Sixty degrees doesn’t seem cold. In the depths of winter, we many of us long for mercury to climb break the fifties. Here in the mountains we treasure our sixty-degree nighttimes. Sixty is considered by many to be an idyllic, comfortable outdoor temperature.

A Balmy 60 Degrees

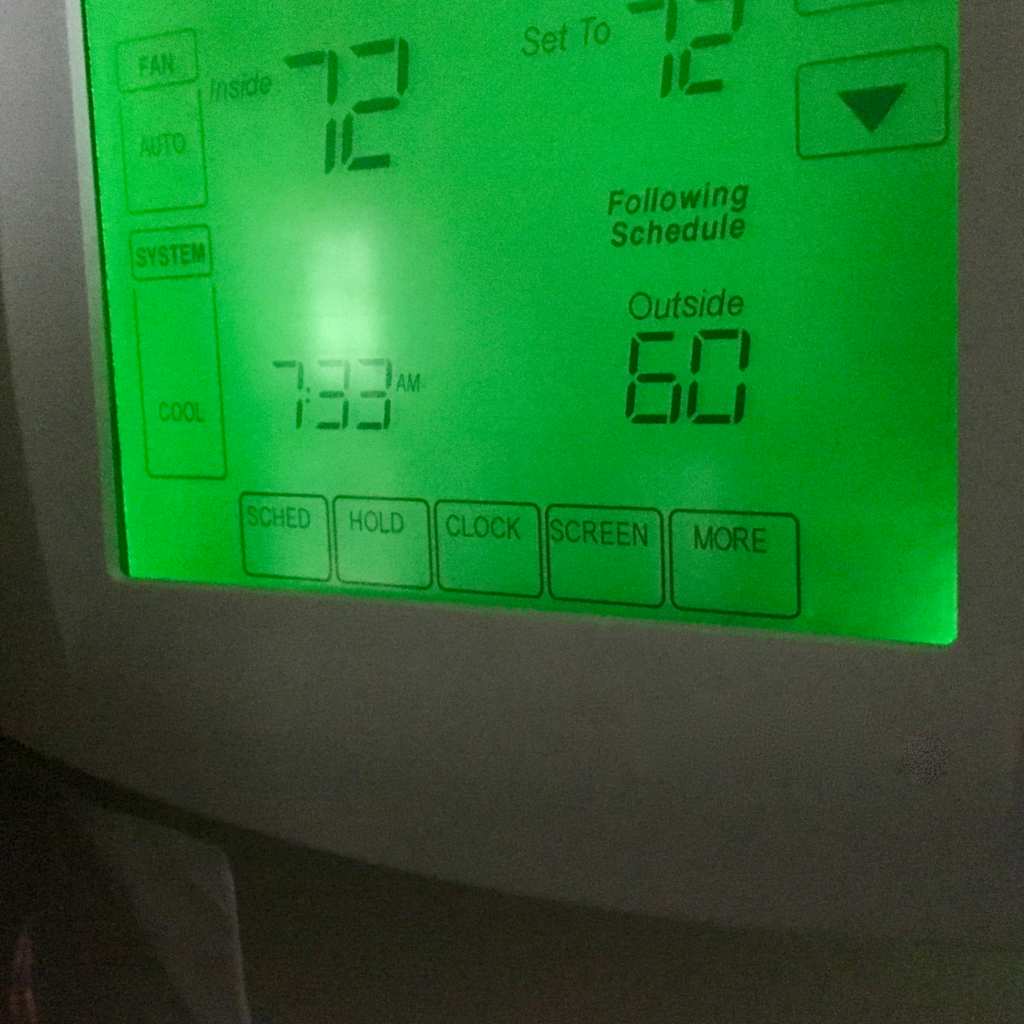

I was pondering this from the comfort of my home the other night, while observing the outside temperature was at an even sixty. We had just come in from sitting outside, enjoying the cool mountain air. A cool breeze was lightly stirring, carrying a little moisture from the recent rains. We’d decided it was bedtime and as I lay down my mind fixated on 60 degrees.

