In Part One of this series, we talked about how the MIM process works, and in Part Two, we discussed the pros and cons of manufacturing products with MIM methods. In this next installment, we’re going to explore Smith & Wesson’s experience with transitioning to MIM production, and take a look at some of the engineering improvements that MIM allowed them to make to their famous line of revolvers.

Seeking Options

By the 1990s, Smith & Wesson’s manufacturing operations were due for a shakeup. The manufacturing technologies, techniques and processes which had served them well for so many years were starting to show their age, and some changes were necessary to guarantee efficiency, profitability, and consistent, quality production in the future.

To figure out the next steps, the company conducted a survey of available technologies and manufacturing processes, to see if there was any potential to improve pistol and revolver production at Smith & Wesson. The Springfield, Massachusetts company had a mature operation, that was already nearing its 150th anniversary, and they could have just kept doing what they were already doing, but it was good stewardship to see if there was any room for improvement.

Casting About

Their largest competitor in the revolver market was Ruger, who had been quite successful building a business around investment casting. Ruger not only built quality guns from parts that were largely made from castings, they had also migrated into supporting other industries with their Pine Tree Castings operation, which allowed them to apply their casting expertise to other endeavors.1 Through Pine Tree Castings, Ruger manufactured products for companies in the architectural hardware, power tools, sporting goods, medical, marine, and other industries, so there was good reason for Smith & Wesson to consider casting as a viable option.

There were complications which made casting a bad fit for Smith & Wesson, though. Every process has its own pluses and minuses, its own problems to deal with, and while Ruger had successfully navigated those waters, it wasn’t going to be easy for Smith & Wesson to do the same.

The Smith & Wesson revolver frames, for example, didn’t lend themselves to casting. You can get a very strong and durable frame from casting, as Ruger does, but it comes at the expense of the frame being a little thicker. The Smith & Wesson frames featured thinner walls, and used less material in certain high-stress areas, than equivalent Ruger frames, because they were designed around forging and machining processes. Those processes allowed Smith & Wesson to get the requisite strength in a thinner profile, and if Smith & Wesson was going to start casting their frames, instead of forging them, they would have to completely redesign the guns. The guns would have to be enlarged to accommodate the casting process, and that was simply a non-starter. Not only would it have been expensive to do so, it would have been unacceptable to their customer base to make the guns bigger and heavier.

Casting the smaller parts was technically feasible, but would have required an investment that would have netted very little, if any, return over Smith & Wesson’s current practices of machining the parts from forgings and raw stock, so it didn’t seem a financially viable undertaking.

