In a previous installments of the “Fighting Leather” series, we looked at some landmark police duty holster designs, such as the Jordan Border Patrol style, the clamshell, and the various front break designs from makers like Berns-Martin, Hoyt, Bianchi, Safety Speed, Rogers and Safariland. Today, let’s look at another popular option for 20th Century police–the cross draw.

Military roots

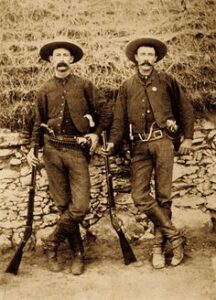

It’s clear that the popular cross draw holster had its roots in the military scene.

Author Richard C. Rattenbury, in the seminal book, Packing Iron, notes that “the military’s adoption of [the Colt 1851 Navy Model] pistol for mounted troops in 1855 dictated a change in associated gunleather.” Prior to this time, the larger and heavier guns (a Colt Walker was 15.5 inches long and 4.5 pounds!) used by dragoons and cavalrymen were typically carried on the saddle, but Colt’s new, trim military revolver opened up new opportunities to carry the weapon on the belt. Rattenbury quotes (then Captain, later famed Civil War General) George B McClellan, suggesting in 1856, that American cavalrymen, “should follow the Russian system and always carry the pistol on the waist belt,” after observing this practice in the Crimean War.

Since cavalrymen were already habituated to carrying their sabers on the left–so they could be drawn and wielded by the right hand–practicality dictated that the new pistols would be carried on the right side of the belt. They would be arranged with butt forward, to permit a left-handed draw when the right was already full of sharpened steel, or a reverse “cavalry” draw with the right, when necessary.

Owing to military’s penchant for standardization, this cross draw carry of pistols lasted for many decades. The cavalry troopers who fought the Indian Wars in the American West later deviated from this pattern, and often carried their revolvers in locally-procured, strong side, California or Mexican Loop pattern holsters, with the butt of the gun to the rear, but the cross draw remained the Army’s baseline standard until the era of The Great War. It also remained a popular choice for cowboys and other armed citizens of the era, who often took their cues from the military—sometimes because they were veterans, sometimes because surplus military gear found its way into their hands.

A new home for an old idea

As paramilitary units, it’s no surprise that American police forces were influenced by the military standards of the day, and readily adopted the cross draw holster. This is especially so, because many police forces actually used surplus military uniforms and equipment as the basis for their early police duty uniforms.

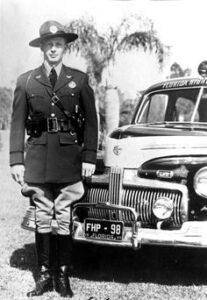

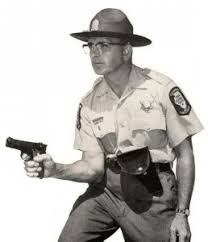

Twentieth Century American cops weren’t in the habit of carrying sabers, but the cross draw holster neatly solved other problems for them. As we’ve discussed before in prior installments of this series, American police officers of the era favored revolvers with long, six-inch barrels that increased the sight radius and maximized the energy from their cartridges. This was especially true for the western lawmen who policed non-urban areas where shots could be more distant, and for highway patrolmen who worked around vehicles all day, and needed the best penetration possible.

These large and heavy sixguns were good tools for the job, but they could also be difficult to carry with comfort, especially as police officers entered the motorized era and found themselves seated behind the wheel of a car with increasing frequency. The longer tubes on those sixguns would poke into the seat and jam the gun upwards if they were carried too low on the belt. As a result, cops of the era who didn’t want to switch to shorter, 4” guns usually added a swivel to the holster’s shank or hangar, so it would pivot and lie parallel to the bench seat, or they adjusted the ride of the gun to place it higher on the belt.

The latter solution worked OK, but could make it awkward to draw the gun out of a top-draw design, as the gun had to be lifted so far to clear the muzzle that the presentation became awkward. “Trick” designs like the front break or clamshell holster were good solutions for this problem, because they allowed the gun to come out of the holster with a forward motion, without lifting it, first.

