The most common question about revolver ammunition right now is, “where can I find some?” The demand-induced shortage which began in 2020 is still very much with us, and finding some ammunition—of any sort, as long as it’s the right caliber—is foremost on the buyer’s mind.

However, when we’re not in the middle of an ammunition crisis, RevolverGuys can be more particular about choosing bullet weights, styles, brands and velocities. As they ponder the available choices out there, one of the most common questions that arises concerns the “+P” and “+P+” flavors of .38 Special ammunition. RevolverGuys—particularly new ones–will commonly ask, “can I shoot .38 Special +P (or +P+) ammo in my gun?”

Well, I’m glad you asked.

Roots

We’ll get to the “+P” part soon enough, but the story begins with the birth of the .38 Special, itself.

The venerable .38 Smith & Wesson Special started life in 1898, as a longer derivative of the .38 Long Colt cartridge, which had served as America’s service cartridge since 1892, when Colt’s New Army and Navy Model revolver was adopted by the armed forces.

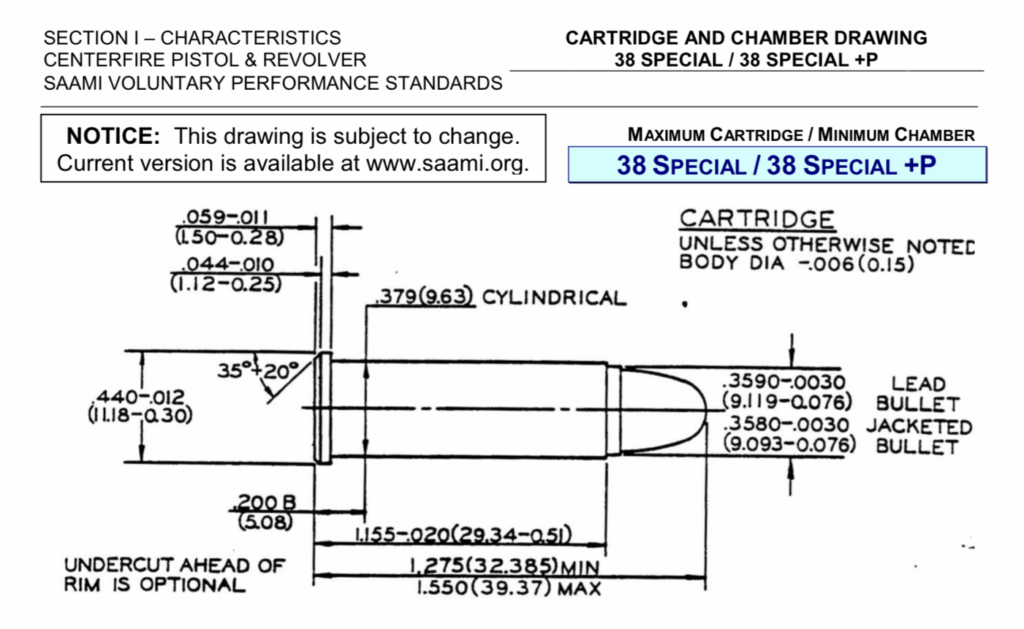

The .38 Smith & Wesson Special’s case was 1.155 inches in length, compared to the 1.035-inch case of the .38 Long Colt. The longer case allowed the Special to hold a bigger charge of black powder than the Long Colt (about 21 grains, or 3 grains more than the shorter round). This larger charge of propellant allowed the Special to throw a bullet of the same diameter, but weighing 8 to 10 grains more (158 grains, as compared to the 148 grain, military version of the Long Colt, and the 150 grain commercial version), at approximately 100 to 150 feet per second (fps) faster than the Long Colt.

This improved performance was welcomed, as the .38 Long Colt had already proven disappointing, even before it developed a poor reputation for stopping Moro tribesmen in the 1899-1902 Philippine-American War. The U.S. Army had previously been equipped with the 1873 Colt Single Action Army revolver, and the .38 Long Colt just couldn’t measure up to the performance of that gun’s powerful .45 Colt chambering. Therefore, any effort that could improve on the capability of the .38 caliber, double action, swing-out cylinder, revolver concept was appreciated–especially when it was housed in a gun as compelling as the Smith & Wesson .38 Hand Ejector Military & Police (or .38 Military Model 1899), the forebear of the legendary Model 10.

Under Pressure

Although it was born as a black powder cartridge, the .38 Special quickly made the transition to smokeless powder, within about a year of its introduction. Smokeless powder is not as bulky as black powder though, so as a result, there is a surplus of room in the .38 Special case, when it’s loaded with smokeless propellant.

There’s enough room in the .38 Special case to load with a much greater volume of smokeless powder, but this would create a dangerous overpressure situation that could lead to blowing up the gun and injuring the shooter. Although the temptation was always there to hot rod the .38 Special, its roots as a low-pressure, blackpowder cartridge could not be ignored. The guns of the day weren’t up to a more powerful loading of the Special. 1

A crush on SAAMI

In 1926, the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) was formed to provide an element of industry standardization in the design and manufacture of ammunition. Previous efforts at industry standardization, in the years leading up to World War I, had been successful, but temporary, so SAAMI was formed to fill the void.

One of the primary functions of SAAMI is to provide detailed specifications for the dimensions and performance of various cartridges, to include the maximum average pressure (MAP) that a cartridge may be loaded to. Manufacturing companies that agree to adhere to SAAMI standards (most American, and some foreign, manufacturers do) are bound not to exceed these limits.

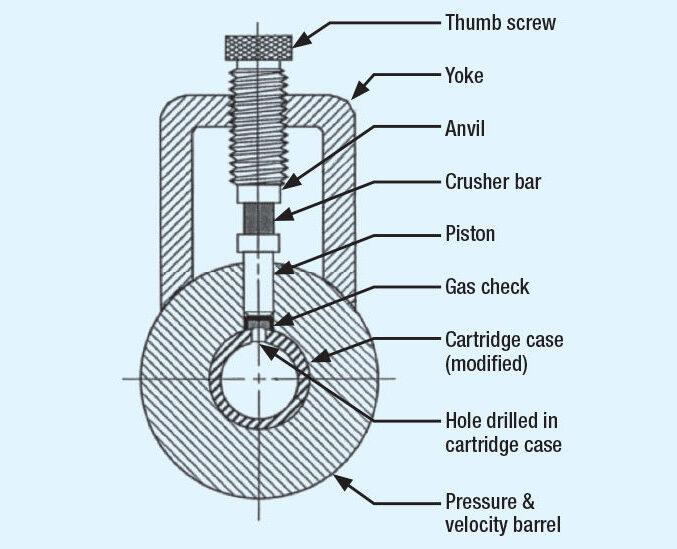

In the early days of SAAMI, the MAP for a given cartridge was determined and measured using a copper crusher method. In this method, a piston is fitted into a hole that is drilled into the chamber of a test barrel. When a cartridge is fired in the test barrel, the pressure activates the piston, which bears on a carefully machined and calibrated copper crusher cylinder. Measuring the amount of compression in the copper cylinder allows engineers to determine how much pressure was developed in the chamber, expressed as Copper Units of Pressure, or CUP.

The MAP for the .38 Special in this system of measurement is 17,000 CUP. By comparison, the .38 Special Proof Round, which the manufacturer uses to test and certify firearms, is rated at 29,500 CUP, and the .357 Magnum has a MAP of 45,000 CUP. 2

Wanting more

By the 1960s, the .38 Special cartridge had been the predominant round in American law enforcement service for over half a century, but despite its long run, there were still misgivings about its perceived lack of power. 3

The standard 158 grain lead round nose (LRN) load that filled the chambers of almost all police revolvers wasn’t known to be a powerful stopper, and when things started heating up in America with race riots, widespread political violence, and a tremendous spike in violent criminal activity (to include record numbers of assaults on police) in the mid-1960s, American police clamored for more effective ammunition.

The .357 Magnum was a popular choice in agencies that would permit it, but many police and civic leaders were hesitant to approve Magnum ammunition for their officers, due to political concerns about “police militarization.” Additionally, many police and civic leaders didn’t want to spend the money necessary to rearm their forces with new weapons in a different caliber. 4

As a result, there was an increased push for a more effective .38 Special round which began in the 1960s, and reached a peak in the 1970s. A flurry of experimentation occurred during this period, leading many agencies to dump the LRN bullets and replace them with hollowpoint designs. As part of this shift, the industry also moved to increase the MAP of the .38 Special, to boost bullet velocities and energy.

A new standard

In 1974, SAAMI adopted the use of the “+P” headstamp to denote a .38 Special cartridge with increased pressures. Manufacturers had been loading increased pressure loads prior to this, but it wasn’t until 1974 that the +P headstamp and pressure limits became an industry standard for commercial ammunition.

By this time, SAAMI had also adopted a new method of pressure testing, which would change the way that .38 Special +P pressures were measured and expressed.

With the development of the electronic transducer, a new method for measuring pressure was adopted by SAAMI, in preference to the copper crusher method. In the piezoelectric transducer system, a transducer is flush-mounted in the chamber wall of a test barrel, and when a cartridge is fired, the pressure acts on the transducer through the wall of the cartridge case, and deflects it. This deflection induces a current which is measured and converted into a pressure reading, expressed as pounds per square inch, or psi.

