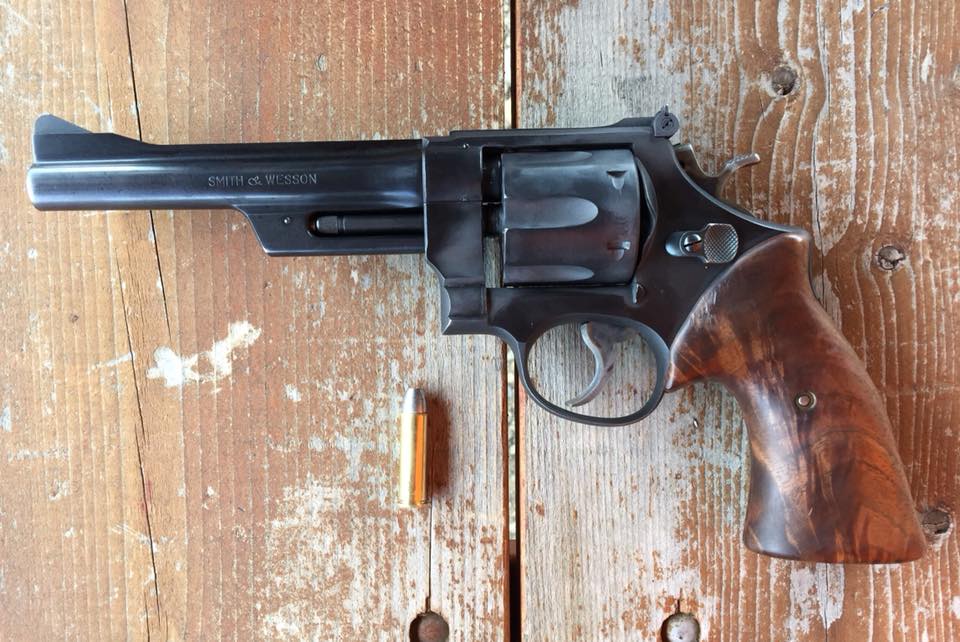

With a company history that dates back to 1852, Smith & Wesson has seen a lot of milestones and has delivered a host of classic designs to the shooting public. Some of those favorites have come and gone from the Smith & Wesson catalog over the years, but the ever-popular L-Frame family of revolvers remains, and continues to sell strong for the team from Springfield, Massachusetts.

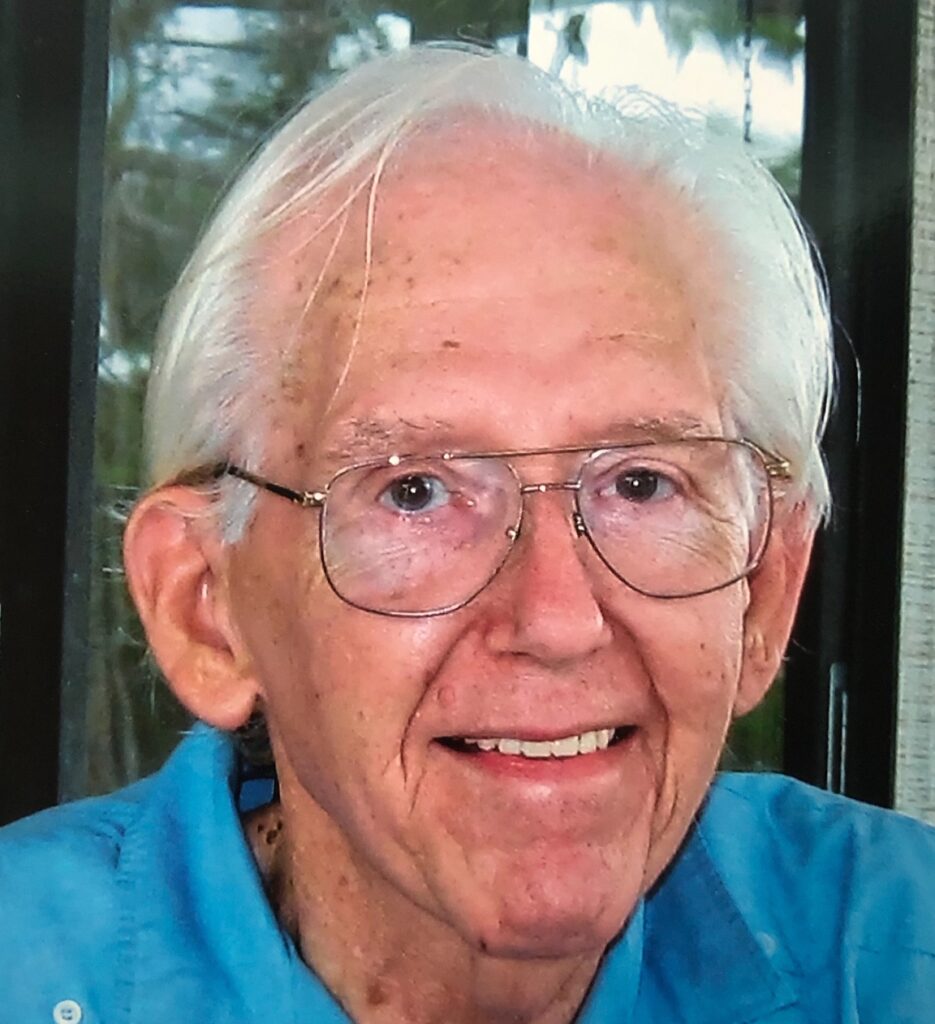

We’ve covered a bit of the L-Frame’s history before in the pages of RevolverGuy, but it’s time to take a deeper look at how this revolver design came about, and pay tribute to its creator, Mr. Dick Baker.

Origins

The beginning of our story starts with the early .38 Hand Ejector Model, which was the second of the solid frame, swinging cylinder guns produced by Smith & Wesson (the first being the .32 Hand Ejector, which barely preceded it). The .38 Hand Ejector went through several minor changes and eventually morphed into the legendary Model 10, in 1957, following a change to the hammer block mechanism in December of 1944, and the incorporation of a new “short action” hammer throw in February of 1948.

In these medium-frame, .38 S&W Special guns (“K-Frame,” in factory parlance, as opposed to the smaller “I-Frame,” designed around the .32 caliber), the barrel extension that poked through the frame and formed the forcing cone was slightly relieved at the 6 O’Clock position to make room for the swinging yoke and cylinder to close. This milled flat reduced the wall thickness of the barrel extension a slight amount, but did not create a structural problem at the low pressures of the .38 Special (which began its life as a blackpowder round, and only produced a SAAMI-spec, 18,300 psi maximum pressure), nor the later (1970s era) .38 Special +P round (21,500 psi maximum).

