I admit it. I’m a gun nut. It doesn’t matter if they revolve or cycle, or if they load from the front, the back, or the bottom. It doesn’t matter if they hold a single cartridge or half a box full. It doesn’t matter if they’re made of blue steel and wood, or Tenifered steel and plastic. If they go “bang,” I love them.

So, when the Shooting, Hunting and Outdoor Trade Show (SHOT Show) rolls around every January, I feel like I’m getting a second shot at Christmas. As the show nears, the anticipation builds as I think of all the wonderful guns and people that I’ll be able to see, and just like the kid who dreams about the unknown possibilities that wait for him under the tree, my mind becomes preoccupied with thoughts of the exciting new products that will be unveiled at the show.

You can imagine my delight then, when Kimber introduced the K6s revolver to the shooting world at SHOT Show 2016. Not only was the gun tailor fit for a RevolverGuy, but it also came as an incredible, and highly unexpected, surprise.

This is the story of the development of this impressive revolver.

Little Package, Big Surprise

As 2016 dawned, the snubby revolver market had grown stale in many ways. Ruger had upset the market with its unique, polymer-steel-aluminum hybrid LCR revolver a few years before, but aside from that notable highlight, things had been pretty boring in the snubby world since the rollout of the new Centennial frame by Smith & Wesson in 1990. With the LCR’s big splash behind us, it looked like the snubby market was settling down and going back on cruise control for the foreseeable future. Kimber had other plans, though.

Now, if you had asked a crowd of RevolverGuys where the next new revolver design would come from, Kimber probably wouldn’t have made the list. Since their rebirth in the mid-90s, they had firmly established themselves as 1911 pistol and (going back to their roots) bolt action rifle manufacturers. A new hunting rifle or mini 1911 wouldn’t have caused a stir, but a revolver? That was an honest-to-goodness surprise.

Even better, Kimber’s new gun, the K6s, thumbed it’s nose at the snubby status quo and gave the market something it had been pining for since the demise of the once great, rampant Colt—a six round cylinder! It was immediately clear that Kimber wasn’t messing around, and a legion of gun guys—even the bottom-feeding heathens who had never been interested in revolvers—were suddenly excited about Kimber’s new design.

From Whence It Came

The K6s didn’t appear out of thin air, of course. A lot of energetic and talented people worked hard on the design prior to its release at SHOT 2016.

The K6s began in the minds of a few RevolverGuys who worked for Kimber. They were enthusiastic about producing a wheelgun with the Kimber logo on the side, but also wise enough to seek input from recognized subject matter experts outside the company.

One of those experts was Grant Cunningham, a highly regarded gunsmith who hung up his shop apron to focus on providing training and education to a rapidly growing population of self defense-minded shooters. As a specialist in the breed, Grant had a detailed knowledge of revolvers past and present, and particularly their inner workings. Furthermore, as a revolver enthusiast, and one of the few trainers out there offering revolver-specific classes, he had a unique insight to the qualities that were desirable in a defensive revolver. So, it was an excellent move for Kimber to approach him at SHOT Show and bring him aboard as a K6s consultant early in the project.

Grant made “more than one trip” to Yonkers to work with the design and engineering team responsible for K6s development, and found them highly receptive to his inputs. As a collection of RevolverGuys with a blank sheet of paper and a mandate to create the best defensive revolver possible, everyone brought their utmost to the table to make it a success.

That blank sheet of paper didn’t stay empty for very long with that much enthusiasm and experience in the room. At his first meeting with the Kimber team, Grant suggested four simple requirements for the new gun:

It had to be compact, to aid in concealment;

It had to hold six rounds;

It had to have excellent sights, and;

It had to have an excellent trigger.

The Kimber team had been thinking along similar lines, and their designers and engineers filled in the gaps. When Grant returned to Yonkers on a future visit to see the first prototype, he was immediately impressed with what he saw.

First Impressions

The new gun was definitely a Kimber. When Grant saw it for the first time, the lineage was clear. To begin with, all major components were made from stainless steel. Over the past decade or so, the industry standard had slowly shifted towards aluminum alloys, polymers, and exotic alloys made with light weight, high strength metals like Titanium or Scandium, but Kimber’s strength lay in forging and machining steel, so the K6s would follow suit.

The stainless steel format was the perfect choice for the caliber, .357 Magnum. Although the caliber hadn’t been specifically addressed in early planning, Grant admitted to being a little surprised to see the gun chambered in it, thinking instead that it would be a .38 Special. Going with the Magnum was a “Kimberesque” move though, as the company had already developed a reputation for building small powerhouses with its line of compact and subcompact 1911 pistols. The stainless construction of the K6s would help to tame the powerful cartridge, and ensure long term durability.

