I was having a “campfire conversation” with RevolverGuy Dean Caputo, recently, about the handling characteristics of various handguns. At one point, we were busy comparing the pointing characteristics of some popular snub revolvers, and we discovered that we shared a mutual appreciation for the “pointability” of the J-Frame revolver.

Special J

All of the J-Frames seem to point pretty well, but we were both particularly impressed with my favorite J-Frame, the Centennial. Dean also expressed his appreciation for the more homely, but eminently useful, Bodyguard frame, with which he has much more experience, than I do.

There’s a host of other small frame revolvers out there from various makes, but we thought the J-Frames just seem to naturally point better than most of them. “Why is that,” we wondered? What is it about the J-Frames, that make them handle better than the others? For that matter, why do the J-Frames seem to point better than their larger-framed, service gun counterparts, the K and L-series revolvers?

Low rider

In the finest RevolverGuy fashion, we conducted a comprehensive and scientific analysis of the problem . . . um . . . well, actually, we just jawed about it for a while, but it was really good stuff, and you shoulda been there. ; ^ )

Cutting to the chase, we decided that one of the keys to the J-Frame’s natural indexing is its lower bore axis.

For those unfamiliar, “bore axis” is an expression that refers to the distance between the centerline of the bore and the highest place on the frame where your hand is supporting the pistol (usually the web of your primary hand). With a low bore axis, the centerline of the bore is located close to the web of your hand.

We often think of bore axis in terms of recoil control, because a lower bore axis helps to reduce muzzle rise, by virtue of a shorter moment arm. However, bore axis also has a lot to do with the way that a gun indexes, because it’s easier to point a gun whose boreline (and thus, sighting plane) rides close to the same plane as your extended index finger (the one you point with).

Working with the J

I had an observation that I shared with Dean about this, which might be illustrative. Although I’ve been shooting revolvers forever, and enjoy working with all of them, over the past several decades, my revolver shooting has become increasingly snub-focused. My favorite revolver remains the medium frame Combat Magnum, but the honest truth is that I shoot it very little these days, and spend the majority of my time with the smaller, Model 640 Centennial that I carry.

As a result of the increased time I spend with the small frame Centennial, when I pick up a medium size K-Frame or medium-large size L-Frame, it takes a little bit for me to “get in the groove” with them. When I raise these guns on target, I often find that my eyes are looking for the sights in a much lower plane than they’re actually located. I wind up having to remind myself that the sights are now “up there,” and make adjustments to locate them (very much like a beginning red dot shooter can’t “find the dot” on his initial presentation, and has to move his head around to find it). It doesn’t help that the sight plane on these larger revolvers also rests higher than the autoloaders that I’m accustomed to working with, which tend to have lower bore axes, much closer to the J-Frame.

Such is the power of habit, but I also think there’s a natural advantage to a gun that has a lower bore axis, as it really seems to improve your ability to point the gun kinesthetically, without reference to the sights, and have it properly aligned on the target.

