America is a patchwork quilt of gun laws and public attitudes towards guns. Even though we’re all Americans, the gun culture can look very different from state to state, and region to region.

Yet, while gun rights and the gun culture are under serious attack in some locales, with significant restrictions placed on the ownership and use of firearms, Americans are generally very fortunate to enjoy some of the best access to firearms and ammunition in the world. There aren’t many countries where law-abiding citizens have access to such a wealth of firearms and related products, and the ability (and means) to lawfully possess privately-owned arms and ammunition.

I was reminded of this recently by a series of fascinating email conversations with a RevolverGuy reader from the country of Brazil. RevolverGuy “Erick” is a dyed-in-the-wool “gun guy,” who also happens to be a police officer in one of the most violent nations of the world. As a result, his perspective is exceptionally valuable in helping us to understand the nature of the gun culture in Brazil.

Since we rarely get a glimpse into the details of foreign gun cultures, I thought it would be particularly interesting for RevolverGuy readers to learn more about Erick’s country, the firearms one is likely to encounter there, and the nature of private gun ownership and use. So, get ready to plunge right in with Erick’s help, and keep your eyes peeled for some neat revolver-centric information from the largest country in South America and Latin America.

A brief tour

At 8.5 million square kilometers (3.2 million square miles), Brazil’s landmass covers more than 47% of the continent, and makes it the fifth largest country in the world, by area. Brazil’s 213+ million people also make it the sixth most populous nation in the world (by contrast, the United States has about 332 million, making it the third most populous nation).

Sadly, Brazil’s homicide rate also consistently ranks amongst the highest in the world. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime estimates that in 2017, there were an estimated 30.8 intentional homicides per 100,000 people (64,078 homicides, total) in Brazil, making it #7 on the list of countries with the highest murder rate, behind El Salvador (82.84 per 100K), Jamaica (57 per 100K), Honduras (41.7 per 100K), Belize (37.9 per 100K), South Africa (35.9 per 100K), and Lesotho (41.25 per 100K). In comparison, the United States’ homicide rate is about 5.35 per 100,000, and Canada’s is about 1.68 per 100,000 people.

Brazil was a colony of Portugal until it gained its independence in 1822, and became an empire ruled by a constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary system. A constitution was ratified in 1824, and a bicameral legislature was soon added. In 1889, a military coup displaced the monarchy, and 5 years later, they transferred control to civilian leaders, leaving Brazil’s government to become a presidential republic. Economic, social and political instabilities in the 1920s paved the way for another military coup in 1930, which left military dictator Getúlio Vargas in power for 15 years.

Following World War II, a military coup deposed Vargas and allowed a series of civilian governments to rule until 1964, when yet another military coup resulted in an authoritarian military dictatorship that ruled until 1985. Civilians regained control of the government in 1985, and a new constitution was ratified in 1988 to replace the highly restrictive one that had been imposed by military dictators in 1967. The 1988 constitution established Brazil as a democratic federal republic, and a series of civilian presidents have served the country ever since.

The president that was elected in 2010 brought Brazil to the political left, and supported a number of foreign communist leaders. This president was eventually impeached as part of a widespread corruption scandal that included bribery and tax evasion, and a right-wing, reformist president, President Jair Bolsonaro, was elected in 2018. President Bolsonaro survived an assassination attempt during the campaign, and recovered from the vicious stabbing attack in time to assume the presidency in 2019, where he continues to serve today.

Brazilian Firearms Laws

The firearms laws in Brazil are much more restrictive than they are in the United States, and strongly reflect the turbulent political history of Brazil in the 20th Century.

During the military dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas, from 1930 to 1945, Vargas implemented strict controls on the civilian possession of firearms and ammunition. As the target of three armed revolutionary attempts to remove him from power, Vargas was not supportive of an armed population, and sought to restrict civilians from owning arms that would be of military use.

Under the rules imposed by Vargas, civilians could not possess centerfire rifles capable of shooting cartridges that delivered more than 1,200 foot-pounds of energy, which limited rifle shooters to moderate power handgun cartridges only. Shotguns up to 12 Gauge were permitted, but all 12 Gauge shotguns were required to have a minimum barrel length of 24 inches, to make them more suitable for sporting use, than for military or defensive roles.

Under Vargas, handguns were restricted to “non-military” calibers—no greater than .32 ACP in autopistols or .38 S&W in revolvers. An energy limit was declared for .38 caliber revolvers, to restrict the power of cartridges fired in these guns—a maximum of 25 kgm (about 180 foot-pounds). Under these restrictions, handgun calibers like .380 ACP, .38 Special, .30 Luger, 9mm, .357 Magnum, or .45 ACP were prohibited for civilian use. Such calibers were restricted for military and police use, only.

Mandatory gun registration and licensing schemes were installed, and mandatory fees were imposed for both, to discourage ownership. A maximum cap of six firearms (two handguns, two shotguns, two pistol-caliber rifles) per qualifying citizen was instituted. Carry licenses were not federally restricted under Vargas, but individual states were allowed to impose restrictions on citizens, and withhold permits for discretionary reasons—and many did.

Civilians were also limited to purchasing 50 cartridges per year for their permitted firearms.

These laws remained on the books in Brazil through the back and forth transition between civilian administrations and military dictatorships that replaced them. Interestingly, the military dictatorship that ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985 (the “Fifth Brazilian Republic”) did improve one aspect of Brazilian gun laws, when they approved the .38 Special for civilian use in 1965, as part of a review of gun classifications. The Vargas-era energy limit of 25 kgm for .38 caliber revolvers was eliminated, but “Magnum”-designated handgun cartridges of any caliber were still restricted—even the .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire!

In December of 1987, the Minister of the Army (equivalent to the Secretary of Defense, in the United States) changed the caliber restrictions to permit civilians to own .380 ACP autopistols. Revolvers were still limited to the .38 Special.

In 1997, the Brazilian president signed a law which required psychological testing and shooting competency tests as conditions of issuing a carry permit. This complicated the process and reduced the number of permit applicants.

In 2003, the responsibility for issuing carry permits was transferred from the states to the federal government. Because the Federal Police infrastructure was smaller than that of the collected state police forces, and they had less personnel dedicated to issuing permits, this made it even more difficult to obtain a carry permit–particularly in smaller cities that lacked a Federal Police office. As before, when the states issued the permits, the Federal Police could refuse to issue a permit for discretionary reasons, and often did.

In October of 2005, the citizens of Brazil were asked to vote on a referendum that would decide the fate of civilian ownership of firearms and ammunition in Brazil. Article 35 of the Disarmament Statute would have prohibited the sale of firearms and ammunition to citizens, if approved, and it was strongly supported by the federal government, the media, the Catholic Church, and many foreign gun control organizations. Despite this, the article was rejected by 64% of the Brazilian voters in the referendum, and they retained their right to purchase arms and ammunition.

However, the federal government in Brazil continued to push for additional gun restrictions and prohibitions, ostensibly to deal with the violent crime that plagued the nation. These pressures intensified under left-wing administrations.

Changing tides

The 2018 election of President Jair Bolsonaro changed the landscape of Brazilian gun laws, however. President Bolsonaro campaigned as a pro-gun candidate, and delivered on his promises after taking office. He believes the solution to reducing the criminal violence that plagues Brazil is to support aggressive law enforcement operations, and to arm responsible citizens so they can protect themselves from the criminals, who are armed with illegal weapons.

