This review is a little out of the ordinary for us, and marks the first long-gun ever reviewed here at RevolverGuy. Though it ain’t a revolver, I can think of no better companion piece for a revolver than a like-chambered, lever-action rifle. Today we’re going to look at Henry’s Big Boy Steel Carbine in .357 Magnum. In my opinion this is one of the most interesting lever-actions out there.

Introduced in 2015, the Big Boy Steel certainly isn’t anything new. This is our first time out with it, though, and I feel like a RevolverGuy’s perspective might offer some new insight. As I mentioned, this review is a little out of the ordinary for us: our Revolver Testing S.O.P. doesn’t really apply, but we did what we could. We put 500 rounds through the gun, and thanks to my friend Jim, I was able to get this gun out to some decent distance. Thanks to the good ideas of a few Patrons, I also ran a few drills with this gun that I’ll discuss in a future article. I sincerely hope you all find some value here!

The Henry Big Boy Steel Carbine

The nomenclature of this firearm is a mouthful, so let’s break it down just a bit. The “Big Boy” indicates this particular gun in chambered in a traditional revolver cartridge. The Big Boy line is available in .327 Federal Magnum (I don’t know why but this chambering really grabs my attention), .38 Special/.357 Magnum, .41 Magnum, .44 Special/.44 Magnum, and .45 Long Colt. The “Steel” in the name indicates its construction and finish; Big Boys are available with yellow brass receivers, color case-hardened steel, an all-stainless all-weather model, and several more variations. Finally, the “Carbine” indicates this is a short-barreled model. The standard Big Boys have a 20″ tube, while the carbine sports a handy 16.5″ pipe. With nomenclature out of the way, let’s take a look at this little carbine!

As mentioned, the Big Boy Steel Carbine has a round, 16.5″ barrel. Some of the other Big Boy carbines have an octagonal barrel, but the Big Boy Steel’s round barrel represents a considerable weight-reduction. I found it hard to do shooting sessions of more than 150 or so rounds, even letting the gun rest during the session, because them lightweight barrel go so dang hot. The barrel is topped by a brass-bead front sight in a dovetail. I’ll address sight function a bit further down.

Below the barrel is the magazine tube. The magazine tube is affixed to the barrel at the muzzle end via another dovetail. One downside to the carbine-length Big Boy is a reduced magazine capacity. The standard Big Boy holds 10 in the magazine, while the carbine is limited to seven. As most readers are probably aware, the Henry is not a side-feeder. Loading requires removing the brass feeding rod from the magazine tube, dropping rounds in, and replacing the feeding rod. I’ll share a few thoughts on this later, as well.

Most of the magazine tube is covered by a checkered, walnut forend. Rather than a traditional barrel band, an steel end-cap, fitted with a sling stud, covers the leading edge of the forend. The rear sight is also affixed to the barrel. Markings on the barrel are tasteful and subdued. The area flanking the rear sight bears a simple “CAL .357 MAG/.38 SPL” on the right, and “HENRY REPEATING ARMS-RICE LAKE WI-MADE IN USA.” No instruction manuals, warnings, or other superfluous lines of text are present on the little Henry.

The barrel, magazine tube, and forend all terminate at the Henry’s steel receiver. The lack of a side-loading gate renders the receiver exceptionally clean looking. The only port present is the ejection port where the shiny, stainless steel bolt is visible. The top of the receiver is flat and is drilled and tapped for scope mounts or a section of rail. The left side of the receiver is complete clean save for a screw and a few pins.

At the bottom of the receiver is the gun’s most novel, eye-grabbing feature: its enlarged lever loop. The enlarged loop is (thankfully) not as exaggerated as some, but retains the functionality of allowing gloved hands to fit in the loop. On a personal note, I find the angular look of this loop quite pleasing. The trigger is pretty standard stuff, though there are no fewer than four unsightly mold marks on its right side. The rear of the upper portion of the receiver is demarcated by the hammer.

Moving backward we finally reach the walnut stock. Unlike the truncated front half of the gun, the stock is full sized. It offers sharp (and sharp looking) checkering in the grip area. It is equipped with a sling swivel stud, and capped with a very nice rubber butt pad.

