Part II—Details and features of the Lipsey’s – Smith & Wesson “Ultimate Carry” J-Frames.

Welcome back go our comprehensive coverage of the Lipsey’s – Smith & Wesson “Ultimate Carry” (UC) J-Frames! In Part I of this series, we discussed the development of these new revolvers, and covered some of the features that make them unique, but the guns deserve a more detailed examination, so let’s dive into that now.

TWO CALIBERS

The first place to start is with the two UC chamberings–the .38 Special, and the .32 H&R Magnum.

The .38 Special is the classic J-Frame chambering, and needs little introduction and no justification. Dating back to the black powder era of metallic cartridges, the .38 Special is the longest serving of all the popular, modern service cartridges, having been introduced around four years prior to the 9mm, six years prior to the .45 ACP, 36 years prior to the .357 Magnum, 84 years prior to the 10mm, and 91 years prior to the .40 S&W.

While it dominated the American law enforcement scene for the better part of the Twentieth Century, the .38 Special is now most commonly encountered as a sporting cartridge, and as a defensive cartridge in small frame revolvers like the Smith & Wesson J-Frames. When Lipsey’s first approached Smith & Wesson about the UC project, there was no need to specify what the first chambering would be, as it simply had to be the .38 Special–the baseline standard for the entire breed.

The .32 caliber alternative was a different story. Smith & Wesson had a long history of manufacturing .32 caliber, small frame revolvers that dated back to the company’s origins, but the caliber had disappeared from the domestic catalog by the mid-to-late 2000s.1 Smith & Wesson had left the .32s behind.

Smith & Wesson’s Handgun Product Manager, Andrew Gore, was supportive when Lipsey’s Vice President Jason Cloessner approached him with the request to add a set of .32 caliber guns to the UC project in May of 2023, but there were probably some puzzled faces at Smith & Wesson when Andrew drafted the build sheet for them and created the SKUs. A purchase order for 2,000 units (which doubled by mid-week of the 2024 SHOT Show) was enough to satisfy curiosities though, and to get Smith & Wesson back into the .32 game, after a long hiatus.2

HEAD TILT

While the .32 caliber snubs enjoyed a healthy cult following during their absence from the Smith & Wesson catalog, and Smith & Wesson was happy to build the guns if Lipsey’s wanted to buy them, the addition of the .32 H&R Magnum to the UC project certainly caught some folks off guard.

By January 2024, the .32 H&R Magnum cartridge had nearly been relegated to the dust bin of ammunition history, alongside such efforts as the .357 Maximum, .356 TSW, .41 AE, and .45 GAP. Hardly any manufacturers were currently producing a double action gun in the caliber (perhaps only Charter Arms?), and ammunition manufacturers had relegated it to third or fourth-tier production status. The faithful minority of .32 H&R fans had grown accustomed to rolling their own, because factory production was so anemic and intermittent.3

So, there was a quiet skepticism, and a little confusion, in some corners of the market and industry when the Lipsey’s “Ultimate Carry” J-Frame was first introduced, in the days leading up to SHOT Show 2024. The .38 Special made sense, but why would Lipsey’s and Smith & Wesson chamber their hot new gun for a nearly-dead cartridge? 4

WHY THE .32?

There were a lot of reasons, actually.

The most significant attraction of the .32 H&R Magnum is that it doesn’t recoil like a .38 Special does. While there’s truly something special about the Special, especially in a small-frame revolver, there’s no getting around the fact that the combination generates a substantial amount of felt recoil with most flavors of ammunition. Standard pressure loads in the common 130 and 158 grain bullet weights generate a fairly good kick, especially in the aluminum-framed guns that have become so popular among buyers, for their reduced weight and price.5 The recoil and blast penalty increases sharply when we step up to the +P loads that have gained favor for self-defense use, since their introduction in the early-1970s, as a means of squeezing better terminal performance out of the .38 Special.6

The .38 Special kicks in a small, lightweight gun, and there’s little you can do to avoid it. Some shooters will put oversized, cushioned grips on their gun to manage the recoil better, but these can make the gun unsuitable for concealed carry. Others will choose to load their gun with low-powered ammunition, like target-grade wadcutters, to reduce the recoil impulse, but that comes with complications of its own.7

Fixing the .38’s recoil is a problem that the .32 H&R Magnum can address, though. Most shooters will find the .32 H&R Magnum shoots soft, even with JHP ammunition intended for self-defense chores. The most recoil-shy shooters can even take it down a few more notches by loading .32 S&W Long or .32 S&W ammunition in the gun, which shoot even softer (akin to a .22 rimfire).8

The softer-shooting .32s offer the advantage of increased capacity, too. The J-Frame’s cylinder is only big enough for five rounds of .38 Special, but can hold six rounds of .32 H&R Magnum. One round may not sound like much in an era where we’re accustomed to autoloaders that hold upwards of 20 rounds, but it represents a 20% increase in capacity in these small guns, and there’s just something about having six rounds that feels “whole,” while having five often feels like a compromise. The psychological advantage of that sixth round is often more significant than the increased capacity, itself. 9

One last advantage of the .32 H&R is that it’s a centerfire cartridge. The traditional path for shooters seeking less recoil and greater capacity in a small frame revolver is to move towards a .22 Long Rifle or .22 Magnum. These cartridges do offer less recoil and greater capacity in comparison to the .38 Special, but their rimfire priming makes them less reliable.10 Rimfires, by nature of their design and construction, are simply more susceptible to ignition failures than centerfire cartridges, which is definitely a negative in a self defense gun.

Additionally, these rimfire cartridges demand a high energy hammer strike to ignite, which usually drives heavier mainspring weights in these small frame guns.11 In turn, the heavier mainspring generates increased trigger pull weights, which often exceed the trigger pulls on equivalent centerfire revolvers by several pounds. This creates a dilemma for the shooter who is seeking a gun that recoils less because they don’t have the hand strength (due to size, injuries or age) to handle more recoil—the rimfires recoil less, but their triggers are generally heavier than those on the centerfire guns, and more difficult for a person with compromised hand strength to operate.

The .32 H&R Magnum neatly sidesteps this problem because it’s a centerfire cartridge, with a less sensitive primer that doesn’t need a powerful mainspring to ensure ignition reliability. The cartridge kicks less, and allows for a lighter trigger pull weight, so it’s an excellent choice for the shooter with reduced hand strength.12

The .32 afficionados understood that all along, and as one of them, Jason was eager to see the UCs get chambered for the H&R Mag.13 He knew the question of “Why the .32 H&R?” would answer itself, as soon as people got a chance to shoot the guns.

FRONT SIGHT

Readers will recall from Part I that the UC project was primarily driven by a desire for improved sights on a factory J-Frame. Jason wanted an improved trigger and grips to go along with them, but the prime directive was to improve the sights on the J, to allow the shooter to hit quickly, with greater accuracy. The “Improved Sight 642” was given an experimental title of “642-S” to denote this emphasis on sights, as a result.

In their final production form, the UCs feature a pinned, XS Sights Standard Dot up front, with a bright green, photoluminescent ring (which XS calls the “Glow Dot”) to capture the shooter’s attention in normal to reduced lighting, and a Tritium lamp to do the same in low light. The large, bright green dot is easy to find and focus on, and the color offers a high level of contrast that will prevent it from blending into the target and its surroundings.14

Standard J-Frame sights have grown thicker over the course of 70-plus years of production, having started around 1/10th-inch wide (0.100”), but the current 1/8th-inch wide (0.125”) sight blade is still a little thin for some eyes, and can be difficult to acquire in a hurry, particularly through the restricted notch that’s milled into the top strap of fixed-sight Js.

The 0.140” wide post of the XS Sights Standard Dot is more useful for the short range, rapidly-evolving shooting scenarios that a J-Frame is most likely to be used in, but is also quite suitable for precision fire at longer ranges. It’s still possible to get a good sight picture without obscuring too much of the target at long distance with these larger front sights, because they’re properly regulated.15

That latter point is important, and requires emphasis. A high-visibility sight is only useful if it’s properly regulated, and throws bullets to the desired point of aim. The market has several compact revolvers that feature high visibility front sights that are NOT properly regulated, and it was a foundational requirement, from the very start, that the UCs would be different.16 The UCs would hit where they were aimed, when shot with the desired ammunition.17

An interesting aspect of the UC front sight, from a manufacturing standpoint, is the same XS Sights part is used on both the .38 and .32 caliber versions of the UC. The .32 and .38 caliber guns need different overall heights for proper regulation, but this is accomplished by changing the height of the front sight base, on each of the barrel shrouds, instead of creating two different sights. Sourcing a single SKU from XS Sights simplifies things from a logistical perspective, and also eliminates the possibility that a mistake could be made during assembly, when a worker installs the wrong front sight on a gun. It’s an elegant solution that illustrates the attention the Smith & Wesson engineering team was paying to the details of the UC project.

REAR SIGHT

The rear sight design is of Smith & Wesson’s creation, and features a U-shaped notch that mates well with the big, round dot on the front sight. The sight is serrated to reduce glare, and is plain black, without any distracting dots or other markings that could draw your visual focus away from the front sight, where it belongs.

