There was no avoiding it. Eventually, we were going to have to discuss the darned lock.

The lock I’m referring to, of course, is the Internal Locking System (ILS) on Smith & Wesson revolvers, which was added to virtually the entire line, starting in 2001. “The lock” is one of the great controversies in the modern history of firearms; A polarizing move that quickly split the community into one of two camps, much like the production changes to Winchester rifles in 1964, or the addition of the “Series 80” firing pin block by Colt’s to the much-beloved 1911 pistol in 1983.

Similar to Winchester and Colt’s in those missteps, the leadership at Smith & Wesson failed to understand and predict the backlash that would follow the new change. The lock inflamed passions, offended sensibilities, and damaged the brand’s sales. Additionally, the problem didn’t go away. Instead, it festered. The offense had staying power.

So, it’s time for a RevolverGuy to weigh in on this topic. As an enthusiast, I have some pretty strong personal opinions about the lock, but I’ll do my best to separate those from the facts as much as possible, and point them out when they creep in.

The British Are Coming

The story of the lock begins sometime around June of 1987, with the acquisition of the Smith & Wesson brand by Tomkins plc, an engineering company headquartered in London. At the time, Tomkins was remaking itself through a series of acquisitions in various, unconnected industries, with an eye towards revenue growth. Among the various divisions under the Tomkins umbrella were those that dealt in automotive parts, bath supplies (pipes, windows, tubs), baking equipment, and–with the Smith & Wesson acquisition–firearms.

The Tomkins acquisition came on the heels of financial trouble under the ownership of Bangor Punta, another conglomerate like Tomkins, which was based here in America. When Bangor Punta bought the controlling interest in Smith & Wesson from the Wesson family in 1965, they expanded into accessory sales, including Smith & Wesson-branded ammunition, holsters, and police equipment (restraints, sobriety test equipment, patrol car sirens and lightbars, riot gear, etc.). Bangor Punta grew the business handily, and by the late 1970s, these ancillary products accounted for about 25% of Smith & Wesson’s sales.

In the early 1980s though, Smith & Wesson started showing signs of distress. The problem was rooted in the Carter-era downturn in the economy, coupled with aging infrastructure and increased labor and material expenses. In short, income was going down, while costs were going up. More worrisome however, was the general consensus that Springfield quality control was taking a hit, and S&W products were no longer being made to their traditionally high standards. Even the most ardent supporters of the brand were admitting in print that standards were declining.

Then, in the mid-1980s, the “Wondernine Wars” kicked off. When Uncle Sam selected the Italian Beretta 92 as the new service pistol in 1985, Smith & Wesson found themselves playing catch up in a high stakes game. Their 39 and 59-series pistols had never been very popular in either the commercial or the law enforcement markets in the U.S., and early models had developed a reputation for spotty reliability. The S&W Second Generation entry into the three rounds of Pre-XM9 and XM9 pistol trials didn’t fare well either, getting bested by designs from foreign makers Beretta and Sig Sauer, which hurt acceptance and sales of the S&W product.

The big nail in the coffin though, was the importation of the Glock 17, beginning in 1985. The radical pistol struggled to gain acceptance from a conservative market at first, but the strength of the design and an aggressive marketing and sales campaign soon catapulted the plastic pistol into the pole position. The commercial and law enforcement autopistol markets were soon dominated by Glock, with Beretta and Sig Sauer taking up large bites of the remainder. Smith & Wesson sales languished, and profits dropped 41% between 1982 and 1986.

The financial difficulties led to Lear Siegler Holdings Corporation (who had acquired Bangor Punta in 1984) dumping the Smith & Wesson brand. Tomkins plc purchased it in June of 1987, and immediately invested in new design and manufacturing technologies to improve the product. They also instituted strict quality control processes. As a result, Smith & Wesson product quality made a drastic improvement, with warranty returns falling as much as 81% for the pistol lines, and 50% for the revolver lines by mid-1989.

So far, life under the Union Jack had generally been an improvement for Smith & Wesson.

The Bad Old Days

But there were storm clouds on the horizon for Smith & Wesson, and it wasn’t long before the collision of two forces finally brought about the conditions that gave us the lock.

The first was continued economic pressures. While product quality had recovered under Tomkins plc, sales continued to weaken. Smith & Wesson had dramatically improved its line of pistols by the time the Third Generation guns were introduced in the late 1980s, but they still struggled to keep up with the foreign competition. By the mid-1990s, the Sig Sauer P228 had become THE pistol in federal law enforcement, and the Glock had become the most popular gun in uniformed police holsters (particularly the Glock 22, chambered in Smith & Wesson’s new, namesake cartridge—the .40 S&W—which S&W had hoped to make a strong comeback with). A failed attempt to go head-to-head with Glock in the mid-to-late 1990s with the ill-fated Sigma not only burdened the company with a costly settlement, but also served to illustrate the company’s struggle to create a competitive pistol design that sold well.