Magnum Era

We previously discussed in these pages how the legendary Border Patrolman, Bill Jordan, encouraged then-S&W President Carl Hellstrom to produce a K-Frame revolver chambered in the .357 Magnum cartridge during the Camp Perry, Ohio, National Matches in the summer of 1954. Prior to this date, the .357 Magnum had only been chambered in the much larger, N-Frame revolvers by Smith & Wesson, and it was Jordan’s wish to combine the cartridge’s legendary energy with the smaller and lighter K-Frame, to develop a powerful, yet compact, duty revolver.

Hellstrom and S&W made good on the deal, introducing the Combat Magnum in 1955. In order to make the combination work, they had to heat treat the barrel extension, and the svelte, K-Frame cylinder and frame to handle the greater pressures generated by the powerful .357 Magnum cartridge (37,800 psi, SAAMI maximum—more than twice the limit of the .38 Special that the K-Frame had originally been designed around).

The barrel flat at 6 O’Clock remained on the Combat Magnum, to allow room for the yoke to swing into the gun, as it did on the earlier .38 Special models. The more powerful .357 Magnum pressures threatened to damage and crack the thinner barrel wall in that spot, but the common practice of the day—encouraged by Jordan, himself—was to shoot a very limited amount of .357 Magnum ammunition in these guns, and do the majority of shooting with .38 Special ammunition. As a result, the early years of the Combat Magnum didn’t see any notable complaints about barrel cracking at the flat.

This would soon change, however.

Gas Rings

When a cartridge is fired in a revolver, a voluminous spray of high-pressure gas exits the end of the chamber and radiates out in a circle, parallel to the cylinder face. This gas contains lead and carbon particulates, which can accumulate and cause a buildup (as anyone who has ever cleaned a revolver can attest).

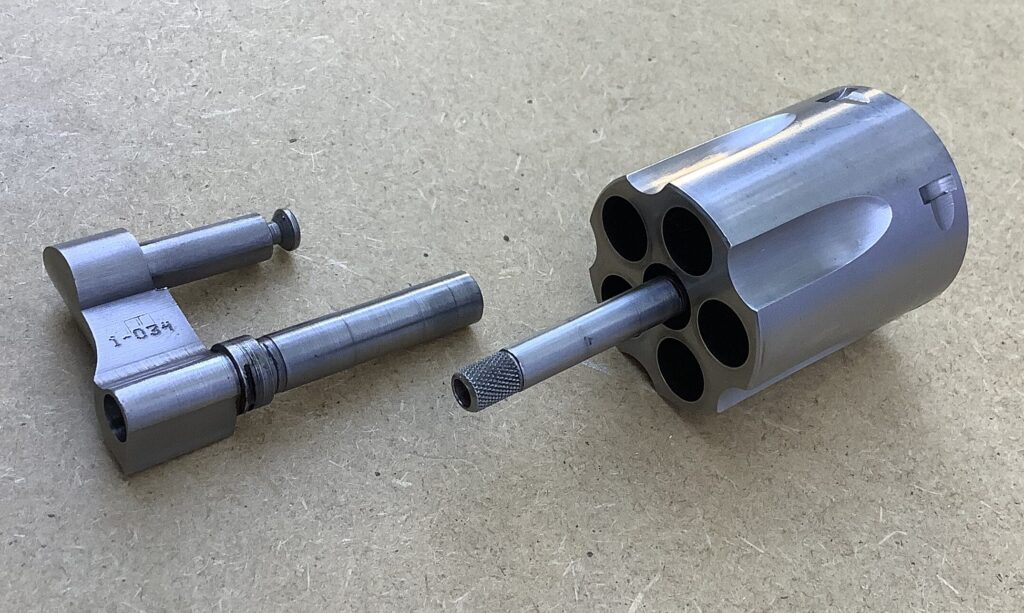

To prevent a buildup of contaminants on the axle that the cylinder spins on, revolvers incorporate a shield that we call the “gas ring.” The gas ring’s purpose is to prevent carbon and lead from building up between the axle (“arbor”) and the cylinder itself, which would impede the rotation of the cylinder.

The Combat Magnum (later designated the Model 19, in 1957) was originally built with the gas ring as part of the cylinder, as it had been since the .38 Hand Ejector was first built. Actually, the gas ring was pressed into the cylinder during assembly, but since it was not intended to be removed, it had always been considered to be part of the cylinder itself.

This state of affairs apparently lasted from the pre-19 era until sometime around 1974-1976, when S&W made a decision to move the gas ring to the yoke.

Why the change? When Senior Product Engineer Richard L. “Dick” Baker asked that question after arriving at S&W–from Ruger–in 1976, he was told that the gas rings had been coming loose on some guns (actually separating from the cylinder) and binding things up, so it was decided to make the gas ring part of the yoke in order to correct the problem. Others have speculated that heat-related, cylinder binding issues in the new (circa 1971), stainless steel versions of the Combat Magnum may also have encouraged the switch to a yoke-mounted gas ring.

Regardless of the reason, S&W moved the gas ring to the yoke during this era (somewhere in the middle of the Model 19-3 production, and the latter part of the no-dash Model 66 production—H/T the guys at the S&W Forum for figuring this out). With the ring removed, the cylinder face was now completely flat, and the axle (or “arbor,” or “barrel”) of the new yoke had a pair of grooves milled in the top that were designed to flow gases away from the tunnel in the cylinder that accepted the yoke, thereby preventing crud from entering the tunnel and building up between the cylinder and the yoke itself.

Interestingly, the switch to a yoke-mounted gas ring did not generate an engineering change number (commonly referred to as a “dash” number), which would frustrate S&W collectors in the future, as some 19-3 models (and some no-dash, Model 66s) would have cylinder-mounted gas rings, and others would have yoke-mounted gas rings. This situation may have even stretched into some early 19-4 and 66-1 models, since S&W would exhaust the supply of old parts before switching to the new ones—leaving some transitional guns with a mixed assortment of parts from different dash changes.

A flaw is born

The significance of the gas ring change, for our purposes, is that it drove a change to the barrel flat.

Dick Baker explained to RevolverGuy that moving the gas ring to the yoke changed the dimensions significantly enough that it was now necessary to remove even more material from the barrel flat than before, to make room for the modified yoke to swing in and out of the frame. This left a significantly-reduced amount of material at the bottom of the barrel extension, weakening what engineers like Baker called the “hoop strength” of the barrel extension.

Smith & Wesson didn’t realize it at the time, but they had just planted the seed that would later blossom into a big problem for the Magnum K-Frame.

More changes

Unfortunately, the move to a yoke-mounted gas ring created more problems than it solved.

It turned out that the yoke-mounted gas ring fouled more quickly than the cylinder-mounted gas ring. Users would complain about sluggish cylinder rotation after as few as a hundred rounds of ammunition (particularly if they were shooting unjacketed, soft lead bullets, which were very dirty). Additionally, the new design didn’t do anything to solve the problem of heat-related binding in the stainless models, because the problem was the steel itself. Stainless conducts heat differently, and has a tendency to heat and expand quickly, which could wreak havoc on guns with close tolerances. It would take a while for S&W and the rest of the industry to figure out how to deal with this issue, but moving the gas ring to the yoke was not the ticket.

