The revolver was the mainstay defensive handgun in America through the mid-to-late 20th Century. While a variety of autopistols (many of them John Browning designs—all rise!) were popular with American gun carriers as well, and eventually supplanted the revolver as King, it was the revolver that filled most holsters, pockets, and nightstands.

One of the reasons for this supremacy was the widely-held opinion that the revolver was more reliable than the auto.1 When the inevitable Revolver Vs. Auto comparison was made, it was generally conceded that a well-made revolver suffered fewer stoppages and malfunctions than the equivalent autopistol, and was more “trustworthy” as a defensive arm. The autos generally boasted greater capacities and faster reloads, and had triggers (at least, in the single action format guns) that were easier to work, but the revolver’s reliability often trumped all of that for most users.

In the friendly (and not so friendly) arguments between the two sides, revolver advocates frequently resorted to the shorthand that “revolvers don’t jam” as a way of promoting the general reliability of their choice, and over the years, it became so commonplace to hear that claim around the gun counter, stove, and campfire, that many folks actually started to believe it!

Guess what?

There aren’t many places out there on Al Gore’s internet where you’ll find a more spirited defense of the revolver than here, in these pages, but since we place a premium on truth and accuracy ‘round these parts, we have to admit that revolvers most certainly do “jam,” from time to time.

In fact, sharp RevolverGuys know there’s a lot of ways that a revolver can go down, mid-stride. Some are the fault of the gun, many are our fault, and others can be blamed on the ammo we stuffed into the chambers (making it our fault, again, sometimes).

Since we’d like to avoid hearing one of the two “loudest sounds in the world” (a “click,” when we’re expecting a “bang,” or the equally-shocking opposite), it’s probably a good idea for us to do a quick rundown of the various ways a revolver can burp. Some of these are true malfunctions (where the machine doesn’t work as designed because it’s broken, or has some kind of defect), while others are stoppages (where the machine doesn’t work as designed because we failed to maintain, operate or feed it properly), but neither one of them are good. The latter (stoppages) can usually be fixed on the spot, by the shooter, but the former (malfunctions) usually require tools and the help of an armorer or gunsmith to correct.

So, without further adieu, here’s a brief look at some of the more common ways you can have a bad day with your revolver.

Malfunctions

There’s a lot of different parts that can break on your revolver, but here’s some of the more common failures (and a few uncommon ones) to keep an eye out for:

-

-

Broken spring. A broken mainspring, sear spring, trigger return spring, rebound slide spring, firing pin spring, extractor rod spring, extractor bolt spring, or cylinder stop spring can make your revolver stop revolving. Sometimes these springs fail due to cumulative fatigue, but other times they fail because we monkey with them, in an effort to “improve” something. The best ways to avoid a spring problem are to inspect them regularly, replace them at the appropriate intervals with an OEM or high-quality aftermarket spring, and stop futzing with them! Also, use a spring of appropriate power for the task—some of the lighter replacement springs that are offered to “improve” revolver actions will break prematurely because they’re not robust enough for the job;

-

Broken firing pin. A broken firing pin, or “hammer nose,” can also stop making your gun go “bang.” Although live fire will certainly degrade this part over time, it seems like most of the damage I’ve encountered has its roots in dry fire. The firing pin will sometimes break in both rimfire and centerfire guns if you aren’t using some kind of “snap cap” or dummy ammo to cushion the pin’s strike during dry fire. In the case of the rimfires, the tip of the pin may strike the edge of the chamber and break. In the case of the centerfires, a frame-mounted firing pin may slam into the firing pin bushing with too much force if the pin doesn’t encounter the resistance it normally gets from the primer, and break along a stress riser. Once again, your best solution is to inspect them regularly, use the right ammo (ammo with excessive pressure may accelerate wear), keep the channel clean, replace the firing pin spring (as equipped) at the appropriate interval, and use some kind of snap cap or dummy round when dry firing;

-

-

-

Broken or worn hand. The hand is a high wear part, particularly in the Colt revolvers, and will eventually wear or deform to the point that it doesn’t turn the cylinder in proper fashion, causing a timing issue. In an extreme case, it may even break, outright. The best way to care for the hand is to keep the hand and ratchet clean, inspect the hand regularly, and replace it at the proper interval;

-

-

-

Worn ratchet. The ratchet gets worn from the hand bearing against it in normal operation, but can also be damaged if the cylinder develops excessive endshake. In the latter case, the ratchet gets smashed into the breech face at the end of the cylinder’s rearward thrust during firing, and can be deformed. A worn or damaged ratchet will produce timing errors that are best avoided. The best ways to protect the ratchet are to keep it clean and free of debris, use the right ammo (ammo with excessive pressure will accelerate the development of endshake), and monitor the gun for endshake. If excessive endshake develops, correct it before you shoot the gun again;

-

-

-

Broken or worn cylinder stop. The cylinder stop (or “bolt”) is another high wear part, which can deform to the point that it doesn’t lock up the cylinder properly, and cause a timing issue. Firing a revolver quickly in double action will accelerate the wear on the bolt, because it has to stop the inertia of a rapidly rotating cylinder. The same occurs if you “fan” the hammer like a movie cowboy. The best way to care for the bolt is to keep it and the cylinder notches free of debris, inspect it, replace it at the proper interval, and stop watching all those B-westerns;

-

-

-

Endshake. We’ve mentioned this already, but if the cylinder is allowed to develop excessive fore-aft play, it could eventually beat the gun to death. The ratchet could be damaged, and the center pin/bolt hole in the breech face could be damaged. Additionally, the headspace could be increased to the point that the gun has ignition problems. This condition is easily detected if the gun is properly inspected, and easily fixed by a qualified armorer or gunsmith;

