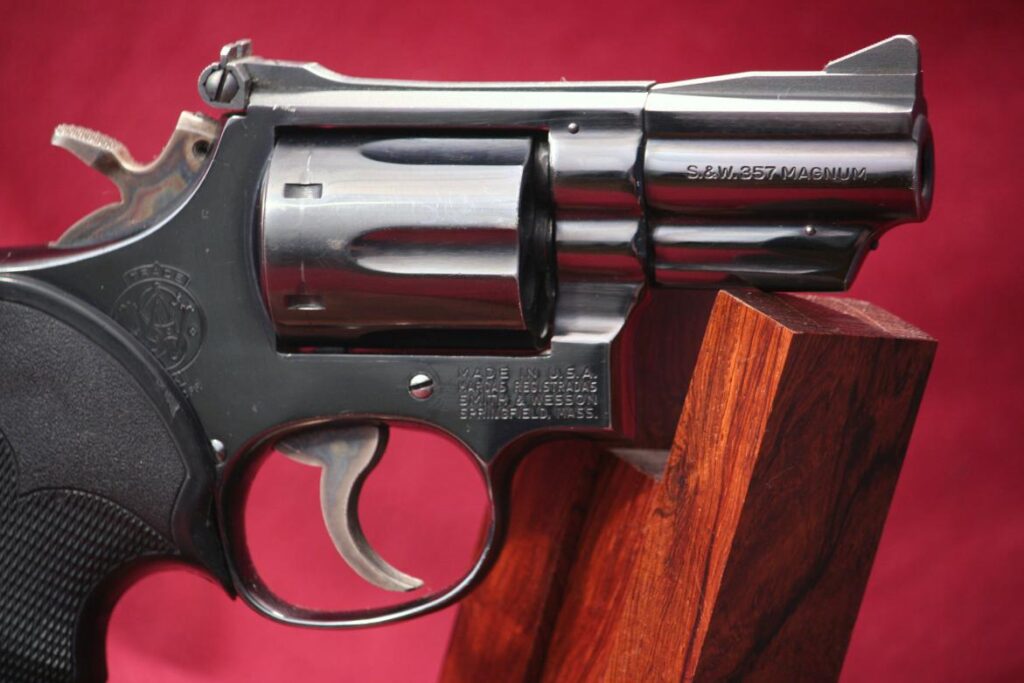

When Smith & Wesson released its first, K-Frame, .38 caliber Hand Ejector model in 1899, it’s doubtful that anyone in Springfield thought the basic design would last for over a century.

Yet, it has. Today’s Smith & Wesson revolvers may differ from their Hand Ejector ancestors in numerous ways, but at their core, they retain the design, features and function of those early arms. Your great (great?) grandfather would be right at home with a current production revolver in his hand, and wouldn’t need any instruction in its manual of arms.

Could we say the same about a modern automobile or telephone? Not likely.

Editor’s Note: It has probably felt like “The Smith & Wesson Channel” around here, lately, but it took a lot of work to lay the groundwork for this article. We couldn’t discuss the evolution of S&W revolvers without referencing MIM, and that technology was so poorly understood by most of us, that it was important to crack that nut, first, in our detailed, three-part series. Now that we understand the complexities of MIM manufacturing, we can dive into “the rest of the story.” We think you’ll find the long journey was worth the effort. –Mike

Evolution

The product has remained remarkably consistent in the most fundamental ways for 123 years (and counting), but that doesn’t mean it hasn’t changed.

Smith & Wesson engineers have made continuous changes in materials, design, and manufacturing that have altered the basic platform from its earliest days. These changes have been made to enhance the performance, strength, and affordability of the gun, and while some have been quite obvious, others have been more subtle.

We discussed some of these changes in our recent, three-part series on MIM, but as dramatic as some of those design, materials, and process changes were, they represent just part of the efforts that have been made to keep the revolver in production. There have been many other changes—some visible, some hidden—which have been made that deserve our attention here, so let’s spend a little time behind the factory doors, and under the side plate, to look at them.

Genesis

This topic has its roots in my conversations with members of the Smith & Wesson team, who worked in Springfield over the span of four decades, and were part of the Revolver Engineering team that started an industrial revolution, of sorts, in the 1990s and early 2000s, when Smith & Wesson adopted Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machining and Metal Injection Molding (MIM) manufacturing.

These new technologies replaced an old-world manufacturing system that relied upon large numbers of skilled workers, who machined parts by hand and assembled them (with some skilled hand-fitting) into firearms. These earlier guns had their fair share of flaws, but Smith & Wesson did such a nice job, overall, with them, that they captured the hearts and imaginations of three or four generations of RevolverGuys.

Unfortunately, the dedication of the consumer to these (now classic) guns posed a challenge for Smith & Wesson when it came time to upgrade their products and manufacturing processes near the end of the 21stCentury. When the company started making their products differently, and changed many of their features to accommodate the new manufacturing methods, many of their most dedicated customers were unhappy. They liked the “old ways,” and didn’t want things to change. Many of them rejected the new guns as being inferior to the old guns—sometimes for objective reasons, but often for subjective reasons.

Frustration

In the course of our conversations, the Smith & Wesson family members expressed their frustration with contemporary comments about the quality of current production S&W revolvers, versus those of years past. “There’s a strong, but mistaken, belief out there that the old guns are much better than the new ones,” noted one of the workers. “The old guns were different, but not necessarily better,” he insisted. “I spent 35 years trying to make those guns stronger and more reliable, and I think that most people just don’t understand the improvements that we made to them.”

That sounded like a challenge, and we were ready to accept it and give our friends the chance to explain what they meant by it. With their help, we started to map out some of the improvements that occurred during their tenure at S&W, and it didn’t take long before some of our own beliefs about the “old guns” were exposed. Some of the things we thought were true, turned out to be incorrect—perhaps more a product of nostalgia, than technical accuracy.

So, we’d like to invite you along for a short journey while we catalog some of the changes that have been made along the way to today’s Smith & Wesson revolver. We think you’ll be as surprised as we were, at some of the discoveries.

Post, Post-War

First, to be clear, we need to specify that we’re talking about changes that occurred in the latter part of the 20thCentury.

Major changes like enhanced frame materials and heat treating (1930s-1940s, then again in the 1970s), the addition of the hammer block safety system (1944), and the development of the “short action” (1948), had already occurred in the years prior to the era that we’re talking about. So had smaller changes, like the elimination of the upper sideplate screw (1955) and trigger guard screw (1962).

Additionally, items like the reversal of ejector rod thread patterns (1961), to remedy the issue of the rod unscrewing as the cylinder turned, and the movement of the gas ring from the cylinder to the yoke (1974-76), and back again (1977) were fait accompli.

Building Blocks

Perhaps the best place to start in our journey is with the raw materials that S&W uses to make their guns.

In the early days, Smith & Wesson used carbon steels exclusively to manufacture their guns. The raw stock would come in the door, get heated in a furnace to soften it, get cut into smaller pieces, and go into forges, where it would become gun parts. In those early times, parts like frames and cylinders would receive different levels of heat treatment, depending on the caliber of the gun.

By mid-century, Smith & Wesson had made many changes to this process. In 1951, aluminum alloys joined carbon steel, adding the first “Airweight” revolvers to the catalog, and in 1965 S&W produced its first stainless steel revolver, the Model 60.

Additionally, by the late 1970s, differential heat treating was on its way out, and all frames (both Magnum and non-Magnum) were being hardened to the same standard.

There were more changes to come in Springfield. By the late 1990s, stainless steel had supplanted carbon steel as Smith & Wesson’s standard gun-making material (“we now use it for everything, inside and out”), and the raw stock was being electrically heated before it was cut, enroute to the furnace. All the stainless frames, regardless of caliber, were being heat-treated in a vacuum with a computer-controlled process that produced more uniform results, and only the few remaining carbon guns in the catalog were being heat-treated with the older, austemper process that involved heating steel in a liquid salt bath, then quenching it.

Serendipity

One of the biggest material changes came with the introduction of new aluminum alloys, using elements like titanium and scandium. Smith & Wesson had made aluminum-framed J and K revolvers in the past, but they were limited to .38 Special pressures, only. The company couldn’t chamber them for .357 Magnum, and wanted a way to do that in a lightweight frame. This led the Revolver Engineering team to search for a solution, and they found it in an unlikely place.

It happened that the Russians were mixing small traces of scandium with aluminum, and using the resulting, stronger alloy in their aircraft. Their success attracted the attention of some U.S. baseball bat manufacturers who were trying to remedy the problem of college ball players breaking their all-aluminum bats above the handle. They found the new alloy was perfect for their use, as well.

A member of Smith & Wesson’s Marketing team was visiting with friends in the Revolver Engineering department one day, and mentioned reading about the super alloy that powered Russian aircraft and American ball bats, and lightbulbs went on in several engineering minds.