As such President Bolsonaro signed an executive order in January of 2019 that relaxed some of Brazil’s traditional disarmament restrictions. The order eliminated handgun caliber restrictions for civilians, and made it easier for them to own and store firearms in their homes by increasing licensing periods from five to ten years, and increasing the number of firearms that could be lawfully owned. Safe storage requirements were also specified as part of the order.

Another executive order, signed by President Bolsonaro in May of 2019, allowed rural gun owners to use their firearms on their own property (instead of restricting use to a licensed gun range), eased firearm transport restrictions between home and the range, eased import restrictions on firearms and ammunition, and increased the ammunition purchase cap to 5,000 rounds per year (instead of 50) for civilians.

Additionally, President Bolsonaro signed four new decrees, in February 2021, which increased the number of firearms that could be owned from four to six (up to 60 for some active sport shooters), and increased the number of firearms that could be carried in public to two. The decrees raised ammunition purchase caps to 2,000 rounds per year for specially regulated weapons, and relaxed restrictions on optics, pre-20th Century firearms, and ammunition up to 12.7mm as well. Most importantly, the licensing requirements for hunters, collectors and sport shooters were eased, to permit greater access to firearms.

President Bolsonaro also reformed Brazil’s carry permit regulations, turning the discretionary, “May Issue” system into a “Shall Issue” process. Additionally, he authorized military members with ten years of good-conduct service to obtain a carry permit.

Obtaining firearms and ammunition in Brazil

Gun stores in Brazil are privately-owned, not run by the state, as they are in other Latin American countries. Erick reports that many of these businesses–including some which had been in operation over a hundred years–were regrettably closed during Brazil’s left-wing, anti-gun presidencies. However, new businesses have opened to serve a public that is increasingly hungry for arms and ammunition, in light of President Bolsonaro’s reform of Brazilian gun laws.

Our RevolverGuy friend Erick indicates that citizens must pass a background check, psychological screening, and practical firing tests to obtain a firearms license in Brazil. Select police officers are trained and certified to administer these practical tests. Erick advises that obtaining a permit to carry a firearm outside of the home is both difficult and expensive (about U.S. $200), but is no longer impossible after the latest reforms. Still, there are few people, outside of police officers and qualified military members, who can lawfully carry firearms outside the home in Brazil.

Although President Bolsonaro has relaxed import restrictions on foreign firearms and ammunition, these products are still difficult to obtain, and generally very expensive in Brazil. An unfavorable currency exchange rate drives up prices on foreign products, and fluctuations in the exchange rate often interrupt the supply chain, creating shortages that inflate prices. The most affluent Brazilians chase the limited supply of foreign arms and ammo, but most Brazilians target domestic products for their affordability and availability.

Taurus and Imbel are the two most prominent firearms manufacturers in Brazil. The Taurus products are well known to Americans, since they have been imported here since 1968, and imported, manufactured, and distributed by an American division of the company since 1982. The Imbel name is less familiar, but Americans actually know many of the Imbel products, because they have been imported here under the Springfield Armory label. In example, Imbel supplies 1911-style pistols to Springfield Armory, and produced the excellent SAR-48 copy of the FN FAL rifle for Springfield, which was imported from 1985 to 1997. A plan to build M6 Scout rifle-shotgun combos for Springfield Armory unfortunately fell through in the late 1990s, but the surviving samples have become collectible.

Domestic brands like Taurus and Imbel have additional advantages over foreign makes that go beyond price and availability. None of the foreign marques have warranty or repair stations, for example, and there’s often no ready supply of spare parts or accessories (including essentials like magazines) for the foreign brands. If the Brazilian gun market is allowed to flourish under President Bolsonaro, this could change for the better, but for now it gives the “home team” a significant logistical advantage.

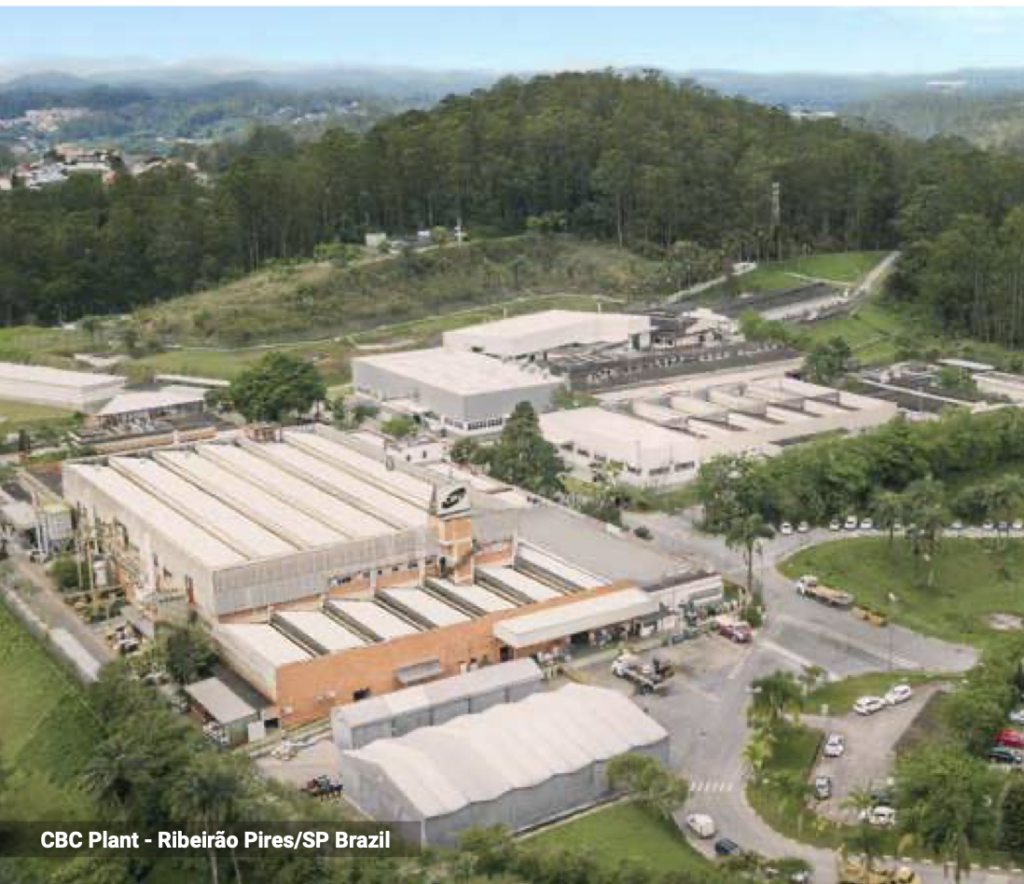

There is a single domestic manufacturer of ammunition in Brazil. CBC (Brazilian Cartridge Company) manufactures ammunition for the military, law enforcement and commercial markets, and is the principal company of CBC Global Ammunition, which includes other brands such as Magtech (Brazil), MEN (Germany), and Sellier & Bellot (Czech Republic). Many Americans recognize the Magtech label, as the ammunition is widely available here (at least when we’re not in the middle of an ammo crisis). The Magtech ammunition is loaded by CBC in Brazil, and exported under the Magtech label, while ammunition intended for the domestic market is sold under the CBC marque.

Since the Bolsonaro relief, the CBC monopoly in the Brazilian ammunition market has been challenged, and some foreign labels are starting to become available in Brazil. Brands such as Federal and Fiocchi are occasionally encountered now, but supplies are restricted and prices remain very high due to exchange rates and import taxes.

Because factory ammunition is very expensive in Brazil, it’s marketed and sold in smaller quantities. Ten-round blister packs of CBC ammunition are sold to consumers for the same price that an American would pay for a 50-round box of the same product.