How they measure up

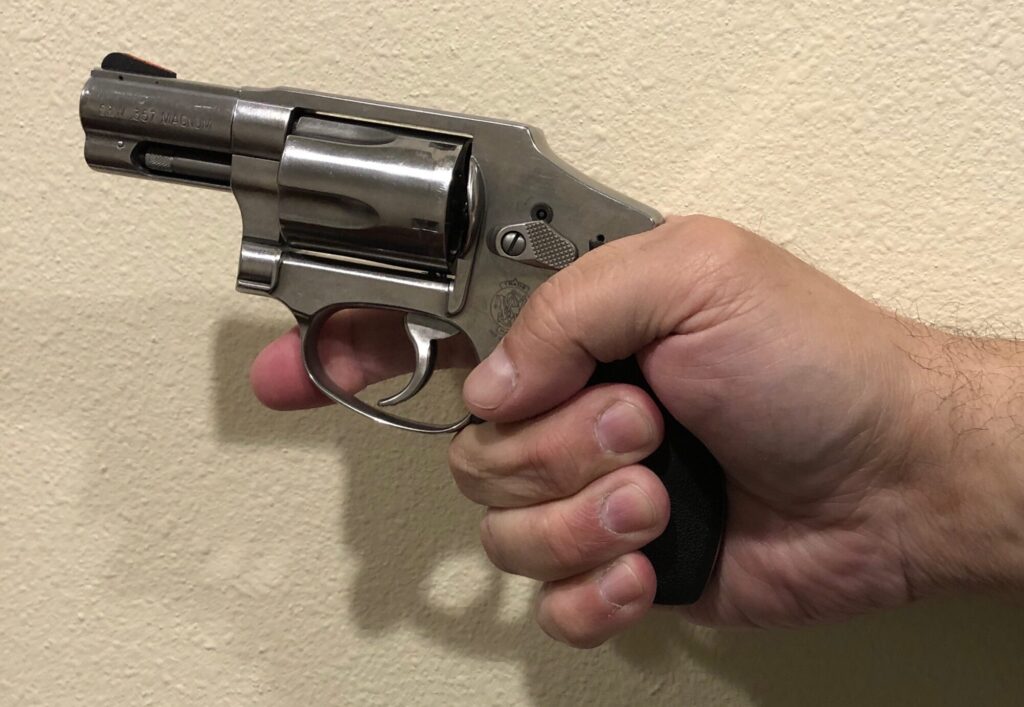

If we look at a gun like the basic, exposed hammer J-Frame, we see that a proper, high grip leaves the web of the hand just underneath the ejector rod, which makes the gun “ride low” in the hand:

The same relationship applies with the larger K and L-Frame guns, but because these guns have a taller cylinder window in the frame, the distance between the bore and the web of the hand is much larger than it is on the tiny J-Frame:

But all J-Frames aren’t created equal, though. As I mentioned, both Dean and I feel that the Centennial frames tend to point better than the exposed hammer versions, and I think the lower bore axis has something to do with that. You can see how the shape of the Centennial’s frame naturally allows the hand to ride higher on the backstrap, thus shrinking the distance between the hand and the centerline of the bore. In fact, with a high hold, the web of the hand tends to rest just under the bottom edge of the muzzle on the Centennial frame:

An even more aggressive, “choked up,” grip can even leave the web of your hand overlapping the recoil shoulder, putting the web of your hand in nearly the same plane as the bore, without much difficulty.

Bodyguard thoughts

The humped Bodyguard frame allows the shooter to grip it higher as well. Although you could comfortably grasp the gun with the web riding in the recurve below the shoulder of the frame (would that make it the “armpit?”), it’s comfortable to choke up on the frame a bit, and grasp it much higher, about midway between the placement on the exposed hammer models and the Centennial, with the web riding along the axis of the ejector rod:

Dean has a lot of experience with the Bodyguard (having carried one on and off duty for many years, before the Centennial frame was resurrected in 1989), and feels he can actually grip that style frame even higher than the Centennial frame, which would make the gun point very naturally for him, indeed.

Dean notes that Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department armorer Jerry Maxwell dehorned the hammer on his Model 49 in 1980, and advocated (in concert with the LASD academy instructors) a very high hold on the backstrap of the Bodyguard—so high, that you could feel the back of the hammer touch the web of your hand when the trigger was stroked in double action. The dehorning job helped to facilitate this hold, by preventing the spur from getting hung up on the web of the hand, and Dean says that with this hold, the web of the hand actually lays over the top of the hammer spur when it’s cocked in single action mode. He reports no interference in either operation.

Centennial versus Bodyguard

My own experience with the Bodyguard is limited. I’ve handled many of them, but have only fired one a few times. The majority of my J-Frame time is with the Centennial design, which I greatly favor, but it’s my impression that the Bodyguard has a more “vertical” grip profile, that is less angled than the Centennial. In autopistol terms, in my hand, the Bodyguard feels like it points more like a 1911, while the Centennial points more like a Glock.

However, a comparison of the two guns indicates this difference may be more imaginary than real:

Apparently though, I’m not alone in my impression. Dean remembers an article to this effect, written after the reintroduction of the Centennial in 1989. As Dean recalls, the author (who may possibly have been Mas Ayoob? See his thoughts on the Centennial vs. Bodyguard starting around the 1:00 mark in this video) felt that when the two guns were fired from the hip, the Bodyguard tended to point slightly low, but still quite close to level, while the Centennial tended to point much higher, requiring a conscious correction to lower the bore. As these photos indicate, that seems to be Dean’s experience, too:

If the Centennial naturally points a little higher, that might explain why I’m so comfortable switching back and forth between it and the Glock (which also points high, by virtue of its angled grip frame).