The rear sight is dovetailed into the UC frame, and secured with a set screw to prevent it from drifting under recoil. It’s designed with a snag-free profile, which is necessary for a gun that will be carried in pockets, on ankles, underneath cover garments, and in off-body bags and purses.

The notch in the rear sight is both deep and wide, offering a generous window to quickly acquire the front sight, without being so sloppy that accuracy is affected. The notch is cut at 0.160”, to offer enough light on either side of the 0.140” front UC post that older eyes won’t struggle to find the front sight through it, as they do on standard J-Frames with their tight rear notches (which generally come close to matching the front sight width, at 0.125”).18

TWO-PIECE BARREL

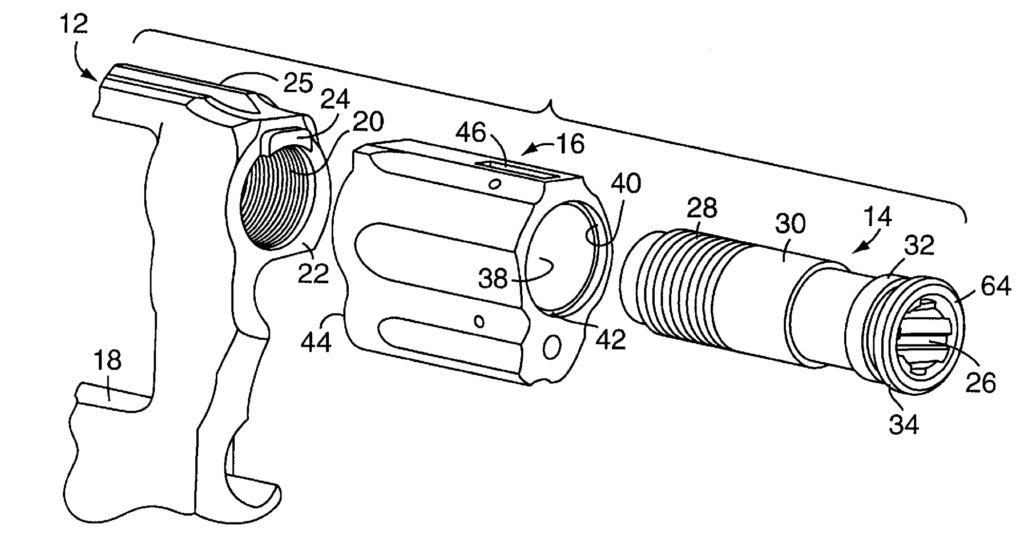

We’ve already mentioned the XS Sights Standard Dot sight that’s pinned to the sight base on the barrel shroud of the UC. Having a two-piece barrel system, like the one found on other Smith & Wesson revolvers of recent design (including the Scandium alloy frame Js), makes it easier to mount a replaceable sight like the one Jason wanted to use on the UCs, but there are other important reasons why a two-piece barrel system was specified for the project.

As we’ve previously discussed, “clocking errors” occur when a one-piece barrel with an integrated front sight post isn’t screwed into the frame properly, leaving the front sight canted to one side or the other. A barrel that isn’t turned into the frame far enough (most common) will leave the front sight canted to the shooter’s right, as he looks through the sights, while a barrel that is turned too far into the frame (less common) will leave the front sight canted to the shooter’s left, creating windage problems for the shooter.

Besides the windage problem, a clocking error can lead to frame damage when the barrel is turned too far into the frame (either during manufacture, or when trying to tighten the barrel later, to move the sight to top dead center). Stress risers in the frame can develop, and eventually lead to a crack in the frame that will make the gun unsafe to shoot. A cracked frame can’t be repaired, and the only way to remedy the problem is to replace the frame, or just scrap the gun entirely and replace it with a new one.

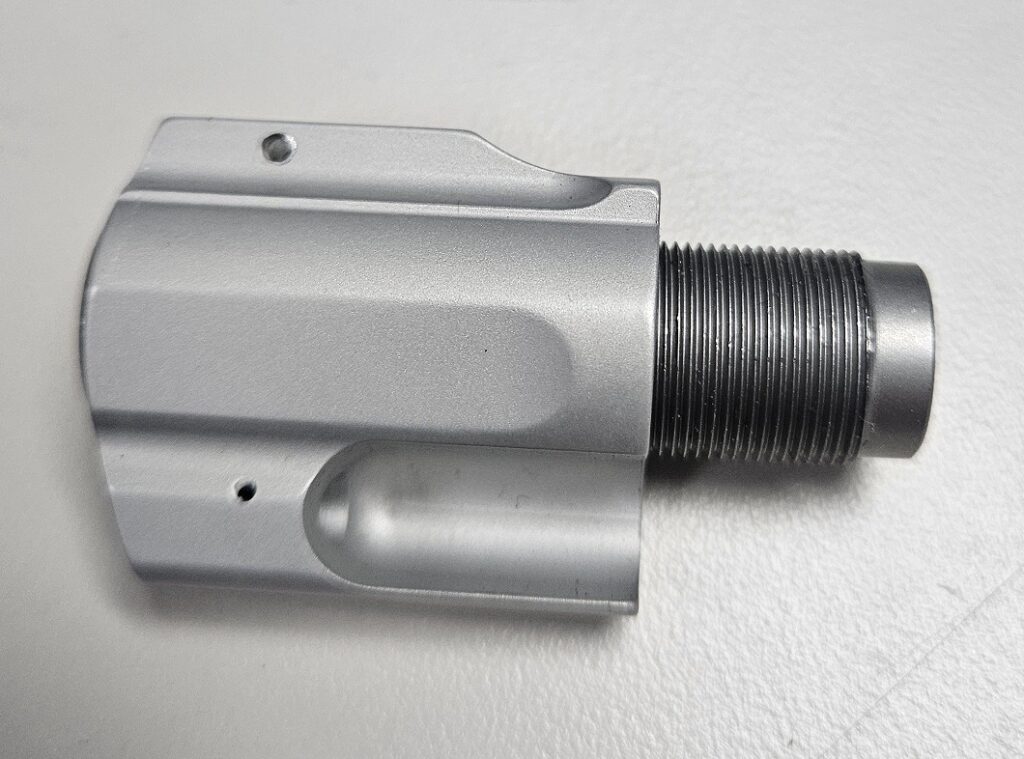

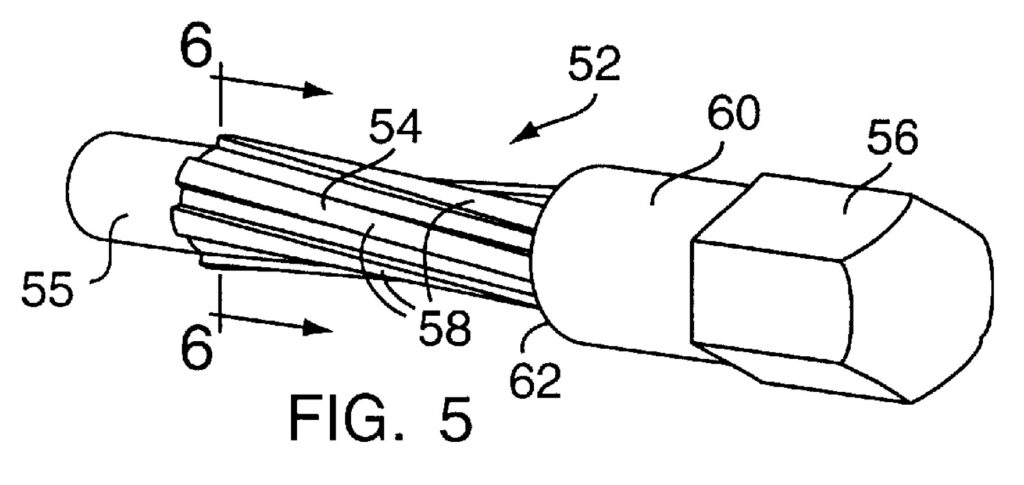

Battling these issues for decades led Smith & Wesson to adopt a two-piece barrel design, which simplifies barrel installation and eliminates the clocking issue entirely. In the two-piece design, a barrel shroud with an integrated sight base and extractor rod shroud is installed onto the frame, and properly aligned by use of a key or tab on the frame that mates with a matching recess in the shroud. The inner barrel sleeve, which looks like a threaded, stainless-steel tube with a belled mouth, is then screwed into the frame through the front of the barrel shroud. The belled mouth of the inner barrel sleeve bears upon the front of the shroud, locking everything in place as a single unit.19

The two-piece system boasts several advantages beyond maximizing front sight options, making it easy to time the sights properly, and avoiding frame cracks. First, it’s easy to set the proper barrel-cylinder gap tolerance with this system, and ensure this critical dimension is consistently maintained during production.20 Second, there is sufficient evidence to indicate the tensioned, two-piece barrel shoots with a higher degree of consistency and accuracy because the system does a better job of dampening barrel harmonics (and possibly resisting heat-induced barrel shifts), than the one-piece barrel system does.21

An additional advantage of the two-piece barrel system is that the shroud can be made from lightweight and inexpensive materials like aluminum, because it’s not a pressure vessel, just a cover for the pressure vessel (the barrel sleeve). Additionally, it’s easy to build shrouds with different profiles or features (different shapes or lengths, equipment rails, extractor rod tunnel lengths, sights and sight bases, etc.) and hang them on the same frame to create new models. Furthermore, it’s also easier to color match the frame and barrel (a cosmetic issue that has occasionally given S&W difficulties, when trying to match the finishes on aluminum 642 frames with their stainless-steel barrels and cylinders, for example).