The great expense of factory ammunition has promoted a strong reloading culture in Brazil. A special license, issued by the Brazilian Army, is required to purchase reloading components, and a pre-purchase authorization must be received for each transaction, but Brazilians endure the bureaucracy in order to afford shooting their firearms. It would be impossible to afford competing in the shooting sports in Brazil without reloading.

Because of the traditional Brazilian caliber limitations, Brazilian reloaders have a history of loading handgun cartridges beyond approved limits, in an effort to extract more performance. Erick reports that owners of .380 ACP pistols often try to load them to 9mm Luger levels, and owners of .38 Special revolvers often try to load them to .357 Magnum levels, with many shooters damaging or destroying their guns in the process. Erick hopes that these instances will decrease now that the caliber restrictions have been lifted.

Brazilian reloaders have also been masters of economy, reusing fired cases until they crack, then modifying them for use in another firearm. In example, Erick reports that some Brazilian shooters will shorten cracked .38 Special cases, and turn their rims, to create a case that’s suitable for use in .380 ACP pistols!

HANDGUNs in civilian use–Autos

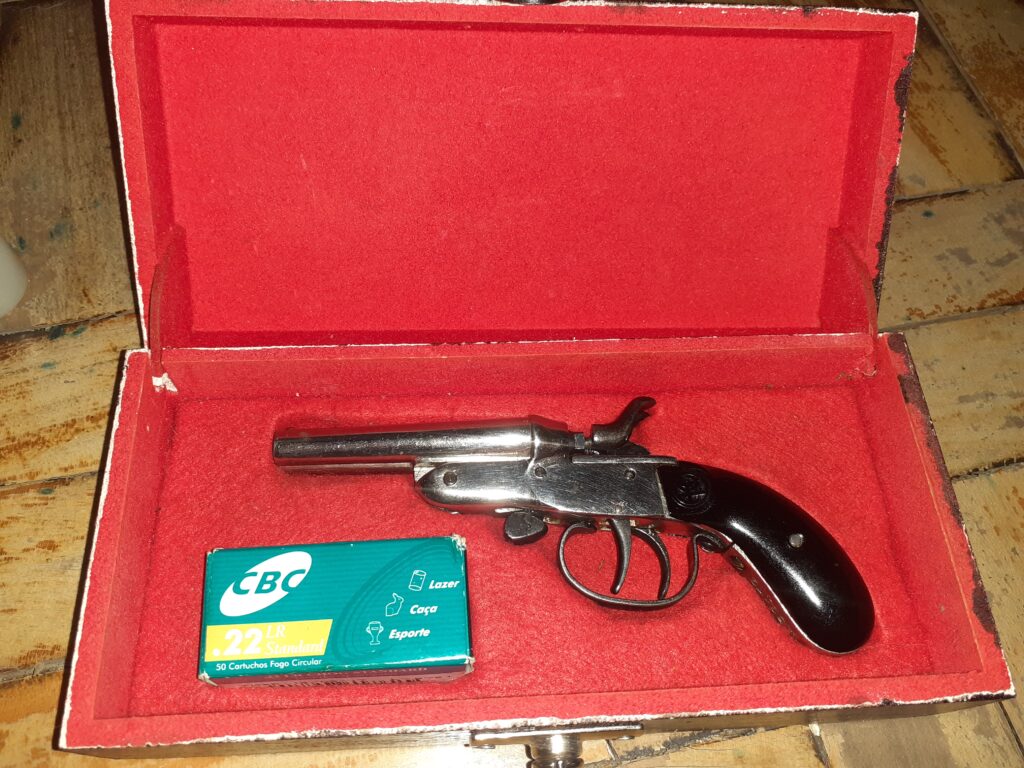

As a result of the prior caliber restrictions, Brazilians own lots of .22 Short, .22 LR, .25 ACP, .32 ACP and .380 ACP pistols.

Since the .380 ACP was the most powerful auto caliber approved for civilian use prior to the Bolsonaro reforms, high-capacity .380 Autos have always been quite popular in Brazil. Guns like the Taurus PT-58 HC/HC Plus (domestically-produced pistols, patterned after the 13-round Beretta 84, with magazine capacities of 15 / 19 rounds), Imbel GC (a family of domestically-produced 1911-style pistols with magazine capacities of 17 to 19 rounds), Glock 25 (a .380 ACP version of the Glock 19, not available in the United States), Argentinian Bersa pistols (15+1 capacity in the largest models), and Czech CZ-83 (a high quality, 13+1 auto which was imported into Brazil in the 1990s, but infrequently encountered) have been popular with citizens there.

One might suspect the excellent Beretta 84 would also be popular in Brazil, but they have always been in short supply, because of import restrictions and cost. There was once a Beretta plant in Brazil, which made Model 92 pistols and PM12 submachineguns for the Brazilian military, shotguns for civilians, and .22 Short and .25 ACP Model 950 pistols for the civilian market, but no Beretta 84s were produced there. The plant was acquired by Taurus in 1980, and has therefore produced nothing but Taurus products for the last 40 years.

In the early 1980’s, the domestically-produced Taurus PT-57, a .32 ACP version of the 9mm PT-92, was also popular in Brazil, by virtue of the fact that civilians were not allowed to own .380 ACP pistols until December of 1987.

These large .32 ACP and .380 ACP autos were so popular in Brazil, that the Brazilian Shooting Federation created a special IPSC category for them, named IPSC Light. Experience in these games indicated that the .380 ACP suffered from poor accuracy, and thus, .32 ACP pistols were preferred by many of the competitors. Erick reports that some of the best large-frame .32 ACPs are actually capable of shooting as well as .32 S&W Long revolvers loaded with wadcutters.

In the wake of President Bolsonaro’s executive order, Brazilians are now trying to purchase domestically-produced 9mm Taurus pistols and (less frequently) 1911-style, .45 ACP Imbel pistols to upgrade their armament. The most wealthy Brazilians seek to buy the Glock pistols that are being increasingly imported into the country ($14.8 million worth, in the first half of 2020). The supply of foreign-made pistols is very limited, and they are very expensive, due to import taxes and the relative weakness of Brazilian currency.

HANDGUNs in civilian use—Revolvers

The caliber restrictions traditionally imposed on Brazilians left a lot of them armed with .22, .32 and .38 caliber revolvers. The early, Vargas-era caliber restrictions created a gun culture where the .32 S&W Long was especially common in Brazil, but the 1965 approval of the .38 Special made this cartridge the most popular revolver cartridge in use.

Since the .38 Special is more powerful than the .380 ACP—particularly when following the Brazilian practice of loading ammunition “hot”—the revolver has always enjoyed an edge in Brazil, and hasn’t lost as much ground to the autopistol as it has in other gun cultures, where calibers were unrestricted.

The most popular revolvers in Brazilian use have always been the domestically-produced Taurus and Rossi revolvers, for obvious reasons. Americans might remember the Rossi revolvers that were imported by Interarms for decades, and for a short while by Braztech International. Taurus purchased Rossi in December of 1997, and continued to make Rossi revolvers for a few years, but eventually discontinued them. Rossi still makes long guns for export, but their domestic business consists solely of airgun imports, now.

