only criticism I have of the trigger is that it suffers from a weak, or sluggish return compared to a S&W or Colt’s action, or even to the company’s own SP101/GP100. In the S&W design, a hearty rebound slide spring resets the trigger after sear release, but in the LCR, a small mousetrap spring returns the trigger, and it’s just not powerful enough to do it with the same authority.”

I also specifically addressed “short-stroking” in the companion article on the 9mm LCR, here:

https://revolverguy.com/ruger-9mm-lcr-field-report/

Which is all a way of saying that I agree!

I’m a ‘first year’ Gen-Xer [1966], my Grandfather [and three of my Uncles] was a Gun Engraver, and I’m a Gun Engraver / Gunsmith / Aerospace Engineer / Architect. I’ve been going to Gun Shows, and Gun-Shoots since I was 3 months old, I’ve owned and or shot just about every Revolver, Pistol, Shotgun and Rifle produced over the last 160 years, and I absolutely LOVE the look of the LCR ..

I think it looks beautiful. I love the rounded ‘flowing’ look to the backstrap, the deep-cut-away barrel, and the ‘transition step’ from polymer to aluminum. As a ‘1970s/80s’ kid/teenager, I have always hated the ‘squared off, notched’ look of, especially, the S&Ws above the grip – and combined with that deep “c” cut for the hammer [ that isn’t there on DA Only ] , it alway makes the gun look ‘un-balanced’ or ‘roughly finished’ ..

The GP100 [and especially the SP101 ] is a much better look. The higher grip that curves up and ends at the ‘squared off shoulder’ just gives the gun a more finished ‘flowing’ symmetry, but the S&W just looks like it has a block of metal above the grip that’s screaming to be ground off – it makes the gun look ‘ass-end heavy’ ..

I have always liked the ’rounded / blended-edge’ look of the GP1oo – even more so on the SP 101, whivh has an even better rounded / blended-edge appeal – it just, visually, looks stunning — and the LCR is really just a progression of that look. Too me, it’s much more attractive than the standard-fare, S&W , Rock Island [ Colt Detective Copy ] , Colt “Hip-Holstered Revolver” look that hasn’t changed in 100 years ..

However, I think the LCR is a] just a bit too light, with a bit too much recoil ; and b] just about 1/2″ – 3/4″ too short in the buttstock. I’ve never been a fan of “two finger” shooting – I prefer a more secure grip in a fire-fight ..

Yes, it’s better than nothing in an emergency, but with the right clothing, a SP101 can also be concealed with little printing. A slightly longer grip that allows for the bottom edge of your palm and your pinky to participate and maybe 1 extra oz of added weight placed in just the right place to reduce muzzle flip will go a long way toward making the LCR a superior pocket pistol shooter, with better control and faster secondary shot placement.

Thanks Brad, beauty is truly “in the eye of the beholder.” My tastes are not everyone’s tastes, and I’m glad you find the LCR so attractive. I appreciate the guns for their function, more than their style, but am still impressed by them. Hopefully you’ve read my separate review of the .38 Spl LCR and my Field Report on the 9mm version, where I describe my shooting experiences in more detail.