Strengths

The cross draw accomplished the same feat. It allowed the holster to ride reasonably high on the belt for comfort, while allowing the gun to come out the front of the holster for a handy draw that didn’t involve any high-lifting hijinks.

In fact, the draw from a cross draw holster could be very comfortable and fast, indeed. Legendary sixgun expert Elmer Keith observed that “many fat or big men prefer a cross draw holster and this is also very fast.” He also noted that, “the gun comes out naturally and smoothly” from a cross draw holster (Sixguns, Pages 152 and 170).

For an officer in a seated position, the cross draw holster offered a significant advantage over a strong side holster, because it was faster and easier to draw from. When drawing from a strong side holster in a seated position, a shooter has to lean forward or twist the body to create space for the elbow to travel to the rear, so the hand can find the gun. The shooter can flare the elbow out to the side, instead, to facilitate the grasp without creating this space, but the presentation becomes more awkward and slow.

In contrast, a seated person can easily reach across their body and grasp, then present, a weapon carried in a cross draw position in the confined space of a car. Importantly, for threats that present on the driver’s side of the car, it’s also unnecessary for a right-handed officer to track the weapon across the steering wheel and dash to aim it towards the left, as the gun is virtually pointing in that direction already when the presentation is complete—just a little rotation of the wrist, as the elbow drops, will quickly point the gun at the driver’s side window. For a cop concerned about being ambushed in the patrol car, this was a very favorable characteristic of the cross draw as a duty holster.

The cross draw also provided good access to the gun with the weak hand, in the event the officer’s strong hand was injured or otherwise occupied. Keith had noted this in 1961, when he advised dual-wielding shooters in Sixguns that, “with cross draw holsters either gun can be used with either hand by simply bending the wrist or reaching back under the butt of the gun with the fingers.”

Fast-forwarding almost 70 years, trainer Mas Ayoob also notes that the cross draw position is friendly to shooters with injuries that might negatively influence a strong side carry and draw. Got a bum shoulder that interferes with your ability to raise a gun up and out of the holster? The cross draw fixes that nicely. Got a hip or back injury that makes carrying on the strong side painful? The cross draw allows you to carry a reasonably-sized, fighting handgun on the other side without much difficulty.

Weaknesses

The cross draw holsters also came with their own set of weaknesses, though.

The first issue with the cross draw is that it could take extra time to present the gun to the target, depending on the orientation of the shooter’s body. If an officer could blade his body and place his gun side towards the opponent, he could get the gun out and have it on target fast, but if he began squared off to the threat—or worse yet, bladed in the opposite direction, to protect his gun by moving it out of the suspect’s reach—the gun would have to track across a longer arc to get the muzzle on target, and this motion could also be more easily fouled by an opponent at close quarters, who only had to pin the officer’s sweeping arm across his body to “stuff” the draw.

That lateral tracking of the gun was a significant concern for police trainers and administrators for safety reasons, as well. Although a safe and effective cross draw presentation can be made without endangering others (see the photo sequence above), most coppers who drew their guns from cross draw holsters would swing the gun from holster to target in a lateral arc that would muzzle fellow officers and innocents along the way. As police firearms training became more commonplace and formalized in the years following World War II, there was less enthusiasm for a holster that encouraged such unsafe handling practices when officers were lined up side-by-side on the firing line. Nobody wanted to be placed on the gun side of an officer with a cross draw during training!

In the field, butt forward carry of the gun was problematic when dealing with suspects in close quarters. In the traditional “field interview” position, with the gun side bladed to the rear, a cross draw holster would conveniently orient the gun in a way that a suspect could easily grasp it. Blading the opposite way would reverse the presentation of the gun, but also place it closer to the suspect, which was equally unappealing, from a weapon retention standpoint.