Therefore, when SAAMI published its standard for the .38 Special +P, it expressed it in two different values. Using the old copper crusher method, the .38 Special +P boosted the MAP from roughly 18,000 CUP to 21,900 CUP. Using the new piezoelectric transducer method, the .38 Special +P boosted the MAP from 17,000 psi to 20,000 psi. 5

The pressure increase resulted in velocities that were up to several hundred feet per second (fps) higher, with corresponding increases in muzzle energy. The extra energy boosted the effectiveness of the .38 Special +P loadings, especially when combined with better bullet designs.

Popular loads

The Winchester-developed, Saint Louis Police Department load, for example, was a completely different animal than the old 158 LRN. The Saint Louis load (introduced circa 1973, which still carries the Winchester product code “X38SPD,” today) combined a 158 grain, soft lead, semi-wadcutter-shaped, hollowpoint bullet (LSWCHP) with +P pressures (although the original loads were not labeled “+P,” since the new SAAMI designation didn’t take effect until the following year), to deliver a blow that was frequently credited with stopping criminals after one or two well-placed shots. This highly-effective load was used by other police agencies in cities as diverse as Chicago, Dallas (1973) and Miami, as well as by the FBI, who adopted it as their duty load in 1972. Both Remington (catalog number R38S12) and Federal (catalog number 38G) loaded their own versions of this cartridge as well.

Medium-weight, +P bullets were also popular in this era, and made by all the name brands, including Smith & Wesson, Federal, Remington (who introduced their 125 +P JHP in 1969) and Winchester, to name a few. Agencies all over the map, from Phoenix PD, to Baton Rouge PD, to the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, adopted 125 grain, +P loads for duty. 6 So did the Los Angeles Police Department, when it finally received its exceptionally-tardy permission to switch to hollowpoint ammunition in 1990. 7

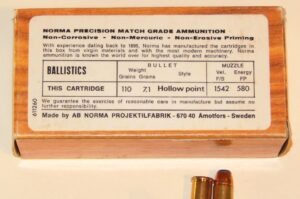

There were fans of the +P lightweights, too. Lee Jurras and SuperVel led the way, in this category, with their pioneering work on 110 grain jacketed softpoints (and later, hollowpoints) in the early 1960s, that were advertised to clock in the 1,300 fps range (but actually delivered closer to 1,100 fps in most guns—still a dramatic improvement, over the plodding, 158 grain loads of the era, at 750 fps, or so). The +P designator hadn’t been created yet, in these early days of hotrodding the .38 Special, so it didn’t show up on SuperVel packaging, but there’s no doubt the Shelbyville, IN, team was operating beyond normal .38 Special MAPs.

Later on, Remington’s 95 grain (catalog number R38S1, developed in 1972) and 110 grain (catalog number R38S10, developed in 1979) +P jacketed hollowpoints had their adherents, particularly among officers and agencies that carried smaller, snub revolvers. The same went for the equivalent products from S&W (who offered both 90 and 110 grain JHPs) and Winchester (who offered a 95 grain Silvertip JHP and a 110 grain JHP). The near-mythical Norma 110 grain JHP (catalog number 19119) was advertised at an amazing 1,542 fps in its earliest iterations (circa 1970), and was highly sought after by shooters who wanted the hottest .38 Special around. 8

The nation’s largest police department, the New York Police Department, was late to the +P game. In 1985, the 158 grain, .38 Special +P Federal Nyclad semiwadcutter (SWC) replaced the department’s standard pressure, 158 grain SWC (which had been in use since 1972) for duty. This nylon-coated, solid-nosed, semiwadcutter was issued in lieu of a hollowpoint bullet for political reasons, as civic leaders were afraid the public would protest their use. After the NYPD adopted autopistols in the early 1990s, and their 9mm full metal jacket (FMJ) loads proved unsatisfactory (due to their distressing tendency to overpenetrate and injure innocents), the department approved hollowpoint ammunition for use in all duty handguns starting in July of 1998. To outfit the majority of officers who still carried revolvers, the NYPD issued a 158 grain, +P Nyclad hollowpoint that remained in use in the Big Apple until the excellent .38 Special +P 135 grain Speer Gold Dot JHP load replaced it a few years later. 9

More Pressure

Savvy RevolverGuys will remember that the quest to squeeze additional performance out of the .38 Special didn’t end with the development of the +P loads. While the heavy (158 grain), medium (125 grain), and light (90, 95 and 110 grain) weight +P bullets appealed to some shooters and agencies, others thought the .38 Special could benefit from even more velocity.

We’ve previously chronicled the development of some of these high-speed, lightweight loads in detail, so it won’t be necessary to repeat that history now. For our purposes here, it’s simply important to note that the key to achieving the desired velocities was to increase the operating pressure of these loads even further. 10

While the SAAMI-spec, +P pressures could already drive bullets faster than their standard-pressure counterparts, the quest for maximum velocity led some users and manufacturers to experiment with pressures that exceeded SAAMI .38 Special +P levels. Since SAAMI would not adopt a specification for pressures beyond .38 Special +P, the individual manufacturers were forced to decide for themselves where they would cap the maximum pressure levels for this ammunition.

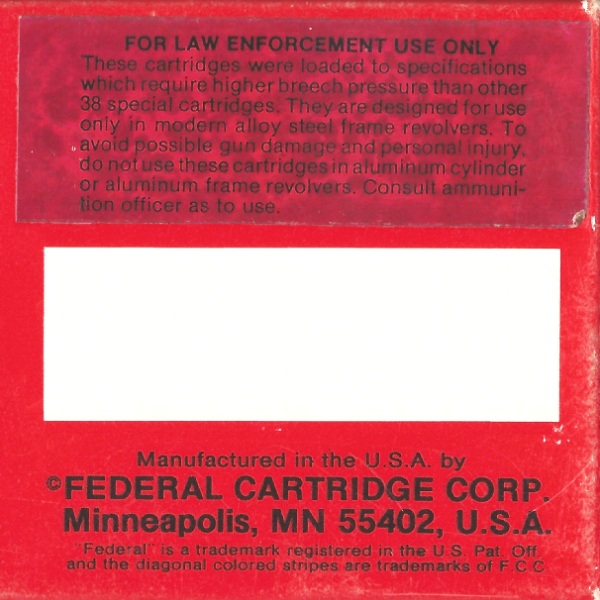

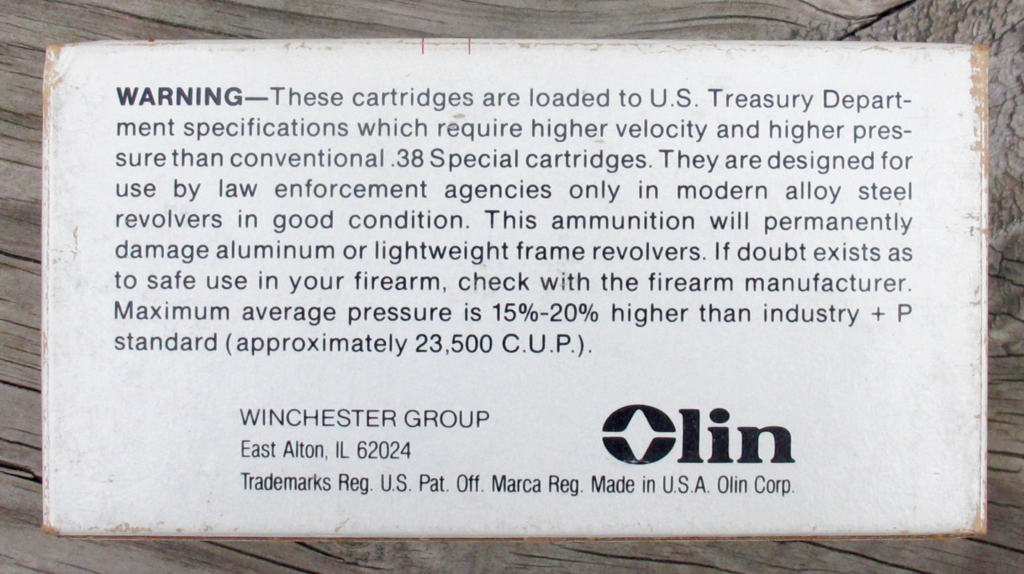

This non-SAAMI-spec ammunition was typically labeled “+P+,” to denote pressure levels that exceeded SAAMI +P standards, and every manufacturer had their own “recipe” for how much they would exceed the SAAMI standards. Winchester (who introduced their Law Enforcement-only +P+ round in 1974) loaded their +P+ ammunition to levels that exceeded the SAAMI +P spec (approximately 20,000 CUP) by about 15% to 20%, placing it around 23,500 CUP. 11 Federal (who introduced their Law Enforcement-only +P+ rounds in 1977) loaded theirs slightly milder. 12 Still other manufacturers ran theirs up to about 25,000 CUP—very close to .38 Special proof loads (28,000 CUP). 13

Most of the early +P+ ammunition development was focused on lightweight to medium weight bullets, in the 110 to 125 grain range.14 However, by the late 1980s, Federal was loading 147 grain bullets at +P+ pressures for the FBI, in an attempt to provide the Bureau’s revolver shooters a load that was ballistically equivalent to their 147 grain, 9mm auto duty load.

These +P+ loads were developed specifically for law enforcement, and manufacturers would not market or sell them to the general public. However, some of the ammunition managed to get into the commercial stream, via police officers or agencies who sold or gifted it, or dealers that didn’t abide by the manufacturer’s intent. 15

Problems

The arrival of .38 Special +P and .38 Special +P+ loads created some dilemmas for firearms manufacturers and shooters. While shooters wanted the extra performance promised by these hotter loads, many of the .38 Special revolvers in circulation weren’t sturdy enough to handle a steady diet of them.