Unsuitable Tech

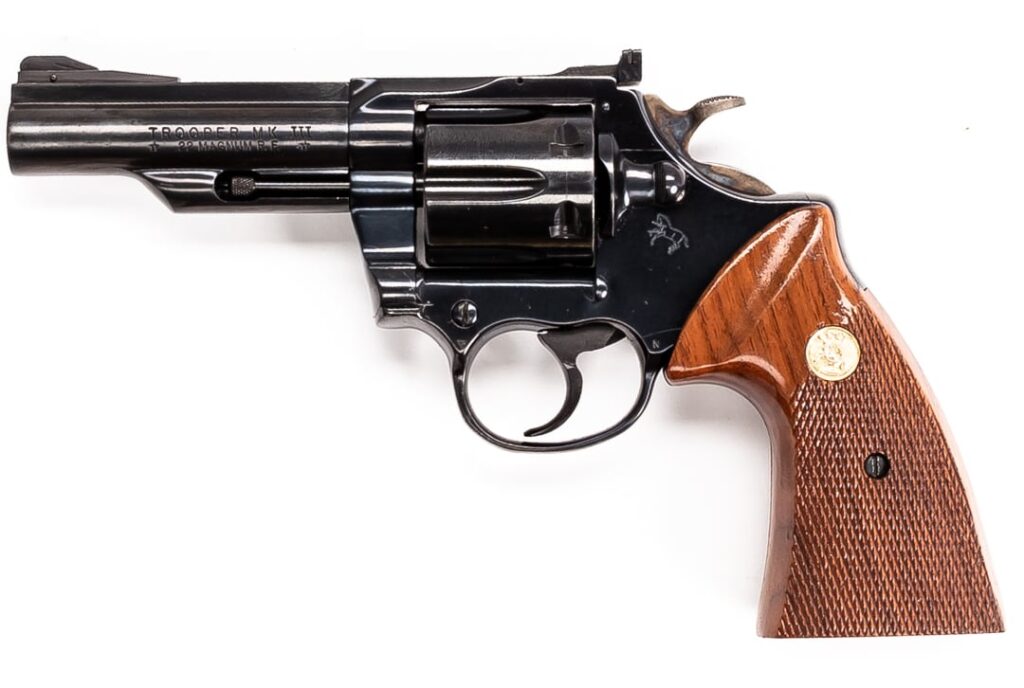

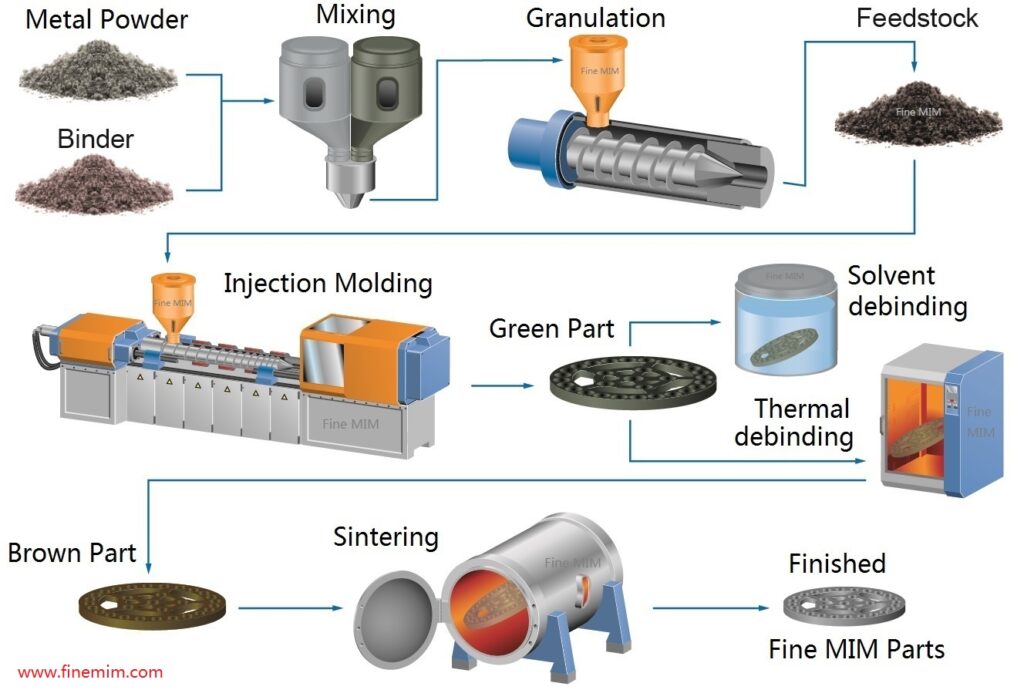

Other companies, like Colt and Remington, had previously flirted with compressed powdered metal technology, to make small parts for their guns. In this operation, extreme pressure is used to compress powdered metal, which is then heated to sinter and solidify the material.

Colt, for example, made good use of the process for many of the internal parts in the Mark III series of revolvers (the .38 caliber Metropolitan Mk III, the .357 caliber Lawman Mk III, and the .357 caliber Trooper Mk III), which had been completely redesigned by Dick Baker. Baker’s action was a radical departure from the standard Colt pattern, and improved on the traditional Colt V-Spring, but the compressed powdered metal parts weren’t always seen as an improvement.2

Gunsmiths who tried to file or polish these compressed metal parts were dismayed to discover the material didn’t act like other metals, and sometimes crumbled away, once you started working on them. Additionally, there were reports of fatigue and failure with the compressed powdered metal parts, with hammer spurs breaking off during firing, and the like.

These complaints are rooted in the fact that compressed powdered metal parts only achieve 75-93% density (as compared to 96-100% for MIM), and also suffer from high levels of porosity. The lower density and higher porosity, compared to a forged or MIM product, makes for a less robust metal that is unsuitable for use in certain, high-stress applications.

An additional problem with compressed powdered metals, is that the process only works well enough to make simple, “2-D” parts. You cannot make parts with complex, raised shapes, or with cavities, holes, and recesses. Remington, for example, was unable to press out parts with holes for pins and screws, which had to be drilled and tapped later on, after the part came out of the oven. The technology could be useful in certain applications, but it was ill-suited for the complex parts that Smith & Wesson needed to manufacture for their revolvers.

A MIM Solution

The new kid on the block, metal injection molding (MIM), offered a lot of promise though, and the Smith & Wesson Revolver Engineering team was immediately attracted to its possibilities.

As we’ve previously discussed, MIM offers great potential for companies looking to make small, complex parts that require little-to-no machining. While the MIM process requires a lot of work up front to set up, once the molds, formula and process have been established, you can economically produce a high volume of very consistent, high-quality parts if you have a disciplined manufacturing process.

To explore MIM solutions, the Revolver Engineering team made contact with several companies that were in the MIM business. One of these was Advanced Forming Technology (AFT), now called ARC Colorado Inc. (ARC), a part of ARC Group Worldwide.

The team made several visits to ARC, with S&W metallurgist Jim Grochmal, PhD, serving as the “eyes and ears” for the company. Jim carefully dissected and examined sample parts made by ARC, and determined they were of high quality and excellent consistency. The S&W Revolver Engineering team thought ARC had a good process in place already, and felt that they could make a better-quality gun with MIM parts produced by ARC, so they went back to Springfield and sold the idea to upper management.

Management agreed with the recommendation, and Smith & Wesson made the commitment to move to MIM for a lot of the small parts in their firearms. Because of their expertise in forging and machining, it made more sense to continue making frames, cylinders, barrels, and other major parts in house, but Smith & Wesson would contract with ARC for parts like rebound slides, hammers, triggers, sights, and cylinder stops which could be improved by making them with MIM. In the transfer to MIM, Smith & Wesson eventually switched 54 components in their pistol and revolver lines over to MIM production.

Partners

Smith & Wesson also partnered with Parmatech, in Petaluma, California, to produce some larger MIM parts for their guns. With ARC handling the small parts, and Parmatech making the bigger ones, a new era of manufacturing at Smith & Wesson was well on its way.3

From the very start, Smith & Wesson worked closely with the vendors, in a “share key” operation, to develop the unique formulas that would produce parts with the desired characteristics. While ARC and Parmatech were already experienced MIM houses, with good MIM feedstock recipes and tight processes that delivered consistent shrinkage, Smith & Wesson wanted to use their own special blends of metal powders, to get parts with the strength, ductility, and durability they wanted.

This added time to the schedule, but it was worth the extra effort. It took ARC about six to twelve months, for example, to learn about working with the new formula and work out all the production bugs, but they were able to perfect the manufacturing process with the new mix and deliver exactly what Smith & Wesson wanted.

The Revolver Engineering team was prepared to reject the ARC and Parmatech samples early on, and look elsewhere, if they weren’t better than the parts that Smith & Wesson had been manufacturing for themselves. Fortunately, they were very pleased with the quality and consistency of the ARC and Paramtech products, and were glad to enter into long-term relationships with the vendors.

As happy as they were to outsource a significant portion of the small parts production to ARC and Parmatech, Smith & Wesson still wasn’t willing to subcontract the manufacture of the major components that were machined from forgings or billets. Smith & Wesson had developed quite an expertise in building parts like frames and cylinders, and wanted to retain that production in-house. It had been hard, at first, for the company to make the transition to machining stainless steel in the 1970s, but by the 1990s they were experts at it, and there was nobody else they would have preferred to do the job.