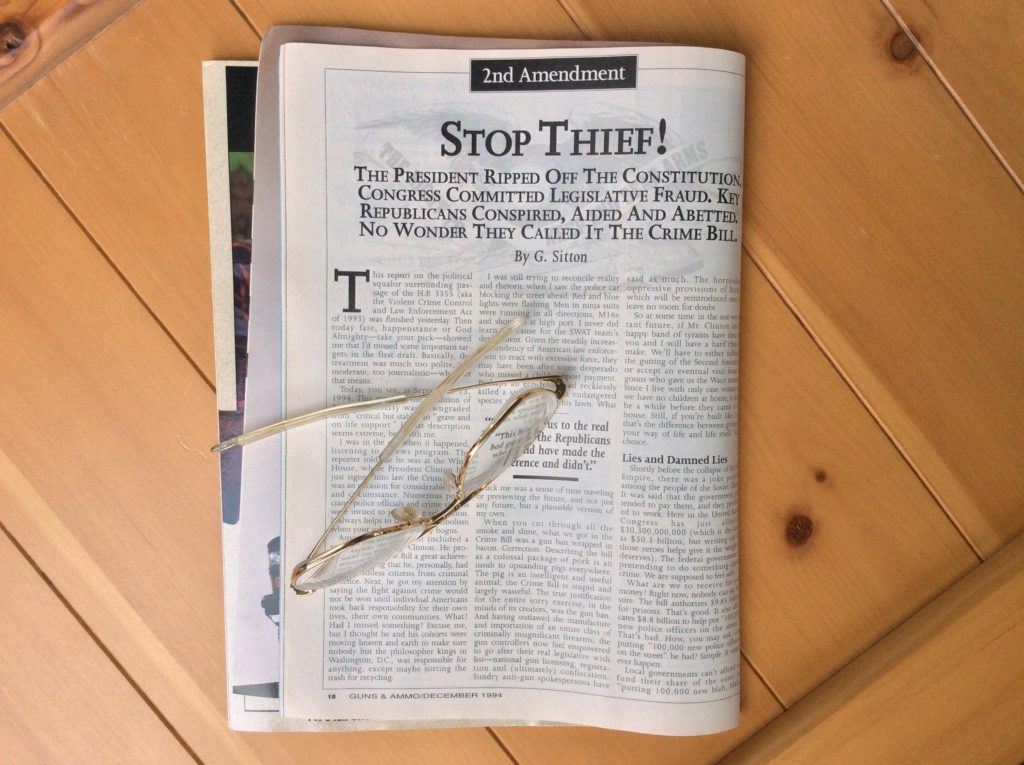

The second force was anti-gun politics. With the November 1992 election of Bill Clinton, one of the nation’s most anti-gun leaders was now in the White House. As President, Clinton quickly called on Congress to place restrictions on the public’s ownership and use of firearms, and less than two years after he took the oath of office, he signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. Part of the Act was a prohibition on the manufacture, transfer, or possession of semiautomatic weapons defined by the legislation, as well as limitations on the manufacture, transfer, and possession of magazines that held greater than 10 rounds.

While the “Assault Weapons Ban” was Clinton’s most significant achievement, the President aggressively pursued a host other anti-gun initiatives as well. Among them, he placed two vehemently anti-gun Justices on the Supreme Court (Ginsburg and Breyer) and filled the lower federal courts with many more. In United States V. Emerson, his Justice Department argued that the Second Amendment only protected the right to keep and bear arms for soldiers serving in the National Guard.

Under his watch and direction, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention turned into a political weapon, funding research that supported anti-gun views (the director of the National Center for Injury Prevention, a division of the CDC, argued that guns, like cigarettes, should be treated as “dirty, deadly–and banned”), while actively suppressing research that challenged the efficacy of gun control. In fact, the situation with CDC got so bad that in 1996, Congress was forced to act, and passed the Dickey Amendment, which prohibited the CDC from using any of its funding to advocate for gun control (stupidly, the current Congress returned to prior practices, and just funded $25M for gun research that will certainly trend anti-gun).

Furthermore, the President pushed for and signed legislation that created the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS), which applied to all new firearms sales. NICS was the nation’s first mandatory federal background check and waiting period (five days, until the NICS system was fully operational).

But the Clinton assault on guns and gun owners was not complete. In an effort to place even more pressure on the industry, the President directed his Secretary for Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to muscle the major firearms manufacturers into signing agreements that would place more restrictions on firearms commerce. To entice cooperation, HUD Secretary Andrew Cuomo (the same Cuomo who, as Governor, would later use extra-legal measures to force the unconstitutional “SAFE Act” through the New York legislature in an after-hours, “emergency” session in January 2013) arranged for several municipalities to drop their product-liability lawsuits against firearms manufacturers who participated in the agreement. Although the municipalities stood little chance of winning the frivolous suits, they knew that mounting a defense would be prohibitively costly for the small firearms companies they brought to court with taxpayer money. The suits were simply designed to cripple the firearms industry through litigation, so Cuomo’s promise of relief was a compelling offer.

The rest of the industry–most notably, arch-rivals Beretta and Glock–rejected the effort, but British-owned Smith & Wesson agreed, in exchange for: Promises of favorable treatment on municipal (at least fifteen cities signed, including Atlanta, Detroit, Los Angeles, Miami, St. Louis, and San Francisco), state, and federal firearms contracts; The promise that they would not be sued by the Attorneys General of New York and Connecticut, and; Being dropped as a defendant in many of the 30 existing municipal lawsuits.

