Continued from The Great Revolver Frame War–Part I

Meet My Big Brother

The introduction of stainless models gave Smith & Wesson a huge boost (and created some big headaches–a story for another time) but they knew they couldn’t ignore the lingering problem in their flagship police revolver. In the wake of the California Highway Patrol’s tragic Newhall Shooting, there was an increasing emphasis in law enforcement circles to abandon the long established practice of training with low powered target ammunition (like wadcutters), but carrying full power ammunition (including Magnum ammunition) on duty. Agencies from coast-to-coast began to mandate full power duty ammunition during all training and qualification events. This trend coincided with an increasing shift towards .357 Magnum ammunition, which was adopted by many officers and agencies in the violent and turbulent 1970s as a way to improve the effectiveness of police handguns.

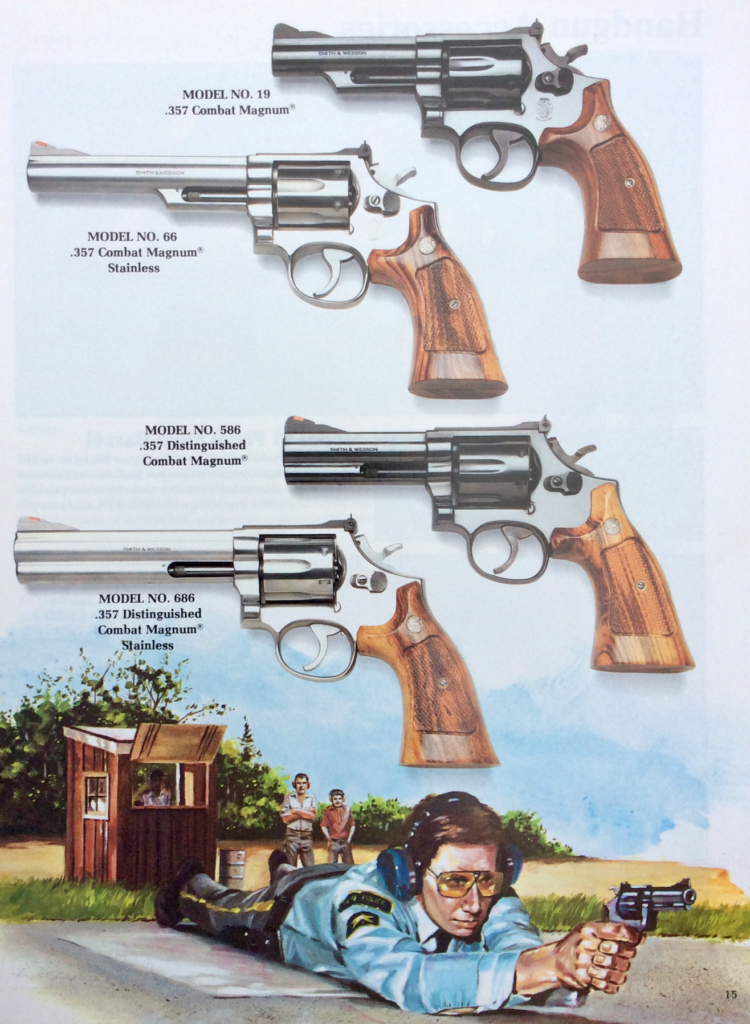

This was bad news for the Combat Magnum, so Smith & Wesson went back to the drawing board and created the first new frame size since the J-frame had been introduced in 1950. The new frame was designated as a Medium-Large frame, falling between the Medium K-frame and the Large N-frame. Smith & Wesson called it the L-frame. In terms of grip size and trigger reach, the L-frame mimicked the dimensions of the ever-popular K-frame, but the top half of the frame was taller and more robust. The most important feature of the new L-frame was that the taller cylinder window eliminated the need to relieve the forcing cone, fixing the principal weakness of the Combat Magnum.

Smith & Wesson unveiled the new gun in 1980, in both blue and stainless steel. The Distinguished Combat Magnum (Model 586) and Distinguished Combat Magnum Stainless (Model 686), with their full length underlug barrels, instantly represented the new zenith for police revolvers, and they were met with great acclaim. Suddenly, the strong and beefy Security Six didn’t look as strong or beefy–it just looked like the kid who got sand kicked in his face at the beach.

Two Can Play That Game

Sensing the turning tide, Ruger went to work designing their own Medium-Large frame, resulting in the GP100 in 1985. The GP100 upped the ante on beefiness. Barrel threads got thicker, the topstrap got thicker, the cylinder got thicker . . . everything got thicker. With its larger frame and full length underlug barrel, the GP100 looked like a brute.