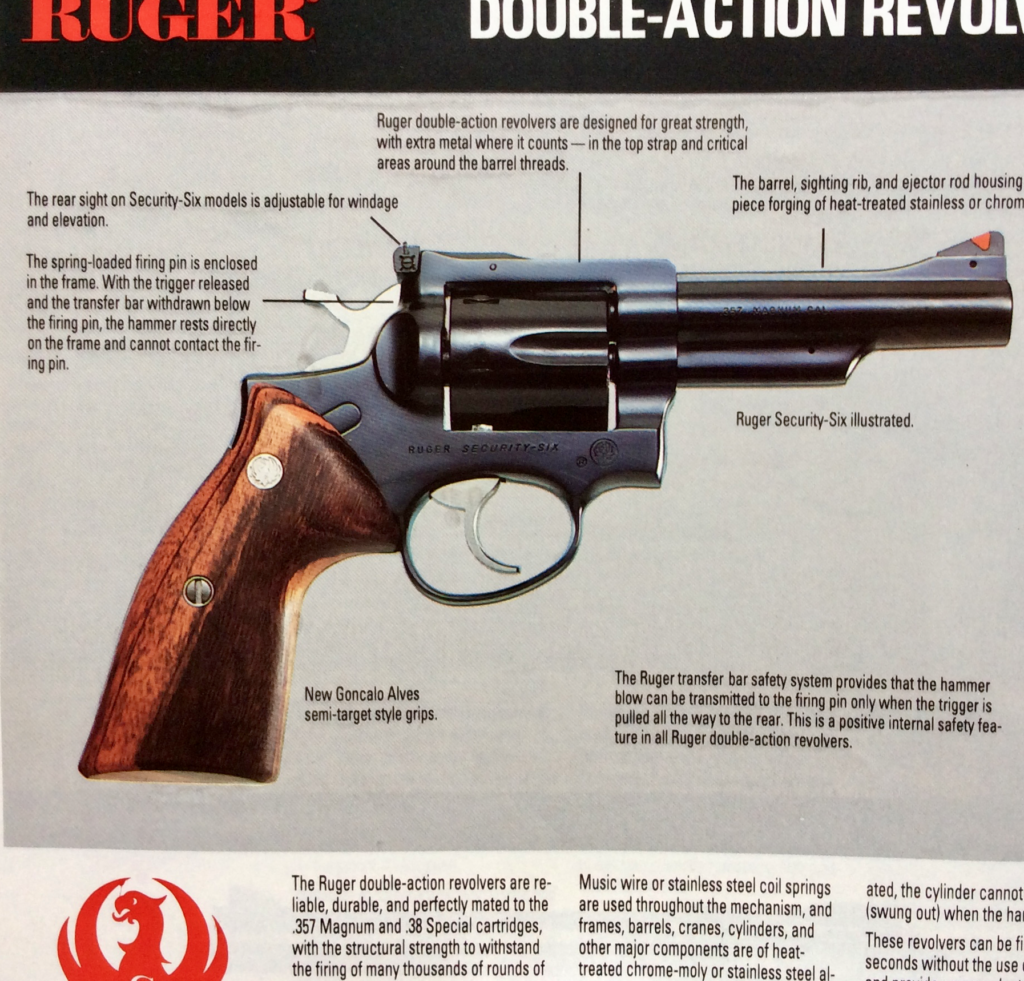

The problem with the yoke-mounted gas rings was no surprise to Springfield Engineering’s newest arrival, Baker. When he arrived at S&W in August 1976, Baker was puzzled to see the gas ring on the yoke, because he had just come from Ruger, where this kind of system (relief cuts on the arbor, to redirect/deflect gas) was already in use on the Six-series double action revolvers. Bill Ruger, Sr. was unsatisfied with the arrangement, due to the fouling issue, and had already directed Ruger engineers to correct this. In response, many law enforcement contract Sixes were built with gas rings on the cylinder (particularly for those agencies who issued the all-lead, .38 Special 158+P LSWCHP “FBI Load”), and the later SP/GP-series of revolvers that replaced the Sixes would be designed with cylinder-mounted rings as well.

Baker figured that he could design a better cylinder-mounted gas ring which would fix the problem of it coming off, and eliminate the fouling issue. He explained to RevolverGuy that, “I added an undercut in the cylinder recess for the ring, and swaged a new design gas ring (with internal belt) in place so it was locked in. It never came loose again and we eliminated the problem of fouling binding the cylinder.”

Unlike the previous switch, this modification generated an engineering change number. Collectors know it as engineering change 4 for the Model 19 (19-4) and engineering change 1 for the Model 66 (66-1). Jim Supica, in the Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson, properly dates this change to 1977 (“1977–Change gas ring from yoke to cylinder”).

Barrel flaw exposed

Baker fixed the gas ring issue, but the Magnum K-Frame’s barrel flaw persisted.

When the gas ring moved back to the cylinder with the 19-4 / 66-1 engineering change, Smith & Wesson did not return to the less aggressive cut on the barrel flat that pre-dated the yoke-mounted guns. Although it was no longer necessary to make extra room for the yoke-mounted gas ring, they continued to remove an excess of material from the 6 O’Clock position of the barrel extension. To explain, we can only presume that a certain amount of institutional inertia existed, and the company wasn’t nimble enough to abandon the recent production change and return to the old method, which left more material in place on the barrel flat.

It was about this time that S&W began to receive numerous complaints of cracked barrels in the 6 O’Clock area, and a number of warranty returns for the same.

For shooters, this problem first seemed to manifest itself as a difficulty in opening or closing the cylinder, since the barrel extension would flare slightly after being cracked, and bind on the yoke. Further examination would determine that the barrel extension had cracked, requiring a complete barrel change.

Why now?

The problem with K-Frame barrel cracks was obviously related to the thinner barrel wall that was an unfortunate leftover from the yoke-mounted gas ring, but there was another factor that contributed to the problem—a change in police training that had officers shooting more .357 Magnum ammunition in the guns than they used to.

Prior to the development of the K-Frame Magnums in the mid-1950s, the home for the .357 Magnum was the burly, .44/.45 caliber frames produced by S&W (Pre-27 and 27) and Colt (New Service). These large frame guns could easily handle the power of the standard 158 grain .357 Magnum loads that defined the caliber, and while they were quite powerful by the standards of the day, they were reasonably controllable.

When the svelte K-Frame was chambered for the .357 Magnum, those 158 grain loads produced a lot more felt recoil in the lighter gun, and the truth is that there were few shooters who were willing to do much shooting with the heavy-kicking ammunition in the Combat Magnum. Even Bill Jordan, the driving force behind the project, testified that the Combat Magnum was best viewed as a .38 Special that could shoot a limited diet of Magnums:

The K-Frame is perhaps a bit light to stand up under a steady diet of full charge .357 loads. Anyone wishing to do all his firing with maximum loads would do well to stick with the heavier frame of the original [N-Frame] .357 revolver.