The “HUD Agreement” was signed on March 17, 2000 between Smith & Wesson and the Departments of the Treasury and Housing and Urban Development. The terms of the agreement were both oppressive and extensive, requiring changes in technology, handgun “safety” features, product testing, sales and distribution agreements, records reporting to BATFE, advertising, and consumer purchase restrictions. The agreement mandated investment in “smart gun” technology, prohibited S&W from manufacturing new designs that could accommodate grandfathered magazines (under the new Clinton ban) that held more than 10 rounds, pressured dealers to share more of their sales records with BATFE than the law required, mandated magazine disconnects and loaded chamber indicators, mandated a dealers “Code of Conduct” that required (in part) background checks on every transaction (even when not required by law), mandated a prohibition on persons under 18 in gun stores without an adult being present, and limited handgun sales to one every two weeks, among a long list of other requirements.

The agreement also required an internal locking device on all guns sold by Smith & Wesson within 24 months.

Public Reaction

The gun community’s reaction to the S&W-HUD agreement was swift. Smith & Wesson came under immediate criticism from Second Amendment supporters across the nation, particularly after information surfaced indicating they had betrayed their fellow industry partners by sharing confidential communications from industry meetings with the feds during negotiations.

Many Smith & Wesson dealers dropped the brand, refusing to abide by the highly restrictive and intrusive “Code of Conduct” that Smith & Wesson now required of their dealers. Business dropped off as the distribution network for Smith & Wesson products dried up.

Revenue had been falling for years before the HUD agreement, but Smith & Wesson took an even larger hit in the aftermath. Many enthusiasts (the biggest spenders in the market) boycotted the brand, and sales suffered. Additionally, the promised and highly-anticipated municipal, state and federal contracts never materialized. The HUD Agreement, designed to save Smith & Wesson from bankruptcy, was instead killing revenue.

However, the low point hadn’t been reached yet. The majority of the gun buying public–then and now—didn’t stay abreast of political developments that affected their firearms rights, and their first opportunity to vote with their wallet wouldn’t come until a year later, with the introduction of the HUD-required internal locking devices.

The Lock

In May of 2001, just over a year after the HUD agreement was signed, ownership of Smith & Wesson changed again, with Tomkins plc selling the brand to Saf-T-Hammer Corporation. Saf-T-Hammer was a manufacturer of firearms locks and safety products, and by the end of the year, an internal locking system of their design had begun to populate the left sideplates of Smith & Wesson revolvers, in accordance with the terms of the HUD Agreement.

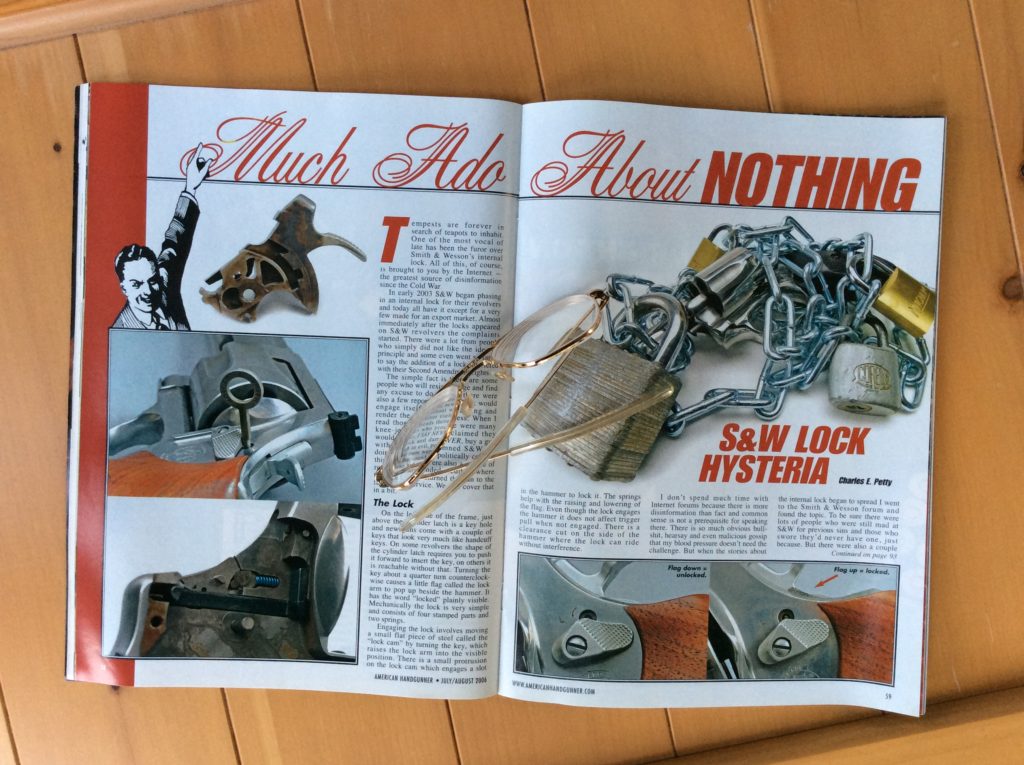

The lock is a key-operated system that blocks the movement of the hammer when activated. When the key is inserted into the lock and turned counterclockwise, it rotates a cam on the inside of the sideplate. This cam bears upon a rotating locking piece that has a raised stud on its surface, and when the cam rotates, it rotates the locking piece and raises the stud into position.

In the raised position, the stud fits into a notch that’s recessed in the left side of the hammer, which blocks the hammer from moving rearward. The trigger will not move to the rear when the lock is engaged, because the hammer has been fixed in position by the stud on the locking piece, and the rest of the action is now tied up as a result of the immovable hammer. The cylinder may be opened or closed with the lock engaged, however.