Other comparisons

We saw earlier how the larger K and L-Frame guns tend to sit with the web of the hand aligned with the bottom of the ejector rod shroud. It probably won’t surprise you then, that the similar Ruger 1700-series (GP100) frame and Colt I (Python) frame share similar high bore axes:

What may surprise you though, is this same relationship seems to extend to the Ruger 5700-series (SP101) frame, even though it’s a compact revolver (well, as compact as the “Old Ruger” could make it, with their tendency to overbuild everything!):

The new Colt Cobra frame tends to follow the same pattern as well:

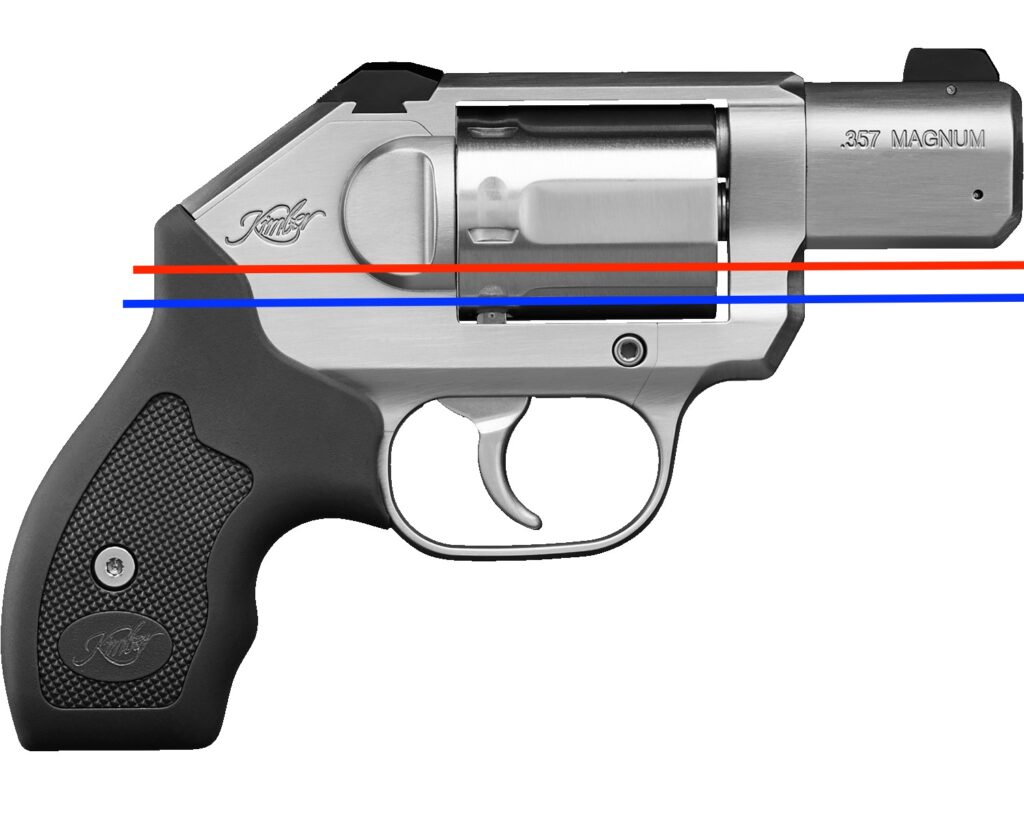

As does the Kimber K6s:

The Kimber is an interesting study, because even though it has a recoil shoulder that looks similar to the Centennial’s, there are subtle differences in the angles that make it feel very different in the hand. One of the features I like most about the Centennial frame, is that it allows me to “choke up” on the grip and place the web of my hand up very high on the backstrap of the revolver. Doing so has the effect of lowering the bore axis, and it’s quite easy for me to grip the Centennial high enough (with the web of my hand riding on or over the recoil shoulder–the “hump” of the gun’s grip frame) that the gun sends its recoil straight back into my hand, and the muzzle hardly rises at all, in recoil.

When I shoot the Kimber K6s, though, the shape of the grip frame tends to force my hand lower on the backstrap. It’s not as comfortable to choke up on the recoil shoulder, and I wind up gripping it below the hump, around the red line in the photo above (note the significant difference in bore axis, compared to the Centennial—the web of the hand rides significantly below the ejector shroud on the Kimber, as compared to the bottom edge of the muzzle on the Centennial).