The Engineering team immediately sourced some of the alloy and began to experiment with it. They found the scandium-aluminum alloy was strong enough to withstand .357 Magnum pressures. Adding just two percent of scandium to the aluminum alloy would double its strength, but maintain the lightweight properties of aluminum that Smith & Wesson wanted to retain for their Magnum “Airlites.” “The guns were strong and light, but they weren’t fun to shoot,” said one of the engineers, who actually injured his hand during testing of the first prototype.

Computer Revolution

Not only was Smith & Wesson moving towards new materials during this era, they were shifting towards new manufacturing processes.

We’ve previously addressed the MIM revolution that occurred inside S&W in great detail, so we won’t repeat that story here, but there was an equally revolutionary change that occurred in Springfield with the introduction of CNC machining.

CNC machining not only introduced a level of precision and consistency that was previously unattainable, using the older, manual machining methods, it also had a dramatic improvement on manufacturing efficiency. For example, in the old days, a revolver frame would have to be loaded into fixtures and machines a total of 105 different times, to complete the required machining operations. It took a lot of time and energy to move the frame around the factory floor to accomplish those 105 loads, but with the introduction of CNC machining, that frame would only get loaded a total of ten times, into a pair of machines that were self-monitoring, self-correcting, and didn’t need a lunch break.

The resulting improvements in efficiency, cost, and quality control dramatically changed the landscape of the factory floor, and allowed S&W to manufacture products at a competitive price. While RevolverGuys might feel nostalgic about older methods of production that involved a lot of skilled labor, the change to CNC machining eliminated scrap, guaranteed better tolerances, and saved significant labor costs that would have otherwise priced S&W revolvers out of today’s market. “None of our customers would want to pay what it would cost to build a S&W revolver the old way, today,” observes one of the team members, “especially because the product wouldn’t be as good—the new guns are much stronger, more consistent.”

Sacred Cows

There’s a lot of RevolverGuys who would chafe at the notion that the modern guns are better than the old classics, pointing to features that are absent on today’s guns, like pinned barrels and recessed chambers. Certainly, those now-missing features make the older guns better, right?

Not really, according to the folks we talked to. The recessed, or counterbored, chambers may have had some utility in the days of balloon-head brass, but had outlived their usefulness with modern, solid-head cases. A recessed chamber simply hides the head of the cartridge, they explained. Since the cartridge headspaces off the extractor, not the counterbore, they are mostly cosmetic and don’t add any strength. They do create a trap for debris that could prevent a cartridge from properly chambering though, and they add expense, so they were eliminated as unnecessary.1

The pinned barrels were another cosmetic feature that had lost their utility over time. The pins may have contacted the barrel in the pre-war years, to help prevent the barrel from unscrewing from the frame, but after World War II, the pins no longer touched the barrel.

In the 1930s, the barrel and frame were drilled as one, after the barrel had been installed and adjusted for top dead center, and the pin was inserted into this hole to keep the barrel from unscrewing. But that’s not how the guns were being made by the 1950s. By that time, the barrels were being made with a clearance cut on the top that made it easier to drive a pin through the frame (especially if the barrel wasn’t properly clocked), and the holes were already drilled in the frames before the barrels were ever installed. The assemblers just tapped the pin in, often after giving it a little bend, so it wouldn’t walk out of the sloppy holes in the frame.

The pins didn’t make any contact with the barrel, didn’t serve any function at all, by the 1950s. Even the engineering drawings showed that the pins didn’t touch the barrel—there was no combination of acceptable pin, hole and barrel flat tolerances that allowed them to actually touch. The pins missed the barrels by 0.030 inch, allowing the barrels to turn underneath them—the very thing they were designed to prevent.

One thing the pins did do, however, was create a lot of problems. By the 1980s, the number one reason for scrapping a finished frame was the damage incurred when a mistake was made, while pinning the barrel. “The assemblers would have a bad fit, and have problems driving the pin in, and they’d strike the frame with the hammer, by mistake,” said one of our interviewees. “Either that, or they’d ream out the holes with a drill to ease the installation, and bugger up the frame.” Sometimes the damaged frames could be repaired and refinished (adding time and expense), but oftentimes they were so damaged that that had to be scrapped, which was both costly and wasteful.

To remedy this problem, the Revolver Engineering team was directed to eliminate the troublesome, useless, and costly pin entirely. They did it by continuing the barrel flats for two years, but stopping the manufacture of pins and frames with pin holes immediately. This would allow S&W to use up their existing inventory of parts, and when the flat-top barrel supply was exhausted, they could switch to making barrels without them.

Dedicated fans and collectors may like them, but the honest truth is that, over time, the pins had become useless, and the guns were better without them.

A Barrelful of Changes

The pins weren’t the only change to the barrels in this era. In fact, the Revolver Engineering team did a lot of work to improve the launch tubes during this period at S&W.

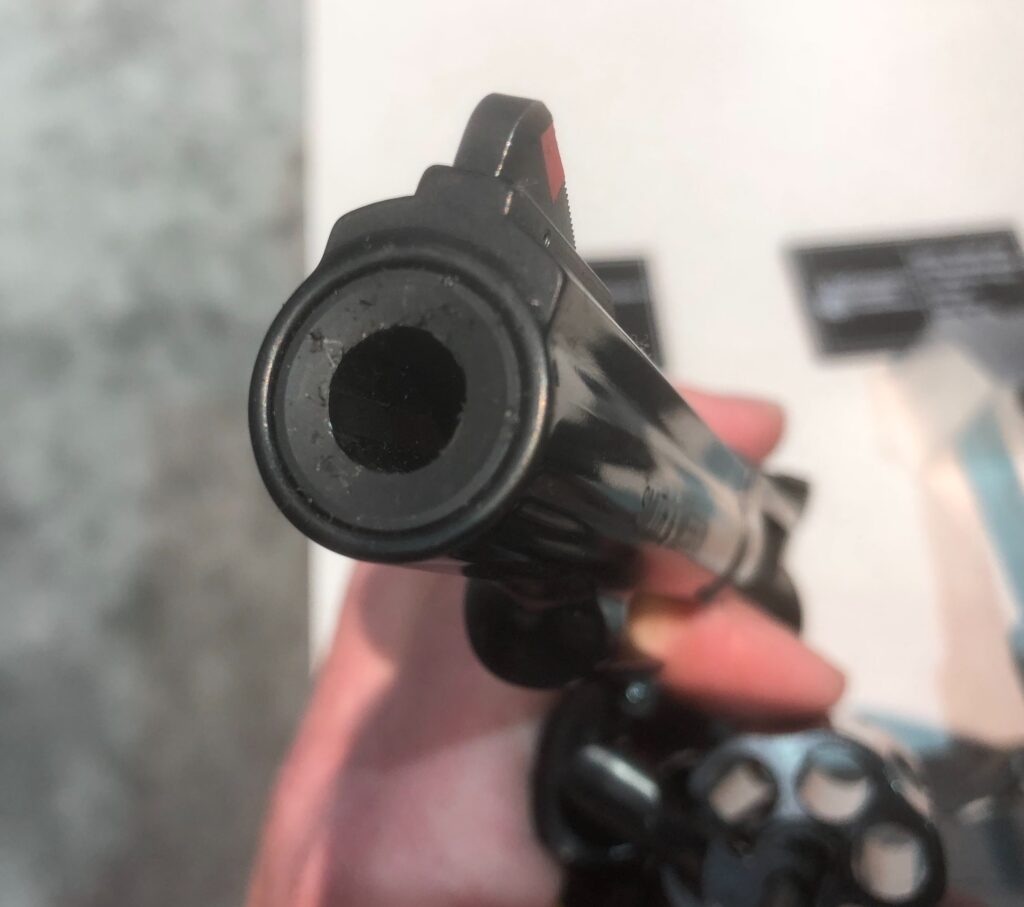

As we’ve previously discussed here, in these pages, one of the big difficulties with revolver barrel installation is getting the front sight “clocked,” or timed, so that it rests at “top dead center” (TDC) when the barrel is installed to the proper torque value. If the barrel or frame threads are just a bit off, or if the shoulder on the barrel or the face of the frame are just a little out of spec, the barrel may stop too early or too late when it’s getting installed, leaving the front sight off kilter. This is more than just a cosmetic problem, as it influences where the gun will print, and may throw the shots wide enough, that rear sight adjustments cannot bring the groups back to center.

From the earliest days at S&W, barrels were installed by hand, using a fixture to hold the frame and a wrench to screw the barrel in. Since it was done by hand, there was a fair amount of potential for human error, as the assembler tried to time the front sight on the tight-fitting parts. Too little torque would allow the barrel to start backing out of the frame on its own after the buyer started shooting it, and too much torque would stress the thin, threaded walls of the frame, and lead to a crack that would kill it. Getting it right was a difficult process, and also led to a lot of back and arm injuries for the workers. The company didn’t get to use a person in that role for very long, because the potential for a worker’s comp injury was high.