The lines on the gun were classic Kimber as well. Whereas snubby revolvers are typically a study in curves and rounded surfaces, the K6s looked positively angular and square. From the barrel profile, to the cylinder and frame flats, to the angular backstrap that flowed neatly into the rear sight, the gun had a look that was unmistakably Kimber. This is what a revolver made by 1911 guys looks like.

In size, the K6s compared favorably to its competition, approximating the size of its nearest competitor, the .357 Magnum Smith & Wesson Model 640. The K6s weighed the same, at 23 ounces, and was only .06” longer in overall length, and .05” wider than the 640. Despite the extra round in the cylinder, the K6s managed to be no bigger than its 5-shot rival.

The gun was built as a double action only, with no visible hammer spur. This had been the team’s direction from the start, and Grant was pleased that his personal preference for a “hammerless” design was shared. Grant knew the format had become de rigeur for concealed carry revolvers since the introduction of the improved Centennial-style frame by Smith & Wesson in 1990. All the major manufacturers had exposed-hammer designs in their catalogs for the traditionalists that couldn’t be without them, but the serious carry guns had all been hammerless (not just spurless, but closed frame “hammerless”) for over two decades at this point, and the K6s would be the same.

Interestingly, the early prototype of the K6s lacked a good “shoulder” on the backstrap, which allowed the gun to roll in the hand during recoil, particularly with the powerful Magnum ammunition. The collective team recognized the problem and changed the profile of the backstrap to include a more aggressive shoulder on later versions, above which the frame sloped upwards and blended nicely into the sights.

Ah, the sights. From the outset, the prototype had high visibility sights that gave an excellent sight picture, just as Grant had requested. The Kimber engineers designed a wide, ramped, front sight blade that was pinned to the barrel, not milled as an integral part of it. It was serrated and black, and easy to see through the generous notch of the black, serrated rear sight. The rear sight was dovetailed (a wonderful detail, offering great flexibility) into the frame in a manner that retained the sleek, no-snag lines of the gun. Legions of snubby fans who had strained for decades to see tiny slivers of front sights through shallow notches milled into the topstrap of their guns would instantly rejoice when they sighted in the K6s for the first time.

The gun would evolve and be optimized during the design phase, but the core essentials were there from the very start. From the moment he saw the first prototype, Grant knew it would become something special.

Locking Details

There are many choices that a design team needs to make when it creates a new firearm, and some of them have a great influence on other aspects of the design.

Take cylinder lockup, for instance. At present, there are three popular methods for locking up the cylinder of a double-action, swing out cylinder revolver. We’ll simplify things by calling them the Colt’s, Ruger, and Smith & Wesson methods, since each of these companies have typically used a different approach.

In the Colt’s method, the cylinder is locked at the rear only, with the tip of the spring-loaded cylinder release going into a recess in the ejector. There is no lockup on either the crane, or the forward tip of the ejector rod.

In the Ruger method, the cylinder is locked at the rear in a similar fashion, with the center pin lock going into a hole in the frame. However, there is also a spring-loaded latch on the crane that locks into the frame, which secures the front of the cylinder. Those of you who are students of gun history may recognize this feature from the vaunted Smith & Wesson “Triple Lock” (or .44 Hand Ejector First Model, or New Century—pick your favorite label). We’ll just call it the Ruger method for now, since they’re still using it as their primary method. Smith & Wesson has mostly abandoned it (we say, “mostly,” because the ball detent used in the X-Frame and the new “Combat Magnum” frames has some similarities).

The last method is the Smith & Wesson method, which locks the rear of the cylinder the same way, but also locks the front by means of a spring-loaded locking bolt that bears on the forward tip of the ejector rod. There is no locking mechanism on the yoke in this design.

Since they started with a clean sheet of paper, the Kimber team could have chosen any of the three methods. If they had gone with the Colt’s method, they would have needed to make the hand turn the cylinder clockwise, to help ensure the cylinder would stay aligned during recoil. It helps to turn the cylinder into the gun for added support when it’s only locked up at the rear, so the bolt locks the cylinder in place after the hand spins it clockwise into position.

The Colt’s method could have worked, but the .357 Magnum is a powerful cartridge for such a small frame, and the Kimber team was rightfully concerned about making sure the K6s cylinder was supported on both ends, so it was decided that they would choose another method.