This fit in neatly with the police training doctrine of the time, which encouraged officers to shoot low-powered target ammunition (particularly 148 grain, .38 Special wadcutters) during training and qualifications, then load up with more powerful 158 grain loads (in either .38 Special or .357 Magnum) for duty.

By the early 1970s though, there were a few trends which combined to change the landscape for ammunition.

First, the burgeoning “Officer Survival” movement of the era (encouraged by events like the LAPD Onion Field incident, the civil unrest and violent crime spikes of the mid-60s and early 70s, and disasters like the CHP’s Newhall Gunfight) changed the nature of police training, equipment, tactics and policies, and encouraged officers to shoot duty-equivalent loads during training and qualifications. It was now frowned upon, in the most progressive police training circles, to shoot light loads in training and carry heavier loads on the street—the expectation now was that officers who wanted to carry Magnum ammunition on duty should also train and qualify with it. After they got a taste of continuous shooting with the heavy, 158 grain Magnums in smaller guns like the popular Combat Magnum, they started looking for cartridges loaded with lighter bullets, which wouldn’t kick as much.

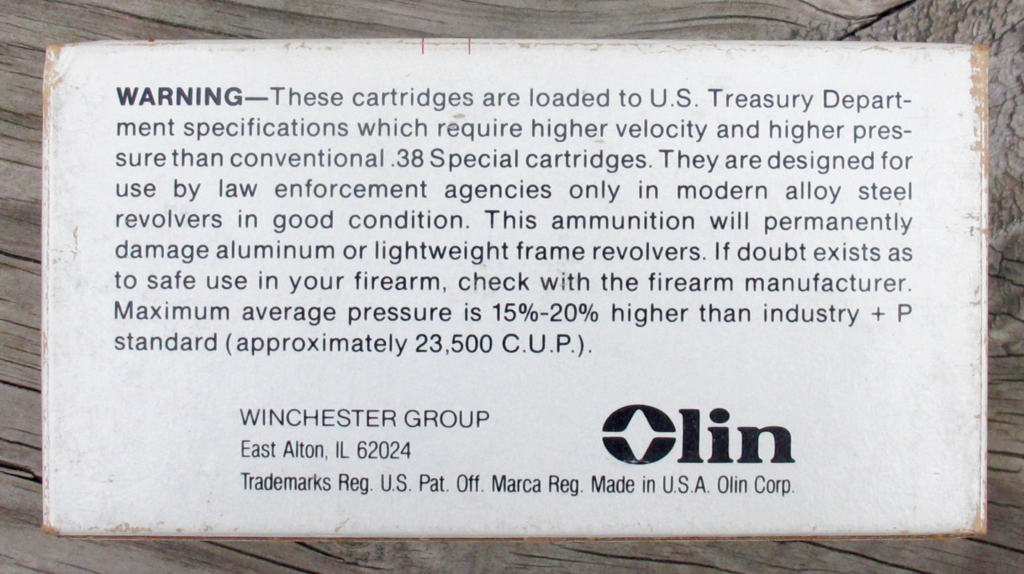

A second trend was the growing belief during this time that lightweight, high-speed projectiles were more effective loads for stopping violent opponents. This theory of “stopping power” was popularized by the National Institute of Justice’s (NIJ) Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA) project, which evaluated duty ammunition according to their newly-developed Relative Incapacitation Index (RII) model.

When the LEAA’s report on duty ammunition was published in 1975, the loads that earned the highest RII ratings featured high speed, lightweight, rapidly-expanding bullets. Loads like the traditional, 158 grain .357 Magnum did not perform as well in the LEAA test as the new generation of 110 and 125 grain bullets that were introduced circa-1965 by manufacturers like SuperVel, so these loads quickly gained favor with many police departments who were influenced by the LEAA study.

The intersection between officers looking for lighter-kicking Magnum loads to shoot in K-Frame size guns for training and qualification, and an authoritative source claiming that loads with lighter bullets made better “stoppers,” meant that there was a skyrocketing interest in the new 110 and 125 grain .357 Magnum loads at precisely the same time that S&W was aggressively milling the flat on the Model 19 and 66 handgun barrels.

This was problematic, not only because it encouraged officers to shoot more Magnum ammunition, but because the lighter 110 and 125 grain bullets might accelerate wear on the forcing cone.

The short and long of it

There’s a theory out there that shorter (lighter) bullets may allow more gas to bypass the bullet and enter into the bore ahead of it, causing more damage than you’d see with a longer (heavier) bullet.

When a longer bullet (like the 158 grain that was standard for the caliber) enters the forcing cone, the aft end of the bullet is still contained within the chamber throat of the cylinder, and has obturated to completely seal the ball end of the cylinder. This seal prevents gas from escaping past the bullet. By the time the tail end of the bullet clears the cylinder, the nose of the bullet has already started to seal the forcing cone and leade area, preventing a significant bypass of hot ignition gases. The surplus gas which does not follow and propel the bullet down the barrel is vented out the barrel-cylinder gap, to the sides.

With a shorter bullet, there’s a greater tendency for ignition gases to bypass the bullet and enter the forcing cone and barrel ahead of the bullet itself. This is because the barrel has not been sealed yet by the nose of the shorter bullet when the tail of the bullet clears the ball end of the cylinder. This allows more time for very hot, high-pressure ignition gases to bypass the bullet and enter into the bore ahead of the bullet, where they can cause increased damage.

We don’t have our own lab to test that here at RevolverGuy, but it seems like a logical explanation to us. One thing we are sure of, is that the propellant gases are different between heavy and light bullet loads, and these differences could account for accelerated fatigue in a barrel. As longtime industry veteran, Ed Harris explains:

Lighter bullet .38 Special +P+ (Treasury Load) and .357 Magnum loads, optimized for barrels shorter than 4 inches, are generally loaded with faster-burning, higher energy, double-based powders producing a higher flame temperature. With these powders, temperature and pressure peaks about the time the bullet is transitioning from the cylinder throat across the barrel-cylinder gap.

In contrast, Harris explains, heavy bullet loads use slower burning powders with deterrent coatings (to slow the burn). This changes the pressure and temperature curves, shifting them “forward,” so that the peak doesn’t occur until after the bullet has left the cylinder and entered the barrel.

As a result, the lighter bullet generates a gas which is is both hotter and at a higher pressure than the gas produced by a heavy bullet load. This potentially subjects the forcing cone and leade to more damaging gas than they would experience if a heavier bullet (with its slower burning powders) had been used.

problem child?