FRAME REDESIGN

All of these advantages led Smith & Wesson to adopt two-piece barrel systems as part of their product improvement efforts, starting in the late 1990s. The Scandium alloy J-Frames in the catalog had been designed with them from the start, but the aluminum J-Frames had not kept pace, and were still being manufactured with one-piece barrels. Accordingly, the UC project provided Smith & Wesson with an ideal opportunity to update the aluminum J-Frames to the latest standard, with the new barrel.

The two-piece barrel system would require a new frame design with a tab for the barrel shroud, and a profile that would match the shroud’s contours where it met the frame. Since this major redesign was required, it was also a convenient time to fix a legacy problem with the aluminum frame—the frame studs/pins that supported the hammer, trigger, rebound slide, and cylinder stop.

These studs had always been one of the J-Frame’s vulnerabilities, from the very start. Over the course of time, the studs on the carbon and stainless-steel J-Frames had been improved with a new design that deleted the staking collar near the base of the old design’s stud, which eliminated a stress riser that could lead to the stud cracking at that location (the new steel studs are copper-brazed in place now, instead of being staked). Similarly, the Scandium alloy guns had been improved with the installation of robust Titanium studs that were press-fit completely through the wall of the frame, staked, and made flush on the outside (I’d guess as part of the final machining of the frame’s exterior).

It’s now quite rare for the studs on a steel or Scandium alloy J-Frame to break, but the aluminum guns had received no such upgrades over time, and still featured aluminum studs that were pressed into shallower, blind frame holes, and staked in place. While these studs were strong enough to last several typical J-Frame lifetimes, and were rarely a problem for the vast majority of owners, the most dedicated and enthusiastic J-Frame shooters could sometimes break a stud with high-volume training, and Smith & Wesson’s engineering team wanted to address this lingering problem with the UC frame redesign.22

The UC’s frame was therefore changed to include Titanium studs like those found on the Scandium alloy guns. The robust studs are press fit completely through the frame and staked, as they are on the Scandium guns. You can see the heads of them on the port side of the UC’s aluminum frame. These Titanium pins constitute the UC’s “Endurance Package,” and guarantee an improved service life for these guns, compared to those made on the legacy aluminum frames.

Another feature that will extend the life of the new aluminum frame on the UCs is the addition of a steel center pin bushing, in the bolster (breech) face of the frame. This bushing will limit erosion where the center pin locks into the frame, and rubs against the port side of the hole as the cylinder is pushed out of the frame. The legacy aluminum frames were not reinforced here, and the steel center pin could eventually make the hole in the aluminum frame a little oblong, as it wore.

ACTION

When a shooter cycles the UC’s action for the first time, they’ll notice it’s better than the factory action on the legacy aluminum Js they’ve grown accustomed to.

The reduced pull weight is the result of new spring rates for the mainspring and rebound slide spring on the UCs, which were optimized by S&W’s engineers. Importantly, the reduced pull weight does not sacrifice ignition reliability, nor does it leave the gun with a sluggish trigger return, which could encourage short-stroking the trigger when the gun is being fired rapidly, under stress.23

The UC’s action also benefitted from the attention paid to the frame redesign. To explain, any item that’s produced for a long period of time develops some level of tolerance stacking, as a natural byproduct of the manufacturing process. As new machines, software, and tooling replace old ones, and certain parts get tweaked while others remain unchanged, there’s a natural creep in manufacturing tolerances that can occur.24

As the legacy aluminum frames hadn’t received a serious update in more than two decades (since the CNC machining and MIM manufacturing revolution of the late 1990s and early 2000s), there was likely some degree of tolerance stacking that had accumulated in the design. The effort to update the aluminum J-Frame for the UC project therefore gave Smith & Wesson an opportunity to start fresh, and make sure all the tolerances were exact and optimized in the new frames. The shooter will feel the result of this house cleaning in the trigger pull.

The net effect of Engineering’s work on the UC’s action is to create a trigger pull that’s smoother and lighter than what we’ve become accustomed to on the legacy, aluminum J-Frames. It’s not a custom action, but it’s a very good factory production action, and most shooters will be able to appreciate the improvement right away. It will get even better with a few hundred trigger presses, based on my experience with a couple samples.

CONTROLS

The UCs retain familiar controls, which is generally a good thing. While I would have liked to see a more aggressively melted thumb piece, to avoid “J-Frame thumb,” this is a detail that can be easily attended to by the owner. I’ve had to polish the bottom and rear edges on S&W thumb pieces for decades, so they wouldn’t bite my thumb knuckle as much, and if that’s the concession I have to make, to gain all the other wonderful benefits of the UCs, it’s a trade I’ll be happy to make.

The UC’s 0.312″ smooth combat trigger is noteworthy for its width, contour, and lack of square corners. I’ve had some difficulties with the triggers on the new Colt Cobras and the Ruger LCR38, which can be uncomfortable to shoot at times, and was happy to see Smith & Wesson retained the features which have always made the J-Frames feel therapeutic to my trigger finger, by comparison.

Perhaps the most notable control on the UCs is the one that isn’t there—the dreaded key lock, which began to deface Smith & Wesson revolvers in 2001. While the Centennial-style revolvers have been more immune to the lock failures that have rendered some lock-equipped, external-hammer guns inoperable, many of us still find them objectionable for their symbolic and cosmetic properties, and it’s wonderful (and encouraging) to see they were not included on the UC J-Frames. 25

No “Ultimate” gun could include the darned lock!

CYLINDER

Even if they didn’t dress up the thumb piece, Smith & Wesson did see fit to bevel the leading edges of the UC’s cylinder, in “black powder” fashion.26 This is a nice touch, which will ease holstering and prevent tightly-fitted holsters from getting scarred up by sharp leading edges and corners. It’s also kinder on the hands as you’re manipulating the gun during loading and unloading, and it looks attractive, to boot.

On the back end of the cylinder, each of the UC’s chambers is lightly chamfered as well, which will aid in loading the revolver, especially with the blunt wadcutters that were expected to be routinely fired in these guns.

GRIPS

We discussed the evolution of the UC grips at length in Part I of the series, and won’t recreate it here. There are a several important features of the grips that bear mention, however.

The first is that they are fully compatible with the market’s most popular round-body speedloader designs, and won’t interfere with their operation. There are many grips on the market that offer a token speedloader relief, but the VZ Grips on the UC offer true compatibility with high-profile loaders like the HKS and Safariland Comp I, and the loaders won’t bind as you try to use them.

The second is that the grips were designed with features to help mitigate the effects of recoil, and improve the shooter’s control of the gun. A covered backstrap, and high horns that reach up to the frame’s recoil shoulder are designed to fill the hand better and distribute the gun’s recoil across a larger surface area, thereby making it more comfortable to shoot.

The third is the grips were designed with a smooth texture for comfort, concealment, and performance. The smooth surface won’t abrade your hand, even when powerful loads are fired in this lightweight gun. It will also allow the gun to ride comfortably in pockets, or in holsters carried up against your skin. Lastly, it will resist grabbing your cover garments, thereby reducing printing, and will allow you to make adjustments to your firing grasp, without any difficulty, if you don’t land on the perfect spot during step one of your presentation.

A final takeaway is that the grips were designed to be compact and concealable. These are not grips intended for target shooting or for situations where concealment is not a priority. In those environments, you can afford to mount an oversized grip to your gun to enhance your comfort and control, because you don’t have to worry about hiding it. The “C” in “UC” stands for carry, however, and the principal design objective was to make a grip that offered the best comfort and control possible, without sacrificing the compact and concealable profile that the J-Frame snub is chosen for. The “boot”-style grips on the UC are compatible with tight spaces like pockets, ankle holsters, and purses, and will disappear if the gun is carried in suitable holsters, using good technique.

The grip is where the shooter and the gun meet, and since there’s an endless variety of hand shapes and sizes, there’s also an endless variety of opinions on what makes a “good” or comfortable grip. I personally think the UC grip is excellently suited for its mission, but the good news is that the grips are easily replaced if the shooter desires a different feel to make their gun feel like the ultimate carry revolver.

LOOKING AHEAD

That’s gonna do it for this installment, but we’ll be back in Part III to discuss my experience shooting the UC J-Frames at the Lipsey’s media event. By that time, you’ll be tired of hearing me talk, but still eager to hear more about the UCs, so we’ll get Kevin up to bat next, to give you his comprehensive evaluation of the 432 UC, which is currently underway.

In the meantime, keep your eyes peeled for one of the UCs at a Lipsey’s dealer near you. They’re getting shipped every week, and yours will be there soon. That includes you RevolverGuys behind the Golden Curtain, in California—the guns have already been submitted for review and testing by a state-approved laboratory, and Smith & Wesson hopes to have them certified, and on the DOJ Roster soon. Start saving your pennies, and building up your ammo stash now!