MIM Improvements

So, we’ve talked about some of the components that are now made via MIM, but how do the new parts differ from the old ones?

RevolverGuy’s sources advise that the MIM parts have maintained better tolerances than the old ones and are much stronger than the old ones, too. While they may not be as attractive to some customers, they’re a lot tougher, are improved in their design, and will offer better service life.

Take the new MIM hammers, for example. Retired Smith & Wesson Manufacturing Engineer Norm Spencer (of L-Frame fame) explains there’s a misconception that the old hammers were forged steel parts, but they weren’t . . . at least not for a long time. Smith & Wesson used to forge these until the 1950s, but the process for making them changed, and the company switched to punching them from flat stock with a press. The punched parts would be drilled for the stud and pin holes, then put in a press to swedge the thumb pad to the proper dimension. The thumb pad would be knurled, and the entire part case-hardened.

“The material had to be soft, to facilitate all the punching and swedging,” said Norm. “We had to use low carbon, 1020 or 1018 steel, soft stuff, for ductility.” The case-hardening process later added carbon to the steel, to harden the surface of the part, but the core remained soft.

In contrast, the MIM hammer is much more robust, much harder, all the way through to the center. With the old hammer design, it wasn’t uncommon for the Warranty Department to get a gun returned with the hammer spur snapped off, but that hasn’t really been a problem with the stronger MIM part.

On the Edge

It appears that the critical surfaces on the MIM hammers also hold up better, due to their consistency and harder material.

In particular, the surface that engages with the sear holds up much better on the MIM hammer, because it’s near perfect—it’s hard and it has the proper tolerance. Whereas the old hammers were subject to wear in this area—enough so, that the hammer might begin to drop off, due to inadequate single-action sear engagement—the new hammers don’t seem to wear at all. Smith & Wesson folks tell us their edges remain hard and crisp, and the tighter tolerances guarantee that they will work as intended for a much longer period of time than the old, stamped parts.

Smooth Move

Smith & Wesson feels that the MIM parts have also improved the quality of the action, too, as a general rule.

With the old manufacturing method, the notches in the hammers and triggers were made with a fifteen-foot long broach, with the part laying on its side. The broach would leave a bunch of very small tool marks that ran horizontally across the face of the part, leaving a rough surface that looked like a series of ridges and valleys, when viewed through a microscope. These marks increased the drag and friction between the interacting surfaces, and decreased the quality of the action, making it heavier and rougher.

You could polish these out to smooth the action (and many of these old-style parts had to be polished and hand-fitted anyhow, because the manufacturing tolerances varied so much), but the polishing costs additional time and money, and it also shortens the service life of the part. When a case-hardened part (with a thin, hardened “skin”) is polished to fit it to the action, the polishing actually decreases its longevity. The softer materials underneath the surface, which get exposed with the polishing, don’t wear as well, and don’t stand up as long.

The MIM parts eliminate these manufacturing problems. They come out of the molds hard and smooth, with no tool marks on contact surfaces and no need for surface prep. Because their tolerances are tighter, they don’t need to be hand-fitted to make them work. You could stone a MIM part to improve its smoothness (and Smith & Wesson does offer some upgraded actions, via their Performance Center, where the MIM’d parts are given some extra attention to enhance their feel), but they’re already smoother than the old broached and case-hardened parts when they come off the assembly line, and Smith & Wesson believes they deliver better actions than the old parts did, out of the box.4

Fans of the old guns might disagree with that characterization, particularly if they have a smooth example in their collection, that benefitted from some talented hand-fitting, but from the standpoint of the manufacturer, pumping out seven or eight hundred guns a day, the MIM parts do a better job, on the whole, of delivering consistent, quality actions than the old broached parts did.

Better Design

The new MIM action parts are also engineered to simplify and improve the design.

In the old hammer and trigger assemblies, for example, pins were used to hold all the parts together. The sear, sear spring, and stirrup were all held in place on the hammer by pins, but the new MIM hammer was built in a way that these parts fit into special pockets and are held captive without using pins.

This is important, because these parts were frequently damaged during assembly, in the old process, when the pins were being driven into place. This scrap increased the per-unit cost, and slowed production. Additionally, it’s easy to lose these small pins when doing maintenance on the gun, so the simplified design offers an advantage, there (although armorer friends tell me it can be a little more tricky to get the pin-less assemblies back into the gun, because they lack some of the tools and fixtures that the company has).

Ergonomics

Other elements of the gun have improved as well, as a result of using MIM production.

The new-design thumb piece, for example, with its angled contact point and more rounded edges, is a more comfortable and ergonomic part than the old one was, but it would have been cost-prohibitive to build this new part using the old process. With MIM manufacturing, this complex-shape part can be made quite economically, giving the user a better control for less money.

Barrels

The MIM process has even allowed Smith & Wesson to source a one-piece barrel for the Model 36 that helps to keep costs down, and make the gun more affordable.

Parmatech MIMs the Model 36 barrel for Smith & Wesson, which is restricted to .38 Special +P pressures, only. They only make barrels for the carbon steel frame guns (the stainless and aluminum frame guns use machined stainless barrels, not MIM) because you can’t get a good color match for the stainless and aluminum frames with MIM alloys, but the MIM barrel looks right on the blued Model 36, and saves money.

The Bottom Line

This is just a sample of the enhancements that MIM parts have allowed, but it gives you a flavor for why Smith & Wesson made the leap to this new manufacturing technology.

In the view of Smith & Wesson, the new guns are stronger and better than the old guns, are simpler to make, and more economical to produce. The new MIM parts may not be as attractive as the old case-hardened and blued parts, in the opinions of some customers, but the cosmetics are still good and they’ve allowed Smith & Wesson to continue manufacturing these guns at a price that’s within reach of the consumer.