The Ruger method actually provides the greatest support for the cylinder, with its frame locking lug, but the design is more complicated and expensive to manufacture (Ruger’s use of investment casting simplifies the process, and makes it less expensive than if the parts had to be forged and machined, as Kimber would do). Additionally, there is a possibility that debris can get into the front locking mechanism and prevent the cylinder from closing or locking up. Lastly, the design forces the frame to be a little wider, and the Kimber team was sensitive to keeping the gun trim.

So, the Smith & Wesson method would be used, with the ejector rod getting locked up on either end. This allowed Kimber to use a counter-clockwise rotation of the cylinder, but it also required them to ensure that the ejector rod would not unscrew and tie up the gun, which is a relatively common problem with the design. To prevent this, Kimber wisely used thread locking compound on the ejector rod threads, to prevent it from unscrewing.

The Smith & Wesson method also puts a premium on protecting the ejector rod from getting bent. Since the Colt’s system has no locking bolt up front, it’s a little more resistant to the effect of a bent ejector rod, and the Ruger is as well, because the ejector rod is offset, and doesn’t spin with the cylinder. In the Smith & Wesson locking system though, a small bend in the rotating ejector rod can prevent cylinder rotation, as the locking bolt binds on the tip of the ejector rod. As a result, an ejector rod shroud made sense as part of the barrel profile. Kimber could have used an exposed rod and a lug, as Smith & Wesson had been doing for almost three-quarters of a century on its J-frames, but the full shroud offered more protection and also gave the barrel a beefier look. The shroud has flats and angles that help to give the K6s a distinctive Kimber look.

Action Details

Kimber had other choices to make inside when it came to the action. There was never a serious consideration of using a leaf spring to power the action, because coil springs are easier to work with (especially in a gun this size) and less expensive to manufacture, but the sear required a look.

In designs like the Colt’s revolvers, there is one continuous sear surface for double action mode, and a separate sear surface for single action mode. The effect of the continuous double action sear surface is to create a trigger pull that “stacks,” or continuously increases in weight of pull, as the trigger travels to the rear. Imagine a graph that plots trigger pull weight on the vertical (“Y”) axis, versus trigger travel on the horizontal (“X”) axis. A trigger that stacks will create an arc that starts at the origin, and gently curves upwards for a bit before it climbs sharply towards the vertical, at the end. While you can achieve an excellent trigger pull on such a design, the average shooter seems to prefer a trigger that doesn’t stack.

The alternative is to design a hammer with two double action sear surfaces, such as that found on Smith & Wesson revolvers. In this kind of design, the first three-quarters or so of the trigger pull happens on the first of the sear surfaces, and then you transition to the second sear surface for the remainder of the pull. On designs of this type, there is less stacking. In fact, on a typical Smith & Wesson J-Frame, the pull weight steadily increases to a peak on the first sear, and drops off rather quickly in the last part of trigger travel, just before the hammer is released off the second sear (those of you who “stage” your Smith & Wessons in double action understand). Imagine our weight-travel graph looking like a cane, with a linear increase in pull weight until the sharp downward curve at the end.

The Kimber team didn’t want their trigger to stack, but they also didn’t want their trigger pull weight to peak as high as a J-Frame, then fall off. They wanted a more linear trigger, with a pull weight that stayed more consistent throughout the trigger’s travel—more like the first part of the Smith & Wesson graph, prior to the drop off, but shallower.

They achieved it on the K6s with some changes to the geometry of the sear, hammer, and hammer strut. The K6s trigger is more linear than others in this class of guns. Pull weight builds slower and doesn’t peak as high. It’s a smooth pull of about 9.5 to 10.5 pounds that shooters typically report as feeling lighter.

More Touches

The Kimber team gave special attention to many other areas of the gun, as well.

From the very first prototype, the trigger face was rounded and smooth, without grooves. This allows the trigger finger to roll across the face as the trigger travels to the rear, instead of dragging on the trigger and pulling the gun off target. Grooves were popular on wide target triggers back when single action fire was the norm, but on a double action trigger, you need a smooth, narrow surface for best efficiency, and that’s what Kimber chose for the K6s.

The choice of cylinder release was another area for the team to optimize the design. The traditional Colt’s release (which is pulled to the rear) and Smith & Wesson release (which is pushed forward) were eschewed in favor of a push-button style, similar to the Ruger standard. This style of release is Grant’s favorite, and it pleased him to see that Kimber chose it, as he feels it is easiest to manipulate. It works well for either a right or left handed shooter, and even works well when the shooter is doing one-handed manipulations. Shooters with large hands will appreciate the smooth button with its protective fencing and lack of sharp edges, because the thumb knuckle won’t get cut to shreds by the latch—a frequent occurrence for this writer when shooting J-Frames, even when they’ve been dehorned.