But it incorporated some notable advances, as well. The modular disassembly scheme of the Security Six remained, but the Six grip frame was radically redesigned. Instead of a full profile grip, with a frontstrap and backstrap sandwiched between grip panels, the GP100 incorporated a peg-style frame that was completely covered by wraparound grips which placed a layer of recoil-absorbing rubber in front and back. This reduced felt recoil and made the heavy-framed GP100 a champ at handling powerful Magnum loads.

Additionally, harkening back to the acclaimed Smith & Wesson Triple Lock design, the crane incorporated a latch to lock it into the frame. This locking system eliminated the more distant and less positive lockup on the tip of the ejector rod, and improved the strength and rigidity of the lockup on the new gun.

If Smith & Wesson had bested Ruger’s claim to leading strength in class with the Distinguished Combat Magnum, the GP100 was determined to make a comeback and knock the crown off its head. In Bill Ruger’s words, “our direction is towards perfection,” and they certainly thought they had achieved it.

Showdown

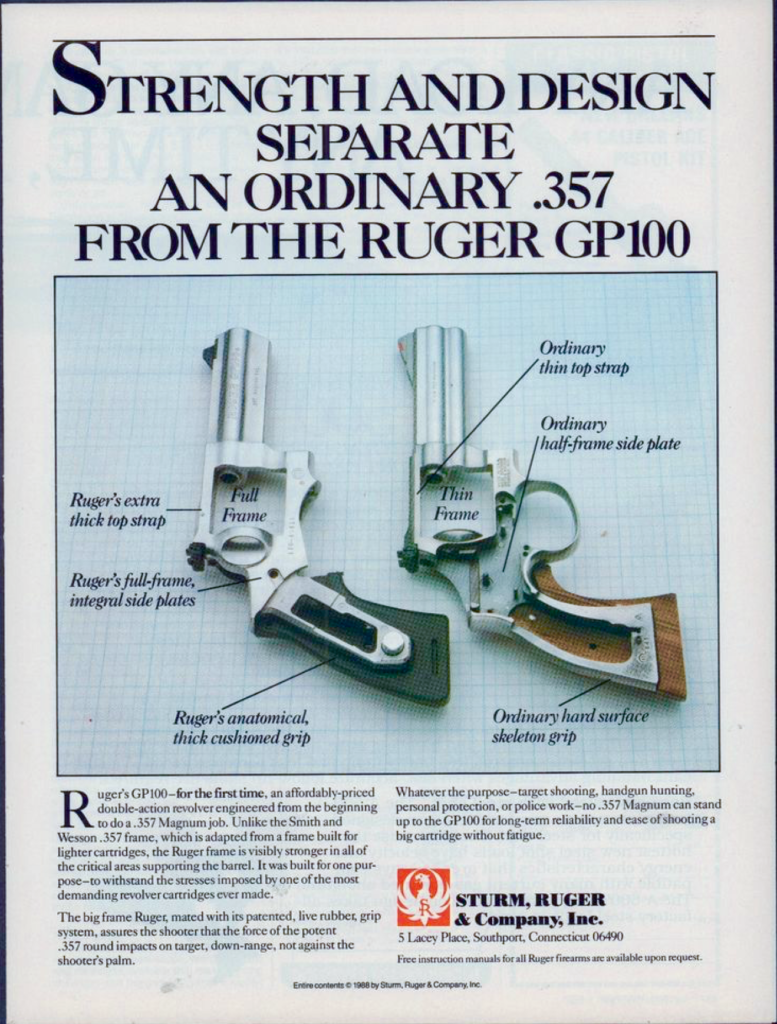

The stage was now set for one of the most entertaining marketing battles to grace the pages of the gun magazines, pitting the two guns against each other in an attempt to win the law enforcement and commercial markets. The first to come out swinging was Ruger, with an ad that unabashedly compared the two stripped frames, side-by-side. Echoing a familiar message from years past, the Ruger ad emphasized the strength of their design compared to the Smith & Wesson, but unlike previous efforts, there were no indirect, coy references to nameless competitors.

The boys from Southport were calling out the boys from Springfield by name! Ruger’s ad threw down the gauntlet, claiming the GP100 to be the first example of a gun “engineered from the beginning to do a .357 Magnum job.” It explained that:

Unlike the Smith & Wesson .357 frame, which is adapted from a frame built for lighter cartridges, the Ruger frame is visibly stronger in all of the critical areas surrounding the barrel. It was built for one purpose–to withstand the stresses imposed by one of the most demanding revolver cartridges ever made.