Manufacturers knew that modern guns wouldn’t catastrophically fail, because they had been tested to proof levels beyond +P or +P+ pressures, but some of the older guns were more of a question mark. Additionally, even if the newer guns weren’t a failure risk, they would still get battered by the higher pressures, and parts would wear quickly. Endshake problems, timing problems, and even frame cracks or stretching were all possible outcomes of shooting the hotter loads in guns that were designed to shoot standard pressure loads.

So, manufacturers responded cautiously, and told shooters that they did not recommend shooting +P or +P+ ammunition in their guns chambered for .38 Special, and doing so would void the manufacturer’s warranty.

This was not the answer that shooters wanted, so many of them shot the hotter loads anyhow. Buoyed by the absence of catastrophic failures, they pressed the limits of endurance and learned the hard way that the manufacturers were right—the heavier loads eventually exacted a toll on the guns.

A new kind of pressure

Shooters—and particularly American shooters—always want more horsepower, so a delicate cat-and-mouse game developed, where shooters tried to press manufacturers into certifying their .38 Special-chambered guns for use with +P and +P+ ammo, and manufacturers resisted the effort as much as they could.

In the absence of solid guidance from the people who built them, shooters filled in the gaps with “rules of thumb” that spelled out which guns could handle the more powerful ammunition. Sometimes these “rules” were outright specious, and sometimes they were based on unofficial inputs from the manufacturers, but there was a lot of gray area to operate in, if you wanted to hot rod your .38.

Eventually, manufacturers were forced to break from their strict, prohibitionist stance, and/or their unofficial recommendations, and formally address the suitability of +P and +P+ ammunition use. In their earliest form, the factory-issued recommendations encouraged the use of standard ammunition as much as possible, but allowed shooters to use limited amounts of +P ammunition in certain guns. Additionally, the use of +P+ ammunition was generally prohibited, but manufacturers made an exception for law enforcement agencies that were willing to sign special letters of agreement that relieved the manufacturer from warranty claims.

1980’s Snapshot: Factory restrictions on the use of +P ammo

In 1986, respected gun writer Charlie Petty surveyed a number of manufacturers, under the auspices of the National Rifle Association, and asked them to publicly comment on their +P ammunition recommendations. 16 The result was the most comprehensive summary published to date, and included the following factory recommendations:

-

-

-

Charter Arms. Charter Arms did not recommend +P ammunition for use in any of its 5-shot revolvers (such as the Undercover or Off-Duty models), and recommended more frequent inspection intervals if it was used in the six-shot models;

-

Colt. Colt approved aluminum-frame guns (like the Agent and Cobra) for “limited use” with +P ammunition, and steel-frame models (like the Detective Special and Diamondback) for unrestricted use with +P, with the admonition that, “extensive use of +P .38 Special ammunition will accelerate wear in your revolver,” and the guns should be “checked at a Colt Authorized Repair Service Station periodically.” Colt’s recommended inspection intervals were every 1,000 rounds in aluminum frames, and every 2,000 to 3,000 rounds in steel frames. Colt would not approve the use of .38 Special +P+ ammunition in any D-frame revolver (essentially, any of their .38 Specials, including the steel-framed guns). Colt held that firing +P+ ammunition in a D-frame would damage the gun and void any of Colt’s service or warranty obligations;

-

Interarms. Interarms (the importers of the Rossi-brand revolvers, at the time) did not recommend the use of +P ammunition in any of their .38 Special revolvers;

-

Ruger. Ruger advised that their revolvers chambered for .38 Special were “suitable for unlimited use of +P and +P+ ammunition without restriction, provided such ammunition complies with the standards set for this ammunition by the industry.” Even then, Rugers were tanks!

-

Smith & Wesson. Smith & Wesson apparently delivered a two-page letter to Petty, which he distilled for readers. According to Petty, S&W advised that: The +P and +P+ loads should not be used in J or K-frame revolvers with aluminum frames, under any circumstances; Use of +P+ ammunition should be restricted to law enforcement agencies, only; The +P or +P+ ammunition could be used in J and K-frame revolvers with steel frames, and; Any use of +P or +P+ ammo should be minimized, since even minimal use would reduce the service life of the gun and possibly damage it. Smith & Wesson advised that revolvers fired with +P or +P+ ammunition “should be inspected for wear such as barrel erosion and cylinder endshake at intervals consistent with use of the weapon,” but did not define “minimal use” or establish clear inspection intervals as Colt thoughtfully did.

-

-

It should be noted that while Petty’s inquiry indicated that Ruger approved of “unlimited use” with +P+ ammunition, and Smith & Wesson approved of law enforcement agencies using it, neither of them marketed their firearms as being suitable for +P+ use. 17

Changes in the 1990s

These factory recommendations were constantly evolving, however, as were marketing practices, as the .38 Special +P became increasingly popular with the shooting public.

Whereas the major manufacturers had traditionally referred to the “.38 Special” chambering in their advertising and catalogs, by 1993 the cartridge was being referred to as the “.38 Special +P” in both Smith & Wesson and Ruger literature. Colt was an exception in this era (anyone surprised?), and continued to refer to it as the .38 Special, even when they announced the comeback of their D-Frame Detective Special in the supplement to their 1994 catalog.

The factory guidance on ammunition compatibility morphed as well during these years. By 1993, for example, Smith & Wesson had updated its Revolver Owner’s Manual to include the following new ammunition warning:

“Plus-P” ( +P ) ammunition generates pressures significantly in excess of the pressures associated with standard .38 Special ammunition. Such pressures may affect the wear characteristics or exceed the margin of safety built into many revolvers and could therefore be DANGEROUS.

“Plus-P” ( +P ) ammunition should not be used in medium (K frame) revolvers manufactured prior to 1958. Such pre-1958 medium (K frame) revolvers can be identified by the absence of a Model Number stamped inside the yoke cut of the frame . . .

. . . The “Plus-P-Plus” ( +P+ ) marking on ammunition merely designates that it exceeds established industry standards, but the designation does not represent defined pressure limits and therefore such ammunition may vary significantly as to the pressures generated. “Plus-P-Plus” ( +P+ ) ammunition is not recommended for use in Smith & Wesson revolvers. 18

Additionally, Colt updated their guidance to include a prohibition on the use of +P ammunition in D-Frame revolvers made prior to 1972 (models with an unshrouded ejector rod).

Where we are today

The .38 Special revolvers currently in production by firms such as Smith & Wesson, Colt and Ruger are all advertised and rated for the .38 Special +P, and you can fire this ammunition without undue concern.

Smith & Wesson, for example, clearly permits +P ammunition in their newly-manufactured guns chambered in .38 Special, but properly warns that it “may result in the need for more frequent service.” Colt permits .38 Special and .38 Special +P without further comment, and Ruger does too, but does add that you shouldn’t shoot “any other ammunition,” in a likely caution against +P+ ammo.

Of course, the guns chambered in .357 Magnum from these manufacturers are also cleared to shoot .38 Special +P ammunition, and while you won’t find a manufacturer that will publicly acknowledge the safety of firing non-SAAMI, .38 Special +P+ ammunition in their guns, the +P+ pressure limits which have been respected by the major manufacturers all fall below the SAAMI MAP standard for .357 Magnum, so there’s no safety concern, there.

So, should I shoot +P or +P+ in my .38 Special?

A budding RevolverGuy can easily get confused about whether or not it’s safe to shoot +P or +P+ ammo in their .38 Special revolver, particularly if it’s an older model. There’s no shortage of people ready to give you advice on this subject, but we urge you to be cautious and deliberate.

If you’ve purchased a newly-manufactured revolver, your first step is to check your owner’s manual, and see what the manufacturer says about the ammunition that is compatible with your gun. The same applies for older guns of recent manufacture (let’s arbitrarily define “recent” as manufactured in the last 10 years) that are still in production—consult the manual, or call the manufacturer’s customer service department with your serial number and make an inquiry.

Older, discontinued, or particularly valuable guns definitely require more caution. If you have the period-correct manual, it should be consulted. Additionally, it would be appropriate to call the manufacturer’s customer service department with your serial number and make an inquiry, since we’ve seen how the guidance from the manufacturers evolved over time. What is printed in your vintage manual may no longer represent the current best practice, based on what we’ve learned since then.

Even if the manufacturer gives you the go ahead, you may consider not loading an older gun with +P ammo. Shooting +P ammo in any gun, new or old, will accelerate wear. Since the supply of spare parts for the older guns (i.e., the pre-MIM S&Ws, or any of the old Colts) is rapidly dwindling, you could easily wind up breaking or wearing a part on your vintage gun that you just can’t replace anymore, if you shot a lot of +P ammo in it.

There’s little need to shoot +P ammunition for target practice or most sporting uses, anyhow—stick to the standard velocity fodder and save the expense and wear. For defense, we’d generally suggest taking it easy on the older guns (particularly any gun with an aluminum frame) and loading them with standard pressure ammunition, only. You can find several good standard pressure options (including wadcutters) out there for defensive loads, and don’t need to step up to +P pressures to get reasonable performance.

In some cases, it may be worthwhile to shoot a limited amount of +P ammunition in an older gun (for instance, it’s the only gun you have and you can’t afford a modern replacement, or the older gun is particularly suitable for your defensive mission), if you’re willing to have it inspected regularly for wear. Otherwise, we’d suggest staying with standard pressure loads.