Speaking of dehorning, the K6s is interesting in that it’s designed to look angular and square, but the gun’s surfaces are all rounded to prevent getting bit. I don’t know what kind of magic they’re using to pull it off, but the effect is both appreciated and perplexing at the same time. Grant reports this is one of the details that was good-to-go from the very start, with the first prototype.

The excellent, high-visibility, user-replaceable sights on the K6s are regulated for 158 grain .357 Magnum ammunition at a nominal distance of 15 yards. There was a time when Smith & Wesson regulated their J-Frame sights for much longer (and optimistic) ranges, and Colt’s appeared to not regulate them at all, so this kind of attention to detail will be appreciated by RevolverGuys.

The Wheel Turns

Perhaps the most interesting bit of engineering on the K6s though, is the cylinder. It was decided at the very beginning that the K6s would be a six-shooter, as God and his good friend Colonel Colt intended. The extra round may not sound like much to our self-chucker brethren, but 6 rounds of .357 Magnum or .38 Special in a J-Frame-sized gun has been the Holy Grail of snubby fans for the better part of a century. If the feat could be accomplished in the K6s, it would guarantee the gun’s success.

Once upon a time, Colt’s had made a series of highly successful 6-round snubbies, based on the Police Positive-sized D-Frame. The famous Detective Special led the pack, starting in 1927, with the aluminum-framed Cobra (introduced in 1950) and Agent (introduced in 1955) models filling other niches. By 1995, Colt’s had discontinued the old D-Frame and replaced it with the stainless SF-VI frame, with virtually identical dimensions. The SF-VI and (identical, except for markings) DS-II snubbies carried the torch for a few more years, but by 1999 both they and the short-lived Magnum Carry had been discontinued as Colt’s abandoned the commercial market to chase military contracts. Suddenly, there were no 6-shot, small frame, .357 bore snubbies in production.

That suited rival Smith & Wesson just fine. Their smaller, 5-shot, J-Frame snubbies had been top sellers for the mark since 1950, and Colt’s exit from the market guaranteed them the lion’s share of the action. Shooters bought the various J-Frame incarnations by the truckload, but many sorely missed the 6-shot Colt’s cylinders. The Smith & Wesson guns had the advantage of being smaller than the Colt’s guns, but losing that extra round was a tough price to pay for a lot of folks.

So, it was critical to the Kimber team to marry the popular 6-round cylinder without deviating much from the outer dimensions of S&W’s flagship defensive snubby, the Model 640. Could it be done?

Yes it could. The Kimber team started by offsetting the location where the bolt comes out of the frame to lockup the 6-shot cylinder. This was necessary to maintain the integrity of the cylinder walls, particularly with high pressure .357 Magnum ammunition.

Consider a gun where the bolt window is located in the bottom center of the frame. When the cylinder is in battery, the bolt rises up from the 6 O’Clock position to engage the notch in the cylinder and lock it in place. If the cylinder is a 6-shot cylinder, then that would place the bolt notch directly over the center of the chamber, where the walls are thinnest. This creates a potential structural weakness—a place where high pressure gas could rupture the cylinder wall and escape.

You could solve this problem by increasing the diameter of the cylinder, to ensure that enough material remained after you cut the notch on the outside to safely contain the pressure, but that would require a bigger frame as well. Your small frame would grow larger and the gun would get heavier, to boot. Not ideal.

So Kimber took another approach, and shifted the bolt window outboard on the starboard (right, for you non-nautical types) side. By offsetting the bolt that direction, the notches on the cylinder could be moved so that they wouldn’t fall directly on top of the chambers. Instead, the notch could could be cut over the web that separates adjoining chambers, where the cylinder walls are thickest. This allowed Kimber engineers to safely contain Magnum-level pressures in a cylinder with the smallest outer diameter.

Going one step further, Kimber milled flats on the outside of the cylinder, which reduced the outer diameter. Instead of being a perfect circle, the cylinder now had more of a soft, hexagonal shape. The flats reduced the width of the gun at the point where it’s normally fattest, giving the 6-shot cylinder of the K6s a width on par with the 5-shot S&W Model 640 (1.39” versus the S&W’s 1.31”), as well as an identical weight (23 ounces). Kimber had built a 6-shot J-Frame!