Arrows pointed out the “ordinary thin top strap,” “thin frame,” and “ordinary half-frame side plate” of the Smith & Wesson, and showed how the corresponding Ruger dimensions were larger and how the frame was one solid piece. The ad summarized that “no .357 Magnum can stand up to the GP100,” in the most definitive air possible. Wow.

By today’s measure, the words may not seem as powerful and damning as they were at the time, but for the company that introduced the .357 to the world in 1935, this was the equivalent of a Magnum-level kick in the ball bearings. The entire gun world waited with baited breath for the response from Massachusetts. Surely, Smith & Wesson could no longer ignore the barking dog at their feet? Surely they could not allow Ruger’s direct attack to go unanswered?

No, they couldn’t. But magazine lead times being what they were, we’d have to wait for many long months by the mailbox before the response came. It was worth waiting for.

Heavy Metal

Before we get to that, however, it’s important to understand the differences in the construction of the two products. The process used to build the GP100 frame is known as investment casting. Bill Ruger pioneered the use of investment casting in firearms manufacturing, and perfected the art to the extent that other industries have long viewed Ruger (and their associated Pinetree Castings operation) as a leader in the technology.

In investment casting, a highly accurate and detailed wax pattern of the final product is coated with ceramic, which hardens as it cools. After the ceramic has hardened, the wax is melted out of the ceramic, leaving a precision ceramic mold for molten metal to be poured into. When the metal solidifies, the ceramic mold is broken off, leaving a highly accurate part that requires very little machining or finishing.

The process is efficient and reduces costly machining operations, which allows a dimensionally accurate part to be produced for less. This was a critical component of Ruger’s business model from the start, which aimed to produce quality firearms at a price point that was lower than the competition. It was the key component that allowed Ruger to produce guns like the Security Six and GP100, which performed like guns that cost more.

There are tradeoffs with investment casting, however. When a metal is heated past its melting point, then allowed to cool, the grain structure of the metal is changed. Individual grains can expand, and the resulting solid can have a coarser and more irregular grain structure, with more surface porosity.

This does not happen when a metal is forged. A forged metal retains its finer grain structure, and is not as porous as a casting. A forged metal therefore tends to have greater tensile strength, increased ductility, and enhanced fatigue resistance than a casting of the same metal. If you have a requirement for a certain level of strength and fatigue resistance, you can meet it with either a forged or a cast metal, but you’ll need a greater mass of the cast product to achieve it. This is because the forged material is generally “stronger,” by volume, than the cast material is.

The Distinguished Combat Magnum, like all Smith & Wesson revolvers, has a forged frame. It can withstand the operating pressures of the .357 Magnum with less material than the GP100, due to the qualities of forged steel. When Ruger launched their ad campaign, Smith & Wesson knew that their gun didn’t have to be as thick as the GP100 to deliver the required performance. They knew that any attempt to portray it as weaker, because it was thinner, was misleading. Now they just had to figure out how to explain it to the public, in a way that they would understand. They did, and the result was unforgettable.

Smackdown!

The ad was the brainchild of a feisty marketing genius at Smith & Wesson, named Sherry Collins. Those who knew Sherry recognized that she was a force to be reckoned with, and when Ruger threw down the gauntlet, the fiery redhead (“not just fiery, but the whole forest fire,” said her friend, Tommy Campbell) was the ideal person to accept and counter the challenge.

The central focus of the ad was an open-faced hamburger, shaped in the form of a GP100, with the distinctive GP100 wraparound rubber/wood insert grips added to guarantee the provenance of said beef. The Ruger Burger* was ridiculously thick, standing a good two inches tall as it sat on the bun, and a pair of pickle slices and a splash of ketchup were perched on top in a manner that left you with the unmistakable impression of a bug-eyed face mockingly sticking its tongue out at you. A cluster of sour-looking grapes (brilliant!) sat next to the plate, along with a tall chocolate milkshake.

The headline tied the visual genius together. It said, simply, “There’s no question that thicker is better when it comes to burgers and shakes. But what does it have to do with revolvers?” For those who were unsure, Smith & Wesson readily provided the answer: “Not much.”

The text of the ad educated the reader about the differences between forged and cast frames, and smashed the idea that frame thickness could be used as a measure of strength. It advised that “thicker doesn’t mean better. Or stronger. It just means bulkier.” Smith & Wesson extolled the virtues of their forged frames and flatly declared that “we don’t have to add extra bulk to make our guns strong and resilient.”