As a result, Taurus has a monopoly on the domestic revolver market in Brazil. As we’ve seen in the United States, the reputation of the Taurus brand has risen and fallen at various times among Brazilian shooters. Erick believes the highwater mark for Taurus occurred between 1988 and 1998, when they were making high-quality products (of note: Taurus earned an ISO 9001 certification thereafter, in 1999) but the quality of their São Leopoldo-produced revolvers has declined since the purchase of Rossi (RevolverGuys should understand that Taurus USA manufactures firearms in a different facility—recently relocated to Bainbridge, Georgia, in 2019—and has its own quality control processes).

In the wake of President Bolsonaro’s executive order, Brazilian RevolverGuys are now eager to buy Taurus .357 Magnum revolvers to upgrade their collections, and it’s hoped this will put an end to the number of .38 Special revolvers blown up by aggressive reloaders.

Shooting in Brazil

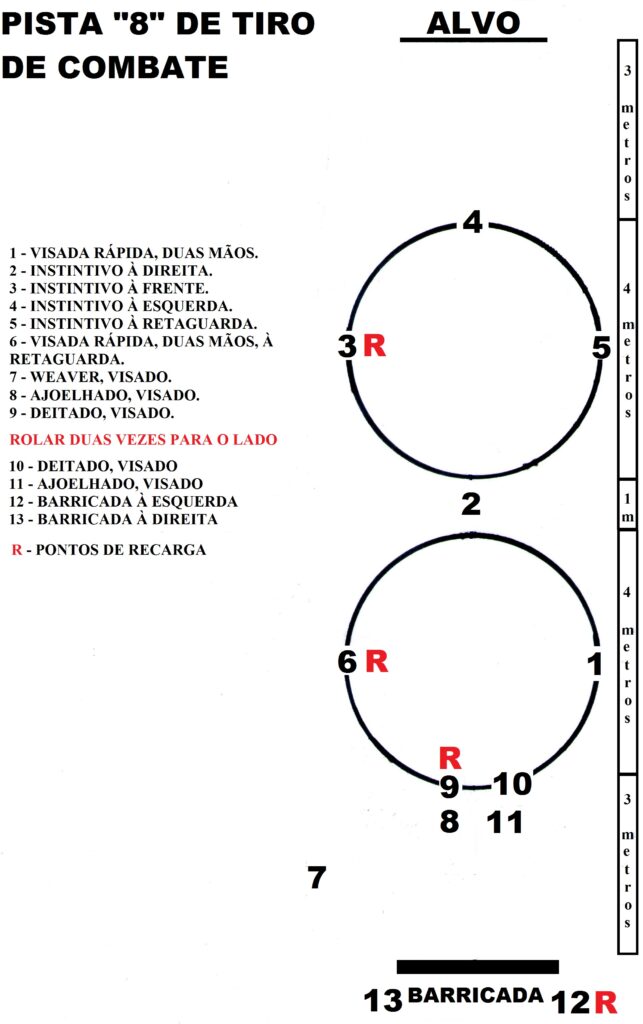

Brazil has a sport shooting culture, with national-level groups like the Brazilian Confederation of Shooting Sports, to guide Olympic-style sport shooting, and the Brazilian Confederation of Practical Shooting, to guide IPSC-style sport shooting.

Public shooting ranges are limited in Brazil, and costs can be prohibitive for some Brazilians. Even law enforcement agencies can struggle to gain access to suitable training facilities. Thankfully, President Bolsonaro’s recent executive order will make it easier for those in rural communities to shoot and train on their own property.

Brazilian revolver slang

Due to the nature of immigration patterns in Brazil, there’s a greater Germanic influence on the language, than English. As a result, Erick says some Anglo jargon is misspelled in a Germanic fashion, with Brazilians commonly referring to “Schmidt & Wesson” revolvers, for example.

As with any culture, Brazilians have their own slang for many revolver-related terms. Erick shared the following ones with us:

-

-

- Canela Seca (“Dry Shin”) or Pescoço de Frango (“Chicken Neck”): A revolver with a thin barrel profile;

- Pica-pau (“Woodpecker”): A revolver with firing pin on the hammer, instead of a frame-mounted firing pin. This term also refers to a homemade, muzzle-loading shotgun used in poor rural areas. (Note: Erick advises that the term “direct percussion” is used in Brazil to describe firearms where a one-piece hammer or striker contacts the primer directly, and “indirect percussion” is used to describe firearms where a hammer strikes a separate firing pin, which then contacts the primer. This distinction was once important to government authorities who mistakenly believed that “direct percussion” systems were inherently less safe than “indirect percussion” systems. Like Erick, we understand that the safety features which are designed into a gun are more important than the ignition system, when it comes to determining the safety of a design. A hammer-fired gun with an unrestricted firing pin, that can inertia fire, is certainly less safe to drop than a striker-fired pistol with a firing pin block and other internal safeties, for example. Erick explains that the example demonstrates how government authorities can sometimes have an immature or flawed understanding of the technical aspects of firearms—something we are also very familiar with, here in the United States!);

- Bulldog: This British term is used in lieu of “snubby,” to describe short-barreled revolvers;

- TA.: An abbreviation for the Taurus “Tiro ao Alvo” (Target Shooting) revolver, which is based on the S&W K-22/32/38 series. This term is commonly used to describe any revolver with a 6-inch or longer barrel;

- Diabo Paraibano (Paraíba-state Devil): A cartridge with a wadcutter bullet, loaded backwards. This term is used in the Northeast Region;

- Mocho (exact translation unavailable): In livestock, this term refers to cattle without horns. When used to describe a gun, it means a hammerless (or an internal hammer) gun, especially a double-barreled shotgun;

- Orelha de Porco (“Pig Ear”): A military-style flap holster;

- Cavalinho (“Little Horse”): Any Colt-made gun, but most often applied to the Police Positive model;

-

Flobert: Inspired by the last name of the Frenchman who created the first rimfire cartridge in 1845, this term is frequently used in rural areas to describe any rimfire gun, especially.22LR rifles;

-

Caixa de Pau (“Wooden Box”): The Brazilian equivalent to “Broomhandle,” applied to Mauser C-96 pistols, especially in the Northeast region of Brazil.

-

Law enforcement in Brazil

Brazil is a federal republic, which is composed of 26 states and a federal district. Some law enforcement agencies in Brazil are under the control of the federal government, while others are under the control of the state governments.

Per Article 144 of the Brazilian constitution, federal police forces include the following organizations:

-

-

- Federal Police of Brazil: Similar to the American FBI, this agency enforces laws concerning international drug trafficking, terrorism, organized crime, and crimes against federal interests. It is also responsible for border security, airport security, and immigration control. If a crime is committed against a federal authority, a public institution, or a foreign authority or company, the Federal Police will conduct the investigation. The Federal Police may occasionally investigate interstate crimes as well, but these are usually handled by state police agencies;

- Federal Highway Police: This agency patrols and enforces the law on federal highways;

- Federal Railway Police: This agency is not currently active, but still exists as a legal entity in the Brazilian constitution;

- National Security Force: This is a temporary emergency force, comprised of personnel borrowed from federal and state agencies, that can be mobilized to deal with national-level public crises, or to augment state police agencies during a large contingency.

-

The state-level police agencies in Brazil include the following:

-

-

- Military Police: The Military Police are uniformed patrol officers, who handle typical law enforcement duties in the states and the federal district. They wear state-specific uniforms and their activities are directed by the state governments. While they are technically a reserve component of the military, which can be recalled to federal service in time of war, their primary directive is civilian law enforcement and crime prevention. In some states, like São Paulo, the fire department is also part of the Military Police;

- Civil Police: The Civil Police are responsible for all detective work, forensics and criminal investigations in the states. They work in plainclothes, and are generally divided into Territorial Units (which investigate all crimes inside jurisdictional boundaries) and Specialized Units (which focus on crimes such as homicides, bank robbery, and kidnapping, without jurisdictional limitations). Our RevolverGuy friend, Erick, is currently a detective in a Specialized Unit, known as the Divisão Anti-Sequestro (DAS—Anti-Kidnapping Division), after serving 11 years as a detective on the Homicide Division;

- Municipal Guards: These security officers protect municipal buildings and services, such as schools and hospitals.