To add icing to the cake, Kimber recessed the chambers, which came to be viewed as a premium feature, or a mark of Old World craftsmanship, after Smith & Wesson discontinued the practice on centerfire revolvers in 1982. Recessed chambers had their origins in the original Smith & Wesson .357 Magnum (the premium gun in the catalog), and were thought to be a necessary safety feature for the then-new Magnum cartridge in 1935. Time would prove the feature to be unnecessary for most centerfire revolvers, but the recessed chambers of the K6s feel like an upgrade and give the gun a cosmetic edge that contributes to the aura of a premium product, which plays directly into Kimber’s marketing strategy. As a practical matter, the recessed chambers did not require an increase in cylinder window length, allowing the K6s to maintain an identical overall length as the S&W Model 640 Pro (6.62” long, versus 6.6” for the factory semi-custom S&W).

Kimber K6S: Pocket Perfection?

When Grant was first approached by Kimber to consult on the development of the K6s, he realized it was an exciting, perhaps once-in-a-lifetime, chance to help create something special. So, the question is, after all the effort, is he happy with the final product?

“Absolutely,” he told me. He was “honestly surprised” with how good the first prototype was, and “was struck by the fact that the Kimber team had done a wonderful job of incorporating my inputs, while bringing some of their own ideas and sensibilities into the project.” The design only got better after that initial prototype, as the team refined it into the product we know today.

Kimber “has shown good consistency in production” and has exhibited a high degree of quality control on the K6s line, according to Grant. The samples he has seen come through his classes in the hands of his students have been absolutely reliable, with no breakdowns over the course of two days’ worth of high volume training.

He’s pleased with what he sees in the K6s, and if Grant is happy with the result, that says a lot. The Combat Tupperware crowd may not understand all the commotion over a 6-shot gun that runs in circles, but RevolverGuys understood from the beginning that there was something special about it. Hopefully, now that you know the story of it’s design and development, you’ll have an even greater appreciation for the K6s, and for the hard work and talent that went into creating it from a blank sheet of paper.

*****

RevolverGuy would like to thank Grant Cunningham for his generous time and assistance with this article. Please visit his website at http://www.grantcunningham.com for more information about his training courses and workshops, his outstanding books and podcasts, and his highly entertaining and educational blog. We would also like to thank Thomas Finch of Kimber, who served as part of the K6s development team at Kimber, for the insight he provided into the design and manufacture of this revolver.

Mike, thank you for writing this weapon up… I have been debating this gun for my next purchase for a while now. Sold. I imagine the shrouded barrel would help reduce muzzle flip although the engineers probably chewed off several inches of fingernail over the weight! I also want to thank you for the Colt vs. Smith trigger description. I don’t Colt much so it was educational. Lastly I wonder about the recessed chambers reducing the cylinder window… For a given cartridge length, would it not increase cylinder length? Thanks again for the write up.

Thanks Buddy, glad you enjoyed it. I’m going to talk more about the trigger in a follow up article about my T&E of the DC model (the black gun in the photos), because it’s really good. Regarding the cylinder window, I didn’t do a good job of expressing that thought, so I went back and corrected it. Hopefully it’s more clear now! The laws of physics still apply, even for a RevolverGuy!

The more I read about this gun, the more I feel like I might have to get over my requirement of being able to control the hammer during re-holstering, and just buy a K6S 3″. I really like the end on shot of the cylinder showing the rounded tip to the ejector rod. That looks like it might actually be usable instead of being a S&W/LCR cigar punch (as I call them). I still prefer the Ruger GP/SP style front lock-up, but since you explained the reasoning behind the choice, I am more willing to accept the lockup on the K6s.

Six shots, replaceable sights, near-perfect weight (especially in 3″ trim — I like a bit more weight), attractive grips on the 3″. The ONLY things I don’t like at this point are the more square trigger guard (because it requires a little more precision of me when I make a holster), the price tag (to be fair, I complain about that on almost everything), and the fact that I can’t block the hammer when re-holstering.

Mike,

Superb writeup. And for those of us who are ‘innards nerds’ – who must know how the mechanics operate – it answered a lot of questions. Essentially, S&W lockwork lives on in a modified form.

Do not be surprised if S&W and Ruger are working on matching the K6 within their own line, although the J frame would take some dimensional ‘modifications’ to be viable. (call it the J6 frams??)

I generally opted for wheelguns chambered in .357 Magnum – for those days when I just feel like I have to beat the snot out of my hands just for old time’s sake.

Glad you enjoyed the look “behind the curtain,” sir!

Is M frame taken? Maybe that’s an option..

Sadly the M-Frame is taken. We need to talk Mike into tracking one of those rare Smiths down…and writing an article about it!

And to add to the confusion, the M-Frame is small (I can’t remember if it is smaller than I or between I and J or just what). It really dashed my hopes for an elegant solution to wanting a 5-shot .45 Colt frame between the L and N sizes.

I don’t remember exactly where they fall on that spectrum, either. I passed on the opportunity to buy an I-Frame in .32 a couple years ago and have been kicking myself ever since!