Sixty is certainly not a temperature we consider a “killer.” It’s not hot and it’s not cold. With the human ability to don a jacket or adjust the thermostat, sixty degrees Fahrenheit is generally considered by many to be an ideal temperature. But what if you had to be outside in it? What if you couldn’t come inside, take a hot shower, and throw on a sweatshirt?

In the elements you’re faced with much more than just the number on the thermometer. Add that damp, heat-robbing breeze back into the equation. Also add any moisture your clothing and hair collects, from the ground, the vegetation, the lightest of rains, or from your very own body. Any contact with the ground – sitting down to rest, for instance – will sap even more heat from your body. Don’t forget that the cumulative effect of these factors can be greater than the sum of its parts.

Now imagine spending all night – sundown to sunup – outside at an ambient temperature of sixty degrees. Sixty – a mere twelve degrees outside our ideal “room” temperature – can suddenly seem threatening. Though Jack London’s famous To Build a Fire was set on the Yukon River with a tooth-chattering temperature of seventy-five below, below-zero temps aren’t required to induce hypothermia.

The ability to build a fire is an essential human skill. A fire can be many things. Under the appropriate circumstances a fire can be cheery, terrifying, seductive, or cozy. Fire can cook, purify, temper, and entertain. Though something of a novelty for many of us city dwellers (and former city dwellers!), fire is brutally utilitarian. A fire could be a life-saver, even at a balmy sixty degrees.

To Build a Fire

I consider myself to be pretty good at getting – and keeping – a fire going. As a kid it was my job to stoke the fire in our house every morning. As an adult I always keep a ferrocerium rod on my person, and I built plenty of fires in SERE school. I’ve made scores of fires on camping and backpacking trips, and have geeked out on primitive fire-starting methods. I was recently humbled, though.

The other night we had friends and their kids over. S’mores were the draw for the kids, so warming our backyard fire pit was in order. “No problem,” I thought. “I’ll have a fire going in no time!” Even with all the benefits of modernity – a long-necked, “torch” lighter, tons of dry newspaper, etc. – all I got was smoke. So, I grabbed a couple more pieces of newspaper. And got more smoke. On and on it went.

We’d had a torrential downpour earlier that afternoon. I assumed it would be no big deal. Hubris overcame me, and I forgot to give nature her due. As I blew and gathered more twigs and relit the fire, some old mantras began to play through my head:

“If you can’t snap it, scrap it!”

“Don’t pick up wet wood off the ground. Break dead branches from the trees.”

“If it’s wet, split it open to expose the dry inside.”

In the end, I succeeded. It wasn’t my proudest moment, but I finally fed the fire enough paper to get the thing going. S’mores were eaten, kids and adults were happy. That evening’s events did fall on the dry tinder of my mind, though, and we get to the real point of this brief article.

Training & Knowledge vs. Equipment

As I mentioned earlier, I carry a firestarter on my keychain. It’s a tiny little sparking tool. Though certainly less capable than my lighter and half a dozen pieces of newspaper, I know for a fact this tool will start a fire. To use such a small, simple tool effectively requires a decent amount of skill, though. The tinder has to be very fine, and very dry. It has to be optimized to catch and hold tiny sparks. The tool must be used correctly to produce sparks, and to avoid knocking your tinder all over the place.

What does it really take to use such a diminutive tool effectively? Knowledge, skill, and practice. If you know how the tool works, how fire works, and how to make effective tinder you’re off to a great start. If you’ve started fires with this tool before, even better. If you’ve practiced it often and recently – well, now you’re probably about as effective as the tool with let you be.

And after that downpour, you’d need to be as effective as you can be with your chosen tool. After realizing that a tiny dip in temperature could wreak such havoc on a human, I was appalled at my difficulty in starting a fire. Obviously I’m out of practice. And obviously I need to get back into practice. I know what one of this summer’s side projects for me will be…

Takeaways

Though it might not be immediately apparent, there are a couple big things I would hope you take away from this post.

The first: I think you should know how to build a fire. It is a potential life-saving skill. If you hunt, hike, camp, off-road, kayak, fish, or engage in any other pursuit in the great outdoors, the likelihood of needing a fire to sustain life is probably similar to that of needing a handgun to defend life.