This risk increased with Smith & Wesson’s migration towards stainless steel as their go-to material for building guns. The galling properties of stainless steel increased the engagement between barrel and frame, and increased the force required to turn the barrels into the frames.

In an effort to improve the process, and guarantee a good, TDC installation at the proper torque, without hurting the workers, the Revolver Engineering team developed a new process and tooling to install the barrels. While factory workers used to tap the frames via a lead screw tapping process, and install the barrels by hand with a wrench, the Engineering team changed the process so that they milled the threads on the frame, and installed the barrels with a hydraulic machine. Pressure switches would stop turning the barrels when a torque limit was reached, which would prevent cracking the frames.

This new installation process was introduced around 1993 for the J-Frames, and migrated to the other frames over the next five years or so. The engagement of the threads was much greater with the new process, and the friction was dramatically increased, so it takes a lot more force to install and remove barrels that were assembled this way. Aftermarket gunsmiths who worked on the guns didn’t necessarily appreciate the changes, as they made it difficult to pull barrels without damaging frames, but from the manufacturer’s view, the new installation process was a winner, delivering more consistent results while decreasing injuries and claims.

A Two-Piece Suit

The new hydraulic barrel installation process was an improvement, but dissatisfaction with continuing TDC issues soon had the Revolver Engineering team looking for a better solution.

By 1995, they had determined that manufacturing the barrel in two pieces would provide an excellent solution for their troubles. The two-piece barrel concept had previously been used quite successfully by rival Dan Wesson, where they developed a reputation for excellent accuracy, even if they were a bit cosmetically-challenged.

The team thought they could do a better job of it though, and started looking at options. They considered installing a thin barrel into the frame first, then trimming it and installing a shroud around it, but this was too difficult and not a good manufacturing solution.

Putting a little more thought into it, they came up with a patented solution to use the rifling of the barrel as a gripping surface for the wrench that would be used to turn the barrel into the frame. There are six surfaces with square shoulders inside the barrel, and the wrench fits them tightly enough to complete the install.

In practice, an outer shroud that looks like the “barrel,” with front sight integrated, is attached to the frame first, using a “key” on the rear face, that mates into a matching recess in the frame. The key ensures the shroud is properly timed, and the front sight is TDC. After the shroud is installed, a small barrel “sleeve” is screwed into the frame, using the wrench that grips the rifling to turn it. The stainless barrel sleeve has a slightly belled end at the muzzle, which bears on the front of the shroud, locking it into place.

There are many benefits to the two-piece barrel design, besides fixing the critical TDC issue. The risk of creating stress risers and cracking a frame by over-torquing the barrel is eliminated, and a variety of shroud designs can be used, allowing the manufacturer to change the cosmetics of the gun (full lug, half lug, different sights, different shroud profiles and colors—including colors that match the frame, which has been a struggle on the Airweights, since the stainless barrels don’t neatly match the aluminum frames) quite easily. The 410 stainless steel barrel sleeve will resist corrosion much better than a traditional carbon steel barrel, and the lack of a dedicated barrel nut (as on the Dan Wesson design) improves the cosmetics of the arrangement.

Significantly, the two-piece barrels also seem to have a greater inherent accuracy than the traditional, one-piece barrels. The tensioned nature of the barrel sleeve apparently dampens barrel harmonics, and allows the thin barrel to throw its slugs with greater accuracy.

Aftermarket gunsmiths don’t like them, because they lack the special wrench to remove the rifled barrels, and some traditionalists don’t like them for cosmetic reasons (a thin seam between barrel and shroud is visible on the muzzle end), or because they’re just cranky about change (guilty, as charged! -Mike), but a retired team member insists, “if the customer understood all the reasons why the two-piece barrels are so clearly superior to the old one-piece barrels, they would want all of their barrels made like this!”

The Wheel Turns

The heart of a revolver, the cylinder, didn’t escape the attention of the team, either.

In the old design, the cylinder’s extractor star closed over two alignment pins that were pressed into the cylinder. These pins, which were located in the cylinder relief underneath the star, served to help align the extractor star with the cylinder chambers, and support the star. Unfortunately, the pressed-in pins could work loose and fall out. When that happened, the round extractor rod shaft could unscrew as the cylinder turned, which could tie up the cylinder, or even cause the whole assembly to come apart.

Smith & Wesson engineer Dick Mochak improved the design by CNC-milling the extractor tunnel in the cylinder with a square flat, giving it a “D”-shape, in profile. This prevented the shaft from turning in the tunnel, and allowed S&W to eliminate the troublesome alignment pins for the extractor head. There were no pins to lose, and the extractor rod would no longer work itself loose, with the improved design.

An additional benefit to the new system is that it made it easier to replace the extractor, if it was damaged.

An additional benefit to the new system is that it made it easier to replace the extractor, if it was damaged.

In the old manufacturing process, the alignment pin holes were drilled with the extractor and cylinder as a matched set. As a result, each extractor was essentially “custom fit” to its cylinder, and if it became necessary to replace the extractor, it could be difficult to find one that fit the existing pattern of the alignment pins (which were never drilled exactly the same, from gun to gun, due to manufacturing tolerances). If a good match couldn’t be found from a supply of replacement extractors, through trial and error, one might have to be modified to fit the old pin pattern. Either that, or an entirely new cylinder and extractor assembly would have to be installed.

The improved, Mochak design made this repair much less complex and expensive. The cylinder and extractor are no longer “married” during manufacture, and are just built to exacting tolerances. If an extractor gets damaged, any replacement part should fit the CNC’d cylinder, as they’re all built to the same specs.

The cylinder yoke assembly was improved as well, from a two-piece unit that was pinned, then welded together, to a one-piece unit that is CNC machined from a single piece of stainless steel. In the old style, the pieces were forged and machined, and you had to drill one piece in order to pin it to the rest of the assembly, then silver solder them together. The assembly was pretty strong, but there were still occasional issues with breakage, they were difficult and expensive to make, and sometimes the tolerances weren’t right after assembly, and the piece had to be scrapped because it wouldn’t fit properly in the frame. With the new, CNC-machined, one-piece style, the tolerances are much tighter, the part is much stronger, and there’s less effort and waste involved.

One other cylinder-related improvement is more subtle, but still very important. The lug on the frame which prevents the cylinder from sliding aft, and off the yoke barrel, used to be a separate piece, which would occasionally come loose and tie up the gun. During manufacture, the frame would be drilled for the lug, which was inserted into the side of the frame, then cut and shaped, so the cylinder would pass over part of it, then stop. When it worked loose from the hole, you had a big problem. Nowadays, thanks to the efforts of Revolver team member Richard Mikuta, the cylinder lug is cut as part of the frame. There’s nothing to come loose, and the gun is much stronger for it.

Framed

The frames have received several notable improvements, as well, over the years.

The hammer studs on the steel frame guns are much stronger now, than they used to be. In the old design, the stud had a collar at its base, just above the threaded part of the shank that screwed into the frame, and the stress risers would occur at the square corners between the shaft and collar, leading to the hammer stud cracking and breaking off. In the new design, the stud has no collar, but instead has a pin inserted through it, where it meets the inside of the frame wall, and the pin is copper brazed in place. With no stress riser at this spot, and a strong weld in place, the steel frame hammer studs are very robust now, and it’s rare for them to break.2

Those of you who are fans of the flyweight, J-Frame scandium Airlites are familiar with another frame improvement that resulted from the team’s efforts—the stainless steel frame insert at the top of the cylinder window, just above the forcing cone. They patented the insert, which is designed to minimize flame cutting of the scandium alloy frame with hot Magnum loads. Whether or not anyone is brave enough to fire a sufficient number of Magnum rounds through the 12-ounce blaster to damage it is another question, but it’s there, if you want to try. The stainless shield can also be found on the .357 Magnum, L-Frame Model 386, and the .44 Magnum, N-Frame Model 329 for the masochists who’d like to try and wear one out.

One last frame change that we’ve addressed previously was Smith & Wesson’s decision to standardize on the round butt (RB) frame, starting in 1995. We personally miss the square butts here, but there’s no doubt that moving to a single frame profile simplified manufacturing and logistics for the company, which (theoretically, at least) resulted in efficiencies that reduced prices for the consumer.

Parts Is Parts?

We talked about it in the previous installments on MIM, but we’d be remiss if we didn’t mention the improvements in the triggers and hammers that resulted from using the new manufacturing process, starting around 1997.