-

-

-

Internal lock failure. Fortunately, this one is rare, and it can usually be avoided through careful ammunition selection. A hard-kicking load in a lightweight S&W revolver may cause a locking flag, or the lock mechanism itself, to jam, so that combination should be avoided if possible, or at least tested until reliability can be established. The small handful of folks who actually use the lock should also be careful to ensure the key is fully turned before it’s removed, to ensure the internal mechanism is parked in the right place;

-

-

-

Broken hammer, trigger, or rebound slide stud. These malfunctions are problematic, because there’s really very little you can do to prevent them. A broken hammer, trigger, or rebound slide stud will usually kill the gun on the spot, but you might get lucky for a short while and only suffer a heavy and rough trigger pull, until all the internals finally get out of alignment. The most common of these is the hammer stud failure, and in Smith & Wessons, this seems to occur most frequently in aluminum-framed guns, because the hammer studs in those guns are made of a weaker material (aluminum) and are installed with a less robust method (they are staked in place). Older, steel-framed guns may suffer a hammer stud failure because of stress-risers in the old, collared-stud design, but S&W changed to a new stud design (which lacks the collar) and installation process (which includes pinning and brazing the stud into place) on current-production, steel-framed revolvers, which has virtually eliminated the issue in the new guns. Trigger stud failures are rare, as are rebound slide stud failures, unless you happen to damage them during disassembly, but they do happen occasionally. The best preventive measures involve proper cleaning and lubrication, and using proper care and tools when you disassemble and reassemble the gun. It’s unlikely you’ll detect any cracks during inspections, but it won’t hurt to try. The best mitigation strategy is to carry a backup gun;

-

Cracked forcing cone. A cracked forcing cone can result in cylinder binding, velocity and accuracy issues, and, eventually, a frame failure. Certain designs, like the older K-Frame Magnums, are more susceptible to this problem, especially when they are fired with Magnum ammunition loaded with light-to-medium weight bullets. The best way to avoid this problem is to be careful with ammunition selection, and conduct routine inspections;

-

-

-

Broken rebound lever. This part may break on an older Colt DA revolver, because it’s a weak area in the design and the part must be hand-fitted during assembly (which may potentially weaken the part). RevolverGuy Dean Caputo advises that fixing this issue is difficult, due to a lack of suitable replacement parts, and the requirement to hand-fit them. Outside of keeping the gun clean and lubricated, and conducting periodic inspections, there’s really not much you can do to prevent this malfunction from occurring, which is why a lot of these older Colts need to be babied. Get yourself a new Colt if you want to carry one or shoot it hard.

-

Stoppages

Since stoppages are mostly attributable to either the shooter or the ammo, it’s helpful to break them down this way.

Common shooter-induced stoppages:

-

-

Failure to clean. If a shooter fails to keep critical parts and areas clean, the gun will stop working. A buildup of crud (including carbon, unburned powder residue, lead, etc.) under the extractor star, on the cylinder face or forcing cone, on the cylinder yoke barrel, in the firing pin channel, in the action, in the hammer channel, or in a recessed chamber mouth, can all shut a gun down. The solution here is simple—keep it clean! Use proper tools, products and methods during routine maintenance, do a quick clean with a brush or rag during extended range sessions, and use clean ammo that doesn’t leave a lot of extra fouling, lead deposits, and unburned powder behind in the gun;

-

-

-

Failure to lubricate properly. Like any machine, a revolver needs lubrication on the right parts to avoid excessive wear and make it run smoothly, but in most cases, revolvers don’t burp from a lack of lubrication. Instead, they burp when they have been lubricated too much, or have been lubricated in the wrong places. Oil will attract dirt, and an excess of it, or the presence of oil in the wrong place, will gum up the works. To avoid this, use a needle oiler to put the lube in the right place, in the right amount, and don’t oil places that should be kept dry, like the area under the extractor star;

-

-

-

Failure to maintain. Revolvers are simple to operate, but they do require some attention to keep them in working order. One of the most common lapses is a failure to keep screws tightened. An extractor rod that unscrews, a yoke/crane screw that unscrews, or even a sideplate screw that unscrews, can all bring a revolver to a grinding halt. We mentioned endshake before as a malfunction, but it has its roots in a failure to maintain the gun in good order. Avoiding these problems is simple. Revolver shooters should routinely check and tighten screws (with a screwdriver that fits properly) during maintenance and before shooting activities. They should also conduct regular inspections, and have their gun serviced at the proper intervals by a qualified armorer or gunsmith;

-

-

-

Failure to maintain—crane / yoke screws. These screws deserve a special mention because there are several ways things can go wrong with them. In the older Smith & Wesson designs, installing a sideplate screw where the yoke screw is supposed to go (a common error) can allow the cylinder and yoke assembly to slide forward, off the frame (as when using a push-feed speedloader design). The same can happen on Colt revolvers (and newer Smith & Wessons, which use a similar screw design) if the crane screw has a worn spring or plunger (we even had one RevolverGuy reader who encountered this issue on a brand new King Cobra, because a weak, OEM spring allowed the plunger to retract too far). Keeping your parts straight, and replacing worn/out-of-spec parts is the cure for these issues. By the way, some Ruger SP101s have a related issue with their cranes, where they can slide forward when the cylinder is open and pressure is placed on the rear of the cylinder—this displacement will prevent the crane and cylinder from closing, until you “bump” them back to the rear, and into place;

-

-

-

Operator error—short stroke. If a shooter doesn’t allow the trigger to return forward far enough after the gun is fired, he may “short stroke” the gun and interrupt the operating cycle. Shooters who have a habit of “riding the sear” or releasing the trigger to “reset” on their autopistols are particularly likely to short stroke a revolver trigger and not have the gun fire when they want it to. The cure here is practicing and executing good technique, which involves letting the revolver trigger return fully forward before pulling it again, instead of feeling for the “reset.” Some revolvers, just like some autos, have a “false reset,” so don’t get tricked by that—let the trigger return fully forward before you start pulling it again;