On a locked gun, when the key is turned in a clockwise manner, the cam rotates the locking piece again, and the stud leaves the notch on the hammer, freeing it for travel. In the unlocked position, the stud rides in a curved channel in the side of the hammer, where it doesn’t interfere with hammer travel.

On exposed-hammer revolvers, the locking piece is partially raised through a gap in the frame’s hammer channel when it’s rotated to the locked position. The exposed part of the piece looks like a small flag, and it bears a “LOCKED” inscription on it as a visual reminder that the system is . . . well, locked. On “hammerless” revolvers, there is no visible locking flag when the lock is engaged, but the system works identically on the inside.

Reactions

When the locks first started to appear on guns in 2001, the reaction was generally negative. Perhaps it is more accurate to say that the customers who disapproved of the lock were more vocal than the ones who liked it. Some consumers certainly appreciated the ability to lock up the mechanism of the handgun as a security feature, but the overwhelming majority of people who expressed an opinion about the lock absolutely hated it . . . and they were loud.

From the very beginning, there were three main reasons why shooters hated the lock. The reasons have stayed the same for the better part of two decades now, even as a new generation of shooters has entered the culture. The three reasons, in no particular order, are Cosmetics, Reliability, and Symbolism, and we’ll take a look at each.

Fugly

First, cosmetics. The simple fact is that there’s a lot of people who hate the lock because they think it’s ugly. Beauty really is in the eye of the beholder, so there’s probably some people out there who don’t mind seeing the lock hole and its direction arrow on the sideplate, but there’s also a legion of folks out there who think it looks awful. Neither side is wrong, they just have different aesthetic tastes.

Personally, I happen to fall in the latter camp. I think the lock looks like a turd starting to crown in the sideplate of the gun, with an arrow to show you which way to wipe. But that’s just me. As we used to say on the web forums, back in the pre-dawn era before social media ruined communication, YMMV.

Red Flags

It didn’t take long before reports of lock failures (more precisely, undesired self-engagements of the lock) started creeping up on Al Gore’s internet with frequency, casting doubt on the reliability of the lock.

Looking back on it now, while many of the early lock failure reports were spurious (for a while there, shooters were quick to label any revolver malfunction as a lock issue, even when there was no evidence to suggest a link), there was a real fire to go with all that smoke. While Smith & Wesson and some influential personalities in the gun press were quick to dismiss the first reports of self-engaging locks, enough data points were accumulated over time to indicate that the lock was indeed malfunctioning under certain conditions, and binding the action so that the trigger and hammer were frozen in place.

While there have been credible reports of malfunctions with both exposed hammer and hammerless designs, a variety of calibers, and frames made from all the various materials (steel, aluminum, Scandium), a fairly consistent pattern has emerged in the majority of confirmed lock failures. In general, the guns most susceptible to self-engagements have been exposed hammer guns, with frames made of lightweight materials (particularly Scandium), firing large caliber rounds (.44 Magnum, in particular) or high pressure, smaller caliber rounds (such as .357 Magnum or .38 Special +P+).

In practice, the locking piece (that doubles as a “LOCKED” flag on the exposed hammer guns) is under very minor spring tension, from a small coil spring at its base. Under the severe forces of recoil in lightweight, heavily-charged guns, inertia has allowed the locking piece to “float up” into a raised position and bind on the hammer, locking it in place. Sometimes this malfunction can be cleared in the field, but other times the jam has been severe enough that it required disassembly of the revolver and/or the attention of a trained gunsmith.

Because the locking piece is bigger on the exposed hammer guns, to incorporate the visible flag, there seems to be a greater tendency for these guns to jam up than on the hammerless models, where the locking piece is smaller and has less inertia to overcome the coil spring tension.

The crowd of shooters who were predisposed to dislike the lock seized on the reports of self-engagements and declared lock-equipped guns completely unsuitable for defensive use, or for protection from dangerous game. In hyperbolic fashion, a legion of Keyboard Commandos preached dark visions of gloom about shooters who would wind up “dead in the streets” with self-engaged, locked guns in their hands.

In truth, the likelihood of a lock self-engaging was low for the vast majority of guns and shooters. The problem was real, and the risk was not to be ignored or dismissed, but the vast majority of gun-ammo combinations were unlikely to cause the lock to self-engage. Choosing a self defense gun that was not equipped with an internal lock was a reasonably conservative way to avoid a potential problem, and one that many experts suggested, but the people who were stuck with a lock-equipped gun (due to product availability or state laws) weren’t doomed to suffer a life-ending failure—particularly if they weren’t shooting a Scandium-framed, .44 Magnum or .357 Magnum with heavy loads.

My personal view is that I would prefer a gun that is not equipped with an internal lock for self defense missions, but if circumstances dictate a lock-equipped gun as the best–or only–choice, I wouldn’t fret too much. Instead, I would just focus on frequent training with my gun under realistic conditions (using duty ammunition, or an appropriate analog) and keep an eye out for any indications of trouble.

If your lock-equipped gun has a track record of running smoothly with duty-level ammunition, then you can be as confident in it as you would any other gun (keeping in mind that guns—even guns without locks—can break, right?). If problems actually do arise with the lock during training, I’d replace the gun with a different type if I could, or if I was stuck with the gun, I’d start experimenting with other types of ammunition, to find a load that’s problem free after rigorous testing.