As American police came under increasing attack in the violent 1960s and 1970s, this critical flaw became even more apparent, and doomed the cross draw’s future as a uniformed duty holster. A tragic example of the cross draw’s most glaring deficiency occurred on August 5, 1972, when California Highway Patrol (CHP) Officer Kenneth D. Roediger, from the East Los Angeles area office, was fatally shot with his own gun by an ex-con he was trying to arrest. During the vehicle stop, Officer Roediger and the suspect got into a struggle, and the suspect landed on his back in the street, with Roediger straddling him on top. As Officer Roediger tried to pin the suspect’s shoulders to the ground with his hands, in preparation for rolling him over for handcuffing, the ex-con reached up and drew the officer’s revolver from his cross draw holster, then shot him through the heart with his own gun.

Tragically, the holster had been given to Officer Roediger by his highway patrolman father. As a result of this incident, the cross draw holster was banned for uniformed duty use by the department (interestingly, the clamshell holster remained in service for a while longer–grandfathered in for those officers who had already placed them into service—but wouldn’t last much longer, either). Many other police departments took notice of this and followed the influential agency’s lead, also banning the cross draw for patrol.

The cross draw would survive a short while longer in the CHP and other agencies as an off-duty option, or as a holster for plain clothes officers (like detectives), but its days as a uniformed duty holster were over.