-

Operator error—open cylinder. Failing to close the cylinder all the way, or holding the gun in a manner that the cylinder release is inadvertently actuated while firing, will cause the gun to stop working. A good grip, good reloading technique, and keeping the area under the extractor star clean, will be the cure for this issue;

-

Operator error—bent extractor rod. A sloppy, off-center, or angled strike on the extractor rod can bend it and prevent the cylinder from closing or turning. Good reloading technique is the key to avoiding this problem;

-

-

-

Operator error—sprung yoke/crane. A cylinder that is slammed shut or flung open can bend the yoke/crane, or damage the center pin/hole, and cause all kinds of problems with lockup and timing. If you don’t abuse your equipment, you won’t have this problem, so avoid the “Hollywood flip” when you’re opening or closing the gun, and you’ll be OK;

-

-

-

Operator error—case under star. A case that’s not fully extracted can angle outboard enough that the rim slips underneath the extractor star, and the case is rechambered, underneath it. This will completely deactivate the gun until the case is removed from the chamber with fingers or a tool. This stoppage typically occurs when the shooter fails to deliver a full-power, full-length stroke to the extractor rod, as when “pumping” the extractor rod. Proper reloading technique is the solution, here.

-

Common ammo-induced stoppages:

-

-

Bad primer. Of all the ammunition problems I’ve seen, the most common culprit has been the primer. A missing primer, a backwards primer, or a “dud” primer will prevent ignition when the hammer falls. The first two are manufacturing errors, but the third may be the fault of either the manufacturer or the shooter. How can a shooter kill a primer? By not storing the ammunition appropriately (dry and cool), or by getting sloppy with a penetrating solvent/oil when cleaning the gun (pro tip: WD40 is NOT for cleaning guns!). Fortunately, a fresh, new primer/round is usually just a trigger pull away with a revolver . . . unless it’s just not your day, and you’ve got another bad round, or a fired case, up next. In that case, a backup gun or a good reload is your salvation. One other strange primer issue is a primer, or piece of primer, that falls out of the case’s pocket, and binds the action. This rarely happens, but if it does, you may have to force the cylinder open and clear the debris to get your gun back in action. Again, you may not see this in a lifetime of shooting, but there’s a few guys who have encountered it, courtesy of our friend Murphy. Most primer issues are fixed through a proper inspection protocol, and keeping your ammunition clean and dry—easy stuff;

-

-

-

High primer. A primer that isn’t seated flush into the primer pocket can stick out far enough to prevent cylinder rotation. A proper inspection will usually allow you to detect this problem before the ammo goes into your gun (pro tip: pull the tray of loaded cartridges out of the box, and eyeball the whole tray—anomalies will be easier to detect when all the cartridges are stacked together, in a row). Additionally, there’s an operational check that involves holding the hammer back far enough that the cylinder stop is disengaged, and spinning the loaded cylinder to check for unwanted drag (you won’t be able to do that with your “hammerless” gun, though). If a primer starts to work its way loose as you’re firing, you may have to force the cylinder open and reload, to get the gun working again;