Fit and Finish

I’ve heard a lot of good things about the fit and finish of Henry rifles. This exemplar mostly lived up to them. Finish on the Big Boy Steel Carbine is beautiful. I will point out, though, there are – and are not – three distinct finishes on this gun. The barrel/magazine tube, receiver, and trigger/lever loop all look different. I reached out to Henry for an explanation. My contact explained that all parts are finished with the same black oxide treatment. Some parts are polished to a finer degree before applying the finish which accounts for the differing appearances.

Running the lever makes it obvious that the fitment of the working parts is excellent. Though I haven’t fired it in a long time, I recall the lever on my dad’s Winchester Model 94 being rough and operating in fits and starts. The absolute smoothness and ease of operation of the Big Boy Steel Carbine was pleasant, though not altogether a surprise due to Henry’s reputation for smooth lever guns.

The furniture is exceptionally well done. The finish on the walnut stock and forend are dark and handsome. The checkering patterns are pleasing, and the checkering itself is a thing of beauty. Shape of both parts are excellent as well. The forend has a very comfortable swell, and the straight stock is ideally sized. Fitment of the furniture left something to be desired, however.

The forend was consistently a bit loose. Out of the box, I could apply downward pressure to the forend and generate maybe 1/16th of an inch of play at the rear. Tightening the opposing screws on its end cap alleviated this somewhat, though never completely. Around the fifty-round mark of the first range session, the forend began to work itself loose again. I never completely succeeded in fixing this little problem.

The play in the forend was exacerbated by a loosening of the stock screw in the receiver extension during my first range session. The screw holding the stock in place loosened itself under fire. This caused a tiny bit of play in the stock. Coupled with the play of the forend it made the gun feel somewhat rickety during recoil and when running the lever. I wasn’t immediately aware of what was going on, but after I discovered the play in the stock I applied some Loctite. This solved the aft portion of the problem. In fairness to Henry, this isn’t the only T&E gun that has required a little Loctite, lately.

I realize that this probably isn’t a gun intended for 100-round and up range sessions. Most of Henry’s marketing materials position the Big Boy Steel Carbine solidly as a hunting rifle. Even so, I’m disappointed that so much stuff loosened up on the gun after so few rounds. Fortunately, most of it was a fairly quick fix.

Sights

The sights on the Big Boy Steel Carbine are the traditional “open” sighted arrangement. The rear sight is a semi-buckhorn, and it is mated to a brass bead front. Windage adjustments can be made by drifting the front sight in its dovetail. One issue I take with the front sight is that it is only held in the dovetail by friction. Shortly after beginning my second range session, I noticed rounds impacting hard to the left. Inspection of the front sight showed that it had moved – visibly – to the right. This was despite no rough handling. I borrowed the range’s brass mallet and corrected the issue before finishing that session.

I assumed the issue was fully corrected. It was not; on the last range session I was conducting for-record groups at 50 yards. Again, I noticed rounds impacting left-of-center. Inspection revealed that the front sight had drifted out the right. I would really like to see this issue corrected, perhaps with a set screw to secure the front sight in place.

The rear sight is adjustable for elevation through two methods. Coarse adjustments are made by moving it up and down the stepped elevator. The rear sight blade contains an adjustable insert used for fine adjustments. After getting a coarse elevation, loosening the screw on the rear sight assembly allows the insert to slide up and down. The rear sight insert is also reversible; the default position places a “U” notch in the rear sight. The other option is a small “V”. The insert is marked with a white diamond that I found to be a boon to quick sight alignment.

I am far more experienced with aperture sights than open irons. All of the long guns I owned are equipped with some form of aperture or ghost ring. Still, I did not find the open notch rear sight to be a detriment to speed. I struggled with longer-range accuracy a bit with this sight, though. I found that the brass bead reflected a great deal of sunlight, obscuring a clean slight picture. Smoking the sight helped this a bit. I also found that the rounded profile of the bead made duplicating a precise, consistent aiming point somewhat difficult. To be clear, this is my issue, and many of you would doubtlessly do much better with this carbine than my groups below reflect.

The front sight’s repeated movement to the right did not inspire confidence in the sights. If I were going to deploy this carbine for any serious purpose I would strongly consider taking advantage of the flat-top receiver and mounting a red dot optic, and reserving the irons for emergency backup. How times have changed, huh?

Loading and Unloading

As I mentioned earlier, the Henry does not come with a side loading gate. Instead, rounds are fed into the magazine tube from the muzzle end. To load the Henry, rotate the magazine tube counter-clockwise. This frees the pin that secures it in place. Next, slide it out until the loading port in the magazine tube is unobstructed. Drop your ammo in, then reinsert the loading rod.