The ad was a stunning counterpunch to the aggressive Ruger marketing, combining the right mix of satire and product promotion, and it brought hoots of laughter from readers all over. Serious gun cranks eagerly awaited the counter-counterstrike from Ruger, hoping for an entertaining escalation of the marketing brawl, but it was not to be. Ruger continued to enthusiastically promote its new design, but it did so with more discretion and less confrontation. The burger ad had dampened any enthusiasm for poking the competition in the eye.**

POSTSCRIPT

It’s interesting and ironic that the “Great Frame War” took place on the eve of American law enforcement switching en masse to autoloading pistols. By the time the burger ad ran, the double action police revolver market was starting to disappear with the looming onset of the Wondernine Wars. While the GP100 and Distinguished Combat Magnum were enthusiastically received by some officers and agencies, they didn’t serve in uniform for very long before they were replaced by self-stuffers, with generally horrible double action triggers that made many coppers yearn for their old revolvers.

Both the Ruger GP100 and the Distinguished Combat Magnum went on to great commercial success, however. Decades later, each of these guns remains the flagship product in its class for their company, and both have proven to be incredibly durable, ergonomic, and reliable designs. In retrospect, the “Great Frame War” was much ado about nothing, because both the Smith & Wesson and Ruger products proved that they were more than capable of taming the .357 Magnum.

The early fight for market dominance has subsided, and the positions of the two products are mostly settled by now. Both of the guns remain incredibly popular amongst revolver enthusiasts, and a Revolver Guy couldn’t go wrong with choosing either of these wonderful firearms. Either will serve you . . . through thick and thin.

*****

The author would like to thank Mr. Bert DuVernay for his invaluable assistance.

*(Note): In the days before Photoshop, if you wanted a picture of something, you actually had to find a real one to shoot. So, Sherry and her team had to grill a Ruger Burger for the photographers! Sherry’s friend and coworker, IPSC champion and U.S. Team Captain Tommy Campbell, said that grilling a suitable exemplar of the super thick burger “took a little bit of practice,” and they got to eat a few mistakes before they got one that looked good enough for the ad!

**(Note): The President of Smith & Wesson was reportedly not as enthusiastic about the ad campaign, and disapprovingly told Sherry he thought the ad was “smug.” In typical Sherry fashion, she made up a bunch of buttons and passed them out for S&W employees to wear. The buttons read, simply, “SMUG, AND PROUD OF IT!”

Sources:

Grennell, Dean A. Law Enforcement Handgun Digest, DBI Books, 1976;

Jinks, Roy G. History of Smith & Wesson, Beinfeld Publishing, 1977;

Jordan, Bill. “S&W Model 19: The Peace Officer’s Dream Gun,” American Handgunner Magazine, Vol. 2 No. 4-6, July/August 1977, https://americanhandgunner.com/classic-handgunner-editions/;

Supica, Jim & Nahas, Richard. Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson, Gun Digest Books, 2006;

Triggs, James. “Origins and Evolution of the Ruger Security Six,” American Handgunner Magazine, Vol. 1 No. 2-6, November/December 1976, https://americanhandgunner.com/classic-handgunner-editions/.

One element of this “frame war” is omitted, I believe.

And that item is the Colt Python.

Smith & Wesson essentially aped the .41 frame size

of the Python which had its roots in the Official Police

.38. Back when the .38/44 round was created, Colt

claimed it didn’t need a frame size like Smith’s

N-frame.

Indeed, when Smith produced the Distinguished

Combat Magnum, its contours mimicked those of the

Python. A sales point was that the Smith could use

basically the same leather and speed loaders of the

Python.

I remember one gunzine story in which the writer said

he saw prototypes of the Smith Distinguished Magnum

in the 1970s but Smith chose to be a “gentleman” and

not produce a “copy” of the popular Python at that time.

In a sense, I believe Ruger was not only playing catchup

with Smith but finally producing something as a direct

face-off with the Colt Troopers and Pythons.

It’s an excellent point, Ed, and there’s no doubt that the L-Frame and the Distinguished Combat Magnum were heavily influenced by the E-Frame and the Python, both dimensionally and cosmetically.

But that’s a whole other story. This story is just about the public battle between S&W and Ruger in the 1980s. Colt wasn’t a participant in that fight–they were completely ignored by those two in the marketing by the 1980s, so they weren’t discussed here either.

By the time the GP100 arrived, Colt was already into the crippling UAW strike that lasted for the next 5 years. Colt was the boxer on the ropes getting his last standing eight count, and neither S&W nor Ruger was paying them any attention, because they knew he was going down. Smith & Wesson and Ruger spent their marketing dollars against the real threat, and Colt was just left to take its natural course, which it did.

We’re working on some Colt stories and will definitely get around to the influential E-Frame as part of that, so please stay tuned! Thanks for your additions to the story!