A former Smith & Wesson employee from the period puts an even finer point on the lightweight bullet issue, by pointing out that some brands were more problematic than others:

The biggest contributor to the K-Frame model 19/66 barrel splitting issue was the Winchester 125gr JHP .357 ammo. I split barrels with this ammo in as little as 11 shots on a new gun. It had very high and erratic pressures caused by the bullet sealant. Pull forces to move the bullet out of the case were up to 385 pounds! Pressures would be crazy with that high a bullet pull force. Spilt barrels would happen quickly with this ammo.

It’s hard to know if this was a persistent problem that stretched across many years, or just a spotty one that affected certain lots of ammunition, but it would help to explain some contemporary reports that hinted at inconsistencies across agencies, with some reporting high numbers of failures, while others encountered fewer.

perfect storm

Taking all this into account, it’s likely that the mechanism of injury for the cracked K-Frame barrels was a combination of the following:

-A weakened barrel extension, caused by the aggressive milling of a flat at the 6 O’Clock position (which was required for the models with yoke-mounted gas rings, but unnecessary—yet still continued–for later 19-4 / 66-1 models with cylinder-mounted gas rings), and;

-An increased use of high-pressure, .357 Magnum and .38 Special +P+ ammunition which placed more stress on the forcing cone than standard pressure .38 Special ammunition, and;

-An increased use of .357 Magnum ammunition loaded with lightweight (110 and 125 grain) projectiles, which exposed the forcing cone to greater amounts of high pressure / temperature blow-by gases, which caused accelerated wear on the forcing cone, and;

-Selected brands or lots of ammunition that were more prone to cause cracking, by virtue of their internal ballistics.

Warnings

Baker indicated that his first awareness of this barrel cracking problem was circa-1979 (about 3 years after the barrel flats grew larger), when S&W was conducting some endurance testing of the Model 66, using .357 Magnum ammunition. One of the test technicians encountered the “sticky yoke” condition on two of the test guns (unfortunately, Baker did not indicate how far into the test this was, or how many guns were in the test), and upon examination, they were found to have cracked barrels at 6 O’Clock.

After becoming aware of this issue in the Stainless Combat Magnum, Baker stated that he went to the Outside Repair Department at S&W, and, “inquired if they had ever seen cracked barrels in the (blued Model 19) K-Frames, and they said they had,” suggesting that the problem was linked to “hot handloads.”

They apparently didn’t fully understand the cause of the problem yet, but Baker knew it was an unacceptable situation, and set about to fix it, with the full support of management.

The super K

Baker began to design a new prototype that would fix the known issue by increasing the size of the frame and cylinder window, as necessary, to avoid having to make the flat cut on the barrel extension. He called his new, proof of concept prototype the “Super K”:

I first made a layout of the breech end of the barrel with no flat for hoop strength. I went down to Assembly and asked if there were any problems in assembling M19’s or M66’s, and the assemblers said, “yes, the cylinder is too close to the bottom of the frame window when trying to fit the cylinder stop and adjust the timing.” So, I went back to my prototype “Super K” layout and put in .003 or .004 more thousandths clearance for that area, which later proved an advantage in fitting Model L guns. The cylinder became larger working around the no-flat barrel breech.

Baker said that his goal was to use as many K-Frame parts as possible in the prototype “Super K.” The hammer had to be longer for the taller frame, and the hammer nose had to be shorter (because it was a shorter reach to the rear of the cylinder window, up there where the frame tapered), but he was able to keep many of the internals the same. He planned to use the same barrel, with slight modifications, such as a change in the location of the ejector rod cut, and the obvious elimination of the barrel flat which had caused all the difficulties.

Baker made the necessary drawings and the team settled on building 20 samples in blued steel. The drawings were sent down to the Model Shop, where Baker’s old friend, Norm Spencer (Baker’s partner from the .40 B&S cartridge project), and nine other model makers began to build the prototypes in cooperation with workers from the manufacturing floor.

As Spencer explained to RevolverGuy, “the gun was a regular K-Frame from the hammer stud down, so we had Manufacturing run about two dozen frames for us using production fixtures to do as much of the work as possible.” Once the common operations were complete, the Production workers hand-carried the incomplete frames to the Model Shop, where Spencer and the other model makers did the non-standard work required to turn them into “Super Ks.”

There were a lot of details to attend to, as Spencer explained:

We opened up the top strap an additional 0.118 inches, which allowed us to move the center pin hole up 0.059 inches as well, to accommodate the bigger cylinder. We did the firing pin hole and barrel hole in the shop, and built a special hammer, hammer nose, and yoke as well. I worked on the frames, and other guys worked on the cylinder—which was a lot of work—while others worked on the barrel, with its relocated ejector rod slot.

In a fun bit of RevolverGuy trivia, Spencer described how the S&W Model Shop got some help from an unexpected source during this project. “We needed a tap for the barrel hole in the frame,” said Spencer, “and Dick borrowed one from a friend of his at Colt.” The borrowed tap was for a Python frame, so the “Super K” frame got a Python-sized barrel hole, and the same thread pitch. “We were in competition with each other, of course,” said Spencer, “but the companies cooperated a lot more back then than people thought they did.”

The Model Shop produced the experimental guns—which were marked with an “X” prefix before the serial number—in less than a month, and Baker’s new hot rod was off to the races.

Super Feedback

Baker said the resulting prototypes looked “like a blued Model 19 at a glance,” and they were “sent upstairs to the Academy’s gun assembly class, to have John Contro evaluate them and fit the action. He found a couple small problems that I quickly fixed.”

The Super K prototypes (which later disappeared—Baker isn’t sure if any of them survived) were handed off to Marketing whiz Roy Jinks, who brought them to a big match. The guns were a big hit with the shooters, but Jinks decided that they looked too much like a Model 19, and deserved a unique look of their own, so he suggested that Baker should add a full lug barrel.

“I took a Dan Wesson and a Colt Python barrel, and used them as a guide,” said Baker:

However, to make it distinctive I put a slight curve at the top and bottom of the muzzle–put on by turning, so they were slightly spherical. They were distinctive and different. My thought on the curves was they were a distinctive shape, and would guide the muzzle into the holster without snagging, like the sharp edge on a Python muzzle would. I can’t believe it turned out to be a classic that is often imitated.

Model barrels were made from Baker’s new drawings, and they were an instant hit when everyone saw them. Management gave the go-ahead to start producing the new guns, which would be called the Distinguished Combat Magnum (adjustable sights version) and Distinguished Service Magnum (fixed sights version). The new, Medium-Large frame they were built on would be called the “L-Frame.”

New member of the family

Smith & Wesson started production in 1980 with the blued steel Models 586 (adjustable sights) and 581 (fixed sights), but Baker said, “interest in the gun quickly took off with the classic 686 in stainless steel.” A fixed-sight, stainless Model 681 was also produced.

The timing of the L-Frame couldn’t have been better. Smith & Wesson sales had slumped, and strong demand for the new L-Frame guns prevented layoffs during the recession of the early 1980s. Baker noted that, “the L-Frame is considered one of the top 10 winners in the history of S&W! Not too bad!”