Makers

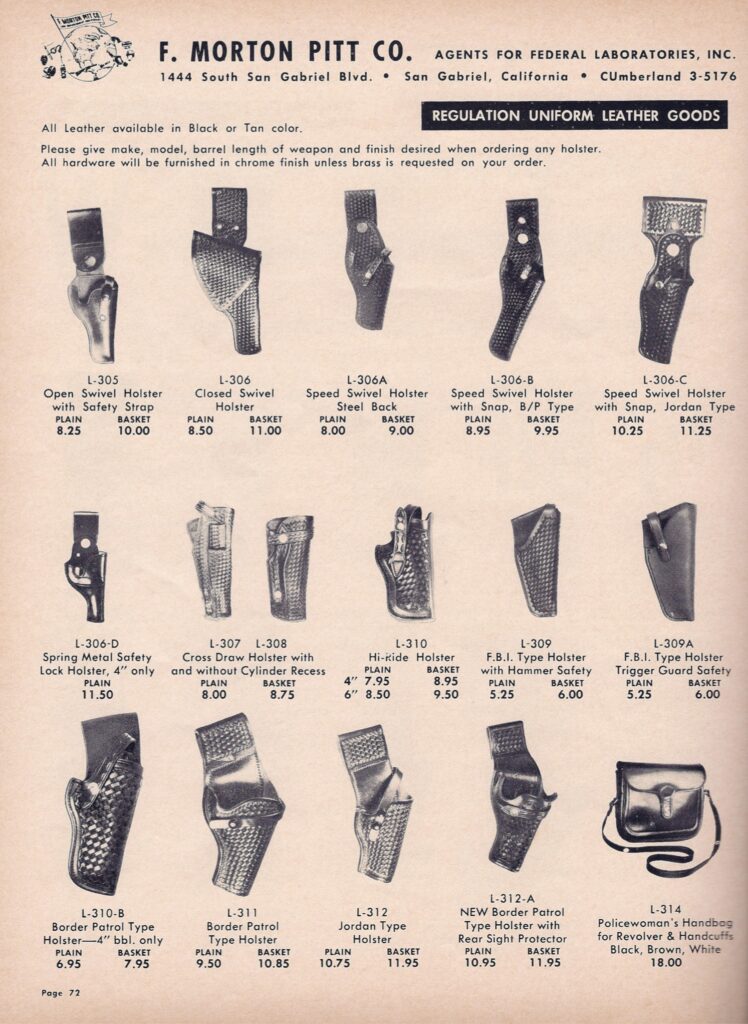

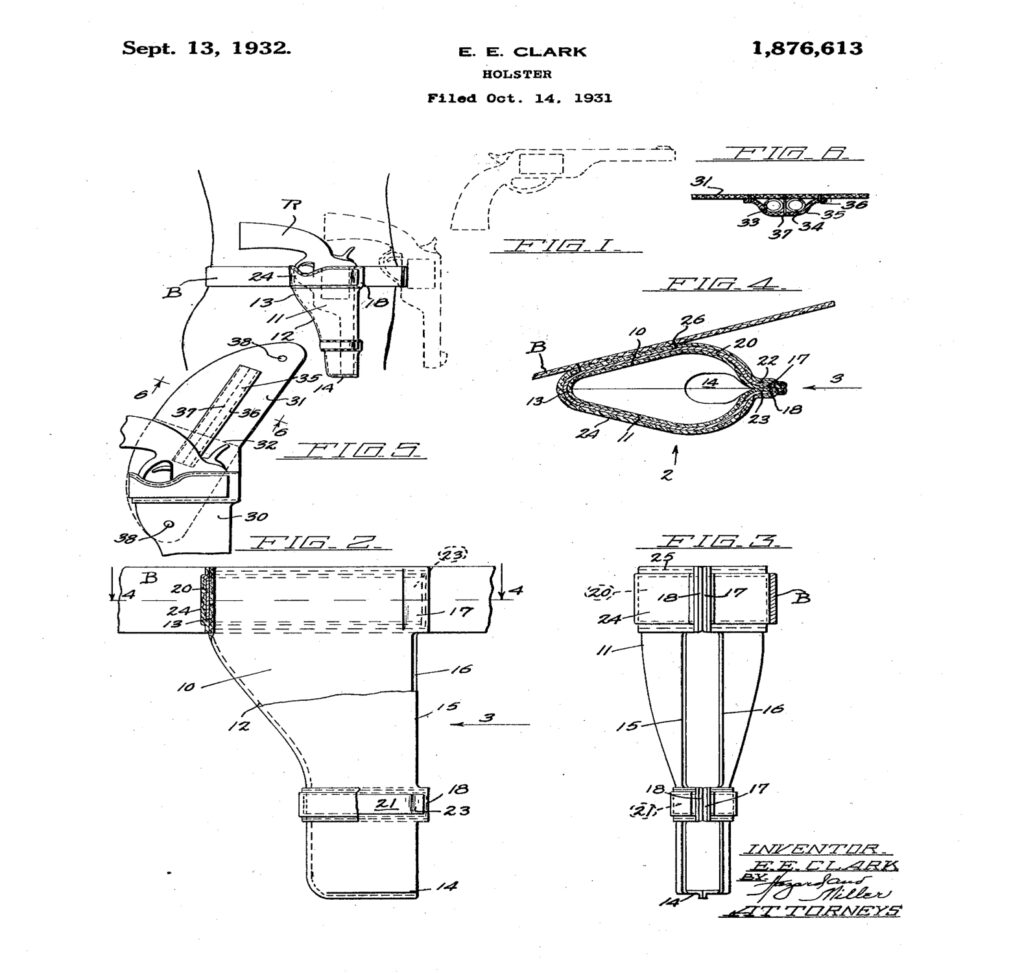

In the heyday of the cross draw, the design was produced by all the popular makers of police leather. Clark Holster—located in Los Angeles, CA—had an early interest in this design, since it was Edward E. Clark who held a patent (dated 13 September 1932) for a front-draw holster that was held closed by spring tension. Even though his patent drawings portray a holster with the butt of the gun carried to the rear, this concept was readily adapted to the cross draw holster.

Rivals Lewis and Hoyt Holster (also of Los Angeles) made their own variations on the design. Ace Holstorian Red Nichols notes in his essential reference, Holstory, that Richard Hoyt was once employed by E.E. Clark as a salesman, circa 1930, so he may possibly have gained his appreciation for the design while employed there. It appears their fellow Kansan Ed Lewis was influenced by his association with Clark and his products as well. Interestingly, while the Clark and Lewis designs route the spring below the cylinder, Hoyt’s version of the cross draw routes the wire spring around and above the cylinder, starting below the bottom edge of the cylinder, then following the leading edge of the holster around the mouth of the pocket, at the top.