As for hunting dangerous game with the lightweight Magnums, I think I’d avoid it entirely and just choose a steel-framed gun in the same caliber, putting up with the extra weight for recoil control and the added guarantee of reliability. I’m sure my wrists and my orthopedic surgeon would appreciate my choice, too.

Politics and Religion

The last of the major beefs about the lock is the one that I personally think is most important, and is also the one that has had the greatest influence on the continued opposition to these guns.

For many of us RevolverGuys, the lock has symbolic value. Yeah it’s ugly, but the ugliness of the lock transcends what the eye can see. When we see the lock, we see a reminder of the powerful, anti-liberty, anti-gun forces that colluded to deprive us of our civil rights in the Clinton era. We also see a reminder of one of their most important victories—a signed agreement that turned one of the most prized and beloved of American companies against its own customers, against its industry brothers, and against the Constitution itself.

The lock reminds us of all the losses we’ve sustained to those enemy forces, and the ongoing struggle to prevent our Constitutionally-recognized, natural rights from being infringed. It sticks in our craw like an enemy flag being flown over an American position, and stings like a finger poke in the eye from a bully.

There’s a lot of Second Amendment supporters today who aren’t old enough to remember the HUD Agreement and Clinton’s war on guns, but all of them understand the clear symbolic connection between the lock and the anti-liberty forces arrayed against us today, who would deprive us of our natural right to keep and bear arms in defense of self and others.

We hate the damned lock because we hate the elitist, deceitful, malicious, nanny-state, anti-gun movement that foisted it on us. And that’s never going to change.

Looking Back

The 2000 HUD Agreement was signed by a British-controlled Smith & Wesson. The same Brits who marched on Lexington and Concord to seize our powder and arms at the birth of our nation, showed little regard for protecting the rights of American citizens to keep and bear arms some 225 years later when they shook hands with the American traitor, Secretary Cuomo.

A year later, Smith & Wesson was sold to an American corporation (who voluntarily—and regretfully—complied with some key terms of the agreement, despite the fact that the newly-elected Bush Administration advised that the federal government would no longer bind them to the Clinton-era agreement), and it remains in American control to the present day. This is important, because it’s a key element in the full recovery of Smith & Wesson to its former status as an American icon.

While there’s many people out there who doubt that Smith & Wesson will ever fully renounce the legacy of the 2000 HUD Agreement by removing the locks from their guns, the history of our industry hints otherwise.

After Winchester made changes to production methods and popular firearms designs in 1964 to save money, there was a huge outcry and backlash from the buying public. Sales plummeted and demand for “Pre-64” models of the most popular Winchester rifles spiraled upwards for decades, as influential members of the gun press continued to rail against impressed checkering, stamped trigger guards and floor plates, push feed actions, inelegant looking stocks, and lower standards of quality.

It took 28 years for Winchester to come to its senses, and redesign its Model 70 to give the customer what they wanted all along. By that time, production quality had slipped to the point that the newly-redesigned guns didn’t measure up to the older standards, but within a few years, new ownership and licensing agreements returned the quality to the Winchester mark, and the “Rifleman’s Rifle” was worthy of the “Horse and Rider” logo again.

A similar rejuvenation of the classic 1911 pistol occurred in the wake of Colt’s decision to change the firing pin lockwork to the Series 80 standard in 1983. The buying public was mostly cold towards the new firing pin block, but enthusiasts were particularly unhappy with the block’s effect on the trigger pull, and were exceptionally vocal in their opposition to the change. They, and influential members of the press and industry, complained enough about the change that several of Colt’s competitors began to market their no-block lockwork as a premium feature, and consumers responded.

As a result of the discontent and the lost revenue, Colt’s announced several decades later that it would return the pre-Series 80 system (nominally called the Series 70 system, although that’s not an entirely accurate label) to production, offering its consumers the choice between a Series 80 gun with the firing pin block, or a Series 70 gun with a heavier spring and lighter firing pin to achieve a comparable level of safety.

Looking Ahead

In the Winchester and Colt’s examples, we see an indication of what may lie ahead for Smith & Wesson.

Naysayers will point out that the lock is viewed as a “safety feature,” and as such, Smith & Wesson could never back away from the design without a significant legal and/or public relations issue. They believe that removing the lock would subject Smith & Wesson to claims that they were “making the guns less safe,” and the associated liability.

It’s important to note, however, that Smith & Wesson never fully abandoned the no-lock guns. Shortly after the lock became a heated issue, Smith & Wesson made a run of Airweight revolvers using old, pre-lock frames that were in inventory. This limited run of guns sold so well that Smith & Wesson continued to offer a limited supply of no-lock, J-Frame revolvers, through the present (often marketing the absence of a lock as a premium feature, reserved for more expensive models).

If the argument that an internal lock was an essential safety feature was compelling, then these no-lock guns would have disappeared entirely decades ago. Liability concerns would have required it. The fact that they have not, is an indicator that Smith & Wesson and their attorneys understand that while the locks can be viewed as an added “security feature,” they are not required by federal law, are not an essential “safety feature,” and the guns are not unsafe without them.

In practical terms, there is little to keep Smith & Wesson from expanding the existing line of no-lock SKUs, and offering their consumers a more comprehensive choice between lock and no-lock versions, much as Colt’s offers their customers a choice between Series 70 and Series 80 firing pin safety systems. Actually, a more powerful analogy might be in front of Smith & Wesson’s own nose, as they sell multiple variants of their semiautomatic pistols, some with added “safety features” (loaded chamber indicators, magazine disconnects, external safety levers), and some without.