If you want to shoot unlimited amounts of +P ammunition in your revolver, then you should buy a current production .38 Special that’s rated for it, or buy a .357 Magnum revolver, and load it with your .38 +P ammo. That’s the most conservative way to go, and one that will help to preserve the fine old guns for posterity.

It’s our recommendation to avoid shooting +P+ ammunition in your .38 Special revolvers, and reserve those loads for your .357 Magnum revolvers, instead. At the time those loads came on the scene in the 1970s, there was an arguable case that the +P+ pressures made sense, given the unsophisticated bullet technology of the era. However, that time is long past, and it is no longer necessary, or desired, to boost pressures beyond SAAMI-specs to obtain good performance from .38 Special ammunition. There are many excellent, +P-rated, .38 Special loads on the market (such as the Winchester Defender, Hornady Critical Defense, Federal Hydra-Shok Deep, Federal HST Micro, CorBon DPX, and Speer Gold Dot) which will do everything you can reasonably expect from this caliber, and it’s foolish to accelerate the wear and tear on your gun, regardless of vintage, by loading it with +P+ pressure ammo.

Enough!

That’s probably a much deeper dive into the .38 Special +P than you ever intended to take, but we hope you found it interesting and educational. If you still have questions about .38 Special +P or +P+ ammo, hit us up in the comments and we’ll use the collective power of the learned RevolverGuy audience to answer it for you.

Be safe out there!

*****

Endnotes

-

-

This is true if we limit the discussion to medium-frame guns, like the Smith & Wesson Hand Ejector. However, successful hot-rodding of the .38 Special did occur under the guise of the .38-44 High Velocity (HV) cartridge, which was introduced in 1930, to feed the large-frame, Smith & Wesson .38-44 Heavy Duty. The Heavy Duty was essentially a Model 1926 .44 Special that was chambered for .38 Special, and it allowed Remington and Winchester to load a much more powerful version of the .38 Special, for use in this gun only. Author John Taffin notes that the .38-44 HV ammunition from Remington launched a 158 grain, FMJ bullet at over 1,100 fps, in comparison to the normal 775 fps velocity obtained by the 158 grain, lead round nose (LRN) bullet of the .38 Special. Experimentation with the .38-44 HV by Major D.B. Wesson, Phil Sharpe and Elmer Keith led to the introduction of the .357 Magnum in 1935, which was also chambered in Smith & Wesson’s large frame. Reference: Big Bore Sixguns, by John Taffin, 1997;

-

-

-

The Maximum Average Pressure (MAP) for cartridges like the .38 Special, .38 Special +P, and .357 Magnum, as defined by SAAMI, have varied over the years, as SAAMI has made changes to their test protocol and published revisions to the standards.

-

In 1978, an article written by Dick Metcalf indicated that the .38 Special MAP was 18,000 CUP and the .38 Special proof load MAP was 28,000 CUP (as compared to the current, 2021 SAAMI standards of 17,000 CUP and 29,500 CUP, quoted in the body of this article).

However, in a 1986 article, Charlie Petty indicated that the .38 Special MAP was now 18,900 CUP, and the .38 Special proof load MAP was now 27,000 CUP.

In the 1980s, SAAMI changed the dimensions of the copper cylinder it was using in these tests to harmonize with European standards outlined by the Permanent International Commission for the Proof of Small Arms (C.I.P. –the equivalent of SAAMI in Europe). The older cylinders used by SAAMI measured .225” x .500” but the new, size “C” copper cylinders measured .225” x .400”.

Changing the cylinders resulted in a change in MAP values for tested cartridges. The MAP for the .38 Special eventually changed to 17,000 CUP (versus 18,000 quoted by Metcalf in 1978 and 18,900 quoted by Petty in 1986) when the cartridge was tested with the shorter copper crusher cylinder. The MAP for the .38 Special proof round, which the manufacturer uses to test and certify firearms, eventually changed to 29,500 CUP (versus 28,000 quoted by Metcalf in 1978 and 27,000 quoted by Petty in 1986), and the MAP for the .357 Magnum eventually changed to 45,000 CUP (versus 48,500 quoted by Petty in 1986). Great care must be used not to mix and match values from different eras, when referencing older publications or standards.

RevolverGuy would like to thank Ed Harris and Mark Humphreville for their assistance with deciphering the changes in SAAMI standards. Additionally, we would like to thank Holstory editor Craig Smith for providing a copy of the following articles, which were instrumental in helping to research old SAAMI standards:

“+P .38 Spl. Loads,“ by Charles E. Petty, which was published in the November 1986 edition of the American Rifleman magazine, courtesy of Craig Smith;

“Gun Manufacturers Issue Ammo Warnings,” by Dick Metcalf, which was published in the November 1978 edition of Shooting Times magazine, courtesy of Craig Smith;

-

-

Although a heavyweight, 200 grain, “Super Police” load had been flirted with, it was found to be unsatisfactory, and the 158 grain, lead round nose (LRN) cartridge was favored as the standard police issue round of the era. Despite its widespread adoption, the 158 LRN was also disappointing, and earned the sobriquet of “widow maker” from cops who were generally unimpressed with the terminal performance of the big, round slug.

-

This wasn’t a universal belief, however. Somewhere in the “files” (a generous description of the stacks of boxes in my office and garage) I have an article that was written by a police officer of the 1950s-1960s era, who opined the real problem with the 158 LRN was not the bullet, but the poor shooting of the officers who fired it. This writer said it was his experience that the 158 LRN did a reasonable job when placement was good, and it was unfair to blame the bullet for failures to instantly incapacitate an offender when peripheral hits were scored.

That’s ageless advice, and something we continue to struggle with today. Law enforcement gunfight hit ratios have never been very good, and there has always been a tendency to blame the equipment, instead of the shooter. If we peel the outer layers of the onion, past the stories of .40 S&W, .45 ACP, and 9mm “failures,” we’ll discover 158 LRN widow maker stories beneath. Same tune, different decade.

Judging the 158 LRN against the available technology of the time, it probably wasn’t a bad choice, as a general-issue round. It was controllable, accurate, offered sufficient penetration, and was easy to load into the chambers of a revolver from a dump pouch, loops, or (eventually) a speedloader. One could argue that semi-wadcutter or wadcutter designs may have performed better than the LRN bullet—and many cops did–but in an era of standard pressure, non-hollowpoint ammunition, the 158 LRN was probably as good a choice as any in the caliber.

If you wanted to improve terminal performance prior to the ammunition developments that occurred, beginning in the 1960s, the real answer was to step up to a .38-44 HV, .357 Magnum, .44 Special, or .45 Colt. These cartridges would deliver more of a punch, but this added performance came at the cost of increased recoil, and a larger, heavier gun weighing down your Sam Browne.

When Lee Jurras brought the first jacketed hollowpoints to market, under the SuperVel label, in the early-to-mid-1960s, the 158 LRN’s days were numbered. The new, high-velocity, hollowpoint designs raised the bar on what was possible with the .38 Special, and the weaknesses of the old 158 LRN became starker. After seeing what the new ammunition could do, cops were increasingly eager to ditch the antiquated 158 LRN;

-

-

The cry of the day was to denounce the “Vietnamization of Main Street,” which referred to the perceived “militarization” of civilian police forces in America. The spikes in political and criminal violence of the mid-1960s to the late-1970s encouraged many agencies to make changes in equipment, policies, training and tactics that were criticized by groups that were hostile to the police. For example, when the Los Angeles Police Department created the SWAT concept in 1966, they were accused of creating a military-like force to “wage war” with the city and “occupy” it like an enemy invasion force. Similarly, when the Connecticut State Police adopted .357 Magnum revolvers in 1973, it resulted in an outpouring of complaints about the powerful Magnum chambering. Public protests like these deprived officers in California, New York City and Boston from getting access to shotguns, as well;

-

The 1978 .38 Special MAP value of 18,000 CUP and the 1986 .38 Special +P value of 21,900 CUP are quoted. The psi values are from current SAAMI standards, and reflect a change from earlier values quoted by Federal’s Sheppard “Shep” Kelly, who fixed the .38 Special +P Maximum Product Average at 18,500 psi, circa 1992.

Reference: “What is +P+ Ammuntion?” by Sheppard Kelly, published in the September/October 1992 edition of Police Marksman magazine, courtesy of Craig Smith;

-

Author and Snub Gun Study Group co-founder Stephen Wenger still has a box of LASD-issue Remington 125 grain loads (the HI-SPEED, 125 grain, JHP load, Index 2038) in his possession from the era. While Remington did not attach a +P label to the HI-SPEED, Wenger notes that it definitely recoiled like a +P in the 4” S&W Model 15 revolvers issued by the department. The LASD would later replace the Remington HI-SPEED with the 110 grain +P+ Federal 38F-TD load (previously discussed HERE), but deputies of the era were permitted to use existing supplies of the 125 grain Remington load while they remained in stock. Deputies were also permitted (and informally encouraged by some trainers) to purchase their own 125 grain +P JHP loads, and use them for duty in lieu of the department-issued 110 grain load, so 125 grain loads were still encountered in department use through the transition to the 9mm Beretta 92F pistol. Incidentally, the LASD’s Policy & Procedure Manual called for the use of Remington’s 95 grain JHP load in the 2” backup revolvers carried by a large number of deputies.