By that time, the hammers and triggers hadn’t been forged for about 40 years. Around the 1950s, Smith & Wesson started punching out triggers and hammers from flat stock with a press, instead of forging them. The punched parts would get drilled, and the hammers would get placed into a press to swedge the thumb pad to dimension and knurl them, then the parts were color case hardened, to put a hard skin on them.

These parts were soft inside, though, because the raw material had to be soft to facilitate punching and swedging. Smith & Wesson used 1020 or 1018—soft, low carbon steel—to allow the swedging and maintain ductility, so the high stress parts wouldn’t be brittle.

Unfortunately, the broach that cut the notches in the stamped hammer and trigger would leave a rough surface behind. “Under a microscope, you could see a bunch of ridges and valleys running across the parts, perpendicular to their arc of movement. The tool marks looked awful, and left the contact surfaces rough, where you wanted them smooth,” said one of the team members.

With the new MIM manufacturing method, there are no toolmarks left behind on the action parts, which are smooth and hard from the start. “The MIM hammers and triggers give a better factory action from the start,” we’re told. “They’re much smoother than the actions made with the old, broached and case-hardened parts.”

The new (circa 1997) MIM hammers have proven to be more robust than their predecessors. Moving the firing pin (“hammer nose”) from the face of the hammer, to the frame, as part of the redesign, dramatically reduced the number of firing pin failures. Additionally, the new MIM hammers have escaped the indignity of having their thumb pads snap off, which sometimes happened with the swedged hammers.

The colors of the new MIM triggers and hammers are not as attractive as the old case-hardened parts, but they’re generally smoother and much stronger, and Smith & Wesson thinks that’s a pretty good tradeoff.

Better Designs

Aside from all the individual nuts and bolts, there’s some genuine design improvements that have crept into the guns over time, as well.

Consider the latest iteration of the classic, Combat Magnum. Today’s Combat Magnum lacks the Achille’s Heel of the old gun—a barrel flat for yoke clearance that led to the older forcing cones cracking under a steady diet of 110 and 125 grain Magnum loads. You can shoot all the barn burners you want to in today’s K-Magnum, and it will just laugh them off. You’ll wear your hand out before you break the gun.

The new Combat Magnum does away with the forward locking bolt for the extractor rod, as well. Instead, the forward lockup occurs at the yoke, which is arguably much stronger, and eliminates the problem of an extractor rod unscrewing, and tying up the gun.

Too, the elimination of the forward locking bolt allows the use of a full-length extractor rod on the short, 2.75” versions of the gun, because there’s more space up front in the hollow of the lug. This makes it easier to clear spent cases from the new gun than it was on the older versions of the snub Combat Magnum, which had shorter extractor rods underneath their stubby barrels.

As much as I love my old Combat Magnums, I have to admit that the new versions are designed better, in many important respects.

Yikes, did I just say that out loud?

A Solid Case

We have to admit that the Smith & Wesson team members we spoke to made a pretty good case for the current production guns, and we were surprised to see how some of our strongly-held beliefs about the old guns didn’t hold up under scrutiny.

To many eyes, the new guns are less attractive than their forebears. The matte stainless finishes and blackish bluing found on the new guns don’t compare to the polished stainless and deep blues of old, and the case-hardened hammers and triggers of the old guns look better than the new, gray MIM parts. It also seems the older wood stocks, made in-house, were more shapely and attractive than the versions which have been sourced to equip today’s “Classic” line of S&W revolvers.3

Then, there’s the lock. We’ve already said our piece about that, and won’t belabor it here, but the lock does take away from the appearance, reliability, and acceptability of the new guns. Terminally so, for many RevolverGuys. ‘Nuff said.

However, if we can put those things aside, we’ll find there’s a lot to like about the new guns. They still have good looking lines, are attractive in their own right, offer improved features, and they’re a lot stronger than the old guns. They may not gleam like the old ones, but Smith & Wesson says they’re tougher, more consistent and will last longer.

They’re also affordable. You couldn’t buy a Smith & Wesson at today’s prices if they were still making them the old way. Would you be willing to pay upwards of $2,000 for a regular K-Frame? Probably not.

I refer again to the words of one of the team members:

If the customer had any idea of how difficult the journey was to improve these revolvers from the old to the new design, they would feel much better about the new product! We made all these changes to improve the gun, not to cheapen it. We didn’t make these changes just to save money, we made them because our customers use these guns to defend their lives, and they have to be durable and reliable. They have to work when it counts!

Thanks

So, on behalf of RevolverGuys all across America, we’d like to thank them and their fellow Smith & Wesson family members for all they’ve done to ensure these guns will be around for future generations to enjoy.

*****

Endnotes

-

Armorer Dean Caputo argues that recessed chambers might actually serve a role in protecting the ratchet on the extractor from getting battered, as the revolver develops endshake over time. Cylinders with recessed chambers are built slightly longer, with a raised rim around the circumference of the rear of the cylinder, to surround the rim of the cartridge’s case. This extended rim may contact the rear of the frame window first, as the cylinder moves aft under recoil, bearing the brunt of the impact and saving the ratchet from unnecessary damage;

-

Alas, the aluminum-framed guns are more of a difficulty. You can’t copper braze aluminum, so the aluminum hammer stud is made with a collar on it, like the old design, and it’s staked in place to hold it securely. Since aluminum is a weaker material, the hammer stud is more likely to break on the aluminum guns, which is simply one of the costs associated with making a gun from the lighter and less expensive material. Fortunately, a titanium hammer stud can be used on the scandium alloy guns, which makes them as robust as the stainless and carbon steel-framed guns;

-

For that matter, the wood stocks that were standard on the older guns were more attractive than the rubber stocks found on most S&W revolvers today, but you can hardly blame S&W for that, as it was consumer demand that forced the change. Back when revolvers were all shipped with wood stocks, it was popular to yank them off and replace them with aftermarket rubber stocks from Pachmayr, and others. Now that revolvers are generally shipped with OEM rubber stocks, it’s popular to yank them off and replace them with aftermarket wood stocks. Smith & Wesson gave the customer what they wanted, but the customer can sometimes be fickle, and hard to please. We’d do well to look in the mirror sometimes, when we’re pointing a finger at the manufacturer!

Outstanding information that was surprising just as you stated. I did not know that about the pinned barrel !! Fascinating!

I think the internet might melt over that one! Ha!

I took a trip to pick up a revolver this week and they had a Smith in the case, it was mid sized and I didn’t take note of the model.

The one thing I can say is the trigger just isn’t “there” like my old 66. I would have liked to ask if that i s a design change, or just mine has years of use ?

I wouldn’t be surprised if a well-used revolver had a better trigger than a NIB gun. But S&W’s position is that if we took a dozen NIB guns from “back in the day,” and compared them to a dozen modern production guns, the newer guns would be better, on average.

Threre is a matter of QC, as we discussed in the comments to previous stories. It’s simultaneously possible that the new design could be better than the old, but the results still not as good, if S&W isn’t doing a good job with quality control. That’s an entirely different conversation we could have, and I’m not real qualified to weigh in, since I don’t have significant experience with the new guns. I’d be interested to hear what the readers would say about that.

I special ordered a new production 610 with my LGS the week that they were announced. Landed somewhere between disappointment and brokenhearted when my wheelgun showed up with an obviously overclocked barrel. I became irate when S&W returned it to me with a letter saying that it was found to be “within tolerances.” I haven’t purchased a “new” S&W since, and came upon this article doing research and preparation for a (well equipped) garage barrel swap to right what the machines boogered up.

Having said all that; the locks are easy to defeat and I own five two-piece barreled revolvers (one K frame and four X frames) from prior purchases and love each of them, but they’re nothing like my “limited use” No-Dash models. With Kimber casting their hat into the revolver business (can you say recessed charge holes?) and Colt rejoining the fray; S&W has a tremendous amount of work to do to regain lost market share. I do hope they pull it off, but I’m not going to hold my breath,

The QC element is the main issue. The root design can be good, but if the proper care and attention isn’t there during manufacturing and assembly, it doesn’t matter. I know folks inside S&W that are working hard to fix those problems, but it’s a work in progress.

Good luck with that 610. I hope you can get it clocked properly!

I think Mike’s first sentence hits the nail on the head. Comparing a revolver that has been worn in to one that is new is almost always going to favor the one that is worn in. It’s not really an apples to apples comparison. That said, I don’t know how you avoid the comparison unless you take all the worn in revolvers and hide them until the new ones are equally worn in, and that just seems silly when you could have fun shooting either or both.

Re: NIB vs. “worn-in” revolvers: Back in 19(mumble-mumble) when I was first sworn is as an agent, I was issued a pre-Model 10, 2-inch M&P that was older than I was. Its action was like glass; I don’t think I’ve ever fired a revolver with a smoother action. About the same time, agents from another agency were all issued brand-new Model 66s and they were told to dry-fire them every night to smooth up the action. So the idea that a properly worn action is a smooth action has merit.