*****

ENDNOTES

1.) Smith & Wesson’s first revolver, the Model 1, may have been a .22 rimfire, but their second revolver, the similar Model One-And-A-Half (1-1/2), was a .32 rimfire. These pre-Civil War, rimfire “tip-up” designs were superseded by a series of centerfire “top-break” revolvers after the war, such as the (similarly numbered) Model One-And-A-Half, chambered in .32 S&W. Various models of .32 caliber top-breaks were built from 1878 (Model 1-1/2) to 1937 (Safety Hammerless 3rd Model—the “Lemon Squeezer”).

The solid frame, swing-out cylinder, double action, Hand Ejector models, that we would recognize as the grandparents of today’s Smith & Wesson double action revolvers, were launched in 1896, with the First Model .32 Hand Ejector in .32 S&W Long (a lengthened version of the earlier .32 S&W). These small, I-Frame guns evolved through several model designations until 1961, when the J-Frame was introduced. The J-Frame completely replaced the I-Frame in the catalog, and Smith & Wesson spent the next four decades manufacturing .32 caliber snubs on this small frame. Various J-Frame models were offered in .32 S&W Long and .32 H&R Magnum, with traditional, external-hammer frames (made from carbon steel or aluminum alloy), or Centennial-style frames (made from aluminum alloy, stainless steel, or Scandium alloy).

By 2006, the last of the .32 H&R Magnum snubs (the Model 431 PD Chiefs Special Airweight, and Model 432 PD Magnum Centennial Airweight) were gone from the catalog. Shortly after Federal launched the lengthened .327 Federal Magnum in 2007, the 632 Pro Series and 632 Carry Comp Pro revolvers, chambered in the new cartridge, made a short appearance in the Smith & Wesson lineup. However, they didn’t last long, and were gone almost as soon as they arrived.

Interestingly, Smith & Wesson continued to make some .32 caliber Model 431 PD revolvers for foreign police contracts in Asia, but none were being made for the domestic market. For American consumers, the era of the .32 revolver had passed at Smith & Wesson.

2.) By the time Lipsey’s Jason Cloessner pitched the “Ultimate Carry” guns to Smith & Wesson in the summer of 2022, the .32 H&R caliber J-Frames had been missing from the American market for over 16 years, and had started to achieve a semi-collectible status. Shooters who wanted to carry a .32 J were having to search near and far, and pay some pretty steep prices, to get one, since it didn’t look like we’d ever see another one from the factory.

Ruger was the brand that really carried the torch for small frame .32s during this period, keeping their popular LCR 327 and SP101 revolvers chambered in .327 Federal Magnum in continuous production. Charter Arms introduced their Professional in .32 H&R in 2021, but production numbers were low and I never saw any in the wild. Taurus made some .32 H&Rs off and on, and announced a special run of .327 Federal Magnum revolvers for (now defunct) distributor Ellett Brothers at the 2008 SHOT Show, but those guns disappeared quickly, and while I’m not sure, I don’t think Taurus added a small frame .327 Federal Magnum to the catalog as a regular item until the 2022 SHOT Show. The gun world was not awash in brand new .32 caliber snub choices, and the pantry was bare at Smith & Wesson.

3.) A critical part of the UC’s success was the team that Jason assembled from across the industry to support the product. We’ve previously talked about the involvement of vendors like XS Sights and VZ Grips in Part I, but a critical part of Jason’s outreach included ammunition vendors like Vista Outdoor (Federal, Speer, Remington), Doubletap Ammunition, and Lost River Ammunition. If the .32 H&R Mag UCs were going to be a success, they would need a ready supply of food, so Jason beat the bushes and encouraged these vendors to produce more .32 caliber ammunition in advance of the UC’s launch.

In response, Remington announced the addition of .32 H&R Magnum High Terminal Performance and Performance Wheelgun loads to the 2024 catalog, and Federal committed to producing more of their existing .32 H&R Magnum SKUs in 2024, while they developed more advanced JHP designs, using knowledge gleaned from their .30 Super Carry project.

Doubletap’s Mike McNett launched several new products to support the UC, and Lost River’s Ted McIntyre created a new .32 H&R Mag wadcutter. I got to shoot these rounds in February 2024 at the Lipsey’s media day, and will discuss them in greater detail in Part III of this series.

There’s a renewed energy surrounding the .32, and while the ammo supply isn’t robust right now, it’s only going to get better as manufacturers respond to the increased demand from the market. Things are going in the right direction for the .32, which, in my opinion, is in the early stages of a 10mm-like comeback.

4.) The associated question–“why didn’t they chamber it in .327 Federal Magnum?”–usually comes next.

This one is easy to answer, as the aluminum frame of the UCs is simply not strong enough for this high-pressure round. At a Sporting Arms & Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) Maximum Average Pressure (MAP) of 45,000 psi, the .327 Federal Magnum operates at nearly double the limit of the .32 H&R Magnum (23,000 psi MAP) chosen for the UC project.

Indeed, the 45,000 psi MAP .327 Federal Magnum is one of the hottest handgun rounds approved by SAAMI. By comparison, the .38 Special is rated at 17,000 psi, the .38 Special +P is rated at 20,000 psi, the .357 Magnum is rated at 35,000 psi, and the mighty .41 and .44 Magnums are only rated at 36,000 psi. In revolver cartridges, one has to look at big bore powerhouses like the .480 Ruger (48,000 psi), .475 Linebaugh (50,000 psi), .500 S&W Magnum (60,000 psi), or .454 Casull (65,000 psi) to exceed the little Federal Magnum’s MAP.

A different frame material, like steel or Scandium alloy, could have been used to support a .327 Federal Magnum chambering, but it was important to stick with the aluminum frame for two reasons—weight and cost. A steel frame would be heavier than most J-Frame owners prefer, and more expensive to produce (both reasons why the aluminum J-Frames have traditionally outsold the steel J-Frames by a large margin).

In contrast, a Scandium alloy frame would keep things light, but the price would skyrocket into the four-figure range, and nobody would shoot the .327 Fed Mag in a gun that light anyhow—at least not more than once. Having fired full-power .327 Fed Mag loads in a 17-ounce Ruger LCR, I’m completely disinterested in shooting the cartridge in a 12-ounce Scandium alloy J-Frame! For that matter, I’m not interested in repeating the LCR experience, either, and figure I’m in good company, because everyone I know with one of these guns loads it with .32 H&R Magnum or .32 Long ammo when they want to shoot it. Most shooters seem to reserve the .327 Fed Mag loads for heavier guns like the SP101, at 27 ounces.

So, the .32 H&R Magnum is definitely the sweet spot for a .32 caliber UC. It allows the use of the light and affordable aluminum frame, while keeping recoil manageable for the average shooter. It keeps the UC within reach of the “everyman” or “everywoman” customer on both cost and performance fronts.

5.) There’s no shortage of personalities in the shooting world who would balk at my characterization of the .38 Special’s recoil, but I’ll stick by it, even if they think I need to eat more spinach.

The .38 Special doesn’t generate a lot of recoil energy in service size, steel frame guns, but when you start talking snubs—even the heavier ones, with steel frames, but especially the lightweights, with their aluminum alloy or polymer frames—the picture changes. The .38 Special is not punishing to shoot in a small frame snub revolver (I’d reserve that description for the .357 Magnum, which is generally pretty awful, and often downright painful, to shoot in alloy snubs with any cartridge that’s not downloaded, and is worthy of the Magnum moniker), but it does generate a potent kick, especially if the gun is wearing a reasonable grip for concealed carry.

Standard pressure 130 and 158 grain loads will wear out most snub shooters by the time they’ve finished 50-100 rounds, and the more recoil-shy won’t even make it past a few cylinders before they’ve had enough. Even the most experienced and committed shooters will get fatigued, sore, and weary of the recoil by the time they’ve finished a full day of training with .38s in a small frame revolver with concealment grips. These are not the guns you would want to take to a five-day class, like a Gunsite 250, unless you’re one of those guys that lives way out on the far end of the bell curve. There’s a reason why they developed a reputation as “phone booth guns” that were difficult to control and shoot accurately beyond arms’ length, and the recoil was an important part of the equation (along with the grips, sights and triggers—areas where the UC shines, due to the attention the Lipsey’s-Smith & Wesson team has paid to them).

I’ll talk more about my experience of shooting the UCs in Part III of this series, but I managed to shoot approximately 480 rounds of .38 Special in the course of a day while testing the guns, and I was pretty sore and fatigued when it was done. I certainly wasn’t ready to do it again the next day. The guys who tell you the .38 “doesn’t kick” in a snub, are usually the ones who do a better job of talking the talk, than walking the walk, in my experience.

6.) We’ve previously discussed how the .38 Special doesn’t have a large surplus of energy to do work when it’s fired from the shortened barrel of a snub revolver. As such, many shooters have chosen to accept the increased recoil and muzzle blast that comes with the .38 Special +P and +P+ loads that generate enough velocity and energy to ensure a reasonable degree of bullet expansion and penetration. Even then, the .38 Special can come up short on one or the other—you often have to choose if you want expansion or penetration from a .38 snub, because you often can’t get both. There’s a few loads out there, like the Federal Hydra-Shok Deep and Speer Gold Dot that do a pretty good job of threading the needle, but It’s the nature of .38 snub loads that you can’t always get what you want, as Mick told us.