Super K Revival?

The L-Frame reached its apex with the wildly popular Model 686, but there were a few other L-Frames that were interesting and worth mentioning, even if they were short-lived, or didn’t get into production at all.

Two great examples were the Models 619 and 620, which were introduced in 2005. By this time, the K-Frame Magnums had disappeared from the catalog, and they were already being missed by RevolverGuys who wanted a medium-frame .357 that weighed a little less than the 686, with its full lug barrel.

The 620 was as close to a modern incarnation of Baker’s Super K as you could get. For the 620, S&W hung a 5” barrel on the stainless L-Frame that looked like it came off a K-Frame Model 66, but its construction was very different. Instead of being forged from one piece, the half lug barrel on the 620 was actually made in two pieces, with a thin liner surrounded by a shroud. The barrel on the companion, fixed-sight, Model 619 was built similarly, but didn’t have an enclosed ejector rod. Instead, the 619s profile was reminiscent of the Heavy Barrel Model 65, with the tip of the unshrouded ejector rod locking up into a small lug, up front.

In a departure from the Super K, both the 619 and 620 had 7-shot cylinders, made possible by the larger cylinder in the L-Frame. Norman Spencer explains that, “the 7-shot cylinder is actually stronger than the original 6-shot,” because the cylinder stop slots on the cylinder are offset from the chambers, instead of directly on top of them, which creates a thicker and stronger chamber wall.

Neither of these guns lasted more than a year or two in the catalog, even though the lighter guns (about 3 ounces less) handled a little more nimbly than a 4” Model 686. Personally, I was fond of the 5” barrel length and the profile of these guns. As a traditionalist, I wasn’t super fond of the 7-shot cylinders and the two-piece barrels, but they weren’t deal-killers, and I would have eagerly bought one of each, had it not been for the infernal, internal lock that plagued these guns, like almost all post-2001 Smiths.

Some things just couldn’t be overlooked.

Skeeter Special?

Before he left S&W in 1986 to pursue other interests, Baker had a model maker build a 6-shot, L-Frame snubby chambered in .44 Special. It wasn’t an official project—it was just another one of those itches that he liked to scratch as a gun guy, like the .40 B&S he invented with Norm Spencer “during lunch hours.” The L-Frame cylinder didn’t leave a lot of room for 6 rounds of .44 Special, but Baker thought it might work because the .44 Special is not a hot round.

The .44 Special, L-Frame snubby idea didn’t go anywhere for the longest time, but S&W eventually took a whack at it with the Model 696, in 1996. The 696 had a round butt frame, a 3” full lug barrel, an external hammer, and a 5-shot cylinder. You can think of it as Smith & Wesson’s version of what Ruger recently accomplished with their GP100 in .44 Special, and it’s a shame this handsome gun only lasted in the catalog from 1996 to 2002, because it would probably be very competitive today with the Ruger product that reignited interest in this class of gun.

The unique Model 296Ti followed the Model 696 in 1999. While the 3” barrel of the 696 arguably took the medium-large-framed gun out of the snubby class, the 2.5” barrel on the Model 296Ti was definitely an attempt to qualify. The 296Ti featured a round butt, Centennial-style, aluminum alloy frame, with a 5-shot, .44 Special titanium cylinder. The frame looked more like a Bodyguard-style, with its distinctive humpback, but it was a closed, “hammerless” frame, and therefore marketed as an “Airlite Ti Centennial.“ The shrouded, two-piece barrel was marked for a maximum bullet weight of 200 grains.

The distinctive Model 296Ti wasn’t well-received and didn’t last long in the catalog. Neither did the companion Model 242Ti—a similar gun with a 7-shot, .38 Special cylinder, that disappeared even faster, after only a year. Other guns, like the Model 386Sc (a scandium alloy-framed, 7-shot, .357 Magnum with a titanium cylinder and 3.125″ barrel, which was also built in the PD trim package with a black finish and 2.5″ barrel) and Model 396Ti (an aluminum alloy-framed, 5-shot, .44 Special with a titanium cylinder and 3.2″ barrel) also came and went quickly in the early 2000s.

After a few years of quiet, the .44 caliber L-Frame concept was revived in 2014 as the Model 69 Combat Magnum—a 5-shot, .44 Magnum L-Frame with a 2.75” barrel.

This time, S&W was cooking with gas. The Model 69’s traditional looks appealed to consumers, as did the combination of .44 Magnum power in a Medium-Large frame. The Model 69 continues today in the catalog as one of only two L-Frames not chambered in .357 Magnum (the other being the Performance Center Model 986–a 7-shot, 9mm).

It’s hard to say if Dick’s early experimentation had anything to do with inspiring the current Model 69, but it did please him to see a successful, production, .44 caliber L-Frame in the catalog before he passed away.

great work

What pleased him most though was to see the resounding success of the L-Frame family, as a whole. Almost four decades after its introduction, the Model 686 is still one of Smith & Wesson’s best-selling revolvers, and one of the most-recognized revolver profiles ever.

It’s definitely a favorite here at RevolverGuy!

*****

The author would like to thank Dick Baker (R.I.P.), Dean Caputo, Ed Harris, Mark Humphreville, and Norman Spencer for their assistance with this article.

Excellent article, Mike! The detail on the factors that resulted in the perfect storm of K frame failures is appreciated. These issues should be considered by those shooting and carrying classic K frames today to keep them serviceable. Thank you for recognizing Mr. Baker’s wisdom and work, and the L frame that resulted.

Thanks Kevin! I’m glad you enjoyed the results of all the research!

Dick was truly a talented engineer and designer. I really regret that I didn’t spend more time talking to him about his work on the Trooper Mk.III action for Colt. Maybe I’ll still try to tackle that project someday.

And yes . . . we need to baby those beautiful K-Frames a bit! Gotta make ‘em last.

I own three classic Model 19s and a Model 65 (my father’s Idaho State Police revolver). I occasionally (a cylinder once a year) shoot 158 grain 357 Magnum loads, but predominately I shoot 38 Special; plain old lead round nose 38 Special.

Yes, great article. I have a nice 66-2 but only shoot .38s in it. I have shot 158 grain full power magnums in it and that is quite unpleasant.

I would add that in the old days a cracked forcing cone was no big deal since you just sent the gun to S&W and they installed a new barrel. Unfortunately they don’t make these one-piece barrels anymore, so if you crack the forcing cone on an older Combat Magnum you are out of luck, unless you can find a used barrel in good shape (the current Combat Magnums have redesigned two-piece barrels that don’t have the 6 o’clock cut, but they are not usable on the older 19’s and 66’s).

That’s an excellent point, Paul. Not only that, but it’s getting harder to find parts like hands, hammers, etc. We’ve been used to treating these guns like workhorses, but may need to switch gears a bit and start thinking about protecting and conserving them.