The rod will now be under tension from the spring it contains; do not let it go! It will go flying downrange. As it is brass it is somewhat more susceptible to damage than the gun’s steel components, so I’d certainly be careful when handling it. When the magazine tube is fully inserted, align the retaining pin with its channel, depress it fully, and rotate clockwise to secure it.

Unloading is a bit easier, and certainly safer than unloading a side-loader. First, remove the magazine tube fully. Next, invert the gun, and the rounds in the magazine should come falling out. After you have done this reinsert the magazine tube and run the lever a couple of times just to verify the gun is truly unloaded.

Additional magazine tubes are available through Henry for a very reasonable $21.50. If I were going to own one of these rifles, I would definitely have a couple of spare tubes.

Before testing the Big Boy Steel Carbine I wasn’t super hot on the magazine tube concept. And apparently I wasn’t alone. I’ve read comment after comment, on review after review denigrating the under-barrel, end-of-tube loading system. After running this one for a while I’ve got to be honest: I believe most of the criticism is somewhat misplaced. While perhaps not as elegant as a side-loader, this isn’t a bad system. If this is what’s keeping you from buying a Henry Carbine, I don’t think it’s as big a deal as you’re making it out to be. Stay tuned – I’ll cover this more in a future article.

Hammer & Trigger

The MIM trigger is light and fairly crisp. In fact, it’s much crisper than I expected on a lever action rifle. With the hammer back there is the slightest bit, maybe 1/32″, of free travel. After the free travel is taken up there is the tiniest amount of creep. It is seriously a tiny amount. Once this is overcome the trigger breaks very cleanly. Measured trigger weight on this specimen was about 3 3/4 pounds. The hammer on the Henry rifle is narrow but sharply serrated. Pulling it back is actually an enjoyable process, with a very satisfying “click” to mark its full rearward travel.

Henry rifles lack the additional crossbolt safety found on newer offerings from competitors. In fact, no external safety is present at all. I appreciate this, as doubtlessly do many others. It contributes to the receiver’s clean appearance, and it isn’t a safety that might be engaged when you need to make a quick shot.

The Big Boy Steel Carbine (and other rifles in the line) are, however, equipped with a transfer bar safety. This permits it to be safely carried with a round in the chamber. Safely lowering the hammer is very similar to the process Mike detailed for decocking double-action revolvers: point the gun in a safe direction, control the hammer, pull the trigger to release the hammer, RELEASE THE TRIGGER to disengage the transfer bar, and lower the hammer.

Reliability

Reliability with .38 Special ammunition was good enough for plinking purposes. The provided manual advises that if .38 Special ammunition is going to be used, only 158-grain are appropriate for the Henry Carbine. The overall length with a 158-grain bullet comes closer to mimicking a .357 Magnum cartridge and is more likely to feed smoothly. The manual also warns that 110-, 125-, and 130-grain ammunition not be used at all because of feeding issues. I fired 68 rounds of GECO 158-grain .38 Special. Even with this longer .38 ammo I had some occasional halting performance when returning the bolt to battery. Personally, I would reserve .38 Special ammunition for those fun range sessions, or perhaps single shots at smaller game.

Performance with .357 Magnum ammunition was much better. I fired a variety of bullet types through the Henry, including FMJ, JHP, Buffalo Bore’s Hard Cast Solid, and a couple of Hornady’s FTX bullets. The Henry seemed to function identically with all of them. Which is to say pretty well, once I knew what I was doing. Initial sessions saw a few choppy cycles of the action, which led me to an interesting conclusion.

Reliability with this type of manually-operated arm seems to be as dependent on the operator as the gun. I noticed that when on my last session with the Big Boy Steel my friend Jim had a couple of stutters. Operating the lever with some authority helps, as does just developing a feel for the gun’s cycle of operation. After 500 rounds both the action and I seem to have smoothed ourselves out, and I’m perfectly confident in the reliability of the Henry Carbine.

Range Sessions

Over five range sessions, I fired 512 rounds through the Big Boy Steel Carbine. Of these, most were .357 Magnum loads from eight manufacturers. Bullet styles ranged from FMJ to Hornady’s FTX, to JHP to Hard Cast Solids with wide meplats.