If Smith & Wesson had to keep building the guns the old way, with all kinds of hand-fitting, they couldn’t sell them for a price that anyone would be willing to pay. A new-production K-Frame revolver would probably cost you upwards of $2,000 if Smith & Wesson was still employing an army of skilled machinists, polishers and fitters to build it. The modern manufacturing methods allow Smith & Wesson to produce a stronger, easier to assemble gun, at a reasonable price point for the consumer.

Challenges

Despite the earnest attempts to improve the new guns, it’s still difficult to get many long-time Smith & Wesson revolver fans excited about them.

A lot of us have strong emotional attachments to the older guns, which are not only more attractive, but in some cases, smoother in operation, due to the hand-fitting that was required to make them work. They are also reminders of, and links to, a past that we enjoyed very much.

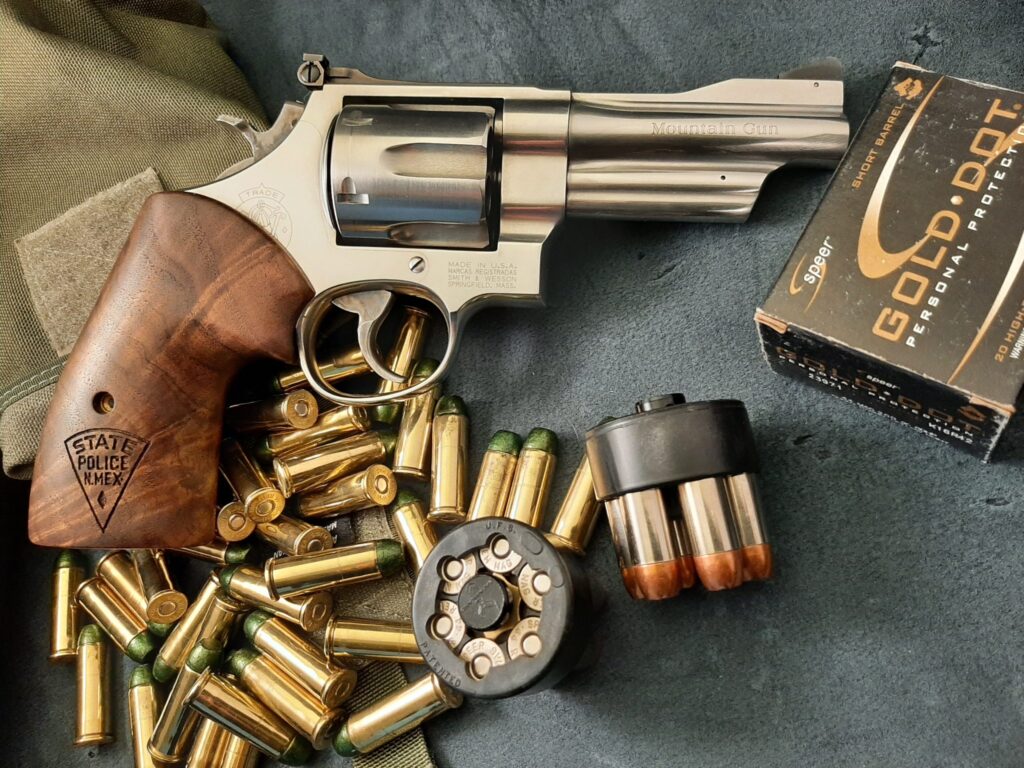

In some cases, the old guns are prized more than the MIM guns because there’s no modern equivalent. If you really loved the old Model 12 Airweight M&P, the .41 Magnum Model 58, the Mountain Guns, or the .45 ACP target guns, then you’re out of luck, as a buyer, today. There’s no MIM equivalent to these guns in the current catalog.

If you’re a gunsmith, you probably think the new MIM guns are more difficult to work on. It’s harder to cut off a MIM hammer spur, for example, because they’re made of harder stuff. If a customer wants you to remove and reinstall one of the new, two-piece barrels, you can’t, because it requires a tool that Smith & Wesson has not made available outside the factory. The new, two-piece barrel design solved a lot of problems for Smith & Wesson from a manufacturing standpoint, and has some definite advantages (which we’ll discuss in an upcoming article), but it sure makes life a lot tougher for those who work on the guns in the aftermarket.

The Elephant in the Room

Then there’s the damned lock, which crept into the guns shortly after the MIM parts did.5

We’re no fan of the lock here at RevolverGuy, and we think it’s done more to harm Smith & Wesson’s sales and reputation than they understand, but that’s a conversation we’ve already had. We won’t harp on it here, but we do think it’s reasonable that at least some of the antipathy towards “the MIM guns” is actually generated by lock hatred. The MIM improvements suffer by association with the lock, receiving collateral damage.

Some of our Smith & Wesson friends have confided that they understand the locks are still controversial, but they encourage us to not throw the baby out with the bathwater. “People can hate the lock, and I understand,” said one, “but if they had any idea of how difficult the journey was to improve these revolvers from the old to the new design, they would feel much better about the new product.”

“We made these (MIM) changes to improve the gun, not to cheapen it,” said another. “We didn’t just make these changes to save money, we honestly felt that they made the gun stronger and better.”

A Fresh Look?

I honestly haven’t spent much time with the MIM guns. I’ve shot a few here and there, but I don’t buy them, because the lock has kept me away from them.

This educational journey about MIM and the new designs has me thinking about my prejudices, though. I’ll never approve of the lock, but perhaps it’s time for me to look beyond that, and appreciate all the other good things these guns have to offer? Maybe I need to focus more on what’s right about these guns, and less on what’s not? Maybe it’s time for me to get some real, firsthand experience with the new MIM guns?

I don’t know, that’s a hard pill to swallow, but I do know that I appreciate the education I received in the course of researching and writing this series, and I hope you’ve learned as much as I have about these guns and the MIM process. I appreciate the hard work of the Smith & Wesson team over the years, and their efforts to make these guns available and affordable, so future generations of shooters can become RevolverGuys, too.