-

Police firearms in Brazil

Because of the high levels of violent crime in Brazil, police officers in the country are typically required by policy to carry firearms at all times, even when they are off duty. Some state agencies may not require this, as a matter of policy or simple logistics (there are some agencies who cannot afford to issue every officer a handgun, so officers are issued a handgun for duty, and required to turn it in after duty), but in most places in Brazil, police officers routinely carry handguns on and off the clock.

Firearms are issued to police officers by their agencies, but police officers may also privately purchase firearms for on and off duty use. The laws which restricted calibers also applied to police officers who wanted to purchase firearms for private use, so many police officers were unable to carry anything larger than a .380 ACP or .38 Special. Fortunately, the Bolsonaro relief is changing this for the better.

Firearms training is limited, due to budgetary concerns. Some police officers will spend their own money and time to practice shooting on private ranges, just as we see here in the United States. Some things never change, regardless of where you are in the world!

Handguns used by Brazilian police

Through the 1990s, Brazilian police officers (both federal and state) were typically armed with 4” .38 Special revolvers (Rossi or Taurus), and (after 1987) carried privately-purchased .380 Autos for additional firepower, when desired.

However, some agencies issued or authorized autopistols and revolvers in larger calibers. The Federal Police, for example, issued Taurus PT-92 pistols in 9mm beginning in the 1980s, and later transitioned to Glock 17 and 19 9mm pistols in the early 2000s. Some state-level Specialized Units provided Imbel (M1911A1) and Taurus (PT-945) pistols chambered in .45 ACP, or Taurus revolvers chambered in .357 Magnum, and authorized officers to use confiscated arms in various calibers. Our friend Erick, for example, carried a .45 ACP 1911 for 10 years, and a confiscated, 9mm Heckler & Koch VP70Z for four years, as a homicide detective, before transitioning to a .357 Magnum revolver in his current assignment with the anti-kidnapping division.

When the Federal Highway Police began a transition from .38 Special revolvers to .40 S&W pistols (Taurus PT-100 and PT-940) in 1998, they started a movement that swept throughout Brazilian law enforcement. Soon, the Military and Civil Police followed suit, and began to replace their .38 Special revolvers and other varied handguns with .40 S&W caliber pistols made by Taurus (including the more compact PT-640 and 24/7 models) Imbel, or Glock (some specialized units in the Civil Police are just starting to get Glock 22s issued). This conversion from .38 Special revolvers to .40 S&W autos is still underway in some agencies.

The .38 Special, .45 ACP and .357 Magnum handguns once authorized by the Civil Police are now being phased out in favor of .40 S&W caliber guns to ease logistics. Agencies will consolidate to a single caliber, .40 S&W, and will no longer be purchasing .45 ACP or .357 Magnum ammunition. When the ammunition for these guns runs out, officers will be forced to switch to .40 caliber guns.

Our streetwise, RevolverGuy friend Erick advises that he’s going to hold out as long as he can with his .357 Magnum revolver, however. The Taurus .40 S&W pistols don’t have a very good reputation for reliability, and while the Imbel 1911-style pistols in .40 S&W are more trustworthy, their size and weight make them difficult to carry in plainclothes. Erick is very happy with the size, weight, and performance of his .357 Magnum, and has no intention of trading it for one of these autos. He notes that the double action revolver is colloquially known as the “resolver” in Brazil for an important reason—it can always be relied upon to fix (resolve) problems!

Erick also notes that the .357 Magnum is especially effective against criminals in vehicles, which is very important to him in his current assignment. Apparently, the .40 S&W ammunition that’s available to police in Brazil suffers from core-jacket separation when it’s fired into glass and steel, and the Magnum ammunition outperforms it. This capability should come as no surprise to RevolverGuys, as the .357 Magnum has always had a good reputation for automobile penetration, dating back to its first use against the motor bandits of the 1930s.

With the Federal Police sticking with their 9mm Glocks, and everyone else transitioning to .40 S&W pistols, the .38 Special revolver’s future is limited in Brazilian law enforcement. The Municipal Guards, prior to President Bolsonaro’s executive order, were restricted to “civilian” calibers only, and thus carried large numbers of .380 Autos and .38 Specials, but will slowly transition to more effective arms now that the caliber restrictions have been eliminated.

Long guns used by Brazilian police

Brazilian police also have ready access to long guns, and the extreme violence in some parts of the country make them essential. As Erick observed, “Rio de Janeiro is about 250 miles from São Paulo, but appears to be another country. Rifles are essential there. There’s no police car without a 7.62mm NATO FAL.” The persistent problems with hijacking and robbery of transport trucks on the highways (with some bandits even using .50 caliber Browning machineguns) has also made it essential for Federal Highway Police to be armed with suitable rifles.

Within the Civil Police, specialized units, like the Bank Robbery Unit, are also commonly equipped with rifles.

Imbel-manufactured, FAL-pattern rifles are prevalent throughout Brazilian police forces. Some of these are traditional para-rifles with folding stocks, chambered in 7.62mm, while others are improved FAL patterns chambered in 5.56mm, like the Imbel IA2. Some forces also reportedly use foreign weapons like the Colt M4 carbine, Colt M-16 rifle, and Heckler & Koch G3, G36, HK416 and HK417 rifles.

Some shotguns are in use, particularly the CBC/Magtech-produced Model 586 12 Gauge pump shotgun. These weapons are particularly common in São Paulo, according to Erick, and are frequently used in correctional facilities, in addition to patrol.

Brazilian police also have a number of submachineguns (SMGs) in inventory as well. One of the most commonly-encountered guns is a locally-produced variant of the Chilean FAMAE SAF, a 9mm, blowback SMG that’s based on the Sig SG 540 rifle. The guns you’ll find in Brazil are actually licensed copies of the FAMAE SAF, produced by Taurus, known as the Taurus MT40. The Brazilian guns differ from the original design, in that they’re chambered in .40 S&W. Erick advises that the high cyclic rate of these guns (around 1,200 rpm) makes them difficult to control in anything other than the semiauto or three-round burst modes.

There are reports that the MT 40s haven’t withstood heavy use in training environments like the police academy, where they are fired often. Apparently, the fire selector is prone to malfunction, with the three-round burst mode giving unpredictable results (sometimes full auto, sometimes a higher or lower number of rounds), and the guns have cracked from the stress induced by firing such a high pressure round at such a high cyclic rate. Taurus now builds an MT 40 replacement , called the SMT 40, which offers no parts interchangeability with the earlier gun, save the 30 round magazine. Externally, the SMT 40 has a different folding stock, a hew hand guard with Picatinny rails, and a redesigned magazine well that incorporates a fore grip. It appears to have ambidextrous controls, and Erick advises the cyclic rate has been reduced for greater control. Strangely, it too has had issues with the fire control lever. It’s reported that some samples will fire when the safety is moved from On Safe to Off Safe, if the trigger was previously pulled when the weapon was On Safe—a dangerous defect that’s previously led to recalls on some other guns here in America, too.

Holsters and accessories used by Brazilian police

As in the United States, police duty holsters were traditionally made of leather in Brazil, but synthetic materials, like nylon fabric, are increasingly used these days.