There are important economic reasons for Smith & Wesson to consider this course. At the time of the 2000 HUD Agreement, Colt’s had left the commercial market entirely, and Smith & Wesson’s only true competition in the revolver market came from Ruger (which had a limited selection of double action revolver designs), and to a lesser degree, Taurus (which was perceived as a lesser-quality product at the time). Smith & Wesson may have reasoned that consumers would continue to buy their product, even with an internal lock, because there were so few viable alternatives.

The market has changed significantly since then. Colt’s is back in the revolver business in a big way, and Ruger has become the 600 pound gorilla in the industry, with an extensive selection of high quality products, including designs like the LCR that improve on every aspect of the compact revolver (including sights, trigger and ergonomics), and the SP101 and GP100, which set the standards for performance in their size and weight classes. Even Taurus has stepped up their game, with a new plant in Bainbridge, Georgia, and a vision to grow the company into a leading competitor.

There’s also the new kid on the block, Kimber. The “1911 guys” have managed to build an exciting and compelling revolver, and it’s targeted at the cognoscenti in the revolver market, who appreciate a premium product. The Kimber K6s improves on the basic Smith & Wesson offering by delivering an improved trigger, improved sights, and an additional round in the chamber, while remaining remarkably close in size to the premiere J-Frame, the Model 640.

Oh . . . and it doesn’t have an ugly internal lock hole in the sideplate.

Back to the Future?

So, the game has changed, and Smith & Wesson can no longer rely upon their market dominance to overcome the softening demand for their lock-equipped revolvers. Just as Winchester had to rethink their Post-64 strategy in the wake of growing competition from Savage, Ruger and Kimber, Smith & Wesson may soon have to reexamine the calculus that has them sticking with an unpopular arrangement that a former owner saddled them with, during an economic and political crisis.

Indeed, the November 2019 announcement from American Outdoor Brands (AOB—the Freedom Group-type conglomerate that combined Smith & Wesson, Thompson Center Arms, Crimson Trace, and 13 other outdoor product brands), that they will separate the Smith & Wesson brand from the rest, may accelerate this. In a politically-charged marketplace—where gun manufacturers are constantly under attack from investors, a weaponized banking industry, radical shareholders, ignorant politicians, and foolish citizens— it appears that AOB is trying to insulate their outdoor products businesses from the more contentious firearms manufacturing components. The new Smith & Wesson Brands will have to find its own way in a difficult marketplace that is still suffering from softened consumer demand (the “Trump Slump” continues to hurt many companies in the industry), and a rejuvenated, no-lock revolver line could be a key component of establishing a solid foundation for the newly-independent company.

Today’s Smith & Wesson has the designs, the engineering, the creativity, and the quality control they need to do something really special here. Let’s hope that the Smith & Wesson leadership team also has the vision and courage to seize the opportunity, increase their revenue in a down market, and fully restore the market’s faith in the brand as a steward of the Second Amendment.

I’ll be the first in line with my credit card, when they do. I would probably have another dozen Smiths in the safe, were it not for the lock, and I’d like to give them my money. The lock is a deal-killer for me, though, and I know I’m not alone. There’s a lot of pent-up demand for no-lock S&Ws out there amongst the enthusiasts who spend the most money on firearms.

We need a strong and vibrant Smith & Wesson in the market—they’re an American icon that I want to see flourish. I just think it’s time for them to break free of the chains from a dark past which are holding them back.

Can you hear us, Springfield?

*****

References:

Kopel, Dave. “Smith & Wesson’s Faustian Bargain, Part I + II.” http://www.davekopel.com/NRO/2000/Smith-and-Wesson’s-Faustian-Bargain.htm

Supica, Jim & Nahas, Richard. Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson, Gun Digest Books, 2006;

Funding Universe, “Smith & Wesson Corporation History.” http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/smith-wesson-corporate-history/

Handloader Magazine. “Smith & Wesson,” linked at Gun Owners of America, https://www.gunowners.org/op0123htm.htm

HUD Archives. “HUD Prefers Gun Purchases From Companies Adhering To Code of Conduct, Calls On Mayors To Unite In Preference For The Companies.” https://archives.hud.gov/news/2000/pr00-57.html

HUD Archives. “Agreement Between Smith & Wesson and the Departments of the Treasury and Housing and Urban Development, Local Governments and States.” https://archives.hud.gov/news/2000/gun agree.html

NRA Institute for Legislative Action. “Beretta Statement On the Smith and Wesson Agreement.” https://www.nraila.org/articles/20000905/beretta-statement-on-the-sw-agreement

NRA Institute for Legislative Action. “The Smith & Wesson Sellout.” https://www.nraila.org/articles/20000320/the-smith-wesson-sellout

Interesting. Thanks for the write up.

Very insightful article Mr. Rosenfeld, it addressed my questions in spades. I happen to love Smith revolvers and have a small collection of them : all are pre-lock, with spike hammers. I must admit, I have owned a few Smiths with the lock on the side plate but they bothered me and weren’t kept very long. In fact, I’ve had serious lock up issues with two Smith 22s only maybe three years ago and Smith would not fix them because – they said they were bought at a dealer and not directly from them.