7.) It’s become increasingly popular to suggest using wadcutters for self defense in the last several years, and many of the revolver world’s most influential trainers and writers have become strong advocates of the practice. They have made the conscious decision to sacrifice bullet expansion for penetration, and energy for enhanced control, by loading their revolver with low-powered, target-grade wadcutters (or specialty wadcutters, like the Georgia Arms Ultimate Defense load) that don’t expand, but run deep.

That’s not a bad solution to the problem of managing snub recoil, but it does come with some downsides. The wadcutter profile makes it harder to load into chambers, especially with round-body speedloaders, which turns an already-slow operation into an even slower operation. Additionally, soft lead wadcutters tend to be really dirty, and can foul a revolver much more quickly than jacketed bullets, so you have to clean more often and more thoroughly if you’re going to shoot wadcutters. Lastly, it’s been difficult to find wadcutters for sale during the last several ammo panics, as manufacturers tend to focus their efforts on making FMJs and RNLs when they have limited production time for .38 Special. When you can actually find them, they’re usually priced at a significant premium, often costing more per round than some JHPs.

So, the 148 grain wadcutter isn’t a bad idea, but it’s not a perfect solution, either. Additionally, we should probably note that loading target wadcutters into a .38 Special snub brings the recoil closer to the .32 range, so if achieving .32-like recoil is the objective, then why not benefit from the additional capacity offered by the .32’s six-shot cylinder? Hmmm.

8.) In the same way that a .38 Special can be safely fired in a gun chambered for the longer .357 Magnum, the .32 S&W Long, and the even shorter .32 S&W (often called the .32 S&W Short), can be safely fired in a gun chambered for .32 H&R Magnum. The three cartridges share identical dimensions (nearly identical, in the case of the .32 S&W), outside of case length, so any of the shorter cartridges can be fired in a .32 H&R Magnum gun. The longer .327 Federal Magnum cannot be fired in a .32 H&R Magnum gun, but the shorter .32 S&W, .32 S&W Long, and .32 H&R Magnum cartridges can be safely fired in a .327 Federal Magnum revolver.

9.) See my article on the Compact Service Revolver for more thoughts on this phenomenon.

10.) A rimfire case is primed by inserting a drop of priming mix into the bottom of the case, then spinning the case to distribute the mix throughout the rim by centrifugal force. While the method normally distributes the mix fairly evenly, there are times when sections of the rim are left with no priming mix, or insufficient priming mix. If this happens to be the part of the rim that gets crushed by the firing pin during shooting, then the cartridge will fail to ignite. Such difficulties are not usually encountered with the Boxer or Berdan primers used in centerfire cartridges, making them more reliable than rimfires, in general.

11.) In a gun with a larger frame, there is more space to use a larger hammer with greater mass, or to change the geometry of the action to obtain greater mechanical advantage. The compact dimensions of a small frame revolver limit these other remedies though, which leaves increasing the mainspring weight as the only viable solution for ensuring there’s enough energy to deform a rimfire’s case, and crush the priming mix that’s sandwiched inside, to create the spark that will light off the powder charge.

12.) These were some of the factors that encouraged me to recommend a S&W 632 for a friend’s wife in the late 1990s. She wasn’t “into guns,” and was a little recoil-shy, but she wanted to carry a firearm for personal defense to protect her two young children.

As a busy mom, and the wife of a military pilot who was frequently absent for extended periods, it was unlikely she would have the time or inclination to do lots of handgun training, so a simple manual of arms was desired. While she was healthy and athletic, she was also very petite, so felt recoil was an important factor. She had shot a variety of .380 ACP and 9mm pistols and didn’t like shooting any of them, because they “kicked too much.”

These factors, combined with the reality that the gun was normally going to be carried off-body, in a purse or bag, but sometimes in a coat pocket, pointed towards a compact revolver with no hammer spur to catch on clothing or bag openings. A rimfire was a possible candidate, but the trigger pulls were heavy and all the models in production at the time featured external hammers, so they were dismissed before we even had to arm wrestle about the viability of the .22 as a defensive round.

While the .32 H&R Magnum’s popularity was already starting to sunset by this time, there was still a reasonable amount of ammunition in the supply chain, and a slightly-used Model 632 wasn’t too hard to locate. The heavy steel frame of the 632 would easily soak up whatever recoil the .32 H&R Magnum had to offer, the hammerless Centennial frame would be ideal for the intended carry methods, and the trigger was easier to work than the ones on the rimfires.

It seemed like a natural choice, and it turned out to be a great success. The gun met all her needs and she enjoyed shooting and carrying it. The .32 H&R Magnum Federal JHPs that her husband wisely bought in bulk (and which kept them afloat during several ammo panics, and the long dry spell ever since) were potent, yet didn’t abuse her hand.

When I visited the family in February of 2024, after a long period of not seeing them, the wife made a reference to “my gun” in conversation, and I asked her what she was carrying these days, half-expecting her to describe some flavor of subcompact 9mm pistol, like the ones her husband favored. I was very pleased to hear that she was still carrying the Model 632, over two decades later. She still enjoyed shooting it, and she still felt well protected by it. The .32 H&R Magnum revolver made sense in the 90s, and it still makes sense now—for her, and a for lot of other people.

13.) Another one of those .32 afficionados was trainer, writer, and industry professional Darryl Bolke, who lobbied Jason for a .32 UC from the moment that Jason approached him about the project, in March of 2023. Jason didn’t need any convincing, but was encouraged to have the support of someone like Darryl, who was an influential person in the industry, with a history of being a strong .32 advocate. Having Darryl’s endorsement made it easier for Jason to sell the uninitiated and skeptical folks out there on the .32 as a defensive choice.

14.) As we reported in Part I, when American Fighting Revolver’s Darryl Bolke and Bryan Eastridge joined Jason Cloessner and Smith & Wesson’s Andrew Gore on the range to shoot the prototype 642 UC in October 2023, the team discovered the yellowish-color of the prototype’s sights didn’t offer enough contrast, and decided to ask for a darker color.

I personally have an affinity for bright, orange-red colored front sights, and suggested an Ameriglo CAP-style sight (or alternatively, a Trijicon HD-style sight) in that color when Jason and I discussed the UC concept in March of 2023. I’ve found a big, square, orange-red post is a nice combination for sights that need to be found quickly, and it sounds like Darryl had similar color advice in his parallel conversations with Jason during the same timeframe.

However, Darryl had an interesting idea (discussed here, at 13:15, for American Fighting Revolver members with access to the video) about the UC sight color choice, which helped to drive the team towards the final green color. As Darryl explains, the UC (particularly the .32 caliber model) was expected to be very attractive to inexperienced shooters without a lot of formal training (what we call “non-dedicated personnel,” or NDPs, in the military), and there was a value in choosing a sight color that kept things consistent, regardless of lighting conditions. The Tritium vial would glow green in low light, just as the photoluminescent ring would glow green in regular light, and this kind of consistency and simplicity could benefit the less highly trained and experienced. A flash of green, superimposed on a verified lethal threat, would be the visual cue necessary to press the trigger regardless of lighting conditions (“Green means GO,” as Darryl explained it at the Lipsey’s media event in February 2024) with this system.

It makes sense. Simple is good, and so is consistency when we’re working under stress. My experience with the green front sight was very positive at the media event, and I think the team made an excellent choice with the XS Sights Standard Dot in that color. It’s a superior sighting system for the UCs.

15.) I’ll discuss my shooting experience with the UCs in greater detail in Part III, but for now will simply point out that I was successfully engaging 10” steel plates with about 70% -80% of my shots at 50 yards, using a .38 caliber 642 UC, at the Lipsey’s media event, and found the XS Sights to be perfectly suited for the task.

16.) We’ve discussed sight regulation in great detail in these pages, and have documented our frustrations with various guns and their sights. Justin detailed the issues he encountered with his S&W 640 Pro, and I wrote extensively about my issues with the Kimber K6s revolvers, and my frustration with Kimber’s inexplicable choice of a Buffalo Bore, 158 grain .357 Magnum baseline, and their engineering team’s continued reluctance to provide a replacement sight option that would work better with the loads real people shoot in the guns (fortunately, Kimber did a MUCH better job on the new K6xs revolvers, which are properly regulated for appropriate .38 Special loads—thank you, Kimber!).

Experiences like these drove the UC requirements from the start. Jason was already leaning towards the Speer 135 grain Gold Dot as the baseline load for the .38s when I suggested the same in March of 2023 (as did Darryl, and several others), and we were also on the same page of using 15 yards as the zero distance. I asked Jason to, “make the sights easy to see like the Kimber’s, but make them hit to point of aim,” and that’s exactly what Smith & Wesson did, at his request.

17.) The .38 caliber UCs are regulated to hit point of aim with 135 grain Speer Gold Dot and standard pressure 148 grain wadcutters (circa 600-700 fps) at 15 yards, and the .32 caliber UCs are regulated to hit point of aim with Federal Personal Defense 85 grain JHPs and 100 grain wadcutters in the circa-800 fps range.