Mike, This is a great history of the L-Frame. After reading this, I realized that there was one other limited production .357 magnum L-frame that was almost a reinvention of, or close cousin to, Mr. Baker’s Super-K!

That was the 1998 issue of the 686+ Mountain Gun. It is a 7-shot, L-Frame in the typical mountain gun configuration with: adjustable sights, a one piece 4 inch tapered barrel, 3/4 length light weight ejector rod shroud instead of a full length underlug, a round grip frame, and NO internal lock.

If I ever decide to regularly carry a 4 inch revolver again, that 686+ Mountain Gun is the one I would probably pull out of the safe. With the right IWB holster (Fist #19 for me) I have comfortably carried while effectively concealing this gun for many a long, busy day. It shoots very well with any ammo I give it, and it is one that I will pass down to my children or grandchildren some day.

Regards,

Colt

Colt, I missed that one, and it sounds like a beauty! Enjoy that super six . . . um, seven-gun!

I gladly shoot .38 out of my prized model 13… it’s had a dozen or so magnums since I bought it, and probably no more, unless in a life or death situation. Would love to get a hold of an L frame, but the GP 100 will do! Great article Sir, thank you.

Thanks Riley! The GP is a heckuva gun, and you’re really not missing anything. That GP will stay in time forever!

One of your best yet !! Obvious a LOT of time and research went into this, and the result was a superb treatise.

The late and great Dick Baker was to the double action revolver what Paul Mauser was to the bolt action rifle. He saw serious flaws in the big picture of revolvers that went missing-in-action to most others.

Between his time at Colt, Ruger, and S&W, he left us with a legacy of some of the toughest, most durable DA revolvers ever made: The Colt Mk III/V; the Ruger Security Six series that would morph into the Redhawk, GP and SP series; and with S&W – the L frame.

The former U.S. Customs Service had special runs of the 686 made with round butt configuration – 4″ went to the uniforms and 3″ went to the plainclothes agents. The 3″ carried like a K frame, easy to conceal, and was a dream to shoot. When the 686 had its first mod done (change out of the hammer nose and recoil plate), it became the 686-1. All the USCS service guns will be marked 686-M.

Thank you Sir! You’re right—Dick had a special knack for fixing problems and creating excellent designs to fix them! The Customs guns are quite desired by collectors, I understand. I’ve never had my mitts on one.

The first L-Frame mod would be a good standalone piece. Thanks for the idea!

Mike

I always wondered why by much beloved 66-3 had that flat. Bought it in 1989 and during my first trip to the range a LEO told me to only feed it 38’s, which I have done almost exclusively. The action is so smooth it rivals my Python of the same vintage…… how can you not love a revolver?

Congratulations! Very detailed and informative article!

I´m a police officer in São Paulo, Brazil. My service gun is a Taurus .357 Magnum model 66, blued, 4-inch barrel, factory wooden grips. I prefer to keep the revolver due the constant troubles with the new Taurus .40 S&W pistols.

It was made in 1992. K-frame, gas ring on the cylinder and has no flat under the barrel entrance.

Our Police Department has few .357 Magnum revolvers (some are Taurus 65, fixed-sight model, recessed chambers, bought in the middle of 80´s), that was carried only by high-rank or special units officers in the end of 80´s and 90´s beggining. I got this gun due the retirement of this personnel.

Our issued ammo is CBC/Magtech 158 grain, both soft and hollow point. The gun becomes VERY hot after two or three cylinders, but I never had malfuncions or cracks.

In the last training, I spent 200 rounds of SJSP CBC/Magtech 158 grains. Indeed, the cylinder axis remained very dirty after the exercise – that not happen with .38 Special ammo.

Thanks to RevolverGuy to provide us with valuable information. Best wishes from Brazil!

Thank you for this excellent update from Brazil! We are very happy to hear from you and we’re glad you enjoyed the article!

I have some questions about the Magtech ammo:

1. Is soft point used for training only, or does it also get used for duty?

2. Do police officers in Sao Paolo get to choose if they will carry .357 Magnum ammo or .38 Special?

We wish you and your fellow officers the best. Be safe and thank you for writing!

Hello, Mike!

Answers:

1 – We have old lots of soft point ammo. At the time of purchasing, SP ammo was use for duty. Today, we are burning that ammo on training.

Soft point 158 grain ammo is very effective against vehicle bodies.

CBC/Magtech ammo made in 80´s and beggining of the 90´s had a serious problem of case cracking. Years ago, I worked with an confiscated S&W Highway Patrolman. It was impossible to reload using that ammo, because a hammer was needed to operate the extracting rod. The cases almost always cracked on the first shot. Fortunately, this problem is past.

2 – Yes, we can. The standard ammo for .38 Special is +P 158 grains, semi-jacketed hollow point.

There´s two police forces in each state: the Military (uniformed) police, that retired all revolvers (both .38 Special and .357 Magnum) from service in 2010, and the Civilian Police (investigative, that I´m a member), that has a more diversified armament.

Thank you Sir! Very interesting!

A very informative article, thank you.

I know I’m persona non grata here so this won’t see the light of day in your comment section, but I think your readers would appreciate an article on the law-enforcement-proprietary revolvers of the 70s and 80s: the Model 66s with the Treasury-badge sideplates and special serial numbers that were only sold to ATF; the 2.5-and 3-inch K-frames that were made for the FBI and DEA (the 3-inchers were so popular they ended up being sold to the public); the 3-inch Ruger Speed-Sixes that Ruger made around 10,000 of for the old INS and Postal Inspectors (factory barrel length was 2.75 inches); the CS-1, the Customs-proprietary 686; and the (in my mind) holy grail, the Model 68 which, to my knowledge, was only sold to the California Highway Patrol and the LAPD and was never offered to the public. I think a lot of your readers would be fascinated by the history of the revolvers used by the good guys. (If I remember right, Smith also made DAO Model 10s for NYPD back when their officers could only carry blued revolvers in DAO. Maybe some other big PDs had large special orders like that, too.)

I’m always glad to hear from our readers and happy you wrote in. I’m fascinated by many of those guns as well, but just haven’t been able to get my mitts on any of them, outside of the Model 68. If you have some of these guns and you’re offering to loan them . . . well, we need to talk! 😉

I don’t know if you saw our prior story on the Model 68, but I think it’s the best coverage available out there on this beautiful revolver:

https://revolverguy.com/missing-link-smith-wesson-model-68/

Unfortunately, I don’t have access to any of these guns; they were sold to Federal agencies for issue, and when the Federal Government switches to new guns they destroy the old ones, so I don’t know if any of these guns even exist anymore. The only exceptions may be the 3-inch Speed-Sixes that were bought by the Postal Inspectors; when the Postal Inspectors went to Beretta autos, individual inspectors were allowed to buy their old revolvers if they wanted to, because the guns weren’t owned by the G, they were owned by the U.S. Postal Service, which is a private corporation. The government is a fascinating place.