In the 20th Century, most police duty holsters followed the military pattern, with large flaps to protect the gun. Holsters made for revolvers frequently included cartridge loops under the flap for spare cartridges, or sometimes placed the loops on the exterior of the holster. Many of these police duty holsters were designed with metal hooks that would allow the holster to hang from a military-style web belt.

By the 1990s, open top holsters with simple retention devices became more popular in police use. Unfortunately, police duty holsters with advanced retention features, like those made here by Safariland, are not yet common in Brazil.

Concealment holsters for plainclothes work or off duty wear are locally made from leather and synthetics. Unfortunately, Brazilian police do not have access to the wide variety of quality designs that we have here in the United States, and many of their concealment holster choices would seem unsophisticated compared to the products available here.

Inside-the-waistband (IWB) holsters that are made in Brazil typically use metal spring clips or wire clips to secure the holster to the belt. Belt loop attachments are rarely used, and only then on expensive, custom-made holsters. Erick has found that he prefers the wire clip to a metal spring clip, because the wire-style allows him to thread his belt through the clip for better stability and retention. Erick reports that as autopistols continue to make more inroads into policing in Brazil, it is getting harder to find quality revolver holsters for concealed carry.

The standard ammunition load for a police officer in Brazil is to carry two reloads for the duty gun. Police officers who carry revolvers often carry their spare ammunition in locally-produced copies of the JetLoader speedloader, but many officers are still using cartridge loops to carry their spare revolver ammunition—particularly the Municipal Guards that are still armed with revolvers. Strip-style loaders, like the Bianchi Speed Strip, never achieved much popularity in Brazil and are rarely encountered.

Erick advises that he carries his spare .357 Magnum ammunition in JetLoaders, usually in a jacket or pants pocket, as a plainclothes detective. However, when conducting raids or other operations, he has a pouch for the loaders on his ballistic vest. On those occasions when he’s serving as a firearms instructor, or is wearing casual clothing, a photographer-style vest is often worn and the loaders go into the pockets. Some of the pockets, designed to carry film canisters, are useful as makeshift speedloader pouches, particularly when lined with a short piece of plastic PVC pipe to make drawing the loader easy.

Erick advises that 2x2x2 pouches are virtually unknown in Brazil, but early in his career, he was taught to use a 3×3 loading technique from standard belt loops that was effective. The veteran officer who taught him the technique grabbed three rounds from the loops in the same way that a half-moon clip for a S&W 1917 revolver would be held, with thumb underneath and the cartridges arranged in an arc, under the fingers. This veteran officer was able to complete a 3×3 reload using loose cartridges very quickly with this method. Although Erick usually relies on his JetLoaders, he continues to practice reloads with loose rounds carried in loops, in case the skill is needed.

A homicide detective’s observations on ammunition

As a veteran homicide detective in a nation with one of the highest murder rates in the world, Erick has seen a large number of gunshot wounds and has developed a number of useful insights, based on his experience.

It should be noted that Erick’s experience is influenced by the ammunition available in Brazil. The vast majority of the ammunition used in shootings in Brazil is manufactured domestically by CBC, and the remainder is likely military surplus from ComBloc nations, illegally imported by the smugglers and criminals who bring foreign military weapons into the country.

While CBC is one of the largest ammunition concerns in the world, its jacketed hollowpoint designs are not sophisticated by American standards, and don’t perform as well as premium products like Winchester PDX1, Hornady Critical Defense/Duty, Speer Gold Dot, Corbon DPX, or Federal HST. The CBC/Magtech hollowpoints frequently fail to expand when tested in gelatin, and act a lot more like ball ammunition than hollowpoints.

Since most of the ammunition produced by CBC and foreign military sources is loaded with FMJ or RNL bullets, and since most of the hollowpoints produced by CBC fail to appreciably expand, a lot of Erick’s experience is based on shootings with non-expanding ammunition. In the United States, criminals frequently use non-expanding ammunition in their guns (perhaps as much as half the time, according to some studies) because it’s inexpensive or easy to obtain, but readers should understand that Erick’s observations may not be directly applicable to shootings with premium hollowpoint ammunition that expands reliably.

That said, here are some of Erick’s unfiltered observations from the violent streets of Brazil:

-

-

- Almost 90% of gunfights that I followed was with .38 Special, .380 Auto and .40 S&W calibers;

- Hollowpoint ammo does not work well in .380 Auto and .38 Special, because are incapable to expand AND penetrate adequately at the same time. When the expansion works, the penetration is not deep enough. It should be considered, for example, if the forearm is hit before the torso. In these calibers, I prefer standard weight bullets (95/158 grains) than the lighter ones. My Walther PPK is loaded only standard FMJ ammo. For .38 Specials, my favorite load is +P 158 grains HP. It´s effective even if does not expand, acting like a flat point;

- The .40 S&W is brutally effective with 155 grains HP, but only in direct fire. Through light barriers, like car windshields, the lead goes out from the jacket. The same applies to .45 ACP, in lesser degree;

- Here, still there is a fear of overpenetration of 9mm Luger. Because this caliber was, by many decades, restricted to military and law enforcement use, average people believe in exaggerated myths;

- .357 Magnum caliber is best for shooting into cars;

- I tried to reproduce Marshall & Sanow methodology, but failed for a single reason: One-shot stops are extremely rare. Gunfights with one-shot stop are so rare that are not enough to make a reliable statistics, so I developed another method. I noted that there are almost constant number of impacts by caliber. The .380 Auto victims, as a rule, went down with 4 shots. With .38 Special, 2 or 3 shots, depending of physical shape of victim. With 9mm Luger and above rarely exceeds 2 shots. But, of course, there´s exceptions, in both extremes;

- CBC/Magtech now makes solid copper bullets, but the practical results are inferior to standard HP ammo. I believed that all copper bullets are too light. Recently, CBC released a new ammo line, with core and jacket bonded to avoid separation on indirect fire. Bonded ammo is giving good results;

-

Erick also provided the following anecdotes to describe the unpredictable nature of gunfights and terminal ballistics:

-

-

- For example, I investigated a murder. He was hit with a single shot of a .25 Auto FMJ, that passed between the forearm bones and hitted the heart. The victim falled dead in the same place when was shot.

-

Another time, a drug dealer falled down only with SIX 12-gauge slugs fired by a Narcotics officer, the last shot severing the heart and spinal cord. Very hard to explain to the District Attorney…

-

-

- Years ago, a friend shot a felon in the head, using .38 Special Gold Magtech 125 grains +P ammo in a Taurus 85 S. The criminal was using a motorcycle helmet. The bullet expanded inside the helmet and hitted the felon’s head like a rock.

-

The criminal dropped unconscious, but, in the hospital, the bullet felt on the ground when the helmet was removed. Skin was pierced, but not the skull bones.

Would be an excellent helmet or a bad ammo? Maybe both?

Besides a good chuckle (cop humor is the same, all over the world!), what can we take away from this? We think it’s interesting that despite the significant differences between Brazil and the United States, there are striking similarities between Erick’s observations on the effectiveness of various calibers and what we’ve seen in shootings here:

-

-

- Low energy calibers like .380 Auto and .38 Special tend to be less efficient than the more powerful service calibers at stopping threats;

- It’s difficult to achieve both penetration and expansion with calibers like .380 Auto or .38 Special, so sometimes it’s a reasonable choice to use non-expanding ammunition in these guns;

- If you’re likely to have to engage someone who is in a car, your ammunition needs to be capable of penetrating steel and glass, with enough mass and energy remaining, to stop the threat. This calls for powerful cartridges when shooting “dumb” (unsophisticated design and materials) ammunition, or “smart” (tough, well-designed, barrier-blind) bullets in less-powerful calibers;

- Auto glass is very tough on bullets—the toughest barrier to penetrate. Bonded bullets are a help, here;

- Gunfights and terminal ballistics are unpredictable, so don’t expect much from your ammo—especially your handgun ammo. Shoot until the threat stops being a threat;

- Finally, it’s better to be lucky, than good! Murphy lurks everywhere!