On the other hand, I’ve been told that the triggers on the new K-frames are just not as good as the ones on the old ones due to the redesign of the actions from hammer block to transfer bar. My experience with the new K-frames is exactly zero, so I can’t judge the truth of that statement.

A friend bought a pair of the new Model 66s, one with the 4.25 barrel, another with the 2.75” barrel. The longer gun had a “pretty good” action from the start (he rated it as “better than some of the older ones”), which has improved with dry fire. The other one had a “horrible” action that has only improved to “passable” with “about a thousand” dry fires.

He posits that the older guns smoothed out more quickly with dry fire, because the parts were softer and “broke in” faster. In contrast, the much harder MIM parts might need a longer break in period before they smooth out and you sense an improvement.

Seems like a reasonable theory to me. If you get a set of good MIM parts from the start, you’ll probably have a pretty good pull, on par with the older guns, but a bad set may take much longer to smooth out.

Yes, your theory about harder MIM parts breaking in more slowly than softer non-MIM makes more sense, I think, than the action redesign. After all, the change from hammer block to transfer bar theoretically doesn’t affect the trigger at all (maybe it does, I don’t know), and Colt and Ruger, which have used the transfer bar system forever, have decent triggers. Another myth busted!

I’ve owned several modern production Smiths and they’ve all been great guns with two caveats:

1. The cylinder release thumb piece screws have backed out on two of J frames, leading to the part falling off the gun while firing it.

2. Nearly every S&W revolver I’ve examined over the past year has had rubber stocks that are mismatched, giving the front strap an unattractive and uncomfortable ridge where the two halves meet. They are also rarely flush with the frame where they meet the top of the back strap. While not a huge deal, it doesn’t inspire a whole lot of confidence in overall QC, though that may be more the fault of Uncle Mike’s or whoever is manufacturing the stocks for S&W these days.

Granted these have all been J frames which I would venture to guess are the most mass-produced and built to a price point revolvers they manufacture. This hasn’t dissuaded me from carrying mine every day, reliability and accuracy have been excellent.

Andrew, thanks for sharing your experience with the new product. The Uncle Mikes copy of the Spegel Boot Grip that came on my early-90s M640 was a quality piece of gear, but I’m much less impressed with the current rubber stocks. They would be quickly replaced with something better if I was buying one of the new, no-lock J-frames.

It’s interesting that the thumb piece screw coming loose is a trend item. I’ve never had any issues with that on my older J-frames. I guess you’ll want to keep a screwdriver in your range bag and check frequently.

I’m super glad to hear they have been reliable and accurate for you!

Sir, your latest offering detailing the product improvement process at S&W is a fascinating read.

The only defective firearm I’ve had came out of Springfield. It happens and hasn’t deterred me from purchasing and carrying a couple more no-lock models.

I’d like to add that I, for one, appreciate the work you guys put into this site. Truly a labor of love.

I hope that there are far more readers than those who regularly comment on the excellent subject matter put out on RevolverGuy.

Thank you Bill! That’s most kind of you! It always warms my heart to hear how much you guys appreciate the blog. It’s fuel for my engines. I’m sure we’ve got many more readers than commenters, but we’d love to hear from more of the silent ones.

You’re right—ALL the manufacturers make lemons, from time to time. I’ve had bad guns from a bunch of popular makers, but they’ve been really good about making things right. I still think the customer service in the gun industry is superior to any other industry we deal with, as consumers.

Holy cow, a lot of interesting stuff to unpack here, but I agree with the Colonel that today’s Smith and Wesson revolvers are stronger and more consistently and efficiently manufactured than they were many years ago.

If it weren’t for the ungainly lock I probably would buy a new Smith. So, I’ll just have to suffer with my cache of old-school S&W wheel guns.

“Suffer” 😆

I’m with ya on the lock, brother.

Sir,

thank you again for a fascinating article! I must say I am a fan of better quality over aesthetics for life saving tools… If only they didn’t have the lock… sigh…

So I’m on guard duty thinking about an I frame I have from (I think) 1917- no roll stamp on either side. The thing is no longer blued, and the rifling is worn and pitted until those 98 grain .32 RNLs start to tumble around 20 feet downrange… fully keyholing before 30 feet. When I think about it, these unstable bullets might be more effective stoppers due to early upset… but I’m rambling.

Anyway, this thing has beautiful knurling on the head of the ejector rod like we never see these days. I can appreciate that kind of craftsmanship on the old ones which doesn’t show up on modern guns. But the cylinder lug. Oh the lug. Worn down enough that from time to time the cylinder slides past on opening. Score one for the new method.

It’s amazing to think how much effort and craftsmanship was involved to make those guns using the older methods, isn’t it? Alas, the new ones are much, much stronger, even if they lack the charm.

I think you’re onto something with those tumbling .32s!

Great article a informative essay, thanks Dave

I for one like the standardization on the round-butt frame. Back when I was carrying concealed revolvers for a living, I had two 4-inch revolvers, a Model 66 and a Security-Six, converted from square-butt to round-butt, both for concealability and for ease of shooting. Back in the 80s, the FBI Academy was sued by a group of female agent trainees. I don’t recall all the issues or merits of the case, but I do recall that one of the issues was that issuing square-butt K-frames to female agents who had smaller hands adversely affected their shooting scores. The contention (and I agree with it) was that the round-butt K-frame was optimal for all adult hand sizes.

Back in the 80s a custom shop (Lew Horton, maybe?) offered short-barreled N-frames in .45 ACP and .45 Colt. The grip frames were modified to round-butt K-frame dimensions. I wanted one badly, but the damn rugrats needed feeding. Now the rugrats have left the nest, but if I’d bought one of those N-frames I’d still have it.

There you have it. For the record, Old 1811 prefers round butts. 😁

All jokes aside, I agree that the RB grip frame probably fits the average hand better, and since we can “convert” a RB to SB with grip choice, it makes sense to standardize on the former.

I sense another installment of the “guns that got away.” Those Lew Horton guns were sure neat, and I wish I’d bought a bushel of them!

Sir, I am shocked at your double-entendre. Such lowbrow humor has no place in a serious discussion.

(Did that sound convincing? Because the truth is, I actually laughed out loud when I read it, and if it weren’t for double-entendres, I’d be unable to carry on most conversations. Keep up the good work.)

And I was going to mention the ease of converting a round butt to a square butt with the proper grips, but my post was already too long. Great minds, and all.

I learned a lot from the article, but now I’m mad at my fake pinned-barrel K-frames. Kind of a good thing they all fell out of the canoe.

Haha! Another tragic boating accident. Almost makes me want to take up scuba diving.

Glad you’re enjoying the articles. It’s always great to hear from you here in the comments, even though you’re easily offended. 😆

Thank you for the excellent article explaining a lot of the production advancements S&W has made, Mike. The changes do make for a stronger revolver that will last longer and still be affordable for the dedicated consumer. By dedicated consumer, I mean Revolver Guy. The average buyer will default to the M&P9 2.0 electric gun with the 629.00 retail price instead of spending the 979.00 fee S&W recommends for a Model 66. S&W corporate responds to the world we live in, I suppose.

You make a very good point about quality control, too. If the folks building them and inspecting them are not switched on, you can still end up with a flawed product that requires factory repair. S&W still builds several models with one-piece barrels that occasionally get out with a barrel that isn’t “TDC”, or one with an unacceptable barrel cylinder gap. That QC role is critical….

I examined a J frame 638 (that looked out of place amongst all the autos) in my LGS recently. It was priced at 499.00. I was heartened to find it well fit and well finished with a smooth trigger pull. The cylinder went in and out easily and virtually glided on the yoke- lock up when closed was solid and the b/c gap was right. Golf clap for the Big Blue folks who built and checked it- gives me hope! I went back yesterday thinking I might buy it- and it was gone. Someone else appreciated it too!

If you get the chance to visit with the engineers again, I would sure like to get their take on the old cut rifling verses the new ECM/EDM style. The new style is certainly more efficient to produce. A few “Old Guys” that I respect insinuate that the cut rifling generally produces higher velocities than ECM, but there are obviously a lot of variables in play. Not a rabbit hole worth getting stuck in, just curious!

Thanks Mike!

Kevin, that’s a welcome report on that 638 sample you inspected. I’m hoping most of the new guns come out looking like that one.

Interestingly, from the reports I get from various sources, it appears that we might stand a better chance of getting a good J-frame than a good K-frame, these days. I emphasize “might,” as it’s certainly not definitive, but it just seems like the new Ks generate more complaints than the new Js. I’m not sure why. Are the K-buyers more likely to be enthusiasts who pay attention to the details? Are the Js more likely to become “sock drawer guns” that don’t get fired much, so any flaws go unnoticed? Are J flaws masked by the general perception that J-frames are hard to shoot and inaccurate anyhow? Does S&W do a better job with the Js because they build more of them?