Indeed it is! I’ve always been disappointed the feebs take this route with their surplus guns. Makes no sense to me.

I know some CS1s went into the commercial chain when they were rejected by Customs. You see them pop up now and then, but I’ve never had my hands on one.

That’s neat info about the Postal Sixes! Thanks for educating me on that!

Great article Mike…..takes me back to 1988 when I started as an LEO and issued a Model 64. I miss that revolver a lot. I’m now retired after working 29 years and I still carry a revolver, though now it’s a LCR in .327 Federal Magnum.

Appreciate your experience and knowledge about wheel guns. I learned a lot reading it.

Many thanks Alan! Glad you’re still a RevolverGuy! That LCR in .327 Fed Mag is a great choice.

Thank you for directing me to your Model 68 article. It was fascinating and I don’t know how I missed it.

In addition to the history of the gun itself, I never knew before this that CHP had adopted the T-load for duty. I often wondered why a highway patrol, which, you know, patrols highways, didn’t carry .357s for their car-penetrating abilities, but the T-load out f a 6-inch barrel would be a pretty potent round.

The Treasury Load was a product of the times. The first class of female Traffic Officers graduated from the CHP Academy in 1974, and there were concerns about recoil, so Magnum ammo was dismissed as an option. The T-Load was a good choice for a .38 Special, but was still a shallow penetrator out of the 6” guns, because it was designed to be that way (good discussion on this in the recent L-Frame story on our blog, if you haven’t seen that yet). A Magnum load would have been better to get through cars, as you noted.

Does anyone have any information on my somewhat-mysterious M66-7? It does NOT have the barrel flat of the earlier K frames, but also does not have the two-piece barrel and modified lockup of the newer, post-2014 M66-8s. Do I need to avoid lighter, magnum loads, or is there no weakness here? Smith seems to have thought correction was still needed, or it wouldn’t have altered the barrel and lock-up, right? I’d appreciate any information or insight from revolverguys and gals.

Hi D, thanks for writing in! I have to admit that I wasn’t keeping up with the S&W line very much after the darned locks crept in, so I was unaware that the 66-7 version had a full barrel hoop, without the flat. If you’ve got a full-profile barrel hoop, then you can certainly shoot a reasonable amount of magnum ammunition. I wouldn’t do ALL of my shooting with magnums, because it’s still a medium-frame gun and you don’t want to beat it up too much (create an endshake or timing problem), but I wouldn’t be worried about barrel cracking with a full-hoop barrel. Hope that helps?

This is an absolute amazing article with the type of information and details rarely seen in the mainstream firearms media. Outstanding job Mike.

Thank you Sir! Great praise, coming from you. Appreciate it.

Wow, amazing background details on the development of the L frame. Nicely written, and we are soooo glad you were acquainted with Mr. Baker. This was pure enjoyment!

Glad you enjoyed it, Erick! We’ve got another L-Frame story that will publish soon—“the rest of the story,” as they say.

Thank you for the article. I think the L-Frame is an excellent size for a duty/fighting revolver if one is seeking magnum power (for .38 Special, I think the K-Frame is sufficient).

I only own one L-Frame, a S&W 69 in .44 Magnum with the 4.25″ barrel. I haven’t gotten to shoot it as much as I’d like to thanks to 2020, but I love it. I think it’s really cool. Just wish there was a push-style speed loader available for it, but my 5-Star speed loaders for it work fine.

I hope you gentlemen are doing well, and have a pleasant holiday season.

Thank you sir! We appreciate the kind regards and your participation in the comments! I feel your pain about the lack of a good push speedloader for your gun . . . common gripe around these parts. That S&W 69 is a compelling gun—good sized package, plenty powerful for most anything in North America. Happy Thanksgiving!

Excellent article!

Back in 1982 I had the barrel extension split on my Model 19. The cylinder was turning with drag and I had to use a mallet to open it. I simply assumed that it was caused by hot ammo that was 125 JHP’s over a near max load of Green Dot. I sent it to S&W and they repaired it and charged me an arm and a leg for it which I accepted because I assumed it was my fault. I probably should be highly upset to find that they charged me to fix a known issue, but it was 40 years ago and no longer matters.

Thanks for this great article!

Thanks Charlie, glad you found it! I love your Bill The Cat logo! That was a great comic strip, back then.

Your article is exceptional!

Great work!

I am having trouble finding a holster that fits my S&W 686 L frame 6” barrel. I ordered a leather holster from a well known manufacturer, and couldn’t get the retention strap to snap, closed. Tried stretching it, to no avail. Any ideas?! Pls advs!

Thanks for your expertise and knowledge!

Thanks WG, glad you liked it!

Thumb breaks on new holsters are often very tight, and take a little work to close. I experienced that on the Galco Phoenix holster we tested here, for example:

Galco Phoenix Review

Those will self-correct, as the leather stretches, if you leave the gun snapped into the holster for a while.

I’m not sure which brand you have, but I’ve had good luck with L-Frame fits from Bianchi, DeSantis and Galco over the years, and would recommend them.

If you think your holster isn’t fitting right, I’d contact customer service for help. They should be able to get you squared away.

You don’t have an aftermarket hammer or a tall front sight interrupting the fit of the gun in the pouch, do you?

Well written, I have a number of revovlers by S&W and I am a retired LE Deputy. I caried a Model 19-5, I collect Model 1008, Model 10-10. et al. My son has a Model 19-5. Well written article. I switched back from polimer guns. Now with S&W revolvers I shoot Model 59’s AND sig 226. Also Beretta 92s. These I call quality. Keerp me informed. Ned

Glad you enjoyed the story, Ned. You might also like our two-part series on “The Great Frame Wars.” Thanks for reading and writing in.

I learned a lot from this article. After coming home on leave from Parris Island in January 1984, I bought a 6″ 686. Took it home to the farm, went out back and tried to fire it. After one or two shots..the cylinder would lock up tightly. Took it back to the gunshop, and they begrudgingly gave me another. Took it home..same thing only worse. Took IT back, and they thought I was up to something. He did give me another after saying something along the lines of “this will be the last one”. Well, this one worked and I shot it for years. Many many years later I came upon a recall for these guns for undersized chamber holes, then I finally knew what was wrong with the first two I had!

Thanks Robert. To clarify, the recall (which we wrote about, here) was not for undersize chambers, but for a firing pin bushing with a bore that was too generous, and allowed primer material to flow back into the channel. This is probably what you were experiencing.

This was the best explanation of the gas ring change on the Smith and Wesson revolvers that I found online. Thank you for putting this together.

Glad it was helpful, Bob!

I just bought a MD State Police commemorative 19-5 that has never been shot, do you know if they reverted back to a less aggressive cut in the forcing cone after going back to the cylinder mounted gas ring?

I addressed that in the story, Zach. They did not.