-

RevolverGuy readers with a good memory will recall that LASD flirted with high-speed .38s even earlier than the period of the late 1970s to early 1990s described by Wenger. The agency was perhaps the first in the nation to contract with the then-fledgling, SuperVel company in 1967, for duty ammunition;

-

-

The Remington 125 grain +P S-JHP was issued by the LAPD, when they made the switch to hollowpoint ammunition, circa 1990. In the early 1970s, LAPD officers were issued Winchester 158 RNL (or occasionally Remington 158 RNL) and were also authorized to carry privately-purchased, Winchester 200 grain Lubaloy RNL. Those rounds were replaced by a 125 grain Federal jacketed soft point by the early 1980s, which served until the hollow points were authorized a decade later.

-

Reference: Interview with LAPD Capt (Ret.) Dick Bonneau. Thank you sir, for your help!

-

-

Author James R. Olt, writing in the 1971 Gun Digest, said that Norma introduced this hot load in their 1970 catalog, but he hadn’t seen any of it yet, at press time. Interestingly, the Swedes didn’t slap a +P label on this load, even though it was probably operating close to .38 Special proof-level pressures to generate that kind of velocity! The 1,542 fps advertised velocity was probably achieved from an unvented test barrel, but when Evan Marshall tested the loads in real guns, he still achieved an impressive 1,120 fps out of the 2” barrel of a Colt Detective Special, and 1,312 fps out of the 4” barrel of a S&W Model 66, which placed this load at the top of the heap–even above the hot SuperVel load of the era.

-

By 1980, Norma had rechristened the load as the “.38 Special Magnum,” and added a +P label to the box. This newest version, which retained the same 19119 catalog number, was advertised at “only” 1,225 fps, which seems to indicate that Norma had made a conscious decision to align with SAAMI standards, and realized that the pressures were unacceptably high in the original formula.

Reference: “The .38 Special,” by James R. Olt, in the 1971 Gun Digest, and “Viewing the Ammo Scene,” by Evan Marshall, printed in the January/February 1978 edition of American Handgunner magazine, and Norma advertisements (1973 and 1981), courtesy of Craig Smith. Thank you Craig, for all the wonderful documentation you provided!

-

-

The 9mm +P Speer 124 grain Gold Dot, which was fielded in March 1999, achieved such a wonderful track record in NYPD autos that the agency requested Speer to develop a .38 Special load for the 2” and 4” revolvers that were still in widespread use at the agency. Speer’s answer was the .38 Special +P 135 grain Gold Dot, which came aboard in the early 2000s (after 2002), and soon developed an enviable reputation for performance that made it one of the most respected loads in the caliber.

-

Reference: “Why the NYPD Changed to Hollowpoints,” by Ed Sanow, published in the 2002 Handguns Annual

-

-

Much of this push came from the Treasury Department, who wanted a load that delivered lots of energy, but had reduced potential for overpenetration. The original Treasury Department requirement called for a .38 Special load that would generate 1,020 fps from a 2” S&W Model 15, which was their duty gun at the time.

-

Reference: “Gun Manufacturers Issue Ammo Warnings,” by Dick Metcalf, which was published in the November 1978 edition of Shooting Times magazine

-

-

Winchester’s Q4070 “Treasury Load” was a 110 grain JHP at +P+ pressures. Winchester’s packaging claimed an average of 23,500 CUP, compared to the 1978 SAAMI .38 Special +P standard of 20,000 CUP. Note that Copper Units of Pressure (CUP) is not a linear measurement (so 10 CUP is not 10% of 100 CUP), which is how 23,500 CUP could represent a 15% to 20% increase over 20,000 CUP. As Ed Harris explains, once the compressive strength yield point of the copper is reached, the rate of deformation is no longer uniform. Instead, once the material starts to yield, the rate at which it deforms rapidly increases, and the CUP measurements reflect this by being non-linear units of measure.

-

Reference: “+P .38 Spl. Loads,“ by Charles E. Petty, published in the November 1986 edition of the American Rifleman magazine, courtesy of Craig Smith.

-

- Federal probably worked in the vicinity of Winchester’s 23,500 CUP for their 110 grain, +P+ 38F-TD load, but in the author’s personal experience (shooting CHP-issued ammunition from both makes), the 38F-TD load was never as brisk as the Q4070, and it’s suspected that the +P+ MAP was slightly lower at Federal.

Stephen Wenger reports some Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department deputies noted a 100 fps decrease in their Federal 38F-TD ammunition over time, which they speculated was at the department’s request, to avoid warranty issues with Smith & Wesson. This reduced-velocity version was still labeled the same on the box (which, curiously, never included a “+P+” label, only a “Law Enforcement Only” label, and a warning on the back that the ammunition generated “higher breech pressure than other .38 Special cartridges”) even though it no longer seemed to be loaded as hot as the original 38F-TD loading.

In a 1992 Police Marksman article, Federal’s Shep Kelly stated their .38 Special +P+ ammunition was loaded to 22,800 psi (vice 18,500 psi for .38 Special +P and 28,000-38,500 psi for .38 Special +P Proof loads). It’s not clear how this compares to Winchester’s 23,500 CUP, due to the different units, but again, the author’s experience has been that the Federal Cartridge Company ammunition was loaded lighter than the Winchester product.

Reference: “Dope Bag Q&A,” by William C. Davis, Jr., published in the March 1979 edition of the American Rifleman magazine, courtesy of Craig Smith.

Reference: “What is +P+ Ammuntion?” by Sheppard Kelly, published in the September/October 1992 edition of Police Marksman magazine, courtesy of Craig Smith;

-

-

By the late 1980s, CorBon was loading a 115 grain Sierra JHP at +P+ pressures as well, which they would later change to a 110 grain JHP that was originally advertised at 1,300 fps, then later adjusted to 1,250 fps:

-

CorBon did not abide by SAAMI standards in the early years, and their .38 Special +P+ loads were demonstrably hotter than the Winchester and Federal products. Gun writer Charlie Petty believed they were loading their product to pressures in the neighborhood of 25,000 CUP or more, which technically overlapped the low end of .38 Special proof loads. The proof loads started around 24,000 CUP and had a MAP of 28,000 CUP in 1978 (27,000 CUP in 1986).

Reference: “+P .38 Spl. Loads,“ by Charles E. Petty, which was published in the November 1986 edition of the American Rifleman magazine

-

-

With the research assistance of Holstory editor Craig Smith, we’ve been able to determine that Federal loaded three different types of +P+ ammunition during this period: First, a 110 grain JHP which was loaded for the Treasury contract (catalog number 38F – TD), and also used by agencies like the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and California Highway Patrol; Second, a 125 grain, jacketed softpoint load developed for the Michigan State Police (catalog number 38J-MI), and; Third, a 125 grain, jacketed hollowpoint load (catalog number 38E-IL) developed for the revolver-armed agents of the former Illinois Bureau of Investigation, which had, by this time, been merged into the Illinois State Police.

-

-

Some of the early SuperVel ammunition definitely strayed into +P+ territory, but the company went out of business by the time the +P+ designation was standardized by the industry. It wasn’t until the advent of Peter Pi’s CorBon that the average consumer could purchase +P+ ammunition through normal, commercial channels. The short-lived Triton ammunition company, which loaded Tom Burczynski’s Quik-Shock bullets, also tried to compete for some of this +P+ business in the late 1980s and early 1990s;

-

-

-

Reference: “+P .38 Spl. Loads,“by Charles E. Petty, which was published in the November 1986 edition of the American Rifleman magazine, courtesy of Craig Smith;

-

-

-

In the 1970s and 1980s, manufacturers like Smith & Wesson required agencies to sign waiver agreements if they intended to shoot +P+ ammunition, which absolved the manufacturer of liability and warranty obligations. These “proceed at your own risk” agreements were never extended to individual officers (including those who were required by agency policy to purchase their own weapons), only to the agencies themselves. Nor were they offered to the public. Similar agreements were imposed by Winchester, who required agencies to certify that the +P+ ammunition would only be used in “firearms of modern design,” and would not be used in firearms with aluminum alloy frames;

-

-

-

The +P+ warning is especially notable here, in light of the 1989 introduction of the Model 640 Centennial revolver, which was initially marked “Tested For +P+” on the frame:

-

Early S&W Model 640 with “TESTED FOR +P+” marking on the frame. Image courtesy of RevolverGuy Dean Caputo. This was a first for the industry, and it didn’t last long. Since there was no SAAMI standard for +P+, and some non-SAAMI manufacturers were actually pushing the boundaries of Proof Loads with their +P+ loadings, a marking like this was the equivalent of writing a blank check. The unique marking quickly disappeared from the Model 640, likely at the bequest of the Legal Department in Springfield, and the gun was thereafter referred to as a .38 +P-rated gun. The misstep is probably what generated the new warning in the Owner’s Manual.

-

Ruger: “Doesn’t matter. Run whatever you want in our wheelguns – they can take it. ”

THIS is why I love Ruger. 😉

I got a grin out of that response from them, too!

Yep. My Blackhawks are where I test new loads before trying them in other guns.

This is what makes Rugers my revolvers. I have owned S&W, Taurus, shot a Colt, handled others….and nothing does what my Rugers can do for me.

Just my personal note, nothing more.

Thank you.

About time the .38 Special receives the

attention it deserves.

In the age old caliber wars debates, the

.38 often was the poor old dog that

no one considered very good–at any time.

Again, thank you for a very, very needed

article on a caliber that still fills the chambers

of many self defense guns throughout the

so-called civilian population. It’s a caliber

that most can handle with minimal practice

and provide adequate to excellent results.