Again, I’ll emphasize this is just a general impression I get from the reports I’ve received, and since I don’t have much experience with any of the new S&Ws, I’m not in a good position to make any definitive statements or pass any kind of judgement.

I’d be interested to hear more from our readers about their experiences, though. How are the new guns from a quality and reliability perspective? Do you sense any difference in the general level of quality between the J and K (or L, N, X) frames?

Well I’ll be darned……I guess I can’t be so smug about my 4″ HB Model 10…..I was so proud of the barrel pin…. 🙂

I love this site….for many reasons, but mainly for information just like that, thank you!

Mike, it’s all just part of my diabolical scheme to drive the prices down on pinned and recessed guns, so I can buy them cheaper. Shhhhh….don’t tell anybody.

The very first unpinned S&W I bought, a 629-1 8 3/8″ Had a barrel that would twist in the frame… I sent it back twice begging them to pin it. S&W refused. The third time I had it repaired…The barrel continued to twist. after the third repair it went done the road. I have never had it occur again, in the hundreds of S&Ws I have owned since.

I am struck by the irony the Dan Wesson’s brilliant idea was panned in 1968, but S&W managed to figure out some of the many benefits of a two piece barrel, by 1995…

S&W really stepped on it, when they were at all time low inventory, they didn’t delete the time consuming and costly lock. I’ve owned and shot hundreds of them. I still do and always will. I do chase after the prewar guns as they are smoother with the long action. I do own modern S&Ws, but do a lock delete.

How frustrating that must have been, Rob! Makes me wonder if the frame threads were out of spec. That’s a gun you certainly didn’t need hanging around.

It’s kinda funny how companies get so set in their ways, that they refuse to consider changes, especially if they come from outside. It only took what, a couple decades, before Ruger changed the bolt lock on their 10/22 so it would release with a tug on the bolt, like the successful aftermarket parts? Corporate inertia. Colt is still using components of a lockwork that was superseded last century . . .

Sing it about the lock, brother! It boggles me. They lose so much revenue over that abomination.

Mike,

You have done an unbelievable job on this series. The 25 year evolution from S&W left a lot of folks scratching their heads.

First off, Dean Caputo makes a very accurate observation. I can not recall ever seeing a pinned-and-recessed S&W revolver with a battered extractor. The cylinder is stronger and given it will generally meet the frame at equal points ( 12 and 6 o’clock ), there’s a lot of mass in that cylinder that isn’t going anywhere. Interestingly, Colt started with the Mk III series having variant on the S&W but using a totally recessed cylinder face. It emulated the S&W recessed chambers, but covered the entire rear part of the cylinder. It left an outer ring that contacted the locking bolt long enough to allow the cylinder and extractor to slide into battery. Good luck shooting one of those out of time ( I tried ).

Speaking of extractors, the square cut star and D shaped center shaft were a Godsend. I still have a small box of spare extractor index pins, because I’ve had to replace too many of them on older K frames. I went so far as to replace the cylinder on my M67-2 to have the new square cut extractor.

The barrel swap on S&W was always a hit and miss. In the 90s when there was a great dump of police trade in stainless guns, particularly 4″ M64 and 65s, I was keeping busy on the side with procuring 3 inch barrels from S&W, round butting the frame, replacing springs to bring things up to new spec, and either satin blasting or bright polishing them. Installing the barrels could be a real Bee & Itch on the stainless guns – getting the torque just right, and in some cases, having to use a lathe to cut just enough back for the barrel to torque to TDC.

You mention the Dan Wesson two piece barrel design. When it came out it was rather ugly, but folks soon learned that it was a custom adjustable tack driver. The asthetics pretty much killed it as it was way ahead of its time. Ruger later adopted the peg grip in the GP100, SP101 and Super Redhawks. Now S&W and Ruger use the two piece barrel system. What went around came around.

Polishing the action was done gingerly, thanks to the internal parts being so relatively soft under the surface hardening, so you managed to get the rough areas smoothed out without cutting through the case hardening. Some of us old pharts are used to guns from the 70s and 80s with more rounds through them than we can remember, and actions silk smooth. As for the new ones, I have as my bad-breath-distance backup a Model 37-2, DAO, factory bobbed hammer, without the lock, made in 2006 as part of a gubm’t contract that ended up being cancelled. When I got it NIB, the action was rough. Popping the side plate revealed a bone dry lock work of all MIM parts. A tad bit of Lubriplate on the contact surfaces, and this thing has a fantastic double action with a near perfect staging trigger. Chances are those ‘rough actions’ just need a bit of TLC to grease the skids.

The finishes on current guns may not be up to snuff, but S&W can still put a deep polished blue on revolvers – as Col. Mike can attest with the Twins (pair of M15 Combat Masterpiece sent back for restoration)

Why S&W took so long to relocate the firing pin in the frame still puzzles me. Colt did it early in the 1950s with the Python and 357 version of the Trooper, and then later with all the Mk III, V, and AA frame guns. Ruger did the same from the get go on all their cylinder based guns.

Subtle thinks like changing the front point of lockup seems to make for a more steady cylinder rotation and stability in recoil. It’s not as bank vault tight as the Ruger system, but it sure beats having it at the tip of the ejector rod.

Do I hold on to my ‘old model’ S&W guns? Absolutely. I love ’em and they’re a joy to shoot. Would I buy a new M66 ? If it didn’t have the Hillary Hole, yes !!

All in all, Smith & Wesson has pioneered technology and innovation on many fronts. From working the bugs out of the 9m/m pistols in three generations, to bringing the double action revolver into a new realm of precision manufacturing.

Thanks for weighing in with your considerable experience, Sir! I appreciate all the extra detail you provided, courtesy of your working history with these guns. I hadn’t thought about the Ruger grip peg being a copy of the DW design, but once you pointed it out, it made sense. The DW guns were certainly ahead of their time in many ways.

The Lubriplate comment was interesting. Maybe all some of these guns need is a bit of grease in the right place? You’d think that would be an easy thing to incorporate into the assembly process. Sounds like a big payoff for a small investment, definitely worth S&W’s time.

I’m with you about the lock. I’d have a considerable number of these new guns if it weren’t for that. One can always hope.

In practice, an outer shroud that looks like the “barrel,” with front sight integrated, is attached to the frame first, using a “key” on the rear face, that mates into a matching recess in the frame. The key ensures the shroud is properly timed, and the front sight is TDC.

Not always. It’s a long story, but I bought a new 66-8 that was not properly timed. In timing it (on the first return), the warranty repair guys apparently turned both the shroud and the barrel in, reducing the barrel-cylinder gap to the point that the gun would not run once it was warmed up. After the second return for that issue, they replaced the gun (the replacement needed its own return for a problem).

Admittedly, that’s a sample of two guns, but I’m not sold on the “the new guns are better” argument.

Thanks for the data point, Misfit. Nothing is absolute, of course, but the new system does promote better barrel timing, on the whole. Sounds like you got one that was the exception to the rule, which always happens to somebody.

How frustrating that the replacement had its own set of warts! Once again, we return to that QC question. The engineers can build a better widget, but if the manufacturing and inspection/QC process doesn’t perform as expected, the final product will disappoint. I’d sure be interested to know how the warranty return numbers on the new guns compare to those of old. Things were pretty bad in the Bangor Punta and Lear Siegler years at S&W (which some folks now romantically remember as the “good old days”) with a high number of product returns. It would be good to know if the new CNC/MIM guns have generally improved things, in that regard.

I love and treasure the older S&W guns, but times change. And S&W have been making some really interesting guns that can’t be duplicated by “going old”. The M69 44 Mag, 8 shot 357 N-frames, 340PD and extra-light kin in J/K/L/N frames, higher capacity 22 caliber J-frames, 327 Federal Mag guns, all interesting and unique items.

The lock is a BIG issue, a negative brand image with a sullied reputation. If it’s so important to have a storage lock on the gun, use the Taurus system. Much more elegant.

But, I keep breaking down and buying the cool new guns. I’ve bought roughly a new S&W wheel gun a year for the last 6-7 years. The rub is in the quality of assembly. S&W is great when you call them with a problem, but half the guns I’ve bought have taken a trip back to the factory. A Performance Center N-frame that skipped chambers (ie lack of ignition), an L-frame that spit lead out the cylinder gap, a j-frame that would lock up after part of a cylinder was fired and one other I can’t recall right now. These problems all arose pretty early in my usage. But a 50% problem rate on brand new guns is pretty unacceptable.

I’ve also seen the cylinder latch button screw go loose on the J-frames (two in my case) as mentioned above (but that is easily fixed with a touch of blue thread locker).

I do carry one of the newer lightweight (no lock) J-frames every day, as the weight savings is well worth it. But I put 500 rounds through it first.