Nichols notes that later on, Bucheimer-Clark (founded by the acquisition of Clark by J.M. Bucheimer) improved on the basic design (as executed by Clark and Lewis) by increasing the length of the spring that was sewn into the holster body, so that it reached the top of the cylinder pocket. This increased spring tension helped to improve the retention qualities of the holster.

In later years, police holster giants like Safety Speed and Safariland (with the assistance of E.E. Clark’s son) introduced their own cross draw designs, with at least Safariland making them into the 1980s, before they disappeared.

Styles

Many of the cross draw holsters—particularly those made for plain clothes, or concealed, carry–were made without any kind of retention strap. The only retention for the revolver was provided by the strength of the spring, and (in the case of the Hoyt, and others who copied the Hoyt trademark) the squared cylinder relief inside the holster.

Most cross draws that were designed for uniformed duty use included some kind of flap or safety strap though, to secure the weapon in the holster. This safety strap was typically designed to be popped open by the trigger finger of the shooting hand, as it swept the gun forward and out of the holster. Some of the concealment versions used these straps as well, but they were more common on the uniformed duty holsters, it seems.

My experience in playing with the Safety Speed version you see in these pages indicates that the safety strap could have benefited from a longer tab, to help pop the snap more easily, but it’s still rather ergonomic and it seems like it affords a much faster presentation than the “suicide special,” “gun bucket” top draws that were so popular in police service in the same era from the ‘30s to the early ‘70s. It was a lot sexier, too!

Today

Outside of the shoulder holster, the cross draw style of holster has largely disappeared from the gun scene today. There’s a few models out there from custom makers—like Sam Andrews— that are still available, but you’re unlikely to see many of them in the catalogs of the most popular, mass-production makers. The ones you’re most likely to find are the so-called, “dual position” field holsters, like the Galco Switchback, that offer an extra belt slot to permit cross draw carry for hunters and other outdoorsmen.

The days of opening the F. Morton Pitt or George F. Cake police supply catalogs and seeing a host of cross draws for duty and off-duty carry are long gone, but there’s no doubt that the cross draw was an influential and popular police duty holster, that earned the sobriquet of “Fighting Leather” in its day!

Mike,

Simply Rugged’s pancake holsters are setup for strong side or cross draw.

Great writeup on what was my first department issued rig — the Mixon 3″ belt with cross draw and drop boxes. UGH.

One positive attribute ( ?? ) for the cross draw rig, okay, so its only attribute, was the ability to wedge a Kel-Lite (for those old enough to remember that name) between your side and the gun stock, to hold it in place while you wrote out a traffic citation at an accidence scene when it was Zero Dark Whatever at night.

Another quasi-positive attribute at the time – our cars did not have cages in them at the time. Procedure was in traffic stops where a moving violation earned a citation (not to be confused with a commendation) was to bring a driver back to our vehicle, sit them in the passenger seat while we wrote out a ticket. The schtick sold to us was that the passenger couldn’t just reach over and snag our revolver. (rolling eyes).

But in defense of the cross draw — they looked really killer on the Air Force’s Air Police units during the old SAC days.

Thanks for sharing the firsthand story with us! It’s amazing how both the equipment and police tactics have changed through the years, isn’t it?

I could probably put up with the cross draw holster better than the wool tunic in the photo of the FHP Trooper! My Lord, that must have been miserable in the humidity!

“The Apes,” ah yes. Mirror-shined boots, with white ladder-laces, crisply-pressed blues, smartly-worn and gleaming helmets, perfectly-adjusted ascots, armbands, and a Model 15 worn cross draw, with gleaming cartridges in loops . . . almost makes you want to cry when you see the wrinkled new utilities and the fungus boots.

Thankfully, the tunic went out of regular street use long before I got involved, but, it is still used for formal and ceremonial occasions, most notably at funerals. Patrol School classes in the colder months will wear them at graduation if the academy decides to opt for that.

I remember the ‘APes’ as a kid at McCoy AFB in the late 50s, early 60s – just looking at them was intimidating. Isn’t quite the same these days.