01 December 2019

– 75 rounds Perfecta 158-grain FMJ

– 44 rounds GECO 158-grain FMJ, .38 Special

– 8 rounds Buffalo Bore 125-grain JHP

– 14 rounds Buffalo Bore 158-grain JHP

– 8 rounds Buffalo Bore 180-grain Hard Cast Solid

– 2 rounds Speer 135-grain Gold Dot Short barrel

– 1 round Fiocchi 148-grain wadcutter, .38 Special

– 1 round Winchester 130-grain Defender JHP, .38 Special

Total: 153 rounds

02 December 2019

– 100 rounds Perfecta 158-grain JHP

– 8 rounds Speer 125-grain Gold Dot JHP

– 8 rounds Speer 158-grain Gold Dot JHP

Total: 116 rounds

13 December 2019

– 50 rounds Remington 110-grain HTP JHP

– 25 rounds Perfecta 158-grain FMJ

– 15 rounds Hornady 135-grain Critical Duty FTX

– 5 rounds Buffalo Bore 125-grain JHP

– 5 rounds Speer 158-grain Gold Dot

– 5 rounds Speer 125-grain Gold Dot

Total: 105

17 December 2019

– 24 rounds GECO 158-grain FMJ, .38 Special

– 30 rounds Remington 110-grain HTP JHP

Total: 64 rounds

26 December 2019

– 16 rounds Speer 125-grain Gold Dot JHP

– 26 rounds Speer 158-grain Gold Dot JHP

– 5 rounds Buffalo Bore 158-grain JHP

– 11 rounds Buffalo Bore 180-grain Hard Cast Solid

– 6 rounds Remington 110-grain HTP JHP

– 5 rounds Hornady 140-grain LEVERevolution

– 5 rounds Fiocchi 148-grain wadcutter, .38 Special (chamber loaded)