I will never buy a Smith again of ANY vintage. Both guns would stop working after firing maybe eight to ten shots ; then after they cooled, they would start working again.

Thanks for a great article,

Wayne Odle

I think something got lost in the translation, Wayne, since S&W doesn’t sell firearms directly to their customers. They’re all sold through dealers. Perhaps there was an issue with warranty service being honored on a used gun. In any event, I’m sorry you had the problems. The little S&W 43C in .22 LR has developed a reputation for problems, and I wonder if those were the guns giving you fits?

43c has no lock… they have had major issues although mine has about 4k on it without issue.

I was on the fence. No more. No internal locks for me. I was going to by a 686 today but it looks like time to start a Ruger search. It’s hard to give money to a company that’s working hard to become extinct.

Chuck, S&W just announced a No-Lock 686 Mountain Gun as a Lipsey’s Exclusive. You’ll find it on Lipsey’s (look on the Exclusives page) or S&W’s (look on the SMU & Spec, then SMU / Bundle page) websites.

S&W also released three No-Lock Classics at the 2025 SHOT Show (see our coverage). They’ve come to their senses and they’re leaving the lock behind.

I own ten revolvers, 7 of them are Smith’s. Of those 7 only 2 are modern and have the internal lock. My internal lock guns are an 8″ 460 magnum (for obvious reasons) and a 5″ 686 plus performance center. The 686 is by far my least favorite revolver The internal lock is crap. It does not feel like it clicks in the locked or unlocked position. Not to mention the fit and finish is vey poor. I sent it back to Smith and Wesson because there were burrs on the recoil plate that caught on 357 cases hindering the rotation of the cylinder. What I got back was a revolver with burn marks all over the cylinder from firing and a note that they replaced some of the internals. The burrs were still on the recoil plate. I am a die hard Smith fan and I fully intend to buy more Smith’s in the future. I still need a couple J frames (round and square butts). I would also like a 44 mag with a long barrel. But,(in the voice of Queen Amidala) It is clear to me now that Smith and Wesson no longer functions. I pray they bring sanity and compassion back to Smith and Wesson. Until then, I will buy pre-lock Smith’s! Thank you for your very informative piece.

It was not mentioned in the article, however… I was told by a very good gunsmith that the ILS negatively affects the overall action of S&W revolvers to the extent that a seasoned shooter can feel the difference in both double and single action shooting. In short, he told me that the ILS negatively affects the feel of the action.

I totally agree that Smith and Wesson should never have added the cylinder lock.

I have a 629 with the lock and I am sorry that I agreed to trade an older model 29 for it. I agreed to make the trade before examining the 629 and wish I had backed out of the deal. I still own a couple older Smith and Wesson revolvers without the locks. Even though I would love to buy an eight shot model 627. I refuse to because I dislike the look of the cylinder lock. I hope Smith and Wesson will reconsider and begin manufacturing all of their revolvers without the lock in the near future. I love the look and quality of a Smith but I refuse to buy another one with the cylinder lock.

Honestly one of the best treatments of this subject I’ve ever read. This is a masterpiece.

I’m a revolver guy, always have been. And I’m a Smith and Wesson guy, always have been. I own many. I would buy a model 60, 66, and/or 360 PD TODAY if it didn’t have that internal lock. NONE, let me repeat that, NONE of my revolvers have this lock and they never will. I will never change my mind. I’m ready to put my money where my mouth is TODAY. I would easily spend $3k on some new revolvers TODAY if that lock was gone.

Come on Smith & Wesson! Show me, a total S&W lackey, that you put me first. I’ll do the same as I always have for you. Let’s put this scar behind us together.

Agreed, Scott! It’s time for the lock to go. Fortunately, I think we’re seeing the first crack in the dam with the new Ultimate Carry J-Frame revolvers from Lipsey’s and S&W. NONE of them have a lock! Let’s hope this starts a new trend.

I’ve never owned a firearm with an internal lock and I never will, but if I ended up with one it’s easy to disassemble, grind off the offending tab and carry on.

If you’re satisfied with that, carry on. For many of us, it’s unacceptable.

Thank-You Mike for writing a well researched article on my favorite revolvers.

Always good to know the background, and the “why”.

Absolutely, Joe. There’s a lot of forgotten history here, that’s important to preserve and undertand.

The vast majority of S&W’s own staff doesn’t remember or understand it, because it all happened before they got there . . . in most cases, before they were even born. We recently had a key figure there express that he didn’t understand, “why the lock is such a big deal?” Obviously, he doesn’t read RevolverGuy.

We’ve turned an important corner, though. We now have the ear and support of decision makers at the company, and they are motivated to correct the errors of the past. The launch of the No-Lock Classics (Models 10, 19, 36) this week is evidence of a new understanding at S&W, and I know they’re working on additional No-Lock models. I won’t be bold enough to say the lock is going away anytime soon, but we should definitely be seeing an increasing number of No-Lock products.

Finally!

I firmly agree with the author’s assessment regarding the Internal Locking System on S&W revolvers, I know Federal mandates had much to do with this decision. But, like the author, I too haven’t purchased a “pre-lock” S&W pistol since the locks became mandatory. I am elated that S&W will be releasing 3 new pistols without the locking feature, I will be purchasing the new Model 19 Combat Magnum when they are available! Kudos to whoever decided to remove the ILS feature from these 3 handguns, hopefully more will follow!