*****

RevolverGuy would like to thank Craig Mariani (the former Team Leader of the Smith & Wesson Revolver Engineering Team) and Norm Spencer (a Smith & Wesson Machinist, Model Maker, and Manufacturing Engineer) for their assistance with this project. The education they provided was critical to our understanding of MIM technology and the manufacturing changes that occurred at Smith & Wesson during their tenure. We would also like to thank the team at ARC Group Worldwide, for their information and assistance. Thank you, gentlemen, for sharing your experience and knowledge with us!

Endnotes

-

Ruger certainly made a name for itself in the casting business, but that doesn’t mean it’s overlooked other manufacturing technologies. In fact, Ruger is doing a lot of MIM manufacturing themselves, these days, and also contracts out for other MIM parts.

In November 2014, Ruger purchased Megamet Solid Metals Inc., a MIM company based in St. Louis, Missouri, to secure an in-house MIM production capability. Since that time, Ruger has been incorporating MIM parts into many of their favorite revolvers, such as the SP101, the GP100, and the new Wrangler (whose action parts are almost all MIM, which allows Ruger to offer the gun at such a competitive price).

CEO Mike Fifer stated that having an in-house MIM production capability definitely speeds up new product development. Instead of having to wait for extended turnaround times from outside vendors, Ruger can modify and improve parts and molds much faster by keeping them under their roof.

Source: Ruger’s in-house MIM Operation Increases Speed to Market For New Firearms Components

-

Our own SH Bond, an experienced law enforcement armorer who worked on these guns, says the Baker Mark III design was a definite improvement over the earlier guns, which were based on the 1892 Army and Navy. It substituted a coil spring for the more troublesome leaf spring used in previous Colt designs, and incorporated other enhancements, like a bolt that was powered by a simple mousetrap spring, instead of the Rube Goldberg arrangement that ran off Colt’s V-mainspring. From an armorer’s perspective, it was a stronger, simpler action, and easier to maintain than the traditional Colt revolver action.

Gunsmith Nelson Ford notes, however, that Colt didn’t spring the gun properly, and both the coil mainspring and bolt spring were too weak for the job. He also had several negative experiences with the compressed powdered metal parts, to include a hammer spur that broke off and struck him in the forehead during firing. Alas, the new-style parts just didn’t live up to the promise of Baker’s rugged, new design.

Both Bond and Nelson lament that Colt chose to use a modified V-spring (a “U-spring”) in their new Cobra and Python actions, wishing that they had followed the S&W/Baker model, instead. It may not have satisfied Colt purists, but it would have made for a better, more readily serviceable, gun;

-

The move towards CNC machining was also part of this industrial revolution at Springfield. We briefly touched on some of the advantages of CNC machining in previous installments, but we haven’t given it the attention that it deserves in this focused series on MIM technology. Perhaps we’ll dive into CNC in the future, but for now, it’s important to understand that the old system of building guns with human-operated machine tools was supplanted by CNC machining and MIM at Smith & Wesson during this era. These were complimentary technologies, which allowed S&W to completely modernize their methods of manufacture, and it would be misleading to ignore half the story by only mentioning MIM;

-

I’d be remiss if I didn’t note there’s a number of gunsmiths and aficionados that would disagree. There’s some very knowledgeable folks who feel the pre-MIM actions were generally better than the MIM actions, and I’m in no position, given my lack of experience with the MIM guns, to refute it. For now, I’ll simply acknowledge that it’s Smith & Wesson’s position that they’re able to produce a better, stronger action, with less expense and effort, by using MIM action parts, and I’ll leave it for the individual shooter to decide for themself if they agree. If you’ve done a lot of shooting with the MIM guns, please make sure to tell us what you think of them, in the comments, below. How do they compare, in your experience, to the guns made prior to MIM?

-

The first MIM parts started going into Smith & Wesson’s guns in 1994, with a heavy increase, year over year, from 1995-2010, and the internal lock was added around 2001. While the MIM parts beat the lock by seven years, the new additions happened close enough to each other that a lot of RevolverGuys tend to remember them as a package deal. We were just starting to recognize and digest the MIM changes when the lock was added, and over time we’ve remembered them as one big change. Heck, I guess a span of seven years is close to “the same time” when you’re talking about a design that had already been in production for almost 100 years, at that point.

Recently a friend had me look at his M460 XVR as well as his 629-3″ he bought them a few years ago and wants to sell them. I tried both of the actions and immediately noticed that the actions were tight but they have a different feel and sound than the old carbon steel lockworks. I have a 642-2 and it has mimmed lockwork, it has a decent trigger pull and letoff is stackable and predictable. Perhaps it is the size of the lock components on the N-frame and the X-frame but they have a very different sound as the components mesh together, not so noticeable with the J-frame.

I understand that S&W in order to remain competitive has to be able to make a profit and give return to stockholders. Many years ago the biggest cost was the material needed to make the firearms. Skilled toolmakers and trained machine operators do not come cheap. In todays world who knows what will happen with supply chain issues, labor shortages and general unpredictability of the future.

I thoroughly enjoyed this series having come from a manufacturing background. S&W it appears has worked out the bugs, they are making a great product at an affordable price.

TD, you really nailed it. In the Golden Era, labor was cheap and materials were expensive. In the latter 20th Century and early 21st, labor was expensive and materials were (relatively) cheap. In the current mess, labor is . . . well, in short supply, due to our own shortsightedness, and materials are also hard to get. Combine it with inflationary pressures, and we’re definitely in for some price hikes. I just hope we don’t see manufacturers slip into the malaise that we saw in the Bangor Punta years at S&W!

Absolutely agree, when I was in manufacturing, airframe bearings, we had ouside companies come in and try to streamline our processes. We were told if there are bottlenecks in your process it is either man, machine or material that was causing said bottlenecks. We were a union shop using some very old machinery trying to hold .0001 tolerances. The workforce loved overtime and prior to 2000 we were working 6 or 7 days a week. A lot of our issues were man caused issues, operators would slow the operation down once the set up people got the job running. There were also issues with old/poorly maintained machinery. We had a Blanchard grinder that should have been scrapped 30 years prior, we had multiple spindle B&S screw machines. They were only as good as the set up and the operator, if a tool got dull or broke and no one reset; it’d ruin the better part of a shifts worth of parts that needed secondary opertions before moving on in the flow.