-

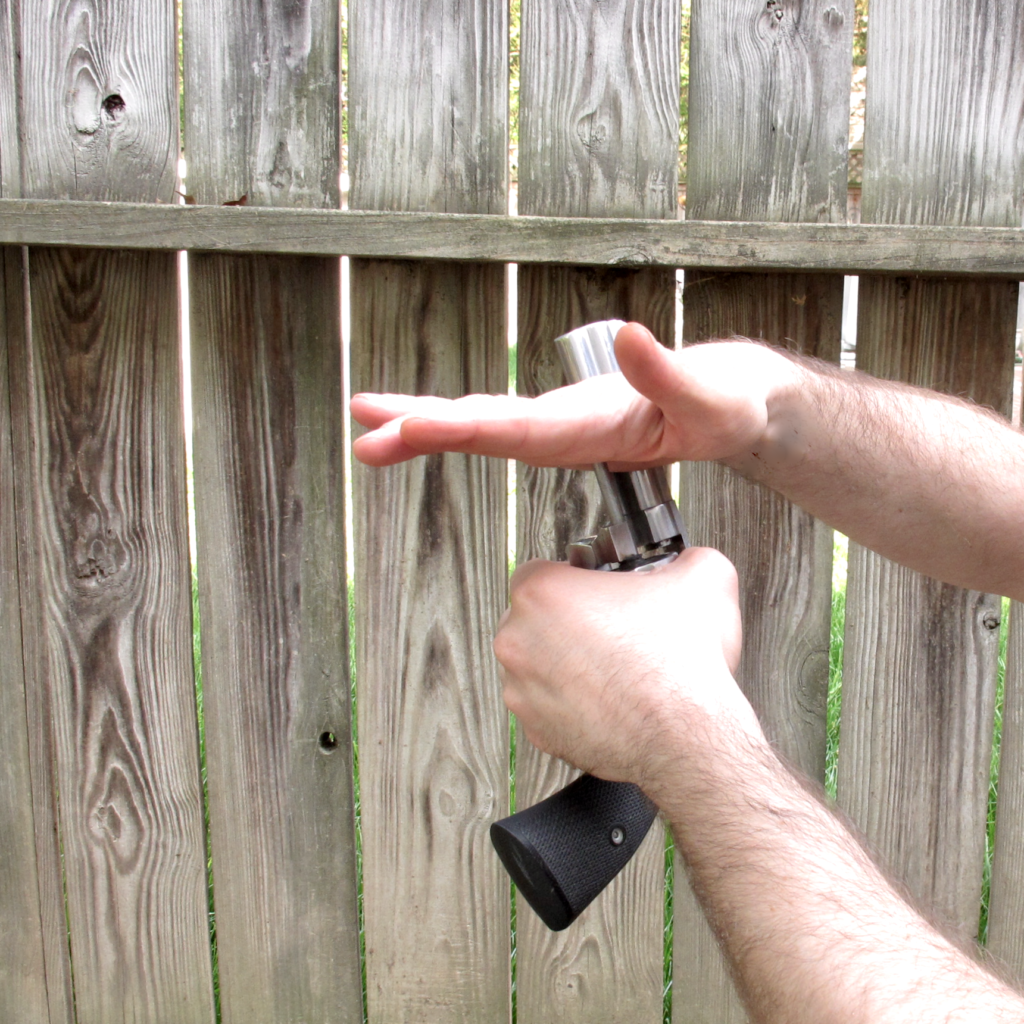

Primer flow. Yep, that pesky primer is acting up, again. In this case, the primer material actually flows backwards into the firing pin hole/bushing in the frame, which will prevent cylinder rotation. This usually occurs as a result of very high pressure (or overpressure) ammo rupturing the primer while the firing pin is still in contact with it, but RevolverGuy readers may recall that manufacturing defects in the gun can also contribute to it. It’s amazing how little material is necessary to completely tie up the gun—just a little shard can exert enough leverage to bring things to a halt. This condition is usually avoided through proper test and evaluation of your ammo, but if it occurs in the field, the gun’s cylinder may have to be forced open to shear off the offending material, before the gun can be returned to action. Sometimes you can accomplish this with more force on the trigger, but usually the cylinder has to be forced open to break the jam;

-

Bad powder. It’s rare to get a factory case that wasn’t charged with powder, but it happens more frequently than we’d like with handloaded ammunition (which raises a related concern, that there’s another case with TWO charges of powder lurking in your supply, and maybe your cylinder). Improperly stored and maintained ammunition can also suffer powder contamination from water, solvents, or oils that kill the powder and prevent ignition. A shooter should always be alert for that small “pop” which warns you that the primer was good, but your powder was not, and you might have a bullet stuck in the bore, or the barrel-cylinder gap. The latter prevents the cylinder from rotating or opening, which is both a curse and a blessing—a curse because it’s harder to fix, but a blessing because it prevents you from firing another round behind the squib and blowing up the gun. Again, proper inspection protocols and keeping your ammo clean and dry are the best solutions for this problem. If you do get a bullet stuck in the bore, as a result of contaminated powder (or a contaminated primer), you’ll need a tool to fix it, like a squib rod or “dejammer”—a backup gun would be helpful, in the interim. By the way, did you know this problem was one of the reasons why Fitz liked to shorten barrels? The ammunition of the era wasn’t always reliable, and it was more likely that a squib would clear a short barrel, and not get stuck;

-

-

-

Pulled bullet. A related condition is a bullet that “walks” out of the case as a result of inertia, then binds against the frame, preventing cylinder rotation. We see this most frequently in the revolvers that fire autopistol ammunition with a taper crimp, but it can also happen with revolver ammunition loaded with moderate-to-heavy bullets in lightweight revolvers. Careful ammunition selection (paying attention to things like crimp style and whether or not the bullet is cemented/sealed with Black Lucas), and a proper test and evaluation process, will allow you to avoid this problem. If it happens in the field, the creeping bullet will have to be forced back into the case with a tool, to get the cylinder to turn or open—not something that you’ll want to do in the middle of a fight;

-

-

-

Bent clip. The “moon” and “half-moon” clips used in some revolvers may bind the cylinder and prevent it from rotating if they are bent. These clips are relatively fragile, and are prone to being bent when cartridges are loaded into the clip, and fired cases are removed from it. They may also bend if they are not protected in transport/carriage. The best way to avoid this problem is to buy robust clips, use a dedicated tool for “demooning” clips, inspect the clips regularly for defects, and carry them in a pouch that’s designed to protect them from damage;

-

-

-

Crushed case. A case mouth that has been crushed during the loading process (usually when a bullet is seated) or a case that has been crushed/dented during transport/carriage may prevent the ammunition from loading into the chamber. This is a particular problem for reloads that are carried loose in pockets, instead of in carriers that are designed to protect the ammo from damage. If you’re able to force one of these deformed cases into a chamber far enough to fire it, the flaw may prevent the case from being properly extracted, after it expands from being fired. The solutions here are to do routine inspections of your ammunition, and carry reloads in a manner that they are protected from damage;

-

Incompatible ammo. Both the ammo and the shooter are at fault, here. While some ammunition types may technically “work” in a given firearm, they may be poor choices due to their tendency to leave excessive amounts of lead, fouling, and powder residue behind, in the gun. This is especially common in rimfires and centerfire snub revolvers. A change to a load with a jacketed bullet, or a powder charge that is more completely consumed, may be in order to prevent a stoppage.

-

That’s all, folks!

That seems like quite a list for a gun that “doesn’t jam,” doesn’t it?

It’s certainly a longer list than you might think of, at first, but the good news is that most of these malfunctions and stoppages can be prevented with proper inspections, maintenance, and shooter techniques. With just a little effort, you can ensure that your revolver demonstrates a level of reliability that would make most autopistols jealous!

So, care for your gear, pay attention to what you’re doing, and be safe out there!

*****

Endnotes

-

We hesitate to call it more than an “opinion” here, because it’s hard to make such a general assertion without some additional context. With the guns and ammunition of the period, the revolver was indeed generally more reliable than its autopistol counterpart for most users, but varying conditions could change the results. In the trench warfare of World War I, for example, the “closed” auto was probably more reliable than the “open” revolver. This begs a conversation we’ve had before, about how the revolver is generally more resistant to neglect, and the auto is generally more resistant to abuse. Reliability, then, is not an absolute, as much as it is a sliding scale that’s dependent upon conditions (environment, ammo, shooter technique, maintenance, etc.).