Very good story on a clusterf$&k!

I did the first “documented” story on an S&W lock failure from a “credible” source on the Michael Bane Blog way back in 2007:

http://michaelbane.blogspot.com/2007/08/s-revolver-safety-failure.html

Was a shitstorm, to be sure. I talked to Charlie Petty, who was a good friend of mine, and he asked me whether the event was “repeatable.” I said I had duplicated the results and had them on video. My take was hotter — especially heavy-for-bore bullets — in Scandium frames bounced the lock.

I subsequently removed the locks from 2 of my working revolvers, including a snub and an N-Frame .44 Special.

Michael B

Thank you Michael! Fortunately, I think S&W is starting to wake up from this long nightmare, and the future I spoke about is happening now. I surely won’t be sad to see non-lock SKUs replacing the retarded ones.

Best article I have ever read on the subject. Now, in addition to the four J-UC models, it looks like there are six other new models without locks–the Classic 36, 10, and 19 and I saw the release about the 332 UC Ti, 686 Mountain Gun, and 629 Mountain Gun. I just wish these were all standard production guns you could just walk into a gun store and buy, as opposed to having to special order.

Thanks!

Paul B.

Paul, we’ve had some involvement in those projects behind the scenes, and I was happy to see them at SHOT this week. All I can say is things are heading the right way, and I think you’ll see some positive changes in the main catalog as we move ahead. These special projects will pave the way for improvements across the board, over time.

Very glad to see things moving in this direction. I am old enough to remember all the mess with the HUD lawsuits. Thank you for all of your efforts sir!

Paul B.

Amazing research! Thank you sir

Thanks for the article! I don’t like the looks of the lock, glad that S&W is making more revolvers without it.

I think I have you to thank for my recent acquisition of a Manurhin MR88;

thanks for the heads up!

Glad you enjoyed the article, John. We’re THRILLED to see the lock making its exit.

Also glad you were able to act on the MR88 tip in our 2025 SHOT Show coverage! Send a comment to that article and let us know what you think of the “French Ruger” please!

I was wondering about “The Lock”, as I saw no lock and lock pistols on S&W’s site when looking at rarely viewed by me wheel guns. I’m typically an old 1911 guy, but am reasonably agnostic for self-defense weapons, they’ll all poke holes and I’m proficient with pretty much all small arms.

Your article attracted my attention by including mechanical views of the device.

Now, I am an old rangemaster, so safety is supremely big with me, as anyone that I’ve bum’s rushed off of a range can attest to. Safety third, safety second and safety first, because firearms are dangerous if improperly handled and to a modest degree, even when properly handled if improperly maintained or of poor quality (remember the self-dismantling RG “Saturday Night Specials”?).

So, an additional safety isn’t unwelcome, it’s something to train to operate under stress. This being a bit of safety, a bit of weapon security. Judging from the story, there were some teething problems with hot loads, which well, comes with new weapons and weapon systems, served over 28 years in the Army, so I’m intimately familiar with those. Ideally, one waits for the A2 model or higher, if possible, the original no letter and number being rather deficient…

Some parts, I suspected initially and the story confirmed, a weakish spring, a massive component and a hot load leading to inertial displacement under heavy recoil. Well, most users aren’t taking their wheel gun out during Buick season, so that’s not a consideration from my seat. If I felt such a need, I’ll load the last round with Atomic Annie and have it to claim that bull Buick if necessary. I doubt I’ll be headed out on the one day of Buick season, since they’re near-endangered these days.

Still, I do kind of miss my old 686 and will probably save some pennies to get a replacement of that pistol.

And the rest, like Ma Deuce’s infernal detent spring, is a PMCS issue.

And I recycled a squad of infantry back to my M2 class, when they launched their barrel 25 meters, as I spent ten minutes on that damned detent spring and they missed that on their gun, which got deadlined.

I bugged their replacement gun after they retook my class and they passed that one.

Never irritate one’s rangemaster/instructor/SF medic that’s giving you a class on a crew served weapon by ignoring a safety lesson that was nagged on, I had a reason to and it got illustrated in a way that endangered the safety of that crew.

Yeah, their medic was giving a weapons class, wasn’t the first or last. Also gave mortar classes and TOW missile classes, where I outgunned every student, to my shame as an instructor. But then, the only man in my unit that outshot me was our senior sniper and he took me in a all weapons unofficial competition by one to two points and we both learned new things each time.

We’re BIG on safety here at RevolverGuy too, Steve, but the internal lock was never a plus in the safety column, in my opinion. An owner who relied upon the internal lock to prevent unauthorized access of a loaded gun was making a gamble of the worst sort. In an emergency, the gun would be very difficult to “activate,” and one can easily imagine the Rule 2 violations that would ensue, as they tried to unlock it under duress. This, of course, assumes you can even find the key to begin with (and based on the number of lost keys I’ve seen reported, it’s not a good assumption). In my opinion, it’s far better to get a proper lock box to prevent unauthorized access, yet still preserve reasonably fast access for an emergency. That would also help to reduce the chance of staring down the barrel of your own gun, when you unknowingly interrupt a burglary in progress at your home.

I just noticed on the S&W website they are also now releasing the model 19 Carry Comp without the lock. The finish of the gun however is what S&W is calling moss, not blued and it doesn’t look flattering. Why oh why did Smith do that? Ugh.