Mike, that series on Colt would be most welcome. I’ve had a good bit of trigger-time with a friend’s Python, a real jewel of a collectible he got at auction. Best-shooting .357 I’ve ever fired, with a trigger that stunned me with its smoothness, though recently the gun’s latch spring or bushing broke when firing standard .357 rounds. Colt no longer services them, but they do maintain contact with gunsmiths trained to work on their revolvers.

I’m curious–who did Colt recommend to your friend for the work?

All the Old Guard of Python ‘smiths are gone now–Jungkind, Moran, Sadowski–and Grant Cunningham hung up his shop apron. If I was going to have some work done on a Colt, I’d probably start with Bill Laughridge and crew at Cylinder & Slide, or Alan Tanaka at AT Custom Guns. Any decent ‘smith should be able to repair the broken thumbpiece on your friend’s gun, but for action work or something serious, I’d probably start with those guys.

Yes, I’ll definitely be doing some work on a Colt article. Stay tuned!

Nicely done, and very educational. I like both. Guess I need one of each?

I like the way you think!

Fantastic! Thank you for an excellent article! Love both, always fun to learn more about them. And the burger ad… I guess it answers that old question: “Where’s the beef?”

One of the amusing (to me) things that came out of this frame war is the lingering belief that Rugers are thicker in all areas than Smiths. One doesn’t need to look very far to find a forum post where someone says an L-Frame has a narrower cylinder than a GP100, so it will be slightly more comfortable to carry. With a little research, one discovers that an L-Frame cylinder is 1.565″ in diameter while a GP100 cylinder is 1.540″. While 25/1000″ isn’t much, the Ruger cylinder is actually narrower. In that regard, I think Ruger did their marketing a little too well.

Good stuff Mike! Although the Smiths are sexy…a 4” GP100 is it’s cute tomboy cousin.

Outstanding article! I remember those ads well, I was a teenager at the time. I wasn’t paying attention until S&W released that burger & shake ad.

I personally lean towards the GP100 just a little bit more than the 686. After firing a GP100 enough times, the difference in trigger pull is negligible to me. However, the GP100 is easier to break it down into its essential parts for deep cleaning. You can do that with the 686, but you’d better have a set of jewelers screwdrivers and a steady hand. I also like the fact that after firing a lot of magnum ammo in my GP100, the only screw I have to check for tightening is the tiny little screw that holds in the cylinder release.

I think it’s also interesting that Ruger just now released the GP100 with 7 shots, presumably to compete with the 686 Plus models (although, they’re about 20 years late on that one).

Excellent article! As one who continues to carry a S&W Model 66 with a 2.5″ bbl for protection despite the overwhelming popularity of the semi-auto (and yes, i own a 9mm pistol), the information you provide is not only extremely welcome but also very useful, practical, and timely. Thank you for providing good, solid information about wheelguns and wheelgun ammo that many of us still use to keep us safe. Keep up the great work!

Very informative article. I was in high school when the frame war was going on and I wasn’t paying attention. By 1985 my focus was on autos thanks t0o “Miami Vice” , Jeff Cooper and the selection trials for the U.S. military’s 9mm pistol. Years later I’ve evolved into a revolver aficionado and I love all the history.

One last thing. Look at the top strap on the 3″ GP100 with fixed sights. It isn’t as thick as the GP100 with the adjustable sights. The frame on the 3″ version is also more…….sculpted than the other versions. Just a passing observation signifying nothing, but it’s fun to point out.

Great collection of historical information about two of the giants in the industry we all love. Full disclosure: I’m a S&W guy when it comes to revolvers. I have also carried their pistols and I like them too. I have always admired Colts revolvers , but have found their cylinder timing tends to be off, degrading their double action capability. I have always owned and admired Ruger single action revolvers, but have never fired one of their double action revolvers. As pointed out in this excellent article the S&W Model 19 was king when it came to a duty gun.

Thank you Sir! The Model 19 occupies a special place in this handgunner’s heart.

I bought one of the early Ruger Security Six revolvers. My biggest reason was you could not find either a Colt or Smith for sale. The barrel was not clocked correctly and the front side was off by a few degrees. I just adjusted the sights. I was just learning to handload and shot many thousands of very hot rounds through this gun and carried it a million miles. Only other problem was the threads on the ejector rod would work loose once in a while. Anyway availability was also a big consideration.

Thanks Ron, appreciate your report from the era. The ejector rod unscrewing and clocking issues weren’t unique to the Security Six, for sure! I’m sure that tough gun held up well to your hot handloads. I hope you still have it.