The 135 grain Speer Gold Dot has been in short supply for several years, and I’ve already heard from RevolverGuys who are confused why an “unobtanium” load would be chosen as the baseline for sight regulation on the .38 UCs. The Gold Dot’s real-world reputation for excellent terminal ballistic performance was a primary consideration, but an additional advantage is this middle-of-the-road load, with velocities around 800-850 fps from a 2” gun, shoots to a point of aim that’s closely matched by other popular loads.

The .38 Special +P 130 grain Federal Hydra-Shok Deep and the .38 Special +P 130 grain Winchester Ranger Bonded / PDX1 Defender have strong terminal ballistics and hit to the same point of aim as the Gold Dot (both loads are a little faster than the Gold Dot, shooting around 850-875 fps from a 2” gun). The .38 Special +P 129 grain Federal Hydra-Shok approaches the Gold Dot’s velocity, at around 800 fps, and the popular 120-125 grain JHP loads, like Remington’s Golden Saber, Federal’s Punch, and Sig Sauer’s V-Crown, shoot a tad faster, around 875-925 fps, but will hit very close to the same point of aim.

So will the loads that are most commonly used for practice. Standard pressure .38 Special 130 grain FMJ shoots around 750-800 fps and will hit to the UC’s sights, as will 148 grain target wadcutters, at around 600-700 fps. The latter, as we’ve already discussed, is a good defensive option in the UC, as well.

If you favor the 90-110 grain lightweights, or the 158 grain heavyweights, you’ll notice a larger deviation from your point of aim when shooting them in the UC, but because the UC’s sights favor the middle ground, the difference won’t be as extreme as it is on the legacy J-Frames, when you try to shoot 110 grain loads in a gun with sights regulated for 158 grain loads.

So, don’t fret if you can’t find the Gold Dot on the shelves—there are plenty of options out there that will hit to the same, or nearly the same, point of aim, and deliver similar terminal performance. It was all part of the plan.

18.) The 0.160” wide rear sight notch was something I requested during my March 2023 conversation with Jason, and I’m grateful that he wrote it into the specifications for the UCs.

I’ve always felt the rear notch on the J-Frames was tight, and adopted the technique of shooting “out of the notch” when distances were close, and engagement speeds were fast, as a workaround. As I’ve aged, I’ve found it increasingly difficult to take a more deliberate aim through the tight rear notch on my Model 640, and was happy with the results when good friend (and serious RevolverGuy) Dean Caputo opened it up slightly with a few file strokes, to fix a clocking issue, during a visit to the armorer.

An early childhood experience with my Dad’s off-duty gun, a custom Browning Hi-Power, fitted with a Millet rear sight with a generous notch, showed the benefit of having more light around the front sight for rapid acquisition. More recent experience with the Kimber K6s revolvers, and some custom revolvers fitted with Dave Lauck’s outstanding sights, reaffirmed how having an enlarged rear sight window could dramatically improve a revolver sight picture, in the same manner that the tight and shallow windows on standard J-Frames and the new 2020 Colt Python demonstrated the opposite effect.

Dean and I had already been talking a lot about these sight dimension issues when Jason approached me about the UC in March 2023. As we talked, I reflected on Dean’s experience with opening the rear notch on his new, 2017 Colt Cobra (made with a front sight and rear groove that each measure approximately 0.135”, from the factory) to a generous 0.160”, which gave him extra light on either side of the front sight. It was working great for him, and I thought it would work equally well with the 0.140” front sight that Jason was planning to use for the UC.

Jason had originally planned to go with 0.150” notch in the rear, but I asked him to use a 0.160” notch instead, and he went with it. It worked exactly as planned. One of the first things a shooter will remark about when he picks up the UC for the first time is how good the sights are, and how easily he can see them—a scene that I’ve seen play out so often with first-time shooters of the Kimber K6s revolvers (myself included), that I’ve jokingly termed it the “K6s Experience.” Well, now it’s the “UC Experience,” with the added benefit that you don’t have to be shooting 158 grain .357 Magnum ammo to hit exactly where you’re aiming!

Jason kindly gives me credit for the 0.160” rear notch on the UCs (see his description, around 1:43:40), but the truth is half the credit belongs to Dean, so make sure to thank him and buy him a coffee if you ever run into him!

19.) Smith & Wesson Manufacturing Engineer Norm Spencer, a prior S&W model-maker who helped Senior Product Engineer Dick Baker craft the first L-Frame revolvers, and Smith & Wesson’s first .40-caliber autopistol, among many other professional accomplishments, led the team that developed and patented both the tool and the method for installing the two-piece barrel assembly into the frame, during the development of the first Titanium and Scandium guns.

At first, Smith & Wesson had considered screwing a thin barrel sleeve into the frame, then trimming it to length, and installing a shroud over the top of it. However, this was not a good solution from a manufacturing perspective, as it didn’t translate well to large scale production. Furthermore, the earlier Dan Wesson system of barrel installation, with a nut that secured the shroud to the frame, was not desired for cosmetic reasons, the potential for damaging the barrel shroud or frame while wrenching the components into place, and because S&W wanted a system that prevented an owner from easily removing the barrel.

Norm came up with the idea of a wrench with engagement surfaces that precisely matched the rifling in the barrel sleeve, which allowed the barrel sleeve to be screwed into the frame with the proper amount of torque, through the front of the shroud. The belled muzzle on the barrel sleeve would not only keep the shroud in place, it would camouflage the exterior threads on the sleeve itself, and fill the unsightly gaps that were a byproduct of the Dan Wesson nut system.

The patent for the two-piece barrel system (US Patent Number 6,266,908 B1, dated July 31, 2001) lists the members of Norm’s team as its inventors. In a fun twist of RevolverGuy history, one of those team members was a young engineer named Brett Curry, who readers may recall from Part I as one of three senior engineers who provided guidance to Lead Product Engineer Andrew Foley, as the younger Foley did the engineering work on the UC project in 2023.

20.) American Fighting Revolver’s Bryan Eastridge reports finding uniform barrel-cylinder gap tolerances during his inspection of the first batch of UC revolvers at the Lipsey’s media event in February 2024. More about this in Part III of this review, later.

21.) More on this, based on my experience shooting the UCs, in Part III, as well.

22.) Smith & Wesson Engineering had long wanted to upgrade these parts on the aluminum J-Frames, but there had never been a sufficient pause in production to allow them to do so. The improved studs had been an important part of the Scandium alloy frame design, along with the two-piece barrel system, which had made those guns more robust than their aluminum counterparts, so the engineering team was delighted when Andrew Gore gave them the direction on 24 March 2023 to, “treat this (UC project) as the new generation of aluminum J-Frames, and do all the improvements you have always wanted to do.” The engineers now had free reign, and weren’t going to hold anything back. The new UC aluminum frame would be treated to the entire menu of long-delayed product improvements, including an “Endurance Package” with better studs for the hammer, trigger, rebound slide, and cylinder stop.

23.) Unfortunately, these are byproducts of some aftermarket spring kits, which can negatively affect the gun’s reliability, in the quest for a lighter pull weight.

While many people measure whether or not a trigger is “good,” based on its pull weight, there are other factors which must be considered. A good revolver action is reliable, first, and smooth, second. It must positively reset the trigger after the sear trips, and not have excessive overtravel which could encourage pulling the bore off target. A lighter trigger pull is preferred if these other qualities can be maintained, but I wouldn’t sacrifice one of them in the quest for a lighter trigger.

24.) Anyone who closely followed the saga of the Marlin lever actions understands this phenomenon. As the decades passed, and machines and tooling wore out, the tolerances on these century-old guns were constantly changing, to the point that the engineering drawings were no longer an accurate picture of the gun when production was moved from North Haven, Connecticut, to Mayfield, Kentucky, following the 2007 acquisition of Marlin by Remington Outdoor Company. The Remington-produced guns developed an early reputation for problems, as a result of tolerance stacking issues that Remington never fully resolved before production ceased with the company’s 2018 bankruptcy. After purchasing all the Marlin designs and assets in a 2020 bankruptcy sale, Ruger had to completely “blueprint” the guns (determine the proper dimensions and tolerances, and update the engineering drawings to match) before they could program machinery and start making guns.

A less extreme example of the phenomenon is the continuous growth of the Colt Single Action Army’s hard rubber grips, which grew slightly bigger with each generation as the tooling/molds continued to wear with use.

The legacy aluminum J-Frames weren’t in bad shape, but there was probably some tolerance stacking going on under the hood, all the same. The new UCs have tightened things back up, and the action feels better, for it.

25.) As we’ve previously reported, the external hammer guns seem more prone to lock failures that render the gun inoperable, because they have visible “flag” indicators that pop up into view when the action is locked. These flags are lightly sprung, and can move under recoil and interfere with hammer operation, sometimes binding it in place. There have been reported lock failures in the hammerless, Centennial-style frames which lack the flags, but these occurrences seem to be much less common.

Actually, lock failures of any sort have seemed to diminish in the last ten years or so, because we just don’t hear much about them anymore. This leads me to assume that a successful engineering change or redesign quietly corrected the mechanical deficiency at some point.

