We’ve been talking a lot lately about the tremendous surge in demand for guns and ammunition, that began in the Spring of 2020. It’s the biggest gun story of the past year, and it certainly affects all of us as consumers of guns and ammunition.

The “Great Gun Crisis of 2020-2021” has dramatically increased the ranks of gun owners in America, and has simultaneously introduced many people to revolvers for the very first time. Whether they’re first-time gun owners, or seasoned gun owners who just bought their very first revolver, a lot of Americans are taking their first steps as RevolverGuys (which I use generically, to include all you RevolverGals out there) and discovering the joys of these great guns.

One of our readers recently suggested that these revolver newbies could benefit from some general tips and advice on how to handle and operate these guns. We’ve certainly done lots of instructional articles at RevolverGuy about how to safely grasp, hold, unload, function check, reload (here, here, here, here, and here), decock, and dry practice with your revolvers, for example, but I liked this idea of doing a more general, “Revolver 101” article that would collect some of the bits and pieces about handling and working with revolvers that don’t fit neatly into other categories.

So, without further delay, here’s some thoughts on various revolver dos and don’ts for our newest, revolver-totin’ brothers and sisters.

Flipping me off

Our first stop on this journey is a pet peeve of mine, and of every other serious RevolverGuy—flipping the cylinder shut on a double action revolver.

You’ve seen this maneuver before on TV. The character is holding a double action revolver with the cylinder open, and he decides it’s time to close it up. Instead of just pushing the cylinder into the window, like he should, he rapidly flips the revolver onto its side, so the heavy cylinder slams shut with great drama . . . and stupidity.

DO NOT DO THIS to your revolver! It’s a great way to damage your revolver, and it’s the mark of a rank amateur. So is the inverse–holding the cylinder release, and flipping the cylinder open with a flick of the wrist.

These maneuvers can damage the crane or yoke of your revolver, the cylinder stop, the ejector rod center pin, and other important parts, so please, please, PLEASE, don’t do this. As RevolverGuy Darryl Bolke likes to say, “every time you do that, a puppy dies.”

Wheel of misfortune

The kissing cousin of the flip maneuver is slapping the cylinder shut, often with the intent to have the cylinder still spinning when it closes into the frame.

This is just as dumb a maneuver as the flip, and possibly more damaging. If the cylinder is spinning ‘round when it’s closed into the frame, the cylinder stop will take a beating and the stop notches on the cylinder will probably get peened and damaged. You might also damage the yoke, center pin, and other parts. There are few ways you can destroy the delicate timing on your revolver more quickly than slamming the cylinder into the frame with a flip or a slap.

This is simple: When you close the cylinder on a double action revolver, you don’t want the cylinder to be spinning, and you don’t want to use excessive force. It can roll under the control of your thumb as it closes, but you don’t want it spinning. You can be firm and deliberate without being abusive, and it will make your revolver last much longer.

Horse before cart

Revolver Great Jerry Miculek reminds us that it’s also important to get the sequence right, when you’re opening your double action revolver.

Jerry advises that you don’t want to press on the side of the cylinder before you operate the cylinder release, because you could damage the center pin and the frame of your Smith & Wesson revolver. In normal operation, pushing the cylinder release forward compresses the center pin into the shaft of the extractor, and frees the cylinder to swing out of the frame. However, if the cylinder is already being pushed out of the frame when you operate the cylinder release, the cylinder may move before the center pin is fully retracted, and it may strike and drag on the edge of the hole in the frame, possibly damaging it. So, operate the cylinder release first, then push the cylinder out to avoid this.

A similar concern exists for the Colt lockup. In the Colt system, the cylinder is locked by a bolt that extends from inside the frame, into a recess in the center of the extractor. In normal use, the Colt cylinder release is pulled to the rear, which retracts the bolt from the extractor, and frees the cylinder to swing out. If you are pushing on the side of the Colt cylinder before the cylinder release is operated, you could damage the side of the bolt, or the edge of the recess in the extractor. So, once again, operate the cylinder release first, then push the cylinder out.