Total: 74 rounds

Accuracy

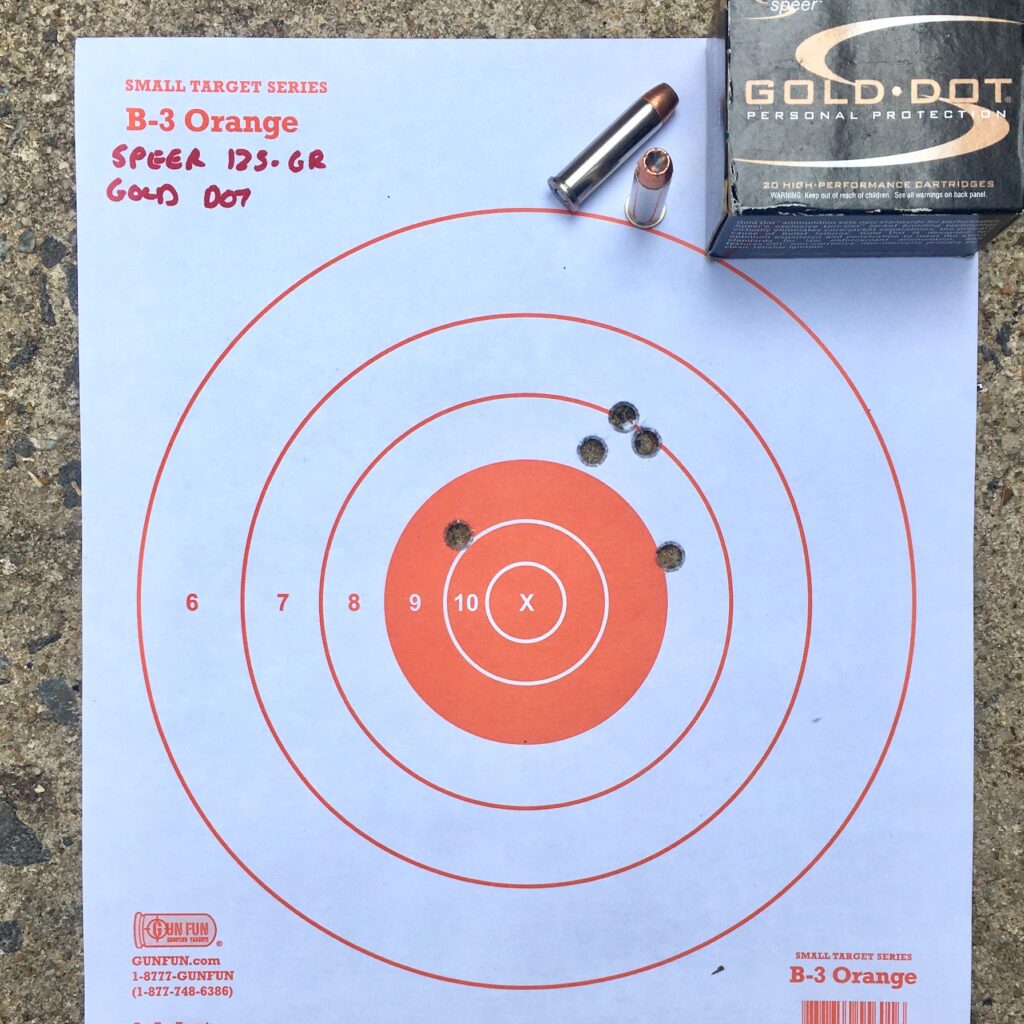

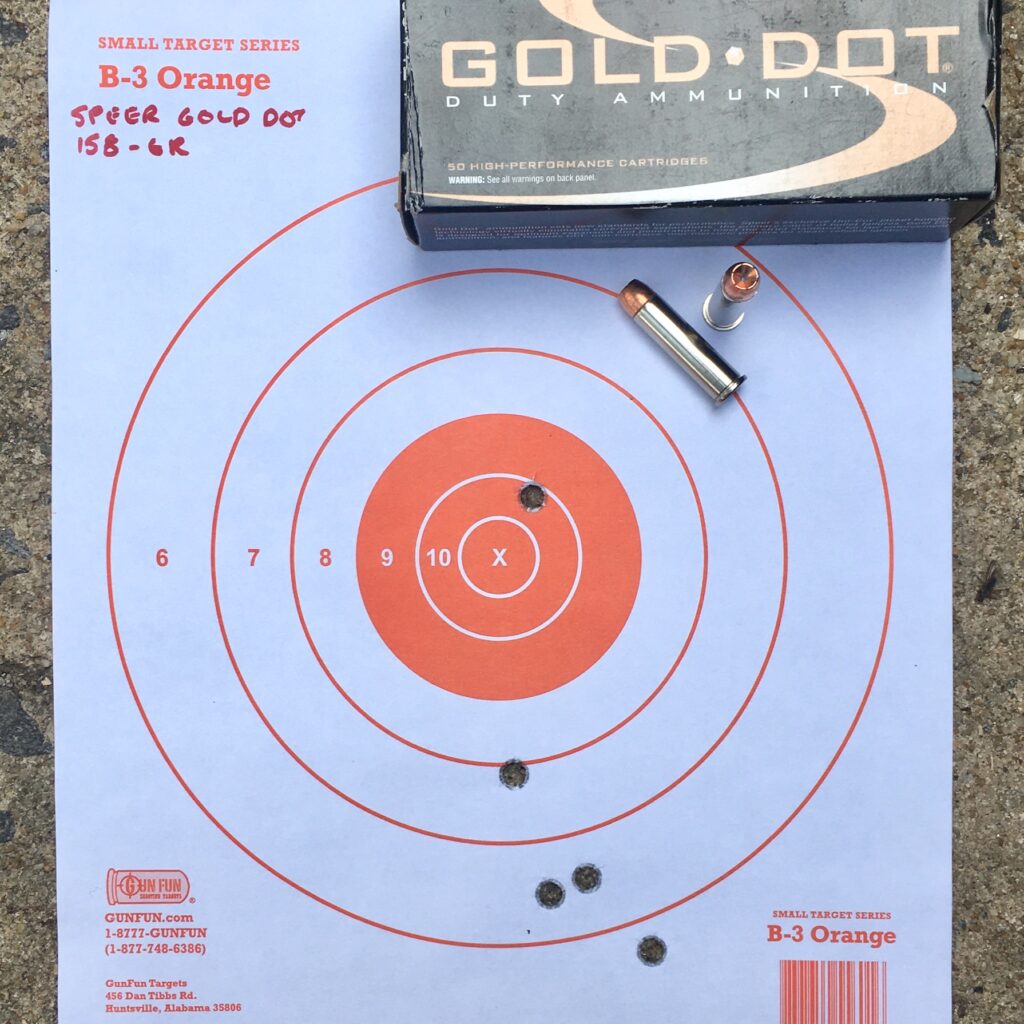

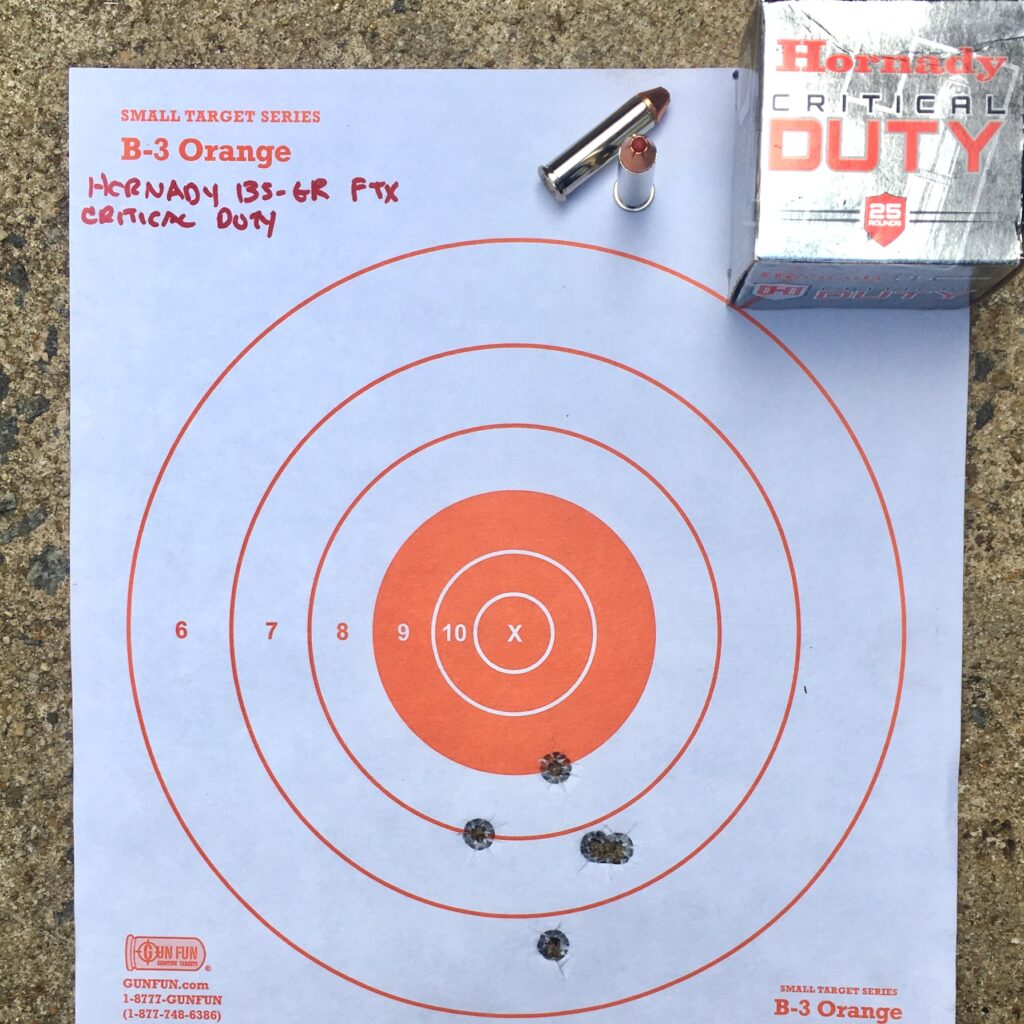

I decided to test accuracy just a bit differently here. I chose to shoot a couple of defensive loads – Speer’s 125- and 158-grain Gold Dots, and Hornady’s 135-grain Critical Duty – at 30 yards. I fired these groups offhand. While I hesitate to call my rate of fire “rapid,” I was moving as quickly as I could shoot accurately.

I haven’t provided measurements for these groups. Needless to say, though, I would have no problem with the accuracy of the Big Boy Steel Carbine at traditional self-defense distances. I’d have a hard time replicating them with a pistol or revolver at that distance and speed; you could do much worse than this carbine with any of these loads.