I was sent to management training in Asheville, NC at WCI. We were told if you are running processes as you did 20 years ago it will cost the company $$$ or worse. Unfortunately, I was middle management; they needed to send the higher ups as they were the ones that could have instituted the necessary change. I tried to institute performance metrics for each of the flow paths I was in charge of but I got pushback from the union as well as my immediate supervisor. After meeting our goals for the year using tons of overtime there was a massive layoff. I stayed on for another year, the company was bought by their largest competitor also the largest producer of bearing grade steels. They came in and took what they wanted, sold all of the CNC equipment, sold the older machinery at scrap rate. They sold product line that they did not want, airframe, to our largest local competitor… Just like that massive jobs cut and another brownfield property.

S&W has changed their processes to improve profitability, to keep their pricing competitive and because their competion had already done it to a certain degree. Now they have to sell their new process as state of the art because there is a stigma of misinformation on MIM…Your article starts the education process..man, machine, material and marketing. One of the most enjoyable reads on the subject.

Holy cow, TD! After reading your comment, I feel like the wrong guy wrote this article. With your background and experience, you were the better choice to tackle a project like this. If you enjoyed it, then I feel like I must have really done well. Thank you Sir!

We had an interesting chat in the comments to Part Two of this series, about S&W’s decision to eliminate some quality assurance elements. I think the problems folks encounter with the product these days actually stem from that, and not the MIM parts themselves. It seems like they can really build an excellent gun with the current process when it works as designed, but those hiccups in Man, Machine and Materials (to steal your excellent phrase) don’t always get caught before the gun ships, because the post-manufacturing inspection process is weak. I suspect the middle managers know it, just as you understood the weaknesses in your company’s process, but convincing the suits to make the requisite change is often difficult!

The hierarchy in American manufacturing is the result of years of doing the same thing and not accepting change unless it is absolutely necessary due to market changes. I have a friend who retired from LE and went to work at Colt. He was in charge of their LE Sales. Colt had been developing a 9mm single stack striker fired pistol. He went out and made a bunch of inquiries if the potential PDs, LE agencies might be interested. He had tons of positive feed back saying yes build it we will buy it is it is good. He brought the + feedback to Management and it was thrown around for a bit…eventually being relegated to the, “Not our market”. Lack of foresight has tended to be the greatest downfall. Colt opted out of a market that is flourishing at the present time. Perhaps the best thing that happened to Colt is the acquisistion by CZ.

Colt has always relied on their bread and butter MIL contracts and they haven’t paid attention to the “civilian” market. CZ will bring Colt into the 21st century as they know both the CIV and MIL markets. I know this is off topic but things like this happen because, People refuse to understand a given market driven want, by the buyers. A start up company like Glock comes on the scene and within a few years dominates the LE market. I know S&W and several others were blind sided by Glock and its business practices..There was the necessity to change or get steamrolled. I remember buying police trade in revolvers some were under $200, K-frames; L and N frames under $400. How could S&W possibly go back to producing revolvers if the suddenly became a “niche market” and there product had been “obsoleted” by the new generation of wonder-nines? Sir, I think you have showed us how a fine company did indeed overcome the adversity of the marketplace, less need for revolvers, but still build them and remain viable in the marketplace…This series was reflective for me as I was impacted by lack of foresight and status quo attitude that was the death knell of much of legacy manufacturing in my part of New England..

I was right. YOU should have done the series! Wonderful commentary, thank you for sharing it!

Ah, Colt. Someone should do a story about them, too.

My dad was a Colt man and I wanted to follow in his footsteps, but they were busy committing suicide by the late 80s, and it was not to be. Some ugly experiences with a flawed King Cobra (the REAL one) and a worse 1911 cured me of my itch for the rampant pony, and I went to S&W (and Sig), instead, for my needs (alas, the Sig star faded by the late 1990s/early 2000s, too). Shortly thereafter, Colt turned their back on the civilian market, in another display of the poor judgment they become infamous for.

Thank goodness Paul Spitale and his team were able to turn it around, and bring some high quality Colt products back to the civilian market. I’m hopeful CZ will be a positive influence, as you suggested.

My late grandfather used to say that for any enterprise to survive, they must be dedicated to making their own products and services obsolete today before their competitors do it for them tomorrow.

I love it. What wonderful, sage, advice!

First off I’d like to say, your article made me lose some prejudice opinions I might have held on MIM-parts, though I can’t say I ever hated them, since I own an SR1911 by Ruger which has MIM-parts and works as reliable as can be.

I’m soon gonna own my very first S&W, provided everything goes well (since I live in an undisclosed country in the EU) and I gotta say: your article did really calm my concerns about new S&W production runs.

This however made me curious, since you claim that the older 686s for example use stamped hammers etc. which are weaker and can potentially be more prone to breaking.

Would you advise against buying an older 686 (or really any line) as a result, if you are limited in aftermarket parts and want a more reliable and durable S&W or would you say it’s also alright to consider older models in terms of durability of the parts and reliability?

Best regards

“I’ll never approve of the lock, but perhaps it’s time for me to look beyond that…”

Blasphemy! (or not) Thanks for another well-written, highly informative article.

Good on S&W realizing that MIM parts can be, in certain applications, an improvement over the old ways of manufacturing. Now, if they really wanted to improve their product line, ah, what’s the use.

Haha! Indeed, Bill. I can’t get them to answer emails or phone messages, so I have little expectation that they’ll listen to my advice on their product line, but one can always hope.

What an openminded investigative quest you’ve completed, Colonel Mike, one that will benefit all serious revolver guys.

This three-part series laid to rest any doubts and concerns I had about MIM technology. If made well, MIM guns parts seem to be superior in durability and function compared to the old manufacturing process. Perhaps one day savvy customers will recognize that.