Single action sins and spins

Single action revolvers don’t have swing-out cylinders, but that doesn’t make them immune to being damaged by a careless handler.

One stupid move that you’ve probably seen on TV is to wind up and give the unlocked cylinder a spin, like you’re trying to pull start a lawn mower. With a loud buzzing sound, the cylinder whirs round and round, like a spinning game wheel, until it slowly runs out of steam, and comes to an exhausted halt with a click, click . . . click.

Congratulations, you just abused the delicate parts on your gun. The only thing you could have done to make it worse is to slam the loading gate shut, or cock the hammer to full cock while the cylinder was spinning round like a roulette wheel–that would have completed the injury.

Use some care and deliberation when you rotate your single action cylinder for loading or unloading, and don’t try to spin it rapidly for effect, OK? There’s no reason to do it, and it’s not cool, it’s just silly.

If you want to go the extra mile, and look like a real savvy RevolverGuy, try to line up the notch on the cylinder so that the stop falls directly into place when you close the loading gate—that will save it from having to drag on the cylinder and the raceway leading up to the notch, before the cylinder locks up. That’s a pro’s move, there.

Hitting the fan

Another single action sin (that unthinking people sometimes attempt on double action guns, too) is to hold the trigger back and rapidly “fan” the hammer spur with your support hand, like all those celluloid heroes on the big screen. This move always looks great in the movies, and delivers surefire results against hordes of baddies, but in real life, you’re just wasting ammo and damaging your gun (not to mention your hand—more than one person has cut themselves on a sharp edge, or pinched their hand, when attempting this move).

When you slam a hammer back into full cock, on either a single action or double action revolver, you start the cylinder turning fast, and it builds up a lot of rotational inertia. All that mass comes to an abrupt halt when the cylinder locks up, and it causes a lot of stress on the stop and the stop notches on the cylinder (seeing any trends, here?). It’s also not great on the surfaces where the sear and hammer make contact with each other.

Therefore, it’s far better to cock a revolver to single action with a smooth, steady, and slow draw of the hammer, than to slam it back with a rapid, jerky motion, as you do when you cock it too quickly or fan the hammer spur. Take it easy when you cock that thumb buster, partner!

Rimfire dry fire

We love our rimfire revolvers here, and we want them to last a long time, so we try to limit the amount of dry fire that we do with them.

On a rimfire, the firing pin strikes the rim of the cartridge near its edge, instead of in the center of the cartridge’s head (hence, the label “rimfire,” as opposed to “centerfire”). The collapsing brass rim of the cartridge actually cushions the tip of the firing pin when it strikes the cartridge, thereby protecting the pin.

If you dry fire your rimfire revolver with nothing in the chamber, the firing pin can strike the narrow shelf inside the chamber that the rim of your cartridge rests against, when it’s fully chambered. This can deliver a real shock to the firing pin, when the steel tip of the pin slams into the steel shelf in the chamber, and it can cause it to chip or break. It can also disfigure the shelf inside your chamber, and possibly peen it badly enough that it will prevent your cartridge from being easily chambered.

In centerfire revolvers, we often use snap caps to help cushion the fall of the firing pin, and preserve the health of our revolver as we safely conduct our dry practice. However, there aren’t many good snap cap options for rimfire guns. Some of the products on the market are good for “action proving,” which means you can use them to practice loading and unloading the gun, but they aren’t really designed to withstand many impacts from the firing pin in dry fire. Others are robust enough that they’ll withstand regular strikes, but it’s not clear how much protection they offer to the firing pin itself. They’ll protect the chamber, but not necessarily the firing pin.

An economical way to resolve this dilemma is to visit your hardware store and buy a package of plastic, #4 drywall anchors. These are typically yellow in color, and about 7/8” long, and they fit the chambers of .22 caliber rimfire revolvers just dandy. Because they’re plastic, they’ll cushion the firing pin tip nicely, while protecting the chamber. The yellow color will also help to identify them as training tools for safe dry practice.