Best write-up I have ever read.

Makes me think I’ll give the Kimber another

look.

Nonsensical I know, but I still prefer the Colt D

size or even the Smith K-frame snubby Model 10s.

I’ve never warmed up to the J-frame size.

Since it’s been out, I’ve been surprised at how

little I’ve seen about Grant’s association with

the gun and that has made me skeptical as to

how he really likes it. Also, has he had experience

with a lot of run-of-production guns.

His class experiences seem encouraging.

After initial gun magazine and internet

write-ups, it seems like there has been a dearth

of followup articles on the gun now that it

has been out for a few years. In other words,

no “track record” to speak of. Or maybe I’ve

just not hunted down the right places to

learn of it.

But, as I’ve said, I’ll give the gun another

look based on the write-up here which is the

most detailed I’ve ever seen.

Thanks Ed! Glad you liked it. Justin has been giving his (the 3″ version in the article) a workout already, and I just got my own copy (the 2″ black gun in the article–the DC model) this week. We’ll be running them and reporting back with a set of real “T&E” articles soon. This article was only intended to discuss the design and development stage of the gun, but we’ll be back with real field reports. I’ve shot the K6s at media events, but it’s not the same as running them through the paces on your own. Everything I’ve seen has been positive though, so far.

Grant was gracious with his time when I interviewed him. It’s my sense that he’s proud of how the gun turned out.

Going to need to shoot one. The company’s 1911s have in my experience been peerless.

Mike,

This is a little of topic. You wrote, “In the Colt’s method, the cylinder is locked at the rear only, with the aft tip of the spring-loaded ejector rod going into a hole in the breech face.” Am I misunderstanding something? I thought that Colt’s used a spring loaded release that projected forward into a recess in the rear of the cylinder/extractor star. Did they have a couple different approaches?

Other than my dad’s Python (and my Armscor look-alike if you want to count that), I really have very little experience with Colt’s so I am always curious to learn more about their guns.

Hi Greyson,

Nope, you’re not misunderstanding a thing. It was my error. Not sure what I was thinking (senior moment? Ha!) but it’s fixed now. Thanks for being sharp and catching that.

Mike,

Great job on this! I’ll echo what a couple of others have said already: this is the best, most comprehensive accounting of the K6s’ provenance I have ready anywhere, and I’m proud as hell for the privilege of running it here!

To the rest of you guys – we still owe you some range reports on the 3″ model and the DLC model Mike has. Not to spoil the surprise but so far this gun has impressed me to no end. Stay tuned!

Justin

Thank you! That’s very kind and it means a lot to me.

I look forward to running this gun and getting some trigger time on it. Field reports to follow from both of us.

Any chance for getting velocity comparisons between the two? I’m always interested in just how much difference the extra inch of barrel makes. I know, two different barrels and all, but I’d still love to see those compared!

Probably not, due to logistics. I have a chrono but no 2″ gun, Mike has a 2″ gun but no chrono…

This post on Lucky Gunner will probably answer most of your questions. The 686 and 640 used to take those velocities belong to me. I’d love to run my own test of this nature in the future, but don’t quite have access to that many revolvers. https://www.luckygunner.com/lounge/revolver-velocity-vs-barrel-length/

Here’s my go-to source for that question:

http://www.ballisticsbytheinch.com/357mag.html

Yep, read it, thanks! It’s just sort of an ongoing interest of mine, so every chance I get to learn more about it, blah, blah.. but I understand the logistics challenge.

Mike–thanks for the excellent article. I have one of these and it is by far my favorite small frame revolver. It’s nice to hear the background story.

My only gripe with the gun is its .357 chambering, as the large majority of owners, I believe, will shoot mainly or solely .38 specials in it. Same with S&W, I don’t believe they make an all-steel J frame in .38 special any more, they are all .357’s. A hot .38 special is all I care to shoot in these guns, including the all-steel ones. The problem with a .357 revolver shooting all .38 specials is that the gun is longer and a little heavier than it needs to be, and the extra jump the bullet makes going into the barrel robs it of some velocity (which the .38 can ill afford to lose).

Best,

Paul

Thanks Paul! I share your pain on this. My favorite J-Frame is a no-dash 640 in .38 Special that predates the stretched, .357 version. I wish that S&W continued to offer the steel frame .38 Special Centennial, because I like the shorter frame and don’t plan on shooting anything other than .38s in it.

I wouldn’t worry too much about velocity loss in the .357 cylinder versus the .38 though. I suspect that if there’s any loss at all, it’s negligible. I honestly don’t think it makes a difference on the terminal ballistics side of things.