Over the years going back to the late 1970’s, some of them shooting revolvers, I’ve had several of these problems. I’ll list them in order of decreasing embarrassment, except the last one.

1) Bent Ejector rod, new model 629, definitely my fault.

2) Squib load, SP101, my hand load, but I was aware enough not to fire a second shot.

3) Pulled bullet, several times in my teen age youth before I figured out what is a proper crimp.

4) Excessively sticky extraction, not my hand loads.

5) Broken mainspring (factory), old model 629; I was shocked.

6) Broken hammer stud, old model 629; I was shocked and angry.

7) Weakened mainspring (factory) model 60; who knew that coil springs can age?

8) Worn hand model 617, somewhat early in life, after more than 1 gallon of spent .22 cases.

9) Worn hand new model 629, after an uncountable number of 44 magnum rounds.

10) Forgetting to unlock the Hillary hole while hiking in boonies.. Hey, when you get old, you forget things.

What separates old from new models in the list, is the type of studs used by S&W. I have no complaints about the current crop of Smith&Wessons other than I really should get around to removing the internal locks & plug the Hillary holes.

None of this experience has turned me off revolvers. But I did end up learning how to fit new hands on a S&W revolver. The Kuhnhausen shop manual for S&W revolvers is a God-send.

—

All these revolver articles are delightful. Someday you might take your compiled posts and convert them into a coffee table book.

Thanks Some Guy! That’s quite a list, there. It sounds like you’re the kinda guy who buys his reloading lead in freight car quantities! I can see how you managed to wear out some guns!

I took a S&W Armorers course in the revolver era. I questioned the instructor about dry firing S&W revolvers and he said go ahead because in the 20 years he had been at S&W he had only replaced one “hammer nose” (firing pin) and it was bent.

I’ve never had an issue with a hammer nose, but know some who have. The frame mounted pins are an entirely different beast, though. Particularly if you make them out of an inappropriate material, like the Ti pins on the original Kimbers.

Excellent article, Mike. If you carry and shoot revolvers long enough, you will experience both stoppages and malfunctions with them. Hopefully it will happen during practice or competition when the stakes for failing don’t involve bloodshed. S&W’s endurance package changes of the 1990s slightly altered the look and feel of their classic revolver design, but it improved them in critical areas. One of the most noticeable changes was switching to the frame mounted firing pin from the classic hammer nose design. It looked different and made the action feel and sound weird but fixed a critical weak point in the guns. I experienced a broken hammer nose in my PPC open revolver in a match; it rendered my heavy barreled model 10 an impact weapon until it could receive armorer level care. You sagely mention yoke screws as a weak point, and the new ones aren’t exempt. The stopwatch gorilla of competition will cause shooters to use more force than required encouraging speedloaders to dump their payload. Cylinders leaving the gun and sailing towards the dirt can result from this. It’s amazing how sharp the underside of an extractor star can be. Frantically trying to clear a .38 case from underneath the extractor star of a .357 Magnum revolver with the clock ticking will prove that. Hemorrhaging points and blood from this activity in a match will surely emphasize the importance of correct extractor rod manipulation technique. Great points you make, Sir.

Kevin, thanks for sharing your valuable experience! The audience may not know your extensive background with working on these guns, but take it from me folks, I always pay attention when he’s talking. Interesting that you picked up on the yoke screws and the potential for damage and failure with a push loader system . . . kinda makes one wonder if a twist loader might be less stressful on the gun, or maybe a technique where the gun is transferred to the support hand for loading, versus maintaining a firing grip and loading with the support hand. That could be a good barstool or campfire discussion someday. You’re right about the extractor—I’ve been bitten by that part, too.

Thanks for that, Mike. I stopped using Safariland Comp III’s in my guns because I had the tendency to resort to brute force when they would bobble, or more likely when I would bobble them. I had much better luck switching back to Comp II’s like I carried with fighting guns. Swapping SWC’s for RNFP bullets helped, too. At least for me, a Comp II or an HKS loader caused much less grief and wear on critical parts of my competition revolvers. Although very similar in design, Jet Loaders oddly work better for me than Comp III’s, too. I use my strong hand to load while my support hand holds the cylinder. I agree that this method causes less stress on the yoke screw/yoke engagement than maintaining a firing grip while loading with the support hand- especially if you have the tendency to go full gorilla. S. Bond, like you I have only had that one hammer nose break, and that gun saw many, many hammer falls- live and dry. Not enough to make me cut my old guns loose, but definitely something to keep an eye on.

Mike, another well done in depth analysis of the many little things that can disable an otherwise engineering marvel. If one stops and thinks about the many things going on with a double action revolver – you have a trigger going forward and back, unlocking a cylinder, turning a cylinder on its axis, working a hammer that also goes forward and back, and holding everything in place until the bullet leaves the barrel, it is an amazing device ! And having one so compact as to fit in a pocket, Sam Colt would have been jealous.

Kevin, I my 55+ years of consuming my share of the world’s supply of smokeless powder and little lead slugs, I’ve only had one S&W hammer nose break, and thankfully it was during range practice. Losing one in competition is enough to shake confidence in your equipment . . . on the street, well, let’s not go there.

I have had S&W extractor rods back out in competition (used to shoot IPSC in the 80s with my revolvers, later IDPA) – the cylinder either won’t come out when you want it to, or won’t go back in when you need it to. Time ticks as you screw things back into place. Springs are definitely a wear part. Any time I would pick up a new-to-me second hand S&W, the first thing on the agenda was a set of new OEM springs. On later guns with spring loaded cylinder retaining screw, even that spring was replaced. It’s not that I don’t trust used springs, it’s that I don’t trust old used springs.

Many folks don’t realize the amount of unburned powder that can accumulate around a revolver’s cylinder after even a small amount of shooting. I managed to figure out while in patrol school that keeping a rag handy in my pocket while on the training range (when we’d shoot upwards of 100-150 rounds a day), and ‘cheating’ the residue by doing a quick wipe under the extractor did wonders to help things along. I used it between stages in the IPSC and IDPA days as well.