You’ll chew up the plastic rims with repeat strikes, so you’ll want to rotate them periodically for best effect, and will need to toss them if the rim gets too ratty, or looks like it’s going to separate. When you’re done with your practice, you’ll also want to check the chambers and bore of your gun very carefully, to make sure that you don’t have any stray pieces of the drywall anchor left behind.

With regular use, however, they’ll help to keep your skills sharp and your revolver in good working order. We highly recommend the use of snap caps in both your centerfire and your rimfire revolvers, and think the drywall anchors are a super option for the latter. Give them a try and let us know what you think.

Keep it clean

A thorough treatment of the task of cleaning your revolver is beyond the scope of this article, and we’ll probably tackle it as a standalone piece sometime soon, but you need to keep your revolver clean to keep it working efficiently.

Your owner’s manual will be a good place to start on this, but those are notoriously brief about maintenance responsibilities. Every brand/model will have its own unique requirements, but here’s some general areas of concern for all revolvers:

• Keep the cylinder face and forcing cone area clean, to avoid cylinder drag and binding;

• Keep the area under the extractor clean, so it can sit flush in the cylinder. Debris that builds up under the extractor, like unburned powder grains, can prevent you from closing the cylinder, or create significant cylinder drag;

• Keep the ratchet clean, for proper operation;

• Keep the chambers clean, to avoid issues with sticky case extraction or rounds that won’t seat fully in the chamber by gravity;

• If you have a revolver with an external hammer, keep the hammer channel clean, to avoid the hammer or action binding on debris like balls of pocket lint;

• Take the grips off when you clean, to prevent rust from building up underneath them.

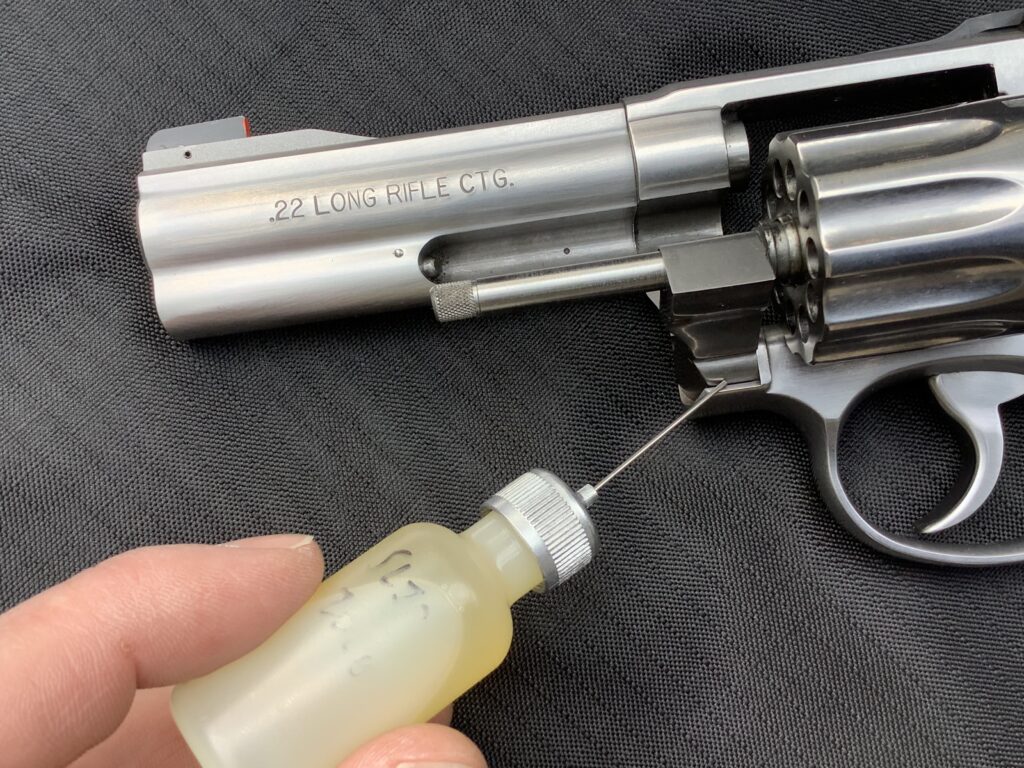

Lube job

Keeping your revolver properly lubricated is equally as important as keeping It clean. A revolver that’s dry will usually work fine, but a revolver that’s lubricated too heavily will collect debris that can jam the action, and may risk contaminating the ammunition, so be sparing with how much lubricant you apply, and be exacting about where you apply it. Refer to your owner’s manual for guidance.