As a field holster, cross draw is great. I have a Bianchi 111 holster for my Mod 66 that is dual position capable. When slinging a rifle on the right side, cross draw is out of the way. Cross draw is more comfortable getting on and off the tractor, ATV, truck etc. I also have a cross draw “driving holster” with a snap on/off belt flap that rides high, very handy and out of the way. For general concealed carry; strong side on a good belt and holster. Start with a good belt; you will not regret it.

Yes, a great choice for a belt-worn field holster! All those cowboys were onto something.

As a duty holster, they leave a lot to be desired!

Yep, crosssdraw can be a great option for the sportsman. In addition to the uses you mentioned, cross draw also works well in tree stands and kayaks or canoes. The Galco DAO and SAO work great for my field use because they are set up for strong side or cross draw and have a secure snap (always nice when your revolver is still there at the end of a rough trek). Crossdraw also doesn’t interfere with a slung rifle.

Excellent points Eric, thanks for the personal testament.

Mike, great article. I’ve liked everything I’ve read of yours.

When I became a policeman, 31 years ago, my agency had abandoned cross draw holsters and year-round Long sleeve wool uniforms about a decade earlier. Most of the troops thought “good riddance”. Also, the powers that be refused to waste taxpayer money on frivolous things like car air conditioning. I’ll bet that hot looking Florida Highway Patrol man’s car did not have AC.

Thanks Brent! Glad to have you here, and I’m glad you’re enjoying the site.

I’m sure FHP had 2-60 air conditioning—standard for all police cars with more than about 30K mileage! ; ^ )

In the late 80’s I was a deputy sheriff and used a “Rampart” cross draw as a off duty/plain clothes holster.

The unusual design canted the butt back with the muzzle forward. This seemed to enhance concealability, I was able to carry my 4506 underneath a sweater without problem. It was quite comfortable. Of course it was either lost or traded away years ago. I still favor a cross draw for field use.

Good stuff, Mike! I’m unfamiliar with “Rampart”—was it a model name, or a manufacturer?

Model name safari land model 555

Search rampart cross draw in duck duck go, should be the first image result

Found it, thanks!

Cross draw has a lot of appeal for sitting down in a car (or anywhere, really). I think a cross draw shoulder holster could work, depending on the person, and probably the choice of firearm too.

I remember while assigned to prisoner transportation, the driver of the van wore his revolver in a cross-draw, it was much more comfortable while driving and ever so easy to access if needed. Some of us carried in shoulder holsters that are essentially cross-draw holsters carried in a higher position off of the belt…if doing plain clothes court duty I personally like the upside down holster that secured my S&W M65 3″ round butt..I cannot remember the maker but the revolver was secured with the muzzle up butt down and the arm was retained by elastic tension…IIRC, it was the same as what was used in the movie “Bullitt” . A handful of years ago my local gun club was having a defensive handgun course. I took the course as I’ve been wanting to get some of the more modern training…there was an old boy who showed up with a very nice S&W M19 4″ in a cross-draw. The instructors took one look at that rig and asked the gent if he had another holster..He asked, “Why?” and the instructors explained that while on the firing line and being directed to draw and fire from a holster you are muzzle sweeping all of those in the arc of the draw…he was not very happy as he was unaware of their range rules. I offered to lend him a strong side holster and he accepted as he wanted to shoot the courses, too. I left and returned with a suitable rig and the training turned out to be better than I expected.

Glad to hear from you Sir! With your interest in the upside down shoulder holster, you’ll be sure to enjoy this wonderful post on those rigs from friend Red Nichols (of Bianchi fame): https://www.holsterguys.com/post/post-30-so-you-have-a-bianchi-no-9-inverted-shoulder

Way late to adding $.02 to the discussion, but here’s my contribution:

I agree with the field-use of a cross-draw. Sitting on a stool or up in a stand waiting for Bambi or Porky, the cross-draw negates a lot of the movement needed to pull the pistol when it’s time for a shot, and it’s a lot more secure than waiting with the gun in your lap. BITD, I carried a backup 1911 or S&W 669 in a horizontal shoulder holster (when the weather was cool enough for a jacket), but was always cognizant of how easy it would be for the ‘interviewee’ to grab it. Never a comfortable thought, but it kept me on my toes.