A person who relies on the revolver as their life insurance, and who otherwise has not given it much thought, might consider a pre-deployment checkdown, much like pilots do on aircraft. Clean cylinder and extractor, and under the extractor, tight screws, snug ejector rod, clean cylinder window, thumb your carry ammo to make sure all are flush fit. It takes less than a minute to make sure your gear is operational.

Speaking of ammo — rotate it out regularly. In the overall scheme of things, as Mike aptly pointed out, the ammo is the unknown variable. A Revolver is an open system, meaning that heat, moisture, dust, dirt, etc, can and will find its way to the cartridges and take their toll. I learned this early in Florida, especially being around salt water, that salt air loves nibbling at nickel plated revolvers and cartridge brass (as well as shotguns and shot shells). Nickel plated cartridge cases are not immune to the effects of salt air (ask me how I know). I quickly adopted a daily ‘interim cleaning’ protocol at the end of my shift. I could deal with a malfunctioning patrol car, just not a malfunctioning sidearm. I was so happy when the stainless steel revolvers were issued – yes, stainless steel can rust, but you at least have a chance to stay ahead of the salt air. Dirty ammo can result in extraction difficulties at best, and failures to function at worse. Ammo is cheap; the alternative, well . . . not so much.

I hope everyone who reads this article takes the time to scroll down and read the comments too, because they’d be missing out on the best part if they skipped them. I really appreciate you sharing your extensive experience and wisdom with us, Sir! I’d love to hear more about what you did for preventive maintenance in the Florida salt air and humidity. That’s gotta be one of the toughest environments around, so if you found a workable solution there, it would probably work everywhere else, too.

BTW, I think dealing with humidity and corrosion is part of the backstory on those guns where WD40 killed the primers. Lazy guy wants to wipe down the gun to prevent rust, so he hoses it down with WD40 and wipes it off with a rag, without ever unloading it, first. Penetrating oil does its penetrating thing, and he gets rewarded with a light pop or a click at his next range day (if he’s lucky).

You covered a lot of important ground here, Colonel Mike. Over many years, and via the hard way, I’ve learned the necessity of just enough (but not excessive) firearms cleaning, lubrication–and inspection.

One of the most important lessons for me was not allowing people I didn’t know very well handle my guns, especially revolvers. Invariably, when holding a double-action revolver of mine, these folks would perform the “Hollywood flip” and acted as if I would approve of their stupidity. So, in my mind they’re guilty of such nonsense until they can prove themselves trustworthy.

Another early lesson was to avoid buying firearms (and other things) from those who showed signs of neglecting and abusing their gear, as if this foolishness demonstrated that they were “real men” (or women) who could not be bothered to take care of their stuff.

Amen to that, Spencer. I think we’ve all been bitten by something like that, and learned the hard way! I cringe every year at SHOT Show when I see people mishandle the custom 1911s and drop the slides on empty chambers from slide lock—it’s worse than fingernails on chalkboards!

Good work as usual. I will send this to my revolver-curious friends. One of them did the Hollywood Flip with my S&W 64-3, and got a polite, short lecture starting with “Never, ever do that.” But had seen it in movies…

As a novice reloader, I had a squib at the range. I am Type-A and had done my homework first, so I heard the pop andknew what had happened.

Just to be sure, I loaded another revolver and fired it. Second squib! At home 98 bullets of the 100 I had reloaded had to be pulled. My scale had drifted off 0. Now I calibrate it every session and check every fifth round.

Yikes! I bet having to pull 98 bullets cemented that lesson for you in a very meaningful way. I’m sure there’s some high-volume reloaders who would balk at checking every fifth, but I bet you’ll never have a repeat of that problem again. Good advice for us!

I don’t see the Hollywood Flip on screen much, anymore, because the bottom feeders seem to hog all the screen time. I suppose we can be thankful for that, but there’s always some kind of stupidity that will leave us shaking our heads anytime there’s gunplay.

Fantastic article Colonel Mike! I never knew that revolvers had so many potential issues. Fortunately I witnessed only one serious stoppage in the line of duty.

We were in a vehicle pursuit and finally boxed in the perpetrator when he hit rush hour traffic. He responded by ramming the car in front, the put his car in reverse and rammed my unmarked vehicle. As I kept two feet on the brake pedal my lieutenant, hopped out and drew his Colt Detective Special but the action locked up when he attempted to remove the suspect from the vehicle.

The good lieutenant retreated to our passenger door and yelled, ” Mike – throw me a gun!” I reached down to my ankle holster and tossed him my S&W Model 36.

All ended well with one dirtbag off the street. I later learned that his Colt ‘froze up’: the cylinder refused to rotate and the hammer couldn’t even be cocked for a single action shot. I don’t know the exact mechanical malfunction but the gunsmiths at Rodman’s Neck corrected it promptly.

One week later my lieutenant was ambushed while executing a search warrant

and he was able to fire all six rounds from the same Colt D. S. Unfortunately, the armed subject had the LT pinned down with seemingly endless firepower. The rest of the search warrant team had to slide ammo pouches, speedloaders, and additional revolvers down a narrow hallway to the LT to keep him in the gunfight. Eventually the bad guy’s firearm ran dry and he was apprehended.

After this busy week, my boss earned his nickname, “Throw me a gun!”

So, the first question is whether or not the motor pool guys were able to get the bench seat in your car cleaned off, because, HOLY COW, that had to leave a spot. Ha!