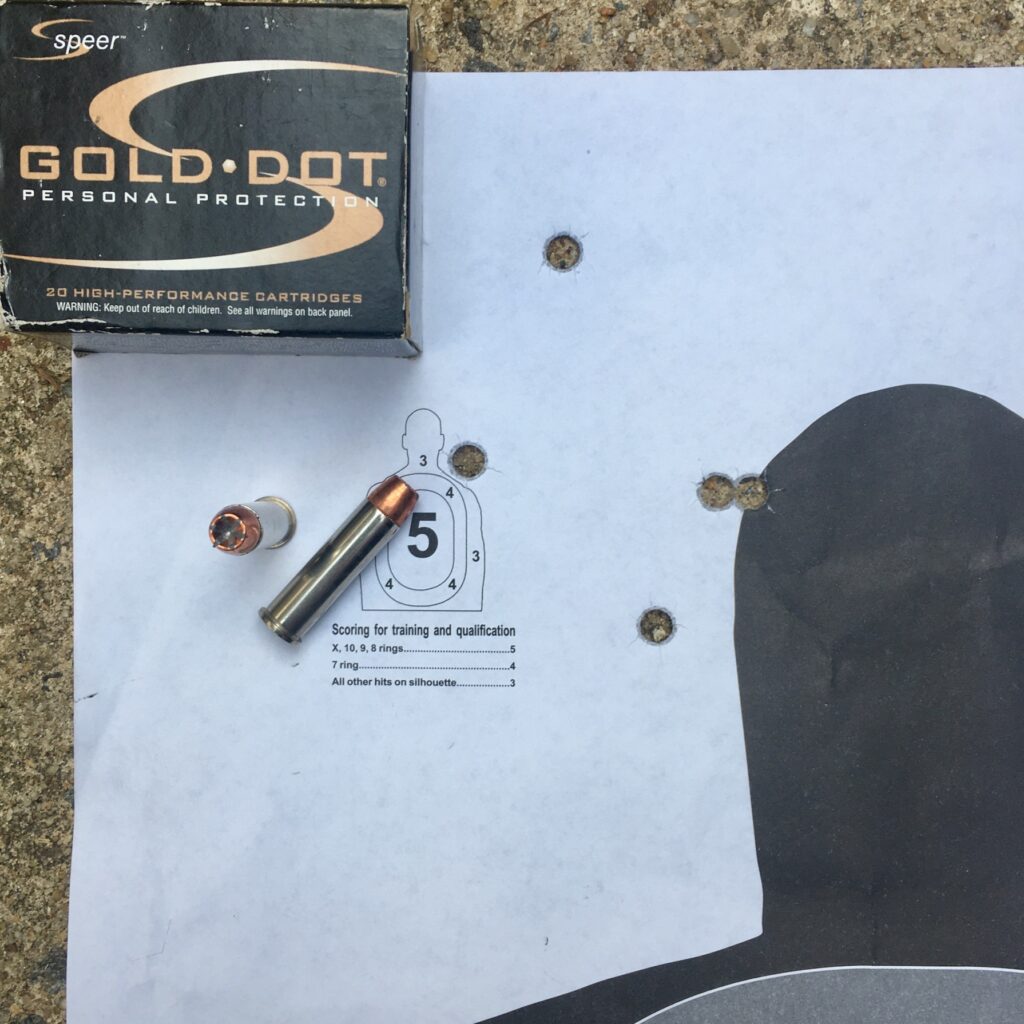

I also had the opportunity (thanks to my friend Jim) to get the gun out to 50 yards, where I fired three loads for groups: the Speer 125-grain Gold Dot 158-grain Gold Dot, and Buffalo Bore’s 180-grain Hard Cast Solid. I would have liked to have shot a few more groups (and fired a few at 100) but unfortunately I ran out of time.

Note that the extreme high and low points of impact with the two Gold Dot loads were mostly the result of using different points of aim to facilitate printing two loads on the same target. The 125-grain load was shot with a 6 o’clock hold on the head, and the 158-grain Gold Dot was shot with a 6 o’clock hold on the center orange oval. Also keep in mind that the windage on those groups is a result of the front sight’s movement in the dovetail.

These 50-yard groups were fired from a rested, sitting position. Keep in mind these groups are probably limited not by the carbine but by me.