Maybe I missed it in the articles, but do you have a rough idea when S & W started using MIM parts? Ruger firearms, I think, have had MIM parts for many years, perhaps decades.

Now for that cursed, lawyer-inspired S & W revolver lock and cheesy plastic firearms….

Thanks Spencer! I think the info you’re looking for is buried in Endnote #5

About 7 years ago I had two J-frames (of 2000 – 2004 vintage) fail in the same way: the hammer blocks fractured in the middle. Examination revealed a grainy looking metal at the break. At the time I assumed it was some kind of MIM or powdered metal. I replaced them with parts from Numrich which I assume were made from machined steel stock. They have been fine since. But in your diagram you don’t show the hammer block and I don’t know if S&W ever made them using MIM. A long skinny part seems like a poor choice for MIM.

Chris, the hammer block is not a MIM part, to my knowledge. Unfortunately, bad parts come in all flavors, and it sounds like you may have found some bad ones made from machined stock.

Now that I’ve stopped drooling over Kevin McPherson’s S&W Mountain Gun, I’d like to comment on the hardness of the older stamped out parts.

Gun parts that are constantly subjected to heavy impact, like the hammer on a revolver, or a bolt in a rifle, of necessity, use different grades of steels to be heat treated differently. Softer steel is ductile, takes a prolonged beating, and does not tend to fracture under stress. Anyone who has used a hammer and anvil will notice that the anvil tends to wear out more hammers than vice versa. Case hardening the soft steel in the hammers and triggers enabled them to have a soft, ductile core that could withstand thousands of dry fire and live fire impacts without shattering, yet hard enough to take a few generations to wear out. The same holds true with bolt action rifles, as an example. The venerable M1898 Mauser bolt action rifle had a receiver that had a relatively soft core, but was surface hardened. Both the receiver and bolt had this treatment to enable it to be serviceable throughout two world wars, and then some. Those who have AR type rifles will have AISI 4150 barrel extensions that mate to a bolt of Carpenter 158 (P-6 Tool Steel) or AISI 9310 riding in an AISI 8620 bolt carrier. Different steel, different heat treat, different job.

To throw my $0.01 cents worth pertaining to the lock. I hate it, I loathe it, it looks ridiculous, and I find it offensive that lawyers have been allowed into the design of firearms, but that’s another axe to grind. I’m with Mike that THE one factor that prevents me from owning any post 1998 S&W is that Hillary lock. I do have a 2006 vintage M37-2 factory DAO without the lock, complete with all MIM innards, and its trigger timing is superb.

However, having said that, I can only think of ONE scenario where that lock MIGHT be useful – a qualified ‘might’ at that. If one must of necessity (legality) leave their revolver in their vehicle, such as before going into Courthouse or other restricted area, engaging the lock prior to securing the gun in a glove box, center console, or secure device might provide some semblance of peace of mind to the owner.

Never mind – on second thought, scratch that ‘one scenario’ paragraph . . .

S. Bond,

I hate to barge in on you and Mike’s conversation- But I always appreciate your wisdom on metal parts and internal locks! Thanks for the love on my Mountain Gun, too.

Kevin, Beautiful Mountain Gun. I need to find some wood stocks for it. I have one myself but unfortunately (depending on one’spoint of view) it’s a 629-6 so it most probably has all the nasty parts plus the lock. It shoots fine so I’m quite pleased with it.

Thanks Mike!

This three part series is excellent. I, too, have passed up new MIM Smiths over the years… “but for the lock”.

Thanks Riley. There’s a lot of us, in that group. I sure wish they’d make some changes.

I have some experience in metallurgy but maybe not as much as Tec! That said that you both for an excellent series and additional explanations. I had lots for experience sintering rare earths for magnets which carried over to sintering waste material making it inert so that part of the process made sence to me. I did not understand the MIM process at all. Like most folks I associated it with the lock and inherently weaker. Flat punching and case hardening is much weaker but I assumed the hammers were forged. Eye opening number two. Again great series! If you are looking for a new Smith (I am), look at the 640 pro which has been reviewed here. While only 5 rounds it does not have a lock

Thanks Mr.Bill! Glad you enjoyed it. There are more surprises ahead, in a related S&W article that will kick off the New Year. Make sure to come back and check it out!

I’m here all the time and often refer friends to various articles/tests!

Thank you! I appreciate you sharing it with your friends!

Just my perspective, I’m “new” to the revolver world and have only been addic…..shooting them for the last 8ish years. I absolutely appreciate and love the old revolvers I only own new MIM/Hillary hole S&Ws. I edc a 686 plus and only use full house, Remington 125gr SJHP 357mag ammo to train with as well as use for self defense, I also use Buffalo Bore 125gr jhp, Double Tap 125gr jhp etc., I have at least a few thousand rounds through it and the revolver has been nothing short of great and reliable! I have a few others including the new Model 27, 19, 627 Pro and these too are brilliant and beautiful revolvers! I may very well be missing something from the past due to ignorance or just not being around, I lived in communist NYC until 10ish years ago, enough of a variety of older revolvers except for a short stint with the NYC Housing police and the Model 10/64, and various snub nosed revolvers, were my only knowledge of older revolvers. I’m not pro or anti MIM however I just haven’t had any issues that would keep me away….even with the dreaded Hillary hole. Anyway I always look forward to reading anything on this forum and y’all are a great source of information. Thank you