Drawing from an ankle rig is always a hoot, but trying to get your gun out while you’re standing on the brake pedal must have been twice the fun. ; ^ )

Thank goodness for partners with backup guns. I’ve actually been writing about those, and your stories show how critical they can be. I hope your LT added one to his daily wear after those two events. If that had been me, I never would have been able to sneak up on anyone again, because all the extra hardware I’d be carrying would clink and clunk with every step. Anybody know where I can get a shoulder rig for a Thompson SMG? Hey, did you hear about Mike? He fell into a puddle and drowned because he had 125 pounds of spare ammo and guns on him, and couldn’t get up! ; ^ )

One hammer nose (firing pin) broke on a

brand new Model 66. At the range for

testing, fired one round and then click.

And click again. Dealer loaned me a

non stainless K-frame hammer which

worked fine until S&W could replace the

broken one.

I wondered if the broken firing pin was a

one-time fluke in production or if S&W

had a whole batch of defective pins.

Around the same time, my gun dealer also

found a brand new Smith revolver without

any barrel rifling.

This was in the early 1980s.

Hmm . . . sounds like the Bangor Punta or Lear Siegler days? Those were tough times for S&W quality control. That was good of the dealer to rescue you like that! Knock on wood, I’ve never broken one, but I also don’t shoot those guns nearly as much as some of you have/do.

This is a great article. If I had to pick any repeating centerfire handgun without being able to exam it or test it first, and the fate of the world depended upon it firing without fail for the first thousand or so rounds of quality factory ammo, I’d pick an unmodified .357 Ruger Blackhawk. I’ve seen them fail due to ammo problems, or light strikes after lightening the main spring; I’ve heard of them jamming due to a ‘poor man’s trigger job’ (unhooking one side of the trigger return spring). But unmodified, I don’t know of any failures to fire that weren’t due to poor quality ammunition. Don’t get me wrong – it’s a man-made mechanical device, so I’ve no doubt that there are many possible failure modes. But it’s interesting how many of the potential failures you list here are specific to double-action revolvers. The trade-off for faster reloads and a double-action trigger is increased surface for failure, the same trade-off for going from DA wheel gun to an auto.

I’m not getting rid of my DAs anytime soon, but this is a good reminder to keep them in good running order – their high reliability can still be compromised by operator errors.

You know, that’s a really great observation! I was definitely focused on DA revolvers when I wrote the article, but if I had to do a similar list for SA guns, it would be MUCH shorter. Something to think about, there. A stock Blackhawk is probably as safe a bet as you can make.

Maybe I’ve been lucky in that none of my DA revolvers has ever malfunctioned, but three of my Ruger single actions froze up. Two of them were brand new, the other had very low mileage. In all three cases, the culprit was the pawl.

All ended well with Ruger paying the freight to return the guns and quickly fixing two of them-the other was replaced with a new one–and they’ve been running reliably every since. This experience taught me that even highly regarded, supposedly very durable firearms can fail, sometimes right out of the box. But purchasing a firearm from a manufacturer with an excellent warranty and customer service department like Ruger’s provides great piece of mind.

An excellent point, Spencer. If it’s man-made, it can be flawed. I never trust any gun right out of the box.

Half asleep this morning when I wrote the comment above, and the last few words, “piece of mind” should have been “peace of mind”. However, I did give Ruger a ‘piece of [my] mind” during the single-action revolver warranty repairs!

That’s terrible! I’m glad Ruger made it right. I am curious, were those .44 or .45? Part of the reason I specified .357 in my hypothetical is that I’ve heard of more quality control issues with the larger bores on the Blackhawks (although outright not working is new to me).

Still, regardless of caliber, the timing ought to be near enough to perfect out of the box. I’m guessing buying the second one was tough, and you were flinching like crazy when putting money down on the third one.

Two were .44 Magnums and one a .22LR, Tyson. Given that they were built over a 40-year time period, it doesn’t appear the reason was a sudden drop in quality control, a change in design or a new manufacturing process.

My worst experience was a Single Ten .22LR; it was returned three times to the factory before it was replaced with a Single Six. The latter revolver has always run like a top but I suppose Ruger made sure it was reliable before shipping it to me.

In spite of these troubles, I really like my Ruger single actions and credit the company for its excellent customer service.

I was just shooting a brand new Ruger single action yesterday that had me impressed! More to follow.

Spencer, if it’s any comfort (or maybe not), the Single-Ten is a timing nightmare. It is more than just the increased number of ratchet contact points, but the size of the Single Six (or Ten) cylinder compared to its bigger counterpart, the 10 shot GP 100. The smaller you go in overall geometry, the more delicate (precarious) and precise the engineering has to be.

With the Single-Ten, instead of 60 degree contact points, its at 36 degrees of rotation – and I dare say that despite the rugged design of Ruger single actions, even the best gunsmiths would utter verbal insults causing sailors to blush.

Notwithstanding that issue, my .357 Blackhawk Convertible and my Super Single Six convertible always seem to end up in the range bag . . . ummm.

brand new s&w full lug 629 stainless broke main spring on second round .great hog pistol….finally

As always, Mike, great article. I carried a S&W model 19 my first five years as a police officer. I shot a lot, as I was single and had nothing else to do on my days off (Tuesday & Wednesday). My model 19 failed to fire once, I somehow forgot to put powder in one of my reload rounds. The armorer maintained the revolvers well. He fixed end shake on that gun a couple of times. I also had one misfire with my model 60 snubby. I pulled the trigger again and it fired. Turns out the hammer nose was cracked. The armorer replaced it with a blue one, that’s all he had, it’s still a reminder of that misfire to this day.

I still carry a revolver off duty and as a second gun on duty 30 + years later. I can live with two misfires in over three decades.

Keep up the good work!

Those are pretty good odds, BC—and one of those misfires still went bang the second time! I’ll take that kind of reliability any day. Thanks for writing in and sharing the data points!