This is still higher than the spot where I see most people grip the K6s, marked by the blue line in the above photo. In example, look how high the K6s rides in Steve Tracy’s hand at the 2018 SHOT Show:

The Ruger LCR, by comparison, rides low in the hand like an extended hammer J-Frame:

This probably helps to explain why I found the LCR to point so well when I was putting it through its paces for RevolverGuy (shown here is the 9mm version, which I liked very much):

Get a grip

Of course, while the frame of the gun establishes the basic pattern, angles and dimensions we have to work with, the shape and size of the grips has a big impact on how a gun points as well. A set of grips that covers the backstrap, for example can change the angle at which the gun points while it rests in your grasp, as can other features like finger grooves or fillers behind the trigger guard (as you see on most factory grips these days).

Note, for example, how this Colt Police Positive rides with the factory grips that follow the lines of the grip frame:

And compare how the same gun rides with a Tyler grip adapter, which fills in the area behind the trigger guard:

This ability to adapt the fit of the gun to your hand, by trading stocks, is one of the significant benefits that revolvers have traditionally enjoyed over most autopistols. These days, we’re seeing a lot of autopistol manufacturers try to incorporate some degree of grip customization with replaceable inserts (as on the Walther PPQ or Smith & Wesson M&P), but there are practical limits to how much you can alter an auto’s grip, with a magazine located underneath.

The point

With enough repetition and training, you can get used to any gun, of course. A dedicated training program will help you to build the habits that will make any gun point like an extension of your hand, but it’s kinda nice when the gun wants to do that naturally, from the start.

We’ve all got different hands and preferences, so your results will differ from mine and Dean’s, but I think all of us will agree that some guns just naturally point better for us than others. When you’re considering your choice of firearms, that might be a really important factor to consider, don’t you think?

The Colt Police Positive photo seems to show the index finger has to reach down for the trigger in front of the middle finger. That doesn’t look comfortable to me.

I have a 1911 production example in .38 “New Police” (S&W, for the rest of us!), and as awkward as it looks, if you have smaller hands (like a medium sized glove, where a Glock Gen 3/ Medium backstrap Gen 5 doesn’t quite fit), its surprisingly comfortable! And it points like an extension of my arm, on the rare occasion she comes out to play. You should try just service panel grips sometime, you might like it!

Great article. I notice this difference when going from my usual SP101 to my Armscor M200. Since the SP101 has a larger cylinder than a J-Frame, and the Armscor has a smaller cylinder than a K-Frame (about .001″ larger than a D-Frame), the difference is less than between the S&W guns, but I still find it extremely noticeable. It is also why I opted to go with a SP101 for a 4″ gun. I don’t need a 6th shot (until it comes time to justify another gun to my wife), and switching between a fixed sight and adjustable sight SP101 is less jarring to me than the alternatives.

I wonder if the Chiappa Rhino benefits from that low bore in the same way? Anyone?

I haven’t shot one, but it feels awkward in my hands. I don’t know how natural of a pointer it would be.

I think familiarity has something to do with it…..I grew up on S&W model 10s and 66s..and still shoot them regularly. ..they point great for me…I had to work at pointing the the J frames…

Most definitely!

Great article! I have noticed the same thing with my S&W revolvers. My natural point of aim is spot on with the j frames. My sight alignment is right on when I bring the gun up in the firing position. But, my k/l/n frame S&W’s don’t, or at least not at first when I am drawing cold out of th holster. Seems like the larger the frame, the lower the point of aim I experience or is that just me?

I have owned a S&W Model 10, 49, 60, 642, and a Ruger LCRX. I now own two 642s for this very reason. See Wilson Combat’s Gun Guys Episode 35 with Ken Hackathorn and Massad Ayoob on YouTube. Ayoob compares the Centennial vs Bodyguard shootability due to bore axis and grip angle.

Thanks COLTK! I’ll link to it in the article. Appreciate you pointing out that episode!

Thank you Mike, for an informative article. You clearly articulate why the Centennials have less felt recoil than a standard frame. My subconscious knew that, but now I know why!

Thanks Kevin! Glad you enjoyed it!

Natural point of aim was my biggest grip-gripes with target-stocks on my Model 27; my hand sat way too low and under the trigger. A set of Magnas enables my XXL hand to grip up high and the revolver points very naturally. A second choice is pre-war style Service stocks, but those are a bit too much fun for shooting Buffalo-Bore or my heavy 230gr magnum loads.

As always, one of the best and most informative gun sites around.

Mike,

You answered me an old question in this post.

In 2010, I was impressed how accurate was an old Rossi model 31 (an odd 4-inch J-Frame). An apparently odd combination of frame size and barrel length has a technical reason to exist.

I was looking at my k6s while reading this. Thinking to myself how the k6s allows a higher grip than my old 442. I was surprised to see you came to the opposite conclusion.