Great series! On the (darn) locks, recall that Saf-T-Hammer Corporation bought S&W in 2001. STH was a revitalization of a defunct mining operation De Oro Mines Inc (2001 10-K filing) which had pretty much only one type of product (the patent-pending Saf-T-Hammer and Saf-T-Trigger systems) that they planned to license across the industry. The President of STH was Bob Scott, who had been at S&W as a VP. When the backlash to the Clinton Settlement Agreement of 2020 drove S&W into the ground, STH bought S&W and declared they would incorporate their locks into S&W guns for $12 per unit (LA Times 5-15-01), $12 per unit in a manufacturing environment in 2001 seems a bit high. Perhaps STH executives were receiving a royalty? Perhaps that’s why the locks still exist today? Although a lot of folks think the lock remains due to the 2020 settlement agreement, S&W has put to the side many of the other conditions in that settlement agreement (Exhibit 10-4 in STH 2001 10-QSB). I don’t like the lock, for both visual and practical reasons (it’s been awhile, but, in the early days, the lock was shown to engage itself sometimes in the lightweight heavy caliber Scandium guns- happened to Michael Bane on film if memory serves- I can’t forget that issue) but it might be possible it remains due to reasons other than lawyers. Considering the weird executive issues at S&W in the early 2000s, and that there has always been a holding company structure, it is possible (but not proven by anything I’ve seen yet) that locks remain for financial reasons for a select few from the buyout days. Interesting idea at least, since Ruger and other makers have trimmed down the installed safety devices in many of their lines (as has S&W with magazine disconnects and manual safeties in the auto pistol line). Let’s just say it is a possible explanation why S&W doesn’t much talk about wheelgun locks and is happy to let them be called “lawyer locks”.

I wouldn’t doubt it, Sir. Follow the money!

These write-ups never cease to impress. Thanks for continually being the definitive source I link to when I’m speaking of revolver concepts lately.

Thanks for the praise, Zach! I’m glad we’ve earned your trust!

I greatly enjoy and learn from your website. Thank you!

I have a S&W 686 SSR. As I recall it was advertised as having a forge hammer and trigger, not MIM. This feature was highlighted as being more durable than MIM. If true that would seem to be in conflict with S&W claims that MIM parts are more durable.

Best Wishes.

Glad you’re enjoying the site, Michael. I don’t see that claim being made in the current marketing for the 686 SSR revolver on the S&W site, and I’d be surprised to discover they were forged parts, based on the appearance of those parts in the catalog photos. I can’t accurately comment on what they did in the past, because I don’t know, but I will say that if they played up the “forged parts” angle, it was probably to counter unfounded consumer opinions about the strength of MIM parts—tell the customer what they want to hear.

Excellent series on MIM. Until now my only experience has been use in electrical power components. With regard to Michaels Kobe’s message on the 686SSR, I recently purchased one and recall reading two different gun store descriptions that stated it came with forged hammer and trigger. Obviously, this could be just a copy and paste from some very early catalog description but I found it interesting that someone else noticed it.

Thanks Rick, I’m glad you found the series and enjoyed it. I don’t know how the 686SSR is equipped, but it’s pretty easy to tell if your action components are MIM or forged, on inspection.

From a review by Jim Grant (gun.com) 8/27/2014.

“ Where most modern Smith and Wesson revolvers use injection molded triggers and hammer, the SSR utilizes a more traditional, hammer-forged trigger and hammer. While unimportant to most shooters, it adds longevity to both pieces and under normal conditions, will likely outlast the average shooter and whomever inherits it.”

Mike, it was from information, like above, that I came to believe that S&W saw forging somewhat more durable over MIM. A 2014 review would have been an early writing. I’m not trying to be contrary and I don’t know for certain what the facts are. I relied on multiple reviews I read that claimed 686 SSR hammers and triggers were forged, not MIM, for better durability as the SSR was designed for revolver competition. It may be, as you suggest, that I and others were deceived. It may also be that improvement in the MIM process has indeed made today’s MIM hammers and triggers more durable than forged hammers and triggers in early production of SSRs. Again, I greatly enjoy and respect the information you provide, and have benefited immensely from reading your website. I also bought your book on the Newhall Massacre and was super impressed by your examination.

Best Wishes,

Thanks Michael, that’s good information, and I appreciate you sharing it. I was unaware that the earlier SSR guns were using forged parts. It appears they are not, any longer, if the website is complete and accurate. I’m not sure when that changed, but perhaps another reader can enlighten us?

S&W began using MIM in 1994 and expanded its use for the next 16 years, with the transition complete in 2010. I think it’s safe to say that S&W, the industry, and consumers were all still learning a lot about MIM in 2014, so I’m not surprised to see claims from the period that forged parts were stronger. Based on what we knew at the time, and the quality of the early MIM parts, that might have been a reasonable belief.

But the MIM landscape has changed a lot since then, and so has our understanding of it. I would not rate the old style forged parts as superior to today’s MIM parts, with the exception of their appearance. The MIM parts are harder throughout, and more robust, than the surface-hardened, forged parts of yesteryear. They are also more consistent in their dimensions. The older ones looked nicer, with their case hardening, but they simply weren’t as tough or as consistent as the new ones are.

Glad you discovered the Newhall book. There’s still a lot of lessons we can draw from that terrible experience. I fear that LE has already forgotten most of them, and a new generation will have to learn them the hard way, again. The “New Newhall” looms ahead, in the distance.

Thanks again for writing, and rest assured, I never thought you were being “contrary.” We encourage rigorous discussions here, and the challenging of ideas. That’s how I learn!

Mike,

Just curious….that is a great photo of that stainless Mountain Gun by Kevin McPherson, but I’m curious what kind of ammo it’s perched on… those look like Speer .44 mag hard cast loads, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen green bullets before? Just wondering if those are handloads or what. Maybe it’s the Irish in me, but green bullets seem pretty novel! LOL!

Hey Shane, thank you for liking my photo! Those loose rounds are indeed handloads. That Mountain Gun is zeroed with a 200 Grain Gold Dot handload that usually just breaks the sound barrier. I started using cast 200 grain Round Nose Flat Points for a practice load to match that zero. On a max charge of Hodgdon Trail Boss with standard primers in a magnum case, that load is exceptionally pleasant to shoot and easy on the gun. it still generates over 800 fps from the Mountain Gun, so it’s not a gallery load. The RNFP’s load swiftly and surely into charge holes, I used them for shooting qualifications with the Mountain Gun back in the day. The green bullets are a coated version I bought from a shop in Roswell NM a while back. The caster was local and used various colors when baking on the coating. I’m a big fan of coated cast RNFP’s for all the revolver calibers I shoot.