This article and the valuable followup notes

comes at a time when members of The High

Road forum have been extensively discussing

the .38 are a service revolver round.

Thanks Ed! Invite them to come on over, read the article, and let us know their thoughts in the comments.

It’s inefficient, as a result of its blackpowder-volume case, but I’ve always loved the .38 Special—it’s my favorite revolver caliber.

take a look at Federal HST .38 Special +P

Superb article. The .38 Special gets my attention faster than any other cartridge around. One can only wonder what ammunition development would have been had the .38 Special been introduced originally as a smokeless powder round. Safe to say that its potential in 1900 would have far outstripped the metallurgy and heat treating of the day.

There was probably more experimentation, reasearch and development going on during the 1960s to 1990s for the .38 Special than for any other handgun cartridge around, including the 9m/m Luger.

I do have a precious box remaining of Remington .38 Special 125 grain JHP headstamped ” R-P .38 Spl HV “. Several municipal departments in central Florida issued that for their 38 revolvers. It was a fire breather out of my issued .357, with muzzle velocities well over 1200 fps. Easily put the .38 Special in 9m/m territory. I carried some of those HV rounds in my backup M36, although I was probably smart enough not to shoot any of it out of that gun. Also have two full boxes of Federal 158 LSWCHP +P Nyclads. Those were a handful in a steel J-frame.

Thank you Sir! I appreciate the reference to the Remington HV load, as it helps to reinforce the pattern that Remington was loading a lot of +P-territory ammo before they ever adopted the +P headstamp.

I agree—it’s fun to speculate how the .38 Special might have evolved, if it hadn’t started as a blackpowder cartridge!

It seems as though often the quest for hotter and hotter ammo is based on too many gun owners’ poor marksmanship. Their comments on the subject suggest a Holy Grail belief that higher velocity rounds will make up for their incompetence. In fact, those loads most likely will only worsen accuracy for poor shooters because of increased recoil.

Thanks for a deep look at a faithful old friend, Mike. Not a 9mm, not a .357 Magnum, but a worthwhile round that has defended around the world for over a century.

Absolutely, DB. It was a labor of love. I’m very fond of the .38, despite its flaws! My wife says the same about me. ; ^ )

Thank you for the research you do and an excellent article to read. As a senior citizen shooting a K frame double action I’m not ashamed to say I stay away from +p ammunition for accuracy reasons.

No shame in that, Steve. That’s why I generally avoid the hard-kicking stuff, myself. A well-placed wadcutter from your .38 Spl will do the job nicely. That’s one of the beauties of the .38 Spl and the revolver in general—being able to choose from different power levels in the same cartridge.

One issue I didn’t see addressed in the article is that fixed sight 38 revolvers were regulated for the 158 grain service loads. Happily the 148 grain midrange and usually the 158 grain lead SWCHP +P strike point aim point of impact at useful ranges too. The lighter, faster loads strike low, sometimes significantly, even at conversational distances. While this would be of no concern to a shooter in 1970-80s running a S&W M15 or M19, it can be a detriment to precision to the fella shooting a S&W J-frame.

Agreed. I’ve discussed that at length in many other articles here on the site (including our articles on sight regulation and point of impact, and snub ammo testing, links below), so I didn’t dive into it here, as I was already “trying to cram ten pounds of stuff, into a five pound bag,” as my dad used to say. ; ^ )

It’s a very important consideration, though. I was a fan of the high speed lightweights for a long time, but was always unsatisfied with the sight regulation issues, which is what led me to the 130-135 grain bullet weights that I now prefer, as they print much closer to my 640’s sights.

The Kimber K6s revolvers I’ve been playing with and writing about have been particularly sensitive in that regard.

https://revolverguy.com/sight-regulation-and-point-of-impact/

https://revolverguy.com/38-snubby-ammo/

Thanks Mike. BTW You did a fine job of fitting all ten pounds into the five pound can. Not surprising as that’s how you roll. Keep ‘em coming!

Why did you do this to me! I started my Colt Cobra on wadcutters. They did seem up to the task of possible self defense since it was only a practice round. Then I began the search for the best possible standard pressure round. Ranging from silvertips to nyclads to gold dots. After reviewing any data I can get my hands on I have returned to the lowly wadcutter for defense. Its very controllable in a small handgun for my wife. No recoil so she can keep her shots all on a torso sized target. And as a bonus little wear on her classic revolver! But great article!

Side note; I have my uncles footlocker full of some of the exact ammo you mention above as he was in the California highway patrol. He primarily shot and carried +P while practicing with box after box of wadcutters. He only had two speedloaders full of 357 in all his duty gear. Interestingly his backup was an early no dash long extractor Smith model 39 that he carried in his riding boot (he rode motors to retirement) that was loaded with supervel ammo!

Glad you enjoyed it, Bill! I think the wadcutter is a great choice, and if you haven’t seen our article on using them for self defense, I’d recommend taking a look:

https://revolverguy.com/wadcutters-for-self-defense/

I chronicled the history of CHP ammo in my book, and also touched on parts of it in my article on the Treasury Load:

https://revolverguy.com/ammo-evolution-38-special-treasury-load/

Without going into too much detail, the CHP only issued .357 Magnum ammo for a very brief time in the late 1980s. In the early days, many CHP officers purchased their own .357 Magnum ammo and carried it on duty (in preference to the state-issued, 158 LRN .38 Special), but that was always at their own expense, and the practice was eventually prohibited by regulation when the CHP adopted the .38 Special +P+ Q4070 “Treasury Load” circa 1976. That +P+ load became the exclusive, authorized duty ammo for CHP (except for a few weapon field test programs in the 80s) until about 1988 or so, when the CHP had a short-lived program that allowed officers to qualify with department-issued, .357 Magnum ammo and carry it on duty in their privately-purchased revolvers. The .357 program died when the CHP adopted the .40 S&W in 1990.

Now, a lot of savvy CHP officers carried unauthorized backup guns, in a wide variety of shapes, sizes, and calibers, but that was always a question of balancing risks—survival versus legal/admin. Sounds like your Uncle figured it out, with his SV-stoked, Model 39!

After reading your response I wonder if he started carrying 357 after the Valencia shoot out. I dont know what the CHP purchased but he did carry a private purchase 6″ Python.

Thanks a lot for the terrific article. That was informative and interesting. I am a huge revolver fan and appreciate your work.

Mike N.

Thank you Sir! Much appreciated! Glad you’re enjoying the site.

Outstanding article Sir!! It seems that everytime I start to research something wheelgun related, you post an article on the very stuff I was digging for. While my carry load in my Smith and Wesson M15 is the 158gr LSWCHP +P, I carry standard pressure 158gr lead semi wadcutter in my 442 and M36. There have been times in my life, I convinced myself I was undergunned unless I had a 357 magnum however I have learned the 38 special is more than capable for everything I need. Thank you again for your informative and entertaining articles.

Johnny Carson taught me his mind-reading trick, Mark. I bet, this very moment, you’re thinking about where you can find some .38s, right? See? It works! ; ^ )

Glad you’re enjoying it so much and appreciate you and the others letting me know. It’s a lot of work, but you guys keep me motivated to stick with it, with your kind praise. We’ve got more good stuff on the way, so stay tuned and tell your friends.

By the way, standard pressure SWCs are a great choice for that snub. Well done.

To call this article comprehensive would be the understatement of the century. This was a fantastic read, and I loved Ruger’s comparatively brash confidence in their guns’ ability to handle +P.

Great stuff, as always. Thank you. Hope you don’t mind my linking this piece on the Snub Noir facebook page. A whole bunch of .38 Special guys over there.

Thanks Bill. We’d be happy for you to share it with the gang over there. Glad you enjoyed it.

Great article.

I’m currently working on finding a load with 147gr G2s. Right now I’ve topped out at 920fps in 4″ guns but would like to hit 1k so I can get 900fps from 2″ guns.

AA9 here I come.

Untill then I’m perfectly happy with 158gr swc @ 950 fps.

Ryan, are you pulling the G2 bullets from Speer 9mm cartridges?

I was disappointed in the G2 bullet when I tested it in calibrated ballistic gelatin a few years back. Some projectiles didn’t expand at all, and some barely opened up. It was very inconsistent, compared to other bullet designs. I’d rather use the regular Gold Dot bullet, myself, because it’s a consistently strong performer.

I’m surprised to hear that! My agency switched to 9mm 147 G2, I guess because (at the time) FBI. We find them excellent performers on all perps.

I’m glad they’re working well for you guys, Riley. Nothing beats real-world experience. Keep up the good work.

I think the Feebs quietly walked away from that round. I don’t believe it’s standard issue for them any longer.

I think they went to Hornady Critical Duty 135 +p.

Yep

They were pulls sold by American Reloading. For a price that I don’t mind using them as plinking ammo.

I think the G2s had 2 iterations to acknowledge that inconsistent expansion.

I think I’ll pick up some 147 HST pulls next time they pop up as I trust them to open up at a little slower velocity.

Bravo! Outstanding as usual. As I age I’ve come to appreciate the simplicity and reliability of a good, high quality wheel gun. My LCR is my go to EDC. As I might have mentioned, I am fond of Federal HST Micro 130 gr. +P. Thanks again. Good read!

Thank you sir! An LCR with HST sounds like a wonderful combo. Be safe out there!

I’ve never encountered +P+ .38 Special myself, nor have I shot any.