After reading this article and the attending replies I went shooting. I always round out a session with a .22 revolver, in this cases a GP-100. After firing the the first 10 rds I reloaded with a Speed-Beez loader and the cylinder would not close. Unburnt powder under the extractor star. Yep, they can malfunction

A well-used ex-police S&W Model 13 .357 Mag began exhibiting lock-up issues. In rapid double-action dry firing the cylinder often spun past the next charge hole but always engaged the one following. After marking the cylinder with a grease pencil the malfunction became obvious, and it was repaired by a gunsmith.

Great article, Mike!

Now I know how much I really don’t know about my revolvers. Sigh. I did have a broken spring on a new-t0-me SP101. The previous owner had not shot it much. I kept thinking that the cylinder and ejector rod needed more lube because the cylinder wasn’t rotating. And… being a new shooter, I thought it was something that *I* was doing.

I had both of my Rugers deep-cleaned at the Gunsite Gunsmithy Shop (Finks Guns) this past year.

Thanks for sharing your knowledge, Mike.

WGJ

JUDY!!!! Great to see you here, again! Glad you got something out of the article.

The link you provided to Wolff Gunsprings seems bugged; if you try to click on any revolver brand name it leads to an error page that says 403 Forbidden – you don’t have permission to access this resource. Is this happening to anybody else?

Jeb, the link successfully takes you to their home page, but I experience the same problem you are having when I select the “Revolvers” tab, then try to select a manufacturer. I believe that’s a problem with their website. I’d use the phone number from the home page to make an order with them for revolver springs.

Mike

Another great article. You covered the bases pretty well.

The issue of spent cases under the extractor is more common than i would like, especially in snub guns with the shorter ejector rod. I’ve seen this aggravated on revolvers with improperly chamfered charge holes. Chamfering is best done with the extractor removed from the cylinder so the edges of the extractor are undamaged. To do itherwise induces poor extraction. Of course moon clips mitigate this problem.

Good article and excellent comments.

Thank you Sir! I appreciate you sharing the extra info about the effect of improper chamfering—that’s a helpful thing to know!

Great article.

I had the firing pin on a Rossi snub nose revolver break before I even had a chance to take it to the range.

I was practicing with it doing dry fire (using snap caps) and heard a strange noise and noticed the tip of the pin was gone.

This was about 10 years ago and the internet was full of Taurus customer service horror stories.

I called them up and explained the situation.

When the nice lady on the phone asked how many rounds I had fired and I replies “Zero” she sounded embarrassed.

I was sent a Fed Ex label via email and in 2 weeks the repaired revolver was back in my hands.

It had to take one more “Florida Vacation” when there was a recall on that model.

Once again the fine folks at Taurus covered freight both ways.

The wait was a little longer this time.

Understandable becase they had thousands of guns to go over.

I am glad Rossi is making revolvers again.

I hope they bring back the 2″ barrel like mine and I hope they go back to the polished finish.

I know matte stainless is more “tacticool” but I prefer the polished finish.

I love mine.

It is the smallest 6 shot .357 Magnum on the market and did not break the bank when I bought it.

It is in between a J and a K frame in size.

I jokingly call it a “lowercase k frame”.

This article is full of great advice and suggestions.

However there is one suggestion I refuse to comply with.

I will keep watching B movie Westerns until someone pries the remote control from my cold dead hands!

I watch them just for entertainment, not firearms instruction.

Lowercase K! I love it! Welcome aboard, Dr. Duke, glad to have you here.

The article about jams in revolver’s was informative. It made me wake up and be more particular to many associations I have with my wheelgun. Especially checking my primers. Not being a armor, I rely on my armor to check my weapons regularly. All I can do on a regularly basis is to keep it clean and not over oil. One thing I do, being a person who respects gun’s with cylenders, I watch utube videos regularly to see how others recomment preventive procedures. It’s better than nothing. Am I right or wrong? I had never heard of a primer going “pop”. It is hard to believe the amount of information in this article that some wheel gun owners do not know. Good article. Ned

You mention certain parts and spring replacement at “recommended intervals “ never seen this brought up or detailed on revolvers before ?!

Most of my guns are mid 1950’s guns shot a lot with all original parts including springs ( my most used 22 revolver a model 17 has over 100k through it )

Can you clarify or detail further what these replacement intervals should be?

While these days we take semi auto reliability for granted ( including feeding various hollow points) it wasn’t always that way

I still recall the days when a semi that ran HP reliable was considered a rare gem, and I think this is why you still hear the mythology of revolver reliability over the auto persist

I have seen and experienced nearly all the malfunctions you detailed!

Hi Daniel, I probably didn’t do a very good job of phrasing that, so thanks for the chance to address it.

With the autos, we have some routine replacement intervals for things like recoil springs, that are based on round count. That’s not the case for revolvers, generally.

With revolvers, the key is not replacement intervals, it’s inspection intervals. The typical semiauto shooter can easily replace things like recoil springs on a schedule, but you wouldn’t want the typical revolver shooter to go “under the hood.” That’s really the domain of a trained professional, who knows what he’s doing and what to look for. So, the key with revolvers is to make sure a trained set of eyes is evaluating the gun at an appropriate interval.

The recommendation from S&W for law enforcement agencies is that guns in service should be disassembled and inspected annually by a qualified armorer. The armorer will evaluate whether parts need to be corrected or replaced.

As you noted, most revolvers can run a long time without replacing springs and such, but any gun that is used hard or carried for defense should receive a periodic inspection. An annual inspection might be too much for the average revolver/shooter, but if you’re doing a lot of training with your gun, or if it’s regularly subjected to harsh conditions (sweat, fouling, environmental extremes, large volumes of high-pressure cartridges), then it wouldn’t be unreasonable.

Shooters who are attentive to preventive maintenance and know what warning signs to look for could certainly stretch the interval out, but it wouldn’t hurt to have an armorer look at your “duty gun” every five years, or so. That’s just a wag, not a manufacturer-recommended interval. Their lawyers would tell you annual inspections are the standard.

Hope that helps.