Some places on your revolver that will generally need occasional lubrication include:

That’s a wrap

So, that’s a pretty good roundup of dos and don’ts to get you budding revolver enthusiasts started off on the right foot.

It’s certain that I forgot something good, so I’m going to rely on my fellow RevolverGuys to keep me honest, and add their own tips and advice in the comments section, below. Make sure you check those out, to learn from our esteemed RevolverGuy brothers and sisters, and be sure to let us know if you have any questions, either by using the comments section or by reaching out via the Contact Us tab.

Shoot straight and be safe out there!

Great points, Mike.

Well written, well done.

Many thanks! Hope it will be a useful reference for folks.

Unfortunately, this is very basic but sound advice that has to be frequently repeated in the gun world. (Thanks Hollywood!)

It’s also one of the main reasons why I won’t allow anyone to handle my firearms. A hard lesson learned long ago.

Oooh, I’ve had a disappointing experience with that too. I really didn’t expect it. It is indeed a lesson to learn!

Indeed. I recently watched a close friend flip the cylinder closed on my Model 27. We had a… discussion. Thanks for posting this, good info!

Hmm, I bet the discussion was very directive!

I have been reading your articles for a long time now, many thanks for this one. Great review of the basic revolver handing items and I really like the care and maintenance portion with the photos. Again, another great article. Keep up the great work.

Thank you Sir, it’s great to see you here in the comments!

Thank you for another great article, an oiler with a needle would be an excellent addition to my toolbox.

I’d been doing without for ages, and when I finally got some, I couldn’t believe it took me so long. They’re really great!

I had to be taught some of this when I got my first revolver! I didn’t have instruction growing up, and revolvers were less common in my limited circle of gun friends, so there was no way to find out until friendly folks online told me. Thank you for giving the same benefit to other newbies, it really makes a difference.

You betcha! I wish we could have gotten to you sooner! ; ^ )

Are there any other lessons that you wished you would have known, back then? Did we miss anything, here?

Haha, oh, I couldn’t say, I am still learning. I have the basics now, thanks to you and those on Reddit or the Cast Boolits forum, but I feel like every time I get confident I get too big for my britches and the Lord sends me a humbling lesson to remind me of what I don’t know or can’t do. I have been shooting exclusively home-cast and powdercoated bullets for over a year and a half, for instance, but only last week did I realize that my seating die was to blame for some of the shaving issues that I had endured, not my flaring die. I had so confidently purchased a Lyman M-die, just sure that would be the cure for everything… nope! Only after I had failed to address the problem by making assumptions did I actually put on my thinking cap and properly analyze the problem.

Long story short, I will be grateful to you for any wisdom you are pleased to share!

Well, we’re all still learning here, and we’re fortunate that we have lots of smart folks in our RevolverGuy community to help out. We’ll keep cranking out the articles if you keep reading and commenting.

Any other lessons I wish I’d known then (but learned the hard way) ??

Yeah — never date sisters

Haha! Maybe I should have specified, “Any other revolver lessons?” ; ^ )

Yeah, well . . . the smart ‘a’ in me couldn’t resist. On a serious note; however, with Colt revolvers, the way the cylinder is released is a feature that I learned to capitalize on when using my old formerly owned Colts (Pythons, Mk III and Mk V Troopers) in competition where speedy reloading was on the menu.