I find that I’ve gotten good accuracy (by my standards, mind you) with bullets in the 125-130gr range. Federal’s 130gr+P HST and Steinel’s 125gr+P have largely shot dead on when I’ve tried them in my two carry guns (642 and Model 12).

110gr works too, but interestingly enough, only in standard pressure. Hornady’s 110gr CD has given me better accuracy than the +P version, and Winchester’s 110gr Silvertips give me similar results.

If I was carrying one of my Model 10s, any of those would do. But for my alloy-framed snubs, I do prefer something less spicy like the aforementioned 110gr loads partnered with the Federal HST. Steinel’s .38 Special load, as well as Super Vel’s 110gr+P load, can be a bear at times. And don’t even get me started on stuff like Underwood! Ouch!

Axel, I hadn’t heard of Steinel prior to your mention of it. I just checked out the website and REALLY like what those guys are doing, paying attention to overlooked and discontinued calibers. Their .44 Special loads look like they would be just the ticket in one of the 3” GP100s that Ruger sadly discontinued. I’m sure their .38/125+P would be a solid performer. Thanks for introducing me to them!

That SuperVel 90 grain .38+P (I think you meant 90, not 110?) is indeed a hot number. The projectile is a little light for my tastes, but it will certainly do a good job if you don’t have to penetrate too deeply, like on a frontal shot, with no intermediate barriers. I think I’d be happier with one of the 125-130 grain bullets you mentioned, FWIW.

Oops! Yes, my mistake, Super Vel’s load is a 90gr bullet as you said. Geez, go almost two years now without shooting any .38 Special and I guess I start getting my ammo mixed up.

Haha! I know what you mean.

What an excellent deep dive into a caliber I greatly enjoy loading and shooting. Many thanks!

FWIW, our .357s in the night stand load .38 +p, and we get a bit of range time annually with these loads, though mostly we train with standard-pressure .38s

.pWith +p rounds I do not feel under-gunned.

Thanks Wheelgunner! I agree—you’re not undergunned with a good revolver stoked with .38+P. That’s what defends my home, as well.

Great article!

Thanks!

May I link to a police site, with a lot of old time .38 guys?

Absolutely! Send ‘em over. The K9s too. We love our dogs here!

You must have been an arson investigator with that handle. I got a chuckle from it.

I stand corrected! I just learned your handle is slang for a railroad detective. You learn something new every day!

Great article! I love this website, it is a real service to those of us that still believe in and carry revolvers. I remember back in the 1980s when federal nyclad came out it was marketed as being easier on the bores of guns because it would not leave lead residue, but a side benefit was it also penetrated better also. Is my memory correct on this?

Hi Fastmike! I’m glad you found us and are enjoying the articles.

Your memory of the Nyclad is mostly correct, but needs some of the blanks filled in. Let me give it a go.

The Nyclad was developed by Smith & Wesson as a training load, when they were still loading ammo. The name springs from the bullet being nylon-clad (coated). In construction, the bullet was a soft lead slug that had a plastic-nylon coating applied to it.

The coating was primarily there to prevent airborne lead, as a health and safety measure for indoor ranges. When you fire a lead bullet, some of that lead gets vaporized by the extreme pressures and temperatures, and the Nyclad was an attempt to eliminate that, particularly for police agencies that did a large volume of training on indoor ranges, but also for commercial applications, as well.

The coating provided several other benefits. Because it lubricated the bullet, it was unnecessary to apply a wax coating to the lead slug (or a copper jacket). This eliminated the smoke that you get from shooting a waxed bullet, which can build up quickly on an indoor range, especially with a lot of shooters firing at once. The coating also eliminated the copper-lead smears that you had to clean out of your bore, after firing–it was much easier to clean out the nylon residue.

Interestingly, one of the principal benefits of the coating wasn’t recognized, at first. The coating allowed S&W to use soft lead bullets, and skip the time and expense of hardening them, because the lead didn’t come in contact with the bore. This made the bullets more economical to produce, as target loads. However, the soft lead core was soon recognized to provide another advantage–the bullets readily deformed, even at low velocities. It soon became apparent this characteristic could make the Nyclad a good defensive bullet, as well.

With the bullet technology of the era, bullet expansion could be unreliable, especially with moderate cartridges like the .38 Special, which didn’t produce a lot of energy. The softer lead of the Nyclad bullet made it more ductile though, and a reliable expander, even at standard pressures and velocities, so interest in the Nyclad as a self-defense bullet grew.

Both hollowpoint and +P versions of the Nyclad were introduced. The +P versions likely started as an effort to provide police departments a training load that was a ballistic match for the traditional, +P hollowpoint loads they were carrying on duty, but some departments (like NYPD) carried the +P SWC (non-hollowpoint) version of the Nyclad as a duty round, because they were restricted to solid-nose ammo by city leaders (the NYPD later got approval to carry hollow points, and switched to a +P hollowpoint version of the Nyclad).

One of the sweet spots for the Nyclad was the standard pressure, .38 Special hollowpoint. This round was suitable for use in the snub .38s of the era which were not rated for +P pressures. It was also favored by users who didn’t want a lot of recoil in their snubs. The soft Nyclad bullet still did a good job of expanding at the lower velocity it attained from these snubs, and developed quite a following.

When S&W got out of the ammo business, Federal picked up the rights to the Nyclad and produced it for many years. It was really during the Federal era that the Nyclad developed into a defensive round, and what basically killed it was the rise of the Hydra-Shok bullet, as Federal’s premium defensive round. The coating process was also more difficult and expensive than desired (today’s Syntech process is much better, due to advances in tech over the course of several decades).

The Nyclad made a short appearance back in the Federal catalog in the early 2000s, in standard pressure, .38 Special 125 grain guise, but it didn’t last long. You can see how that ammo performs in gelatin by checking out our article on snubby ammo, here: https://revolverguy.com/38-snubby-ammo/

I hope that helps to fill in the gaps!

Thanks Mike, for putting out the excellent info on +P, +P+, and this P.S. on Nyclad ammo. I need to add that to my Christmas wish list; when S&W re-issues the Model 12- a Nyclad 158 SWC HP non +P for a duty load and a Nyclad 158 SWC for an accompanying practice load. 🙂

Consider it officially amended, Kevin!

Well, heck. Since the comments have turned into a short course on the Nyclad, a RevolverGuy friend has suggested that I should share another tidbit about the round, so here it goes. It seems his agency had issues with a ring of the nylon coating getting scrubbed from each bullet and collecting at the forward part of the chamber on their Beretta 92 pistols (9mm 124 grain Nyclad). Over time, enough of the material would build up that a cartridge would not fully chamber, due to insufficient headspace, and the slide would not go fully into battery. A robust cleaning would resolve the issue, but the problem eventually forced a switch to the excellent Federal 9BPLE at his agency.

Whew! What were we talking about again? Oh yeah, .38+Ps!

Fastmike,

Mike gives a great history for Nyclad, but I’ll add this: in the ’80s and ’90s, when jhp bullets were shot through sheet metal (cough, car doors, cough) they would tend to lose their jackets and were then not such hot performers… Nyclads had no jacket to lose, and tended to work better when shooting through obstacles at bad guys.

Yes, absolutely, windshields too. Thanks for the backup, Riley!

If I remember correctly (that’s a big “if” these days), the Nyclad round was eventually discontinued for two reasons, one sorta substantive and the other political BS. The first was that the original nylon cladding was flexible and would reform after shooting enough to change the rifling marks on the bullet, so it wouldn’t “pass” a ballistics test. I read that this problem was eliminated by using a thinner nylon cladding with less “give” to it. The second reason was the “Teflon cop-killer bullet” hysteria in the 80s. The press, ever eager to spread antigun ignorance, claimed that police officers were being murdered with “Teflon” bullets that would penetrate a vest. Even though no cop was ever killed with a “Teflon” bullet, the blue nylon coating on the Nyclad caused it to be banned in several jurisdictions (even though it was issued in other places, including NYPD), and Federal decided it wasn’t worth the hassle.

Thanks 1811!

I’ve heard similar complaints from both coasts about the rifling issue, with examiners in LA and NY being unhappy they could not identify which firearm a given bullet was fired in, due to the coating, but I had no evidence that these concerns influenced Federal’s decision to discontinue the round, so I didn’t discuss that. There may be something to it, but I can’t verify.

I hadn’t remembered the Nyclad being associated with KTW, but there might be something to that, too—my memory ain’t what it used to be, either!

Thanks again for the extra info.

Revolverguy,

I noticed the link for Ed Harris didn’t work for me.

Try https://sites.google.com/view/44winchester/chasing-the-44-40/contributors/ed-harris

Thanks Bryan. That’s the link I was using, not sure why it didn’t load. I went back and renewed it. Looks like it’s working OK now. Appreciate it!

Great article! This is one of those historical articles that I know is accurate because I was there for it.

When I became a police officer in the late 80’s if you had an “air weight” you were supposed to carry and, after we started issuing ammo, were issued non +p nyclad ammo. A few years into my career, after a qualification, I was handed some +p’s. I told the guy at the range he gave me the wrong ammo. He told me that it was ok because Smith and Wesson sent the rangemaster a letter that said +p’s were ok in air weights. Nothing changed except that sergeant had a letter. That department has issued +p’s ever since.

Keep up the good work.

Thanks BC! We pride ourselves on accuracy, here, and always appreciate outside confirmation that our info is solid. There’s so many places on the interwebs that are, shall we say, less particular about getting the facts straight!

Be safe!