Even if you know how but haven’t started a fire recently, you should make a point to practice. Your level of ability should be commensurate with the tools that you carry. Teach your kids to do it. Toast marshmallows. Make an event of it. Practice (and recency of experience) is incredibly important just before you potentially need it. Make it part of your sport, like carrying a handgun is part of your day-to-day.

The second: Equipment is useless without training, knowledge, skill, and practice. A few weeks ago Mike pondered the question, “is the snubby enough gun?” After my recent foray into wet-weather fire-starting, I was pondering, “is this enough firestarter?”

The less-capable our equipment is, the more capable we must be. Shooting a small, snubby revolver with high effectiveness is objectively more difficult than shooting a larger, heavier firearm. It requires training, knowledge of capabilities and limitations, and – most importantly – frequent practice. As I mentioned a few weeks ago, “getting good” isn’t the same thing as “being good”. You have to work to stay good. This goes for all skills we work to maintain.

The Bottom Line

Over the last few days I’ve written half a dozen equipment review articles for the upcoming weeks. As gun guys, RevolverGuys, whatever – we love equipment. Popularity of equipment reviews – measured by any standard – beats training articles by orders of magnitude on this blog. But training is important, knowledge is important, skill is important. Sometimes we all need a reminder of that. Get out and practice. Push yourself. Fail. Learn from it.

After reading George Stewart’s “Earth Abides,” a good friend taught himself to make a fire with a bow drill. I was very impressed. If my little fire-starter block got lost, I’d be in for hypothermia.

Good reminder and good post, sir!

Always a good reminder to practice the basics. I’ve never built a friction fire before, but I know it’s something I should practice.

Another big one for me lately is constructing emergency shelter.

Good to see you, Matt! As you might imagine, building a friction fire depends sometimes on the materials at hand, but mostly on knowledge, practice, and recency-of-experience.

Challenge accepted! I need to do some shelter-building, too.

If that’s October’s monthly challenge, you can go ahead and count me out.

We should all have the means to make fire. I did it ONCE with a bow. Won’t do it again if I don’t have to, but I’m glad I know how! Certainly carrying a knife is sufficient to make a bow, but I think other means are better. As an aside the title caught my eye since I’m actually a direct descendant of London’s. Weird how that comes up sometimes.

Wow, Riley – that’s super neat! I haven’t read any of his stuff in awhile, but I definitely came up reading it (along with Louis L’Amour, Old Yeller…)

I have a zip bag of dryer lint in each vehicle. It makes very cheap tinder. I also have a fire starter steel along with a Zippo that gets topped off every few days. Fire can be man’s 4th best friend.

You’ve piqued my interest. What are the other three? I’m assuming #1 is a dog.

Good stuff Justin. Was watching Cast Away a few weeks ago and decided to try his fire plow method. Watched a YT video and gave it a shot. Got smoke but not enough embers to get the tinder going. I’m in good shape for my age and it was very tiring very quickly! Will have to try again…

Have a bow kit I’ve busted flame with occasionally with just to be able to. That being said all my kit’s contain 1-2 bics, fero rod, and a small vile of vaseline soaked cotton balls. Those puppys will burn for a good 10 minutes…

Good stuff Justin,

Since your using a ferro rod, try quadruple-ought (aka) four-ought steel wool. Take a piece, spread/fluff it out a little bit, place that in your birds nest …. strike it up. The reason for placing it in your birds nest is that the real fine steel wool, once it’s lit, is not something you really want to handle. The little pieces of hot, burning steel can burn you. Anyway, steel wool is pretty much water proof and you can actually light it with a battery if you had to. It does not last as long as the vaseline/cotton ball thing, but it does burn very hot.

Thanks again,

Another Mike

Nice post, Justin. Esp. the “Bottom Line” at the end.

I’m amazed at how many people who consider themselves “outdoorsy” these days don’t know how to properly build a fire in less than ideal conditions, how to sharpen a knife, or how to use a real compass and map. First aid training is another category that comes to mind that doesn’t get enough attention.

While I enjoy your reviews, I’m looking forward to more skills-oriented content as well.