That’s a good thing, but it only addresses part of our opposition to the lock. The lock is unsightly, and the guns would look much better without them, but the more significant issue is the symbolic nature of the lock, which is a legacy of the HUD-S&W agreement victory won by powerful, anti-gun forces that worked to deprive us of our liberty during the Clinton era. It’s an embarrassing and repulsive reminder of our defeat (actually, of the surrender made by Smith & Wesson’s former British owners, who are thankfully no longer running the company), that we would like to see removed from the guns.

It is VERY meaningful to us that the UCs are not equipped with a lock, and we hope Smith & Wesson management will understand how critical this was to the success of the project. No matter how good the UCs were, we would not have embraced them so completely, and so enthusiastically, if they had been built with locks. I certainly would not have wanted to purchase one, and you wouldn’t be 15,000-plus words into my three-part series about the UCs (that will probably go another 8,000 words before it’s finished) if the UCs had been lock-equipped.

So, please allow me to extend a very special THANK YOU to both Lipsey’s and Smith & Wesson, on behalf of RevolverGuys and Gals everywhere, for giving us these UC J-Frames without a lock. We sincerely appreciate it, and hope it represents the beginning of a new era for Smith & Wesson, where the lock begins to sunset across the catalog.

26.) The “black powder” reference goes back to Colt Single Action Army (SAA) frames. On the early SAA revolvers, which were designed prior to the introduction of smokeless powder, the base pin is retained with a screw that’s inserted from the front of the frame. Guns made with this design also featured a pronounced bevel on the leading edge of the cylinder.

A later redesign of the SAA changed the base pin retention system to a spring-loaded cross pin, and made the bevel on the leading edge of the cylinder less aggressive. These latter frames are often referred to as “smokeless powder frames,” even though the earliest frames with these features were made prior to the transition to smokeless powder, and would not have been warrantied by Colt for smokeless powder use.

credits

RevolverGuy would like to thank Smith & Wesson and UC Lead Product Engineer Andrew Foley for this excellent design, and for the information and images they provided in support of this article.

Another A+ paper. Waiting for Kevin’s thoughts and your Part 3 with all of the patience I can muster.

Thank you.

Thanks Tony! I’m wearing out my typing fingers, but will have that Part III on the way soon.

Sometimes I wonder if us “gun people” are resistant to new things. I think the .32 H&R Magnum was a good idea when it came out (although yes, I can understand the argument ‘Cops were moving away from revolver in the 80’s so a new cartridge was not relevant'”, and I think the .327 Federal Magnum is a good idea too. They accomplish what they were designed to do, but people would rather stick with the usual. Maybe a part of it is just cost and ease of acquisition (both are things I believe could be solved over time if more people bought into new cartridges, but I digress).

Now, I have no strong attachment to the .357 Magnum, but I do love the .38 Special. It is a very nice cartridge to shoot, and is plenty effective at self-defense with the right load. However, even someone like me who hasn’t been shooting nearly as long as most gun guys, much less shooting revolvers, was able to notice all those things you pointed out in this article. I never thought I’d say this, but I’m likely done with .38 Special in snubnosed revolvers. I’m prepared to throw my chips in with the .32 H&R and the .327 Federal. In the type(s) of revolver(s) I carry, these cartridges just make sense to me.

To further illustrate this article’s point, I’ll use my mother as a brief example. Due to age and health problems, she’s at a point now where she can only shoot with one particular hand. I bought her a Taurus Executive Grade last year thinking, “Yeah, a steel-framed .38 with a 3″ barrel, this should be good for her shootability-wise.” I’ve since come to realize that even that’s not ideal, and I understand why so many advocate .22s for elderly people. A .32 gives me options that .38 Special, sadly, cannot.

I like my Taurus 327, and I hope to acquire a S&W 632/432 UC in the future. I also hope that both the .32 H&R, as well as the .327, become more widely popular and available. And that manufacturers see this and start producing more firearms in .32 calibers. I, for one, think a S&W 617 equivalent revolver in .32 S&W Long would be a very sweet range gun.

Axel, I think people like your mom are definitely a large part of the audience the 432/632-UC was aimed at. On the other end of the Bell Curve are the highly proficient shooters who have the ability to maximize the potential of the .32 with proper bullet placement, and who will appreciate having six rounds instead of five.

Lest I leave the wrong impression, I think the .327 FM is an excellent cartridge. I just don’t like it in lightweight snubs, and would prefer to shoot it in larger, heavier guns. I feel the same about the original Magnum, in .357. Those are “big gun” loads for me, while the .38 Special (at least some of the loads) and .32 H&R qualify for “small gun” use.

Carrying a much lower recoiling .32 snubby that offers an extra round capacity than the standard .38 offering is hard to argue against, at least for me. But for a lot of people, the sticking points with the .32 revolvers are their ammo availability and cost, and whether the manufacturers will continue to make the stuff for very long.

Indeed. That’s one of the reasons why I never invested in .32 platforms. Hopefully the ammo supply will rise to meet the demand this time, and we’ll be in a new era for the .32. The last time the caliber could challenge the .38 for popularity was a century ago!

Really fascinating information! I am curious about something and maybe you are saving it for part III, but if the sights are regulated for the lighter ammunition offerings, is there any difference in the poa/poi of the heavier 158s in 38 spec.? I dont mean to brag but my local gunshop received 2 UC Js and is holding them for me to look at and decide which one I want. With the ample stock of 158gr ammo I have squirreled away, I intend to use what I have and not try to acquire several hundred rounds of lighter ammo. Thank you again for the time, effort, and experience you share with us.

Mark, yes there is going to be a shift in POI, but it wouldn’t be too dramatic at 15 yds and in—probably on the order of a couple inches. I didn’t shoot any 158 grain loads in the gun—heaviest I shot were the 148 grain wadcutters, which shot to the sights because of their lower velocity/energy.

If Part I was an appetizer, then Part II is a Technojunkie’s Dream !! Each increment gets better, and the anticipation for Part III is already simmering. This would make a great short movie !?!?!

So many folks still decry the two piece barrel system S&W (and even Ruger) use, but until they take the time to examine the engineering behind it, the reasons for it, and how it makes for a better end product, it remains something of an enigma. The early Dan Wesson revolvers showed how the two piece barrel and shroud could significantly up the accuracy game, and now S&W has taken it to the next level. Barrel clocking was always the Achilles heel in revolversmithing (and armorer reworking). The shoulder to frame torque had to be just right, and at the same time, the front sight had to be at top dead center. You had to have both or else everything was an exercise in futility.

For the cartridges: The .38 Special vs .32 H&R is a comparison of physics. For every action, there is that annoying equal and opposite reaction. We all like the action, but in lightweight snub revolvers, it’s that reaction (recoil) that gets in the way. Given revolvers of the same weight, pushing a 125-135 grain .38 Special is going to generate more recoil momentum than pushing an 85-100 grain .32 caliber projectile. The .32 is just going to be easier on the hands no matter how you do the math.

The felt recoil of the .38 Special in my steel J-Frames is stout enough, and even with target wadcutters it is still manageable to shoot passing qualification scores. In my Airweight M37-2 . . . not so much. Standard pressure loads get down right annoying after about 10-15 rounds – forget about 48 rounds. After five rounds of +P, I’m ready for an ice cold beer and Motrin.

Given the continuous evolution of more effective bullets, the projectiles topping the .32 H&R of today ares vastly superior to those topping .32 H&R of the 1980s. Notwithstanding my devotion to the .38 Special, and indulgences in the .357 Magnum, were I a budding shooter joining the Revolverguy culture, I would look seriously at the .32 H&R for my lightweight carry gun. I would surmise that as long as the ammunition companies keep the market fed, and reloaders happy, the cartridge and its many applications, particularly in lightweight snub guns, will thrive.

Thank you Sir! I’m glad to know I’m not the only one who reads the .38 snub recoil issue that way!

I think you’ll enjoy the expanded discussion on .32 ammo and ballistics that’s coming in Part III. I definitely think Jason lit a fire in the industry with these UCs, and we’ll see more .32 ammo choices heading our way soon. I had a very good conversation about that with friends at Federal during SHOT Show, and know they’re looking to improve their offerings in the caliber.

Another great article on a gun I wish nothing but success for, fingers crossed there are no QC issues because I want more innovation like this, I’ll be the first (and probably only) to want a 10 shot .32 akin to the S&W 327.

One interesting thing I saw recently online was “Byron’s Rubber Boot Grips” which had a neat cutout at the bottom which allows your pink to get full contact with the grip, there’s a YouTube video by “The Jason” showing it on his S&W 327 where I first saw it, quite a novel idea that I think should be on more boot grips.

Thanks Elliot, I’ll check them out!

Agreed on the QC. That will be the most difficult part of this project. There are always unexpected issues that crop up on a new gun, regardless of maker, as the workers get used to building it. I’m hoping the teething process will be fast on these guns, and S&W will hit their stride early. I know the folks involved in the UC project are keeping a close eye on things, and trying to be proactive.