At the academy–ca 1980–a new young sheriff or undersheriff had a nifty looking cross-draw-rigged duty belt. When another rookie (never mind who) asked him about anybody ever trying to take his gun, he said he hoped they would; then he could demonstrate his super-duper who-flung-dung-kung-fooey skills on them. Fortunately for somebody, he ended up getting sick and had to drop out of LEO work.

You might surmise that I’m not a fan of cross-draw for serious social situations; you’d be right.

Sounds like the voice of experience talking to me, Ace. I think it’s an important clue that we don’t see these used anywhere in policing these days—-unless you count shoulder holsters as part of the same family, and I don’t (although some of the same limitations apply).

Some classics should stay in the past.

Great points all around on the cross-draw. I prefer it with my longer barrels as sitting is difficult with these on the strong side.

I have a quick question, though. Where did you find the holsters for the speed strips? I’m assuming that’s what I see in the picture at the top. I have a couple speed strips for my .44 Redhawk and have been looking for holsters. Are these magazine holsters that happen to fit this caliber?

Rick, those are vintage dump pouches. They predate the creation of strip loaders, and were designed to carry loose rounds. However, when the Bianchi Speed Strips came on scene, many makers changed the dimensions of their dump pouches to incorporate enough room for the strips, too, and they became Speed Strip pouches, in effect.

You can find plenty of old ones for .357/.38 on EBay, but for the .44 you’ll probably need to go custom. You can have new ones made to spec by places like Purdy Gear, Simply Rugged Gunleather, Andrews Custom Leather, and Lobo Gunleather. You might be able to talk El Paso Saddlery or AE Nelson Leather Co. into making one, as well, even though they don’t catalogue anything like that anymore.

Best of luck on your search!

I cannot find good data on the number of law enforcement officers who died because their service sidearms were yanked from the holster by an enemy and used to shoot the officer. Cross-draws went out of service because of ONE 1972 death? Strong-side holsters evolved from flapped or open-top with perhaps a safety strap to thumb-break all the way to high-security level retention holsters. If strong-side gun grabs were not an issue, there’d be no holsters designed to resist gun grabs. Military techniques to remove sentries make both approach and attack from the rear. Humans are constructed to fight to their fronts and it’s easier to secure a firearm holstered in front of the body with the butt forward than it is to secure a pistol with the butt to the rear carried in the strong-side position.

So, where’s the numbers?

Hi Alan, you won’t find them, because they’re not systematically tracked in a uniform way, and they’re not shared publicly when they are. Agencies tend to hold that kind of information very close, and you have to be inside the profession to have a sense of the nature and size of the problem.

Note that Officer Roediger’s death was just the proverbial “straw that broke the camel’s back” for his agency—it was not the only reason, nor the only event, which led to the cross draw being disapproved for duty use. Besides, there were other factors, outside of disarmings, which led to its demise, as we discussed in the article.

I have to politely disagree with you about your statements on weapon retention, based on my own training and experience in this area. The cross draw doesn’t offer any advantages in a retention scenario, and actually suffers several disadvantages, compared to a strong side rig. Note that cross draw holsters for uniformed duty use were worn close to the point of the hip, not significantly forward of the centerline—-basically in the same place, in mirror fashion, as a strong side holster. This presents the same challenges as a strong side rig, with the additional complications of having the gun carried in a fashion that makes access easier for an attacker than for the officer.

Thanks for reading and commenting. I hope I was able to answer your questions.

I’m one of those ‘fat guys’ who benefits from a Desantis ‘Roscoe’ crossdraw rig for my Model 442.

But another advantage of my crossdraw holster is that when wearing a heavy leather motorcycle jacket the 442 is much easier to draw than if holstered on a strong side belt holster (it’s practically impossible to draw that way).