-

WRAP UP

We are so thankful that Erick shared his valuable knowledge and experience with us here at RevolverGuy. It has been wonderful to learn about the gun culture in his country and to benefit from his valuable expertise.

It has been particularly fascinating to look inside a gun culture where the revolver is still just as prevalent as the autopistol, even in some police circles, because of government restrictions, supply limitations, ammunition quality, and the weaknesses of the available autopistol designs.

In some ways, Brazil is a time capsule that captures the state of gun and ammunition technology in America in the 1970s to early 1990s. In other ways, Brazil appears to be a harbinger of the future in some of the American states that are more hostile towards guns and gun owners. It’s a fascinating juxtaposition, and there’s a lot for American gun owners to consider there, and learn from.

We’d like to thank Erick again for his time and help. We’re very proud to have him as part of the RevolverGuy family. We wish him and his fellow Brazilian police officers and shooters the very best, and hope their firearm freedoms will continue to expand.

*****

March 2023 Postscript: Sadly, the good citizens of Brazil are once again in jeopardy of losing their firearms and civil liberties, after the problematic and contested election of left-wing President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who is making moves to confiscate legally-owned and registered firearms. Brazilians have seen this familiar story before, and we hope they will succeed in defending their liberty and guns from their own government.

July 2023 Postscript: As described in recent reports, left-wing President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has signed a decree that restricts civilian possession of firearms and places new restrictions on commercial shooting ranges. The decree:

Reduces the number of guns civilians can possess for personal safety from four to two, reduces the allowed ammunition for each gun from 200 rounds to 50 and requires documentation proving the need to hold the weapons. It also bars civilians from owning 9 mm pistols, restricting them to members of the police and military.

Additionally:

[Shooting ranges] can operate only from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. and must be at least 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) away from schools. Lula‘s new policy also changes the duration of a gun permit from 10 years under Bolsonaro to new limits of three to five years, depending on the holder.

Furthermore:

Lula‘s government is encouraging citizens to sell firearms that are not allowed under the new rules before the end of the year or face confiscation by the Federal Police. The new rules also solidify the status of the Federal Police as official watchdog over guns, sidelining the military, which previously held that role. In May, Lula‘s justice minister had imposed a deadline for citizens to legally register firearms with the Federal Police. That previously was typically done by the military, but Lula‘s new left-wing government has cast doubts on the reliability of the armed forces in carrying out that function because of the tendency of many of their members to support Bolsonaro.

Mega Thanks to Erick for taking the time and effort to help Mike put this article together. Erick, you have given us a tremendous insight into the state of thing in Brasil, both socially, with gun policy orientation, and the evolution of law enforcement firearms use in general. You have made a smart choice with the .357 Magnum. In the years I carried the .357 on duty, I never saw, or read of anyone get up after being hit by one.

While I personally have not had very good experiences with Taurus guns in the U.S., I have had nothing but excellent results with those made by Imbel ! Their FAL receivers are superb, and they also make one tough M1911A1 pistol.

Hopefully, the regulations in Brasil will gradually decrease, and more ordinary citizens will be allowed to carry to protect themselves and families. It might even spill over to other countries in South America (we can hope)

Seja seguro e observe suas costas

Thank you and Erick both for a very interesting and informative article.

There was one S&W revolver that was sent to a LE agency in Brasil that had a unique configuration. It is a model 10-10 with a 3 inch barrel and round butt. The feature that is unique is that it has an enclosed ejector rod.

Would be interesting if Erick might know which agency used these and if they are still in use.

A few were released into the US and I was fortunate to pick one up. Estimates in US range up to 50 examples. My favorite.

Thank you, Bond!

I’m proud to work with Mike and RevolverGuy!

Tony,

Officially, the last S&W duty revolvers went to Brazil during World War 2, both S&W 1917 .45 Auto Rim and Military & Police .38 Special. I never heard about the described S&W. Do you know its year of production?

After WW2, the “importation substitution” policy was adopted. Between end of 194o’s and beginning of 1990’s, virtually no imported handguns were used by our law enforcement agencies.

Some long guns, like Browning pump shotguns and earlier Beretta M-12 SMGs are imported in the beginning of 70’s, but virtually no handguns. Others was sent by USAID (like S&W M-76 and Ingram SMGs) to help fight left-wing guerrillas in 60’s and 70’s.

Shrouded extractor rods are very uncommon here before 1975, when Taurus released .357 Magnum guns.

Tony,

The only S&W specially made to Brazilian market that I know is a .38 Special-only version of 586, that was imported in the middle of 90’s. Models originally in .38 Special was also imported at that time – including Baby Sigma .380 pistol – but in its original configuration.

But S&W revolvers are deluxe items, because it costed twice-and-half than a Taurus or Rossi.

I don’t believe that its different configuration was made by any Brazilian LE agency, because our laws obliges to favor locally-made products for public institutions purchasing. Imported ones are allowed only if there’s no similar locally made.

Thank you Erick,

This is a fascinating look at something I have wondered about. I too would stick with .357, it just seems authoritative. Stay careful Sir.

Erick,

Page 205 of the 4th edition of the “Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson book by Jim Supica & Richard Nahas under Model 10 specials & variants has this entry ,

Brazilian Contract: Model 10-10: with full lug (half) 3” barrel and full length extractor rod, round butt, special production 1994 Product code: 100134.

Have not seen a factory historical letter but according to others Mr Roy Jenks, S&W Historian, indicates this order was for Brazil. More information can be found on the Smith & Wesson Forum.

Thank you again for your information about the guns of Brazil.

Stay safe!

Tony,

There’s no official contract with S&W and Brazilian LE agencies in the 1990’s, but Rossi de Moraes Imports (not Rossi Firearms) imported S&W revolvers (and Baby Sigma pistol), handcuffs, and Interarms Walther pistols for civilian market.

I’m trying to find a catalog of that time, but I remember that 586-5 (.38 Special only) was the only S&W revolver modified to Brazilian market, due the .357 Magnum restriction laws at that time. I saw only Models 10, 15 and 640 sold in Brazilian stores at that time.

Indeed, only wealthy people bought S&W revolvers and Interarms Walther pistols at that time, but no LE agency.

As I said before, our laws does not allow to LE agencies to buy S&W revolvers, because there’s cheaper, countrymade similars, like Taurus and Rossi.

I was told by US State Dept. Security gunsmiths that these special-order S&W revolvers were intended for issue to Brazilian diplomatic security personnel in the USA, Canada and EU. Brazilian security personnel stationed at diplomatic missions in the US were granted access to US government training facilities. S&W revolvers were purchased to facilitate this so that spare parts and service could be maintained and that any necessary spare parts, tools and fixtures could be made available to them as a professional courtesy.

Excellent! I don´t knew it!

In 2016, I trained security personnel of US Consulate in São Paulo. US Marines works in the internal area of Consulate, but the external security work is provided by Brazilian Security firms – armed with Taurus 82 revolvers.