+1 on all counts!

I’m glad y’all are putting these things through their paces. This is the first time I have seen the lockwork on Kimbers, and it’s extremely encouraging, but I have concerns about the dearth of people who have really run these beasties hard so far to want to dive in just yet, myself.

But I will be watching with interest!

Rest assured, the 3″ Kimber pictured here has been run pretty hard so far, and has a long way to go before the first field report gets filed. Stay tuned!

Justin

Thank you for the comprehensive write-up!

I have been interested in the K6 since it’s introduction, and your article helped assuage a lot of my concerns about a new revolver from a company that makes 1911s.

Once again, many thanks!

Stay tuned because we still have a long way to go with these little guns before the get the official seal of approval!

You all should have seen Mike at Kimber’s range location at the 2018 SHOT Show Industry Day at the Range. Mike had his note pad out while talking to a Kimber engineer. I was off shooting other guns and kept coming back to check on Mike. He was on page six of his notes and he and the engineer looked from a distance like they were hammering out global de-nuclearization doctrine.

Great review Mike! Thoroughly detailed to explain why the Kimber is so special!

Haha! Thanks buddy! We were certainly working hard to get good coverage for all the RevolverGuys in the audience. I look forward to our next Industry Day together!

Gotta admit I’m a bit jealous… if I start a blog do I get to go to industry events? ?

Ha! From what Steve and I could tell, that may have been the only “credentials” that some of those folks had! I wear several different industry hats when I’m there, not just RG.

I have guys like Mike so I DON’T have to go to those things!

Ha! Well played Sir.

I taught high school for 30+ years so I appreciate good detail in any kind of explanation, and this article satisfied that demand handsomely. Let’s hope other gun reviewers take a page out of your book, Mike, and do as extensive homework as you have before they hit the keyboard.

I have one question about the K6s that I haven’t seen answered anywhere, perhaps because it’s too obvious (I’m new to revolvers, the Kimber being only my 2nd; the other is a J-frame in .38). How does the firing pin block work in this revolver? I know S&W uses one approach and Ruger the opposite approach with its transfer bar, but looking at the photo of the Kimber’s skeleton, I can’t figure out which is in play here (obviously, mechanics are not my forte!).

Hi John, thanks for your kind words and welcome aboard! We’re glad to have you here. I hope you’ll stick around and enjoy the other great articles on the site.