Hmmm. A 50% return rate is troubling. It sounds like the problems were corrected to your satisfaction, but you shouldn’t have had to spend that much on postage. It’s a good thing you stress-tested that J-frame before you relied on it.

Upon further thought to my first comment, I think all the recent S&W wheel guns to go back for warranty work were “higher than historically normal” capacity and all the ones without issues were “historically normal” capacity guns. Might be something there.

I’ve heard the 8 shot 22 LR J-frame (43c) might just be a little over capacity for its size, and thus tends to have issues with the lock work. I want one, but I’m a little hesitant based on reports.

There’s just something inherently wrong with a seven shot (or eight shot) six shooter.

I can’t avoid having a “Spinal Tap” flashback:

“These go to eleven.” 😆

Interesting you say that, as I’ve always wanted one of the 6-shot Model 617s, but could only find the newer, 10-shot guns. I’ve always wondered if the changes required to make these “high capacity” cylinders work influenced the quality of the actions? Perhaps that would be a good project to work on, sometime.

Thank you for this most informative and balanced series of articles. Well done, sirs. Just a few ideas:

1. The lock continues to be the main reason I haven’t bought any post-1990s S&W revolvers. I really think they dont appreciate how many sales they are losing because of that. Not only does it represent the dark days of the gun lawsuits, its ugly by itself and also ruins the lines of the j/k/ l models by adding that ugly hump. I wish someone could help them realize that.

2. Can they work on the finish? The new Combat Magnums look like they have been spray painted out of a can.

3. To make their revolvers like in the old days, I know, would likely mean prices of 2000+$. But the high end 1911s (Wilson, Brown, Nighthawk) and SA revolvers (Freedom Arms) sell for more than that and they seem to sell quite well. I think a US company is missing a bet by not marketing a finely crafted high end DA revolver. (The Korths look very nice but being German parts and services are limited.)

Thanks again,

Paul B.

Thank you Paul! I’m in agreement with you on all points. Colt has recently shown us, with the Python, how you can still achieve a beautiful polish at prices the market is willing to bear. It wouldn’t make sense to build all, even most, of the guns with that level of finish (because the average consumer wouldn’t want to pay the premium, which is why the New Cobra and New King Cobra finishes are less refined), but perhaps a few Performance Center offerings would be appropriate?

On that note, the original charter of the Performance Center was very different than what we see today. It was a true custom shop back in the days when Paul Liebenberg ran the show. I’d like to see a return to that. A revitalized Performance Center could build Nighthawk-level quality revolvers that would make you forget all about the Korths.

Thanks for the great work you guys are doing here.

My experience with the new guns has been really good. After buying several over the last 20 or so years,I’ve had only one that needed to go back to be fixed. That was my 317 kit gun. It had timing issues. S&W took care of it at zero cost to me and it works great now. My most recent S&W purchase is my Model 19 carry comp that I got 2 years ago. It has been wonderful. A great fighting revolver that I would put up against anything.

I too wish the lock was gone but I’m glad I’ve not let it cause me to miss out on so many of my favorite guns.

The TK Customs lock delete kit is an easy fix if you want your lock out of there. I’ve done it to one of mine. Thanks

Thanks Billy, I really appreciate your feedback. It’s an excellent data point, and I’m glad to hear you’ve had such good experiences with the new guns. The TK Custom lock delete kit is a great piece of gear, for those who want to go that route. We’ll be doing a feature on that sometime in the next year.

I appreciate what S&W has done to improve its

line of revolvers. But when all is said and done

when it comes to thinking of a new manufactured

revolver, I look to Ruger and Colt.

For years I’ve shot and collected S&W revolvers.

But perhaps wrongly, I see more acceptance of

the Ruger and Colt revolvers in postings among

gun forum members.

In S&W’s case, it seems more guns are put on the

market with misaligned barrels, poorer triggers

than its competitors.

Ed, I don’t think you’re alone. Ruger sales really took a jump when they started offering guns like the LCR as alternatives to the S&W Js, and invested more effort in refining the GP and SP series guns. Of course, the rebirth of Colt’s revolver lineup has been fun to watch, and they’re making very good guns. The GA-based Taurus is coming on strong, and Kimber has captured some hearts, too. There’s lots of good alternatives to the S&W guns these days, which is why I’m even more surprised that they’ve made some of the choices they have (like keeping the lock, even though it suppresses sales, and failing to broaden the catalog).

My three revolvers are all S&W:

1981 Model 10 HB 4″

2010 642 2 1/2″ w/ a black pinned front sight, full length shrouded ejector rod and that dreaded lock.

2020 686+ 3″ and the ugly lock.

I located a 3″ .357 five shot, with factory front night sight, VZ grips and NO lock for $424.

I wish it was made in America by S&W, Ruger or Colt. Alas, it’s made in Brazil and thus I’ve held off on purchasing my 4th revolver.

One out of three ain’t bad, Opa!

I get what you’re saying Opa, but if you’re ever able to get past the Brazilian angle, as I have, you may find yourself pleasantly surprised. Along with my Rugers and S&Ws, I am the semi-proud owner of an 856 UltraLite snub (.38+P), a 605 snub (.357 Magnum) and an 856 TALO Edition 3″ (.38+P). Unlike their American-made cousins (a Smith and a Ruger that were defective), none of them have had to visit the hospital in Bainbridge, GA for rehabilitation and are the best shooters I’ve got.

All this lock talk (which I avoided in my initial post) has me wanting to add this little anecdote:

After having a literal blast (pop?) at the range with my newly-acquired Barkeep, yesterday, I thought, “Why not go across the street and see what my LGS has in .22LR for me to carry around?” There, displayed on the rack was a Model 317 (muzzle facing to starboard). After a bit of schmoozing, my guy took it from behind the glass, handed it to me, and while marveling at its lightness, I let out an audible groan. “Can’t get past that lock, huh?” Needless to say, I left empty handed.

Bill, they certainly MUST know by now, how the lock is suppressing sales!

Said Capt. John Smith when notified that his ship had struck an iceberg . . .

Truly, I don’t know what the S&W leadership thinks of the complaints noted above in regard to their current revolver lineup, or if they even care. But Smith is not alone–other firearms companies have had, and some still do, problems with their designs, quality control, and lowered sales.

Ultimately it’s up to customers to either keeping purchasing crummy stuff and therefore enabling more of the same, or to buy elsewhere and hopefully force the company in question to improve its products.

Remember, no one has an obligation to purchase subpar items.

Spencer, I’m under no illusion that anyone at S&W corporate is reading RevolverGuy.

Nor am I. In my other life, I write for a publication in the old-car hobby. Modern manufacturers (cars or gun) cater to the highest-possible profit margin. I can’t blame them, but they forget their heritage and niche markets that can turn a profit.

For cars, it mystifies me that sports sedans and two-seaters (other than the Corvette) cannot make a profit in volume by the Big Three. Thus I bought and restored a nearly-vintage Miata, 5-speed and all. What a joy to drive it is.

For guns, it mystifies me that quality revolvers cannot turn a profit and be part of a “heritage” series that would lure some younger plastic-fantastic users. My CZ is considered “old school” at the range, but the serious RSOs and counter commandos love them. And some youngsters who see my GP100 or S&W 64-3 admit they want to add a revolver soon to their collections.

S&W needs to market to that market, too. Ruger has sold a lot of Wranglers…

I remember what Mama said long, long ago, if you don’t have anything good to say, don’t say anything at all.

I will say that I very much appreciate the articles you have done on this subject. Had to take a tremendous amount of research and all put together in your good style.

I think the thing that strikes me so hard is there seems to be no craftsmanship or pride in the products anymore.

I long for the good old days gone by, in so many ways.

Indeed, Tony. I miss them too.

I’m sure the individual workers at S&W are proud of their work, but there seems to be little sense of the heritage and import of these guns at the corporate level. Or, if there is, it’s somehow not being communicated effectively to the consumer. I’d enjoy getting an hour to chat with the CEO about that, and what I’d do to correct it.

Outstanding article Mike! You have gone above and beyond with this series of articles. I have been an S&W Revolver fan my whole life and although I have tried some other brands, I always felt better carrying a Smith in my hip. While I do love the vintage models, I bought a new 66-8. While working on my own review of it, the sickness grabbed a hold of me and I picked up a new Carry Comp Model 19. Now, I am trying to put both through the paces, hoping to bring you good news for both. So far, the 66-8 with 2.75in barrel has not given me any reason to complain. The carry comp 19 had 1 hiccup. The first 6 rounds out of the box were Remington 357mg 158gr semi-jacketed hollow points. The cylinder would not open… I beat it open with my palm, and extracted the empties.. took it home, took off the side plate. Everything looked fine and clean but I sprayed it out, lubricated it, and have not had the problem repeat. I am at 200rnds now with 3 different brands of magnum ammo and it is doing fine. I hope it was a fluke and I wont have any more issues with it.