Carbine Velocity & Energy

And speaking of, I ran some bullets over the chronograph. I was extremely interested to see what kind of difference the Henry’s 16.5″ barrel would make. Of course I have poured over charts online…but that’s not quite the same thing as getting out and seeing those numbers appear on the chronograph. I was extremely pleased in two things.

| Henry Carbine |

S&W 686-3 | Increase |

| Speer 125-grain Gold Dot JHP |

||

| 2054.33 FPS 1172 ft-lbs |

1363.50 FPS 516 ft-lbs |

690.83, 50.6% 656, 127% |

| Speer 158-grain Gold Dot JHP |

||

| 1623.20 FPS 925 ft-lbs |

1062.50 FPS 396 ft-lbs |

560.7, 52.7% 529, 133% |

| Buffalo Bore 158-grain Barnes XPB JHP | ||

| 1812.40 FPS 1153 ft-lbs |

1349.40 FPS 639 ft-lbs |

463, 34.3% 514, 80.4% |

| Buffalo Bore 180-grain Hard Cast Solid | ||

| 1781.50 FPS 1269 ft-lbs |

1282.83 FPS 658 ft-lbs |

498.67, 38.8% 611, 92.8% |

First, velocities out of the carbine were flat-out impressive! The Speer 125-grain Gold Dot broke 2,000 feet per second on every shot. Both Speer bullets showed a greater than 50% increase in velocity and ~130% increase in muzzle energy from the carbine – a major increase. Secondly, the energy produced by some of these bullets from the carbine is amazing – almost 1,300 ft-lbs from the 180-grain Buffalo Bore loading!

The second thing that impressed me was the performance of the Buffalo Bore ammo. The Speer Gold Dot has never been accused of being a slouch. Comparing the Speer and Buffalo Bore 158-grain JHPs, there’s not even a contest. I regret not testing Buffalo Bore’s 125-grain load but through my own fault didn’t have them on hand when I had access to the outdoor range. Fortunately Chris Baker recently provided us some data on this load. His velocities were over 2,100 FPS (faster than any .30 Carbine load tested) and performance in gel was a strong combination of penetration and expansion. I would certainly consider it a contender for defensive use.

Handling

Handling of the Big Boy Steel Carbine is superb. This is one of the first things I noticed about this rifle. The Big Boy Steel Carbine always seemed to come to the shoulder right on target. The short, 34″ length is much appreciated, too. At only an inch longer than my BCM Recce-14 (and cutting a much sleeker profile), the Big Boy Steel Carbine is exceptionally maneuverable. Shouldering this rifle is a pure pleasure.

At just a hair over 6.5 pounds the weight is very nice; enough to tame the fairly mild recoil of the .357 Magnum, but not so much to make carrying a chore. The Big Boy Steel Carbine balances right at the receiver.

I did dress the Henry up just a bit with some leather provided by Diamond D Leather. They were kind enough to send us a butt cuff and a sling, both of which you’ll see in the next article on lever guns, and as the subject of their own review. The butt cuff placed the balance a little further back, but this was completely offset by the sling. Again, expect full reviews of this stunningly beautiful leather very soon.

I also want to address recoil. Shooting full-house .357 ammo out of a revolver is not something I do a whole lot of, because of cost, wear and tear on my guns, and – not least – the recoil and muzzle blast. Shooting full-power Magnum loads out of the carbine was never a chore. The hardest-hitting loads I fired – namely, the stuff from Buffalo Bore – let you know you were shooting something, but weren’t uncomfortable at all. My girlfriend even embraced .357 Magnum loads in the Henry Big Boy Steel. Though to my knowledge she’s never fired a Magnum cartridge from a revolver, she took to it with aplomb with the carbine.

the Bottom line

I’m not a hunter, so I might be a poor judge of the Big Boy Steel Carbine’s hunting prowess. Honestly, I think it would be just fine out to a hundred yards on appropriately sized game. It’s an easy carrying stick and is accurate for the task at hand. For my purposes, this would make a fine defensive carbine. I wouldn’t mind this as a “truck gun” for those long-distance road trips. My “truck” is an SUV, and the Big Boy Steel Carbine fits into my spare tire compartment. Add in a revolver and a box or two of ammo and I’d feel exceptionally well-heeled.

The Henry Big Boy Steel is a handy, handsome little carbine. Despite what I felt was some room for improvement, the Henry Big Boy Steel performed where it mattered most: with reliability and accuracy. The Big Boy Steel Carbine is a near perfect companion for your favorite .357 Magnum revolver!

Stay tuned for the next installment, where I’m going to talk about really running this carbine.