It’s truly a relief and benefit to (as well as more enjoyable for) me that Revolverguy prides itself in producing accurate, trustworthy information. So many internet sites could care less. Appreciate your hard work and attention to detail.

Thanks for article.

I enlisted in the USAF in 1983 as Security Police Law Enforcement Specialist. At that time we carried the S&W M15 Combat Master Piece. We were told the .38 ammo issued to us was +P+. I can’t really remember looking at the head stamp. I heard a lot of talk about how the .38 wouldn’t stop anybody and bounce off a tire, but working with the Polizei they liked out .38s over their sidearms.

Hi Alan! Great to hear from another airman. The M15 is what I qualified on, when I entered the AF as well. I keep hoping the CMP will find and sell those someday (what happened to all of them? Where did they go?).

The duty ammo you’re referring to was the USAF PGU-12/B High Velocity cartridge, which was a much hotter number than the M41 ball that the rest of the services issued.

The M41 ball was developed around 1956, in response to cracking issues in the USAF M13 “Aircrewman” revolvers, which had aluminum cylinders. The 158 grain military ball that had been in use since WWII was breaking those guns, and it was hoped the M41 (which launched a 130 grain FMJ at 720 fps from a 2” barrel) would be gentler on them. It did shoot softer, but the aluminum cylinders continued to break and the USAF replaced the guns with M15s (and the 2” version, called the M56).

The M15s were tougher guns, and could handle more potent loads than the M41, so the USAF developed the PGU-12/B cartridge that you remember. The PGU-12/B was unique looking, because the bullet was seated deep in the case. This, combined with a cannelure in the case, and a tight roll crimp, increased pressures to 20,000 psi (the same as the current SAAMI MAP for .38+P), and its 130-grain FMJ bullet did about 950-980 fps from the M15s.

There wouldn’t have been a +P or +P+ headstamp on any of those, because military cartridges don’t use that convention. They usually just use the name of the manufacturer and the year of production (i.e., “WCC 85” for Winchester Cartridge Corporation, 1985).

The USAF continued to issue M41 for some training, and for use in some of the J-Frames carried by OSI, but the Security Police definitely got the PGU-12/B for duty use.

“. . . in response to cracking issues in the USAF M13 “Aircrewman” revolvers, which had aluminum cylinders.” Was “M13” the USAF designation? Because the Smith revolvers with aluminum cylinders were Model 12s, not 13s. The Model 13 is the 80s-era .357 M&P.

Please clarify. Thank you.

(I’ve enjoyed your many articles on the Model 12, by the way, even though I’ve never actually seen one. As far as I know, they may be imaginary.)

Yessir, that was the USAF designation, not to be confused with the later S&W Model 13 in .357 Magnum. “Revolver, Lightweight, Caliber .38, M-13.” The guns were six-shot, K-Frames with aluminum frames and cylinders, and two-inch barrels. They were marked, “Revolver, Lightweight, M13” on the topstrap, and “Property of U.S. Air Force” on the backstrap.

They didn’t last long before it became apparent the aluminum cylinders were a bad idea.

A commercial version of the M13, with the same aluminum cylinder, was marketed as the M&P Airweight, but its lifespan was even shorter than the military’s gun (only lasting a year). Smith & Wesson wisely changed it to a steel cylinder in 1954. When the revolvers all received model numbers in 1957, it became the Model 12. So, technically, there are no Model 12s with aluminum cylinders, only some early, pre-Model 12, M&P Airweights.

Kevin sure did a nice job on our Model 12 article, and we were glad to run it. I’ve only seen one of those in the flesh, and have not fired one, but I’m sold on the idea of an Airweight K-Frame, and wish S&W would build one again (minus the lock, please—that’s an even worse idea than an aluminum cylinder, if you ask me).

Thank you. I learned something today, so now I can go back to bed.

I agree with you on the idea of bringing back the Model 12. I’d like to see a lightweight K-frame revolver, and with modern metallurgy it could easily (I’m guessing) be made to handle +P ammunition. (We can dream, right?)

As a retired NYPD officer I really appreciate your thorough research and excellent writing about the .38 / .38 +P rounds. This reads like a college course on ballistics, so I’ll have to review this wealth of information a few more times.

In the mid 1980s I recall an older sergeant being less than thrilled when NYPD bumped up our 158 grain LSWC from standard pressure ammo to +P. The aluminum S&W that he carried for 20+ years was no longer authorized for back up or off duty carry.

We were only allowed to carry 12 spare rounds in leather dump pouches. Speed loaders were forbidden. They were only authorized after P.O. Scott Gadell paid the ultimate price in 1986.

Hopefully his sacrifice saved the lives of his fellow officers by prompting a change in obsolete and draconian department policy.

May he Rest In Peace.

Upon my retirement I had to buy my own ammo. I recall buying a box of .38 +P Nyclad hollow points to load up my Model 10 and 36, plus a pair of speed loaders.

Thank you Sir, and welcome aboard! I appreciate the extra information you provided about the duty loads and department policies of the era!

It has always bothered me that NYPD was so late to approve speedloaders. The Left Coast agencies had already flocked to them, en masse, over 15 years before Gadell’s murder. Closer to home, the murder of NJSP Trooper Philip Lamonaco, under similar circumstances (emptied his revolver, was killed while trying to reload by a criminal/terrorist armed with a 9mm pistol), occurred 5 years before Gadell’s murder, and inspired NJSP to transition to autos (the HK P7M8).

The NYPD’s / Mayor’s / Commission’s reluctance to adopt lifesaving tools like hollowpoint ammunition, speedloaders, and auto pistols sure put a lot of citizens and MOS at risk.

Thank you for your service! We appreciate and respect it, here, and pray for all our current and former officers, deputies, patrolmen, troopers, marshals, etc.

I own a 1970s Ruger Police Service Six chambered in .38 Special (maybe for a security guard contract?). Since the majority of those were chambered in .357 Magnum, it can happily digest as much .38 Special +P as I can afford to feed it. Yes, those Rugers were built like tanks.

I have an older S&W 38 spl, I can find no model number. I use R&P 38 spl wadcutters they do the job for me.

Do you have info on Winchester Supper-X. Subsonic Deep Penetrator.

38 Special+P

147 GR. Jacketed Hollow Point

XSUB38S

I have several boxes.

I have no specific information on that load, Dave, and no experience with it, but I can speculate. Without seeing it, my guess is that it uses a conventional cup and core JHP (probably the same 9mm, 0.355” bullet used in their 9mm OSM load), otherwise they would have branded it as a Silvertip or Talon/SXT/Ranger load, using one of those more advanced bullets. I suspect that load dates to late 80s/early 90s, and was an attempt to provide revolver shooters a load that performed similarly to Winchester’s 9mm OSM load. Although I’ve not shot it, my guess is that it’s not an exceptional performer. It’s likely a relatively low energy load (maybe 800-850 fps in a 4” gun?) that wouldn’t open up that JHP very reliably (hence the “Deep Penetrator” label). Federal had to push their more sophisticated Hydra-Shok bullet to +P+ pressures to get velocities and performance close to the 9mm ammo they were trying to replicate for the Fan Belt Inspectors, so I’d suspect your +P Winchester load is a little slower, packs less energy, and doesn’t open up as much. I’d expect the bullet to show little upset and act a lot like ball in gelatin (maybe 15” to 16” penetration). Unless you have a way to chrono and gel test it, to see what it really does, I think I’d burn it up as range ammo, and rely on a better load for defense. I’d personally be more comfortable loading with 148 WC, 158+P LSWCHP, 130+P SXT, or 135+P Gold Dot, in lieu of that load. Again, all of that is speculation, based on my experience, so take it for what that’s worth.

Idaho State Police used the Winchester (LE Only) 110 grain SJHP +P+ load when ISP switched to the Model 65 in 1979. Dad was a firearms instructor and had stashed away several boxes of the Winchester load which stayed with him when ISP changed over to the Model 4586 in 91. Those boxes came to me (along with a few that acquired on my own) when he passed in 2016. Even though the cartridges are now over thirty years old they still pack a wallop. I haven’t fired them through a chronograph, but they do a number on water jugs, melons and other “scientific” mediums. I fire the loads in my 357 Magnum revolvers. Don’t want to beat up my 38 revolvers.

Jeff, it’s great to hear from you again. Thanks for documenting the use of that load with Idaho State Police! I think your policy of shooting those in your .357s is wise.

You would have a hard time convincing me there is any difference in the dash model 64 or 65 other than how the cylinder is reamed. It makes no sense for a manufacturer to have extra slightly inferior parts sitting around for the .38

Good article but I’m a bit disappointed that it didn’t go into further detail regarding 38-44 158 gr loads. By the way, the 38-44 was never loaded with “FMJ” as the article stated. There were two types of bullets made for the 38-44, one was the standard 158 gr round nose lead and the other a metal capped 158 gr lead bullet (bearing surface was lead). The 38-44 in its 1125 fps versions were discontinued shortly after WW2 and replaced by the forerunner of the +P round, or Remington “Hi-Speed” and Winchester/Western “Super X” (when Super X meant high velocity)…I’ve seen published chronograph data for these showing 940 fps in 4 inch tubes and 1025 fps in 6 inch…only Remington’s 38 Spl +P 158 gr LHP load of today comes close albeit a bit slower.

Thanks for the education Eric! I appreciate you sharing the valuable history with us. The article was already so long, there wasn’t space for a deep dive into the .38-44, but I wanted to ensure it got a mention, at least. The cartridge actually deserves an article of its own. Maybe that would be a great project for the future.