We followed the training program given by Consulate Military Attache, not the standard Brazilian training program for private security. Distance measured in yards (not meters) and targets provided by US Government (representing an Arab carrying a Kalashnikov rifle!).

The training was supervised by a female Marine Staff Sergeant, who provided all the logistical support. It was a great experience, because, contrary to what happens in the Brazilian police training, there was no lack of resources. Any requests for material were answered with a “no problem” and were available quickly.

Within the same logic of dividing areas of responsibility, it is likely that the users of these revolvers were Private Security personnel hired by the Diplomatic Corps.

The internal security of Brazilian Embassies and Consulates is responsibility of Federal Police (our equivalent to the FBI), whose standard service handgun in the 1990s was the Taurus PT-92 pistol.

Erick, thank you for the EXCELLENT education about the gun culture in your country!

The normal way for the Brazilian government to acquire these guns would be through the Ministry of Justice or the Ministry of the Army.

Due to this specific destination, it is more likely that the purchase was made by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This would explain the fact that they are not included in the inventory of any police or military force.

Erick and Mike,

Thank you very much for the informative read on the guns and gear of Brazil. Erick, I hope that the trend you are now seeing towards lessening restrictions continues. It makes me very much appreciate how good we have it here in the U.S.

I especially enjoyed the section on revolver slang, being a fan of the Pescoco de Frango!

Thank you Erick for your insight that enabled this article to be written. Despite having never been to Brazil myself, nor speaking any Portuguese, it is a country I find myself interested in. I’ve researched what I can of Brazil’s history and life there, and in some respects I find it to be not too dissimilar from the US. This article provides additional, and much appreciated, perspective into Brazil. Thank you again Erick, as well as Mike for writing this article.

Correction: a friend sent to me a 1996 catalog of S&W guns imported to Brazil.

The S&W importer was Realiza, not Rossi de Moraes – that imported Interarms Walther pistols.

Thank you fellows for all of this fascinating stuff.

The 3 + 3 reload technique mentioned in this article sounded familiar from somewhere. Then I recalled that is how Jack Weaver, pioneer of the Weaver Stance, is said to have reloaded his K-38. According to Jeff Cooper he could do so very quickly.

Yes, I read that Weaver reloaded this way too! I think on Elden Carl’s blog?

Mike–yes sir, I think I read it there, also in Cooper on Handguns.

Terrific and extremely informative article! Top notch!

Erick,

Thank you for sharing the info on Brazil’s current firearm situation/laws. I was raised there but left in the mid 90’s and had lost touch, although I still have a copy of Legislação Brasileira Sobre Armas & Munições by Ennio Murta, the 2a Edição Ampliada, Actualizada e Comentada as published by Editora Magnum.

It was always fascinating to me to see the laws and to see the “enforcement” of the same as just about every item prohibited by law was to be found in the possession of the rich and politically connected. I recall, for example, a Ruger Speed Six in 357 magnum that was not only in civilian possession but also had a carry permit issued by the state of Ceará.

Growing up in a remote area of Brazil exposed me to a lot of firearms history, much of which I could not appreciate in full until we left and I gained a greater access to information regarding some of the items I observed over time. There was an interesting number of pre-WWII weapons around, including a Mauser C96 with wooden stock/holster in 7.62 Mauser caliber, a Walther P38, various Mausers and innumerable shotguns and 22 rifles brought in over the years by all kinds of folks.

Some of my favorites were the old papo amarelo (Winchester 73) and (the slang term eludes me – the Winchester 92) that were so popular with the Seringueros and others. I heard of a Colt Root revolver in the area, but never saw it, probably it was a rusted out relic but would have been fascinating to see. One old store keeper had a S&W hand ejector that was brought into Brazil from Turkey shortly after they were patented (1905 date on barrel, arrived Brazil shortly after – sure wish I had the serial number) He religiously changed the ammo out every year and kept the gun in a holster in the safe. He’d never fired it, but it was terribly rusted on the outside but brand new mechanically with a shiny bore and chambers. Leather in a humid climate does terrible things to steel. The blacksmith shops had lots of items collecting more rust and dust, but some had interesting tales that accompanied them.

Anyway, um abrazo bem grande! Thanks for the memories and the update on the current situation.

I need help with a 22 cal. target rifle made in Brazil. I need someone to tell me the English for up and down….., right and left. It’s an old Biathlon rifle made in Brazil a long time ago!

Thank you

No reference to laws regarding non-residents conceal-carrying handguns. Is there any consideration of this situation?

Highly doubtful, Harry. I don’t know of any nations where this is the case. Even some states here in the U.S. won’t honor permits held by their countrymen from other states!

Concealment carry permits are very, very restricted to civilians, but is possible under some circumstances. Before the communist former -president Lula sign the “Estatuto do Desarmamento” (The Disarming Statutes) in 2005 you could have your permit relatively easy.

President Bolsonaro is trying to pass a new law for firearms regulation wich allows carry permits, but Brazil still has a considerable amount of left wing politicians elected and they are able to sell their souls to the devil if necessary to ban this law.

We have a good leader now one of his sayings is “A well armed people shall never be slaved” and if God help us pretty soon We will have our rights consolidated.

The good people of Brazil are always in our prayers, Lucas! We hope President Bolsonaro will be successful in his mission to restore the right of self defense for all Brazilians!

Hello Erick,

Congratulations to your report about the past and present situation of gun laws in Brazil!

I am a German, living in Brazil since late 2000 and I have the Brazilian CR (collectors-and or shooters license) since 2003 as well as I had a “Porte de Armas Federal” or Federal carry license for a few years.

I liked your report and conclusions of the past and present situation of Civilian gun owners.

I had to live through all the limitations you described so well. Since Bolsonaro’s election our gun world has changed a lot to the positive. I now own guns with formerly restricted calibers, the CR as the federal license to own guns and all CRAF’s as gun registers issued by the Federal Police or Military are now valid for 10 years instead of formerly 3 years, a huge improvement. Ammunition is available in greater quantities too.

I only hope that with a possible change of Government in 2022 we will not be harrassed again, as it was under the Precidencies of Lula, Dilma and Temer.

The only pity is the high pricing of Brazilian made guns and ammo. Many of the Taurus guns are sold in the USA as well for a fraction of the price we have to pay in Brazil. That’s due to a certain monopoly situation, which Taurus and IMBEL use to keep prices up, together with a high taxation of sales.

I lived for some years in the USA and had a concealed carry license there as well as some guns, which I had to sell when I moved to Brazil. I still envy the gun guys there because they live, in comparison, in gun paradise or gun heaven.

Ulrich, thank you for your wonderful and informative report from Brazil! It’s good to hear that you liked the article and found it accurate.

Yes, we have many things to be grateful for, here in America. There are many places with significant restrictions on guns, but we still enjoy more freedom here than citizens in other countries do.

We hope you’ll stay and enjoy the other articles here at RevolverGuy!

Regarding modern holsters, American Handgunner magazine has published several articles about innovators and developments in the modern era. Chic Gaylord was an important designer/maker for the U.S. concealed-carry market in the more-restrictive 1950s-1970s; an article on him appeared in AHG, Sept./Oct. 2015. Scanned copies of this article may be found at Americanhandgunner.com. I wish I could tell you more as holsters are critically important in safely deploying one’s firearms. There must non-trademarked designs that could be used in Brazil. The editor of AHG, Roy Huntington, ex-LE, is approachable by email. Best of luck, Erick.

Thanks, Lee. You’ll see Gaylord referenced in an upcoming article here in these pages. Thanks for writing.