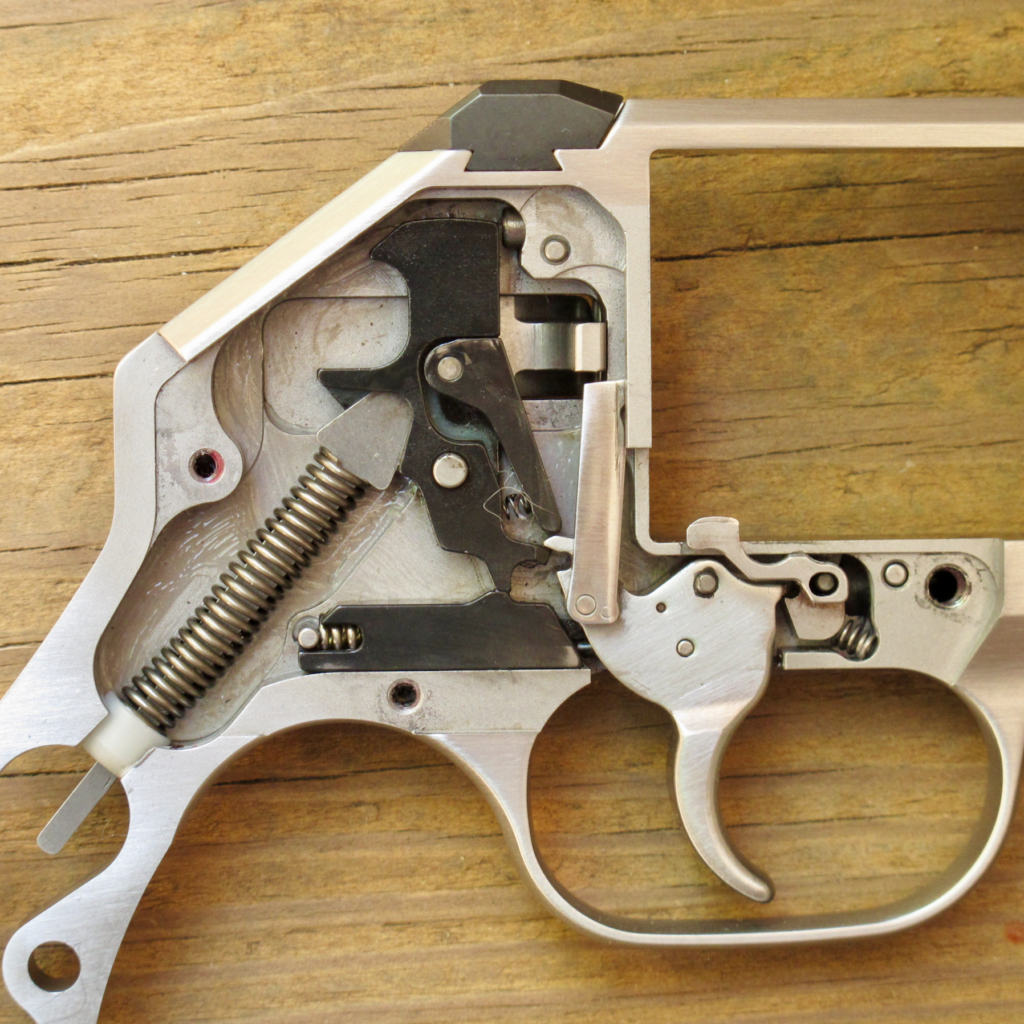

The K6s firing pin design is the functional equivalent of the S&W hammerless system. The firing pin is held in place by a crosspin that runs transverse through a firing pin housing. In the cutaway picture, you can see the head of this crosspin in the top right corner of the interior space, directly below the forward edge of the rear sight dovetail.

The firing pin has its own spring, which is hidden from your view by the housing. You can see the tail of the firing pin sticking out and being sandwiched between the black hammer on its left, and the firing pin housing. Just look to the left of that crosspin we discussed, and you’ll see the firing pin there.

When the trigger is pulled, the hammer is cocked back against the mainspring, and when the sear trips, the hammer flies forward to strike the tail of the firing pin. The firing pin compresses the firing pin spring, and the head goes through the breechface to strike the primer. When the trigger is allowed to move forward after ignition, the hammer moves back to its at-rest position, off of the firing pin tail. When this pressure is released, the firing pin spring relaxes and pushes the firing pin rearward, into its resting position, and the head no longer pokes through the breechface.

There is no intermediary between the hammer and the firing pin in this system. In the (post-1940s) S&W revolvers with external hammers, there is a hammer block safety that prevents the hammer from moving fully forward unless the trigger is pulled. This piece moves down when the trigger is pulled, which allows the hammer to strike the frame-mounted firing pin (or, on older models, allows the hammer-mounted firing pin to go through the breechface).

On the Ruger revolvers, it works the opposite way. The transfer bar safety doesn’t rise into position until the trigger is pulled, so the hammer cannot strike the frame-mounted firing pin until the trigger is pulled back and the transfer bar goes up, between the hammer and the tail of the firing pin.

On the S&W hammerless models and the K6s, neither of those parts are present. There is nothing that fits between the hammer and frame/firing pin to provide safety. On these models, safety is ensured by the firing pin spring, and the little bump on the rebound slide.

The firing pin spring is strong enough that it prevents the firing pin from contacting the primer unless it has been struck by a full blow of the hammer. So, if you dropped the gun, the firing pin wouldn’t have enough inertial energy to overcome the spring and strike the primer hard enough to ignite it.

The rebound slide (the black piece that sits horizontally at the bottom of the interior, in the cutaway photo) has a bump on it that interfaces with a bump on the bottom of the hammer. These two bumps bear against each other, and prevent the hammer from moving forward unless the trigger is pulled, so that’s your safety which prevents the hammer from moving forward if the gun is dropped.

So, the hammer can’t move forward unless the trigger is pulled, and the spring loaded firing pin can’t move forward (with sufficient force) unless it is struck with a full power blow from the hammer, which only happens when the trigger is pulled. That’s how the K6s internal safeties work.

How’d I do, teach?

Well, Mike, you’d get an A+ in my class, no ifs, ands, or buts about it! Not only did you answer my question in an easily understandable fashion (I copied off what you wrote and read it while viewing the cutaway above), but you gave me a lesson in vocabulary associated with the internals of revolvers. (Now my homework will be to study that terminology till it becomes familiar to me. At my age, memorization isn’t as easy as it used to be, but give me an hour or so and I’ll be slinging around those terms the way Jerry Miculek slings lead!)

I can’t thank you enough for taking the time to explain this feature of the K6s; as I said before, I couldn’t find it elsewhere on the Internet and, believe me, I tried. I’ve already bookmarked the Revolverguy.com site and I’ll be sure to return soon.

Thanks once more.