Wow, where to begin? I imagine these are going to sell like hotcakes though the next decade! The six shot advantage, in my mind, comes down to dealing with two assailants who each get a pair… you still have one more for each if necessary. As far as the “green means go” sights, I too prefer orange- but it does make sense. Orange is only a spray can away, in any case. Sight height seems the least of all worries to me because people are, after all, vertical targets. If I aim high center chest and my rounds strike anywhere between, say, the jugular notch and the xyphoid process, I imagine they are good hits. But I’m not complaining about the sight regulation. The big thing I want to ask about is your mention of Comp 2 speedloaders. I have never seen such for a J frame! Where on earth could I find them? And as always, thank you, Mike, for an informative article.

Oops! I meant Comp I! Ya got me, brother! Great catch! Fixed.

Ah. Well, you got me excited for a moment.

Didn’t take much! 😆

Well done. Your index fingers must be tired, and not from shooting.

I’m through, not with .38 snubbies, but 5 shot .38 snubbies. I ran a pre-72 Colt Cobra as a backup on the job in preference to my tuned 642, and bought another in case that one went down. I still have one on my LEOSA ticket. If I can score a 432, more compact with less recoil and a non-stacking action, my Cobras will be put out to pasture.

P.S.: There’s a caliber-based mini debate on the LCR v. 432 on the Snub Noir site. With your permission I’ll direct them to footnote #4.

Glad you liked it, Lobo! Your older Colts are great guns, but parts are becoming scarce, and so are qualified people to work on them. A 432 UC would be a worthy replacement to extend the lives of your old Cobras.

I’m not a social media user, but feel free to send the Snub Noir crowd over here to read the piece. My best to them all.

I wonder how long the people who run their social media platform will allow the Noir crowd to operate on there? It’s becoming very uncomfortable for folks like all of us in cyberspace, these days.

I couldn’t agree more with the sights being regulated for the Speer Gold Dot load & wadcutters! My agency requires the use of the 135gr Speer in our backup revolvers, but at the range & at home I use a lot of wadcutters in my snubs.

I’ve been a huge fan of all types of .32’s for a while now, & am extremely excited to see these new Lipsey’s offerings. As the previous comment stated, now it’s time for a 8 or 10 shot L-frame .327 Fed Mag revolver. I’ve been dreaming about it for a while now; since there’s already a Model 69, I’d call it the Model 70 & make it out of stainless steel. It would be robust, very versatile, & have great capacity!

It’s good to hear from you again, pal! I hope you’ve been well since our last meeting. You’ll find the sights on these to be perfect for those two loads.

The UCs have encouraged all kinds of interest in the .32s again, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see a larger fun with more chambers down the road.

Be safe out there!

Another fantastic article Mike!

Thank you Sir! Much appreciated.

Thanks for more great info, Mike.

One question….

Will the .32 cal fit a regular j frame holster?

Thanks

Jim

Jim, the guns will fit many, probably most, J-Frame holsters, but some of the more tightly-boned holsters may be difficult, because the UCs have a different barrel and sight profile. The more traditional Centennial designs (i.e., the non-UC 642) have skinny one-piece barrels with thin ramp sights, and if your holster is tightly fitted in that area, it won’t fit the UCs with their two-piece barrel system and high profile sights.

If you can find a holster that’s advertised to fit the M&P 340, then it will be a great fit for the UCs, because they share the same two-piece barrel profile. Some of the more generic J-Frame fits, that aren’t tightly boned, will also be just fine.

Thank you, Mike, for the detailed look at the design innovation going on backstage. It’s encouraging to see technology contribute to making good designs better and stronger. Jason and Andrew teaming up and listening to experienced user’s wisdom guaranteed that good things would happen. That’s what we’re seeing here, and I’m glad you have been a part of it. Very cool.

Thanks Kevin. I’m excited to keep the ball rolling, and see more collaborations from these guys!

Very good articles and I have a question. Was there any serious considering for cutting these guns for use with moonclips? To me, the one thing that would really send these guns over the top would be if they were cut for use with moonclips. Thanks!

No Sir, that’s a custom feature that’s normally only found on Performance Center guns, and Lipsey’s was aiming to keep the cost on these down. Our friend Eli at TK Custom can cut your cylinder for moon clips if desired, though!

Excellent piece, and thank you. While I do not find .38 +p too harsh out of my Kimber, it is no lightweight. Thus I appreciate the comments about .32 H&R. A friend’s wife swears by it.

Also, it is good to educate folks on .22 mag out of a handgun. I love the caliber for varmint duty, out of a rifle, on our farm. It can, however, fail to ignite in a revolver, and the velocity is much lower than out of a long gun. Might not be an issue were my quarry a rabbit, but for two-legged trouble I would not want a click, especially from a semiautomatic pistol chambered in .22 mag.

Glad you enjoyed it, Wheelgunner! That “click” is the loudest sound in the world, isn’t it?

Excellent article, thanks! Lots of interesting technical details.

Looking forward to part three.

John

Thanks for the great reviews of the new Lipseys revolver. While I get the reasons for a 2-piece barrel design, my remaining concern is whether water can get in between the barrel and sleeve where I can’t get at it for cleaning. I mean, if it ain’t rainin’ you ain’t trainin’. How sealed up is that space?

Personally, I wouldn’t worry about it. The surfaces are tight where they meet, and I don’t think it’s likely you’ll get much, if any, moisture in there in normal conditions. If you’re trainin’ when it’s rainin’, any moisture that gets in there will cook off.

The real risk of exposure is from your sweat, during daily carry. I suppose it could get in there, but it’s stainless steel and aluminum, so it should be fairly resistant to corrosion, if it does.

The internals of the action are more accessible to moisture than the internal barrel sleeve, and we don’t usually worry about those rusting. Yes, you can get to those through the sideplate and clean/lubricate, but how many folks really crack open their guns to do that? I suppose if you were nervous about it, you could put an occasional drop of oil on the seams and let it soak, but I wouldn’t even worry about it.

Excellent article. Lots of good information. Any idea if/when they will come out with a Crimson Trace model?

Doc, I don’t believe that was considered, because it would increase the price and it was a goal to keep these affordable, and priced midway between the regular 642 and the more expensive Scandium guns.

In any case, it would be an easy aftermarket fix for the consumer. As popular as these special VZ Grips have become, you could probably take them off and sell them to finance the purchase of some CT laser grips, and not have to come up with very much out of your own pocket!

Mike,

That is an excellent idea! Thanks for getting back to me so quickly. I currently have a S&W 642-CT. If I bought an Ultimate Carry, do you think I would be able to switch the grips with my 642-CT?

Absolutely! The frames are the same size. You’re just a screwdriver away . . .

The VZ grips fit a little tight, so you’ll need to be careful removing them from the UC. A plastic credit card might be helpful to work them off without damaging them.

Outstanding article, as always. I’ll push back on .327 Fed Mag a little. I agree with everything you stated about releasing the UC in .32 H&R Mag, particularly on keeping cost reasonable. Your anecdotes on new shooters (or those that won’t commit much time to training) favoring a .32 has rung true for me several times; I’ll offer up a whole shooting bench of handguns for them to try, and the simplicity, low recoil, and pleasant level of muzzle blast has led several to picking the LCR in .327 FM as their favorite. They can handle .32 H&R Mag loads just fine, and practicing with S&W Long ammo is quite pleasant.

For my own selfish reasons, I’d also lobby hard for a scandium version in .327 FM. My EDC is a 340PD, preceded by an LCR in .327 FM. In the LCR I carried Underwood 95gr XD and found the recoil of that lightweight bullet to be less than the heavier FM loads, such as Gold Dot. Muzzle blast and noise were still fierce, but that’s a feature. The extreme lightweight of the scandium S&W guns, shaving off a few oz in my pocket, won me over. I gave up that 6th cartridge for comfortable carry. I’d gladly pay whatever S&W charges for a scandium 6rd J-frame in .327 FM (with all the UC features) to gain 6rd capacity and the flexibility to chamber several excellent cartridges. Even if I chose to carry .32 H&R Mag loads, knowing I can stock/buy/chamber .327 FM ammo is a great bonus when prices jump and availability wanes.

It’s like having a 5.56×45 or .223 Wylde chamber combined with a 1:7” or 1:8” twist in an AR; I’d rather have the flexibility to shoot any pressure or bullet weight available, even if I usually practice with .223 Rem and 55gr FMJ. Same reason I don’t own a single .38 Special firearm, but own many .357 Mag firearms.

Anner, that’s an entirely fair argument, particularly with all the supply chain issues we’ve seen over the past four years, and all the ammo panics since Y2K. Having that flexibility to shoot a variety of cartridges could be very important to some users.

I don’t think it’s likely you’ll see a Lipsey’s exclusive UC in Scandium, but with the spike in interest in the .32, it’s not beyond possibility that S&W could chamber a Scandium M&P for the .327 FM.

If they released a scandium M&P in 327 I’d be all over that. And the various 327 models other folks mentioned above: steel 7-10rd variants. A K-frame 7- or 8-shooter would be a fantastic trail gun.

Well, my local dealer called me with the first 422UC they got in. I brought it home.

I have a decades old 422 with boot grips. I compare this to the 422UC.

Initial evaluation:

1. sights: 422UC sights are the best I have ever seen on a J frame.