Mark, that’s a strange one with the Carry Comp, but I’m glad it worked itself out. Maybe there was a burr somewhere that you knocked off? Maybe some primer flow from a bad primer? So many possibilities, but I’m glad it’s working well now. Also glad to get a good health check on the new Model 66. I’m glad you enjoyed the series and look forward to hearing more about your progress with that pair!

Hey Mike, Just to reply to your post: For all my warranty issues, S&W has always issued a shipping call tag for me to send my gun into them for service at no cost to me. And they will ship it back at their cost. Plus it doesn’t take very long either. I can in no way fault the warranty service process in terms of cost (none) or speed (fairly quickly).

In fact, a 66-8 2.75″ just followed me home the other day, I’m not checking an old S&W on a commercial air plane to Revolver Round Up.

Can’t blame you there, one bit. Be sure to give us a progress report on the new 66 please!

Great article. However, improvements or not, I’ve not purchased a single S&W revolver with the “de-provement” of the Hillary-hole lock.

I’m glad there are no-lock models available now and again, but to me, it’s the single greatest barrier to purchase.

Own several pre-lock S&W revolvers. I’d consider a new no-lock model. I would like to buy a new S&W revolver, but am precluded from doing so by the infernal lock on the models in which I’m interested.

I won’t pay a dime for one with the lock. If a lock model were gifted/given to me, I’d sell it to guy something else. I won’t own one.

I don’t know a single person who “likes” it, or uses it. No idea who S&W thinks their appealing to or why it remains (Prob. because of the involvement of Safe-T-Hammer.)

I applaud S&W for moving their headquarters to TN. It was overdue. However, I don’t have much optimism that the Hillary hole is going away as long as Safe-T-Hammer is involved.

Ariel, you’re certainly not alone. Even at this late date, the lock is suppressing a lot of sales. I can think of a dozen guns I may have purchased, were it not for the lock.

I’m a “new age” revolver guy, I’ve never owned or even fired an old revolver at all and only own new S&Ws. I couldn’t be happier, I don’t like the lock however I’ve never experienced a problem with them either, the MIM, 2 piece barrels etc don’t bother me, and my EDC is a 4″ 686+ that has a few thousand rounds of Remington UMC 125gr SJHP 357mag, my carry and range ammo. The 686 is accurate, tight and just beautiful! I’m in love with my new Model 19 and it’s become my safe queen, I have a new Model 27 that had QC issues but S&W made good on it and that too is a safe queen buried at the bottom of the safe for extra special safe keeping, lol! I have a 627 Pro that gets alot of range time along with the 686+…I’ve never fired anything but full house 357mag through all of them, Remington, Federal, Underwood, Buffalo Bore, Double Tap etc. So maybe I missed something but I’m 100% satisfied! I’m happy with Smith and Wesson and really thank their engineers for the quality products they’ve helped put out.

I always look forward to the next Revolver Guy article and I really love and appreciate the work y’all do and the time it takes to put our these posts or “articles”! Thank You !

Thanks for the glowing report, Bob! That’s a very useful and appreciated data point! Thanks also for the kind words—I’m glad you’re enjoying the blog so much. Much appreciated.

At age 81, I don’t shoot as much as I used to, and have never owned a Smith with a lock. Nowadays, my 442-1, is all I carry. A speed strip with 5 rounds is also unobtrusive. My whole life I’ve been a revolver guy, and I appreciate well-written articles, free from commercial pressures. Thanks for what you do, and please keep it up.

Thank you Sir! We’ll keep writing if you’ll keep reading!

Thank you for the excellent detailed work here.

I’m fine with modern S&W designs. Not crazy about J-Frame triggers, and I don’t want a light-weight gun. Luckily the Kimber K6S scratched that itch for me.

The lock? I don’t worry much about it in a .38. I might on a 629, but I don’t carry a .44 mag and the one in our family has never failed. It’s a fun shooter for the outdoor range.

A feature of the Kimber I love are its recessed chambers. It may be the difference in design from what S&W did, with Grant Cunningham’s input, but it does not trap debris in my experience. It makes reloading a little faster, not that I expect to reload in a crisis, even with my CZ-75. But never say never and train accordingly.

Beveled, recessed chambers would be even better.

I’m 55 years old and I’ve been shooting since 1980 (I was 12 yoa). I started out shooting my dad’s Idaho State Police S&W Model 65 (which he purchased when ISP went semi-auto in 1991 and I inherited in 2016) loaded with 38 special full wadcutters and his Model 36 back-up piece – also loaded with 38 wadcutters. I have that one as well. Both of those revolvers are great shooters, and both were made during the despised Bangor Punta Era at S&W! There was a time that many hated the revolvers from that time period and now they’re desirable collector pieces. Funny how that seems to happen.

I own all of the Gun Digests from the fifties and sixties. Not surprisingly there are articles descrying the decline in American manufacturing and the quality control standards of American gun makers. According to some of the writers from that era there hadn’t been a decent firearm made since the thirties. Some even took it back to the nineteenth century.

I’m not doubting the posters here and their issues with their revolvers. It definitely happens. Col. Askins documents problems with the sights/barrels of the New Services that were shipped to the U.S. Border Patrol in the 1930s directly from the Colt factory. He corrected some of the guns while others were sent back to Hartford. This was during the supposed Golden Age of American revolvers.

Just saying there are always going to be issues and the American gun-owner can be a contentious individual.

Jeff, that’s a wonderful perspective!! So true! Thanks for sharing that.

Yes yes, lots of improvements. Heres one they need to do: REMOVE THE INTERNAL LOCK!!

No argument, brother.

Boy, was that a great informative article. I’ve been away for years as other interests got my attention but I’m back now. Its rare to find reliable information that’s not off base. Grant Cunningham pointed me here. You can thank him.

Thank you Sir! Glad you found it useful, and welcome back to the community!

I’ll definitely pass along my thanks to Grant. It’s quite an honor to have him recommending our work!

Thank you for the article. As I’ve probably said before, I am a fan of S&W revolvers. While I do not like the internal lock, it is not a deal breaker. My 642 has never given me any problems.

The only post lock Smith I own is a 625-8 PC. I had to deburr the chamber mouths and the firing pin is too short so I put in a longer strain screw as a temp fix until I get an Apex firing and I took the lock out. It’s accurate and I like the gold bead front sight. Honestly I’ve shot my 1917 Brazilians a lot more and carried them more too. It would appear all gun makers are using the customer in place of the QC dept. As to the grip situation people threw away grips that were uncomfortable to shoot. The “coke” N frame grips are like custom made. The pre-war Magnas are comfortable. When they started shaping grips shaped like 2×4’s people took them off. S&W seem to have no grasp of the human hand.

Excellent and insightful article. I found it shed light on quite a few areas I had previously wondered about!

I am hoping that, by tapping into this group of serious revolver-heads, somebody may be able to tell me why my new 686 has a series of blind holes drilled in both sides of the grip frame. There are 6 on the left side and 7 on the right side. Not symmetrically arranged on both sides of the front and rear straps.

Kiwi, this was a brand new, straight from the factory gun?

Yes

Hmmm. Not sure about that. Perhaps to index the frame during machining operations? A way to trim some weight from the frame? I’ll have to ask around. Since I don’t own any of the new guns, I’m not familiar with that feature.

Hi Mike. From my postings on various forums there is no certain answer but the most common conjecture is CNC reference points. I find this odd as it seems to be a very rare thing. Apparently S&W are not answering questions people have sent them on this. It would be nice to know for sure but maybe I will just put it down to something else I will forever be ignorant of! Then again, as one responder suggested, it could be aliens!

Hmmm….aliens working at S&W could explain a lot.

I love Smith and Wesson guns and own way too many. I bought a pair of 624 when they were available without the lock and a pair of 340PD without the lock. All of the other Smith and Wessons I have bought over the last several years, have been older much more expensive ones without the lock. Finally found a 3″ CS1 recently but was just about to buy the Colt 3″ Python. There are at least a dozen new Smith and Wesson revolvers I would like to buy that do not have an older brother like a 329 etc. If I can’t find a used one, or unless they continue to make a few revolvers without the lock, otherwise I am going to be a Colt guy I guess. I have shot the 4″ Python and it is a wonderful gun except for that scratching computer stuff on the frame in front of the cylinder. Spent my career in marketing for a manufacturing company and am well aware of the lawyers and accountants screwing up great products but hate to imagine how many potential customers have swithched to plastic guns. Wonder how much of the switch to automatics is related to this perception of poor quality from Smith and Wesson. With Colt coming back and the new manufacturers starting to make revolvers I hope Smith and Wesson is listening to the market.

Thank you for this article which is clearly a well researched work.