So, you’ve shot the gun dry and while maintaining shooting grip, with your dominant thumb, pull back on the release latch, and roll the gun to the left. Gravity will (usually) drop that cylinder right out into your non dominant hand. With the S&W and Ruger revolvers, you’ll nearly always have to give the cylinder a good nudge because of the two locking points (as opposed to one for the Colt) . . . .

Whereupon, thou cans’t grab said cylinder, turn the revolver muzzle up, and punch out the spent cases. While you have the cylinder in your non-dominant hand – and in control of the cylinder, bring the speed loader into play, drop the new rounds in, and resume dominant hand grip AND, hold back on the cylinder latch as you press the cylinder back in place ( oh, and yeah, release the latch when done ).

Sounds complicated, but it made for exceptionally fast load times. Alas, the Mk V Trooper – the strongest and best double action revolver Colt ever built ( in my not so humble opinion ) is gone, but not forgotten (unlike the easily forgettable Pythons)

Appreciate that very much Stuart, especially the part about holding the latch back when closing the cylinder—that’s something I haven’t done, and I’ll have to give it a whirl!

Good points to bring up, Mike. It seems like the majority of the population, even those within the “gun culture”, have not been taught the proper handling of revolvers. Enough so that it pays to give a crash course of good handling practices before relinquishing custody of a cherished revolver to an uninformed associate. Someone damaging an irreplaceable old gun tends to put a damper on relationships with us revolver folk!

Would anyone here object if this article were included with all new firearms owners’ manuals?

Ha! Could I get a nickel for each one? I might be able to afford a box of 50 wadcutters, that way!

Good advice on cleaning… back in my armored car days we were issued S&W 64s… a stainless steel .38. We had one guy carry one so dirty it almost looked blued. When I suggested he clean it the fellow laughed it off, stating “it runs better this way! The carbon keeps it lubed up!”!! Still wondering what snappy comeback I could have used. More seriously, Grant Cunningham writes some pretty good books on care and use, though titles escape me right now. I’ve found his books on Amazon.

Grant is indeed an excellent writer, and we’ve recommended his books for a long time. His book, Defensive Revolver Fundamentals is really super for wheelgunners, and his Protect Yourself with a Snub Revolver book is also good. I also liked the Defensive Pistol Fundamentals book.

Sounds like that armored car guard had enough carbon on his Model 64 that he could have used it as a pencil!

Yes, it was pretty bad!

My Brother had a Taurus PT-22 (yeah, I know….a bottom feeder….) handed down to him, never been fired. He was looking foe some snap caps, I told him about the Home Depot drywall snap caps. Well, 5 snaps later…..the firing pin snapped. I think that probably had more to do with Taurus’s QC than with Home Depots snap cap QC……

Mike: Another excellent set of reminders for us.

Most of my friends who I would let handle my revolvers or pistols are pretty “gun Savvy.” So the mishandling of revolvers is a faint possibility. However, on a couple of occasions over the years I have shown a double action revolver to someone who to my horror immediately flips the cylinder shut. I has taken great restraint on my part not to verbally scold them but to inform them of the hazards of such Hollywood inspired acts.

Working at a gun shop, had a few occasions when a customer would flip the cylinder closed (I usually handed it to them open), whereupon I would diplomatically explain how stupid such gun handling is; also would emphasize there would be a function check of the gun, and if it was damaged, they just bought it.

As to ‘fanning’, my first SA revawver was a Sauer & Sohn (Son?) .22 that Mom had to buy for me. It got fanned a lot early on, until I had to search for a replacement action spring. The gentleman who happened to have a Colt spring that worked gave me a diplomatic lecture on the stupidity of such gun handling, so I learned–and got a little embarrassed in front of the other guys in the store. I can say, even when fanning that gun, it was always accurate; every time I fired it, I hit…..something. Ace

Haha! Always great to hear from you, Ace! I got a really good chuckle out of that last bit!

I like the “you broke it, you bought it” policy . . . that’s good stuff. That would certainly teach a lasting lesson. I never worked the gun counter, but I catch all those same guys when I’m working at the gun club, and they don’t get any smarter between the store and